Fatigue is common among patients presenting to physicians. Fatigue can lead to serious public health consequences and may be caused by a vast array of etiologies. This article reviews the assessment of fatigue from the physical medicine and rehabilitation physician’s perspective. The importance of a history and physical examination is emphasized, complemented by the use of laboratory studies. Rating scales used to assess fatigue from different etiologies are discussed, and patient-friendly Internet resources about fatigue are included.

Clinical fatigue has been described to include 3 major features: (1) generalized weakness, causing an inability to begin certain activities, (2) easy fatigability and decreased ability to maintain performance, and (3) mental fatigue, resulting in memory loss, impaired concentration, and emotional lability. Based on the duration of symptoms, fatigue can be categorized into 3 categories: (1) recent fatigue—symptoms lasting less than 1 month, (2) prolonged fatigue—symptoms lasting more than 1 month, and (3) chronic fatigue—symptoms lasting greater than 6 months but not automatically implying chronic fatigue syndrome.

Patients with a chief complaint of fatigue are frequently encountered by physicians across the world. In a postal survey of 6 general practices in southern England, 18.3% of respondents reported substantial fatigue lasting 6 months or longer. In a rural family medicine clinic in Israel, almost 32% of adult patients reported symptoms of fatigue or its equivalent terms at least once during a 10-year period. In a representative study of adults in the United States, 14.3% of male respondents and 20.4% of female respondents reported suffering from fatigue. Studies from Canada and France have reported similar findings.

Fatigue can produce serious public health consequences. In a study of the elderly from Norway, physical fatigue represented a possible risk factor for falls. In a US study estimating fatigue prevalence and associated health-related lost productive time (LPT), workers with fatigue annually cost employers $136.4 billion in health-related LPT, representing an excess of $101.0 billion compared with workers without fatigue. Fatigue represents anywhere from 7 to 10 million office visits to physicians per year.

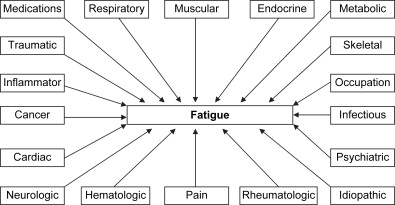

Fatigue has a variety of etiologies ( Fig. 1 ). In a prospective cohort study of members of a health maintenance organization, medical or psychiatric disorders accounted for 66% of patients who reported chronic fatigue. In a series of 217 patients presenting with a complaint of fatigue, 35% had endocrine, cardiovascular, respiratory, or hematologic causes, and 65% had psychiatric causes. In a retrospective chart review of 176 patients with a diagnosis of fatigue during a 12-month period, 39% were caused by physical causes, 41% were caused by psychological causes, and 12% were caused by mixed causes.

Fatigue is commonly associated with both physical illness and psychiatric disorders. Careful clinical assessment is required to determine the presence of any underlying disorder(s) that may lead to fatigue, although the cause may not always be identified. In a study of final diagnoses in patients presenting to Dutch family physicians, a specific diagnosis was not identified in 37.5% of patients who presented with general weakness or tiredness.

The goal of this review article is to discuss how the physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R) physician might assess fatigue in an adult patient with disabilities.

Assessment of fatigue

The clinical assessment of fatigue begins before the patient even enters the physician’s office. Simply observing and talking to the patient while going from the waiting room to the office may reveal a wealth of information. Does she independently get up from a chair? Is he using crutches? Is her speech dysarthric? Is his affect flat? Does she become short of breath? Is he lethargic? Is she using a wheelchair? Does he cough? Does she have a cast? Does he fall? Early attention to such details starts the process of formulating a differential diagnosis, long before any complex physical examination, expensive laboratory studies, or lengthy rating scales.

Obtaining a thorough history of the fatigue from the patient is important, as the medical history sets the tone for the remainder of the assessment. Important information includes date of onset, duration, frequency, aggravating factors, relieving factors, and associated symptoms. It is also important to ask about the impact of fatigue on activities of daily living such as ambulation, transfers from different surfaces, dressing, bathing, meal preparation, work, and hobbies.

As often as possible, the patient’s own words should be documented in the medical record using quotes. Collateral information from a family member or other caregiver is especially critical when a patient is cognitively impaired. Documenting items such as a review of systems, current prescribed medications ( Box 1 ), over-the-counter medications, medical illnesses, surgical history, trauma history, psychiatric history, substance use history, family history, occupational history, and living environment can help paint a well-rounded clinical picture of the patient. A review of any prior medical records can provide additional collateral information.

Beta blockers

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

Sedative-hypnotics

Antipsychotics

Antidepressants

Anticonvulsants

Antispasticity drugs

Chemotherapeutic drugs

Interferon

Anesthetics

Analgesics

Many unidimensional and multidimensional rating scales are available for the assessment of fatigue, which may be valuable in further characterization of the fatigue ( Box 2 ). A particular rating scale must be carefully chosen based on multiple factors, such as what aspects of fatigue are to be assessed and the specific patient population in which the scale has been validated.

Fatigue Severity Scale

Visual Analog Scale for Fatigue

Barrow Neurologic Institute Fatigue Scale

Cause of Fatigue Questionnaire

Fatigue Impact Scale

Barroso Fatigue Scale

Fatigue Descriptive Scale

Myasthenia Gravis Fatigue Scale

Task-Induced Fatigue Scale

Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire

Fatigue Assessment Instrument

Brief Mental Fatigue Questionnaire

Rhoten Fatigue Scale

Fatigue Symptom Inventory

FibroFatigue Scale

Dutch Exertion Fatigue Scale

Revised-Piper Fatigue Scale

Schwartz Cancer Fatigue Scale

The physical examination begins with measuring vital signs. Is she tachypneic? Does he have a fever? Is she hypotensive? What is his pain rating? Before using any elaborate instruments, gross observations with the naked eye should be made. How is her gait? Are his lips blue? Does she have all limbs? Are his eyes yellow? In an orderly manner, each organ system should be evaluated, noting pertinent positive and negative findings. A thorough neurologic and orthopedic examination is very important as is a functional assessment of the patient’s ability to rise from the seated position and ambulate. Special note should be made of the amount of assistance that the patient requires for these activities.

Based on the information obtained thus far, a reasonable differential diagnosis for fatigue can be formulated at this juncture. Appropriate laboratory studies should be ordered only after obtaining a detailed history and physical examination. There is no “routine” laboratory workup for fatigue, as each patient’s history, physical examination, and differential diagnosis are unique. Laboratory studies ought to be viewed as complementary to—not substituting for—a comprehensive history and physical examination.

Etiologies of fatigue

Although each category is discussed separately, the PM&R physician must remember that in a given patient, fatigue may be explained by more than 1 etiology at a certain point in time. Furthermore, just because 1 etiology is found, it does not mean that the search for other contributing etiologies should be halted. Each category includes a discussion of clinical disorders that may present with fatigue and common methods used to diagnose fatigue in the presence of these disorders.

Iatrogenic

A thorough review of all prescribed medications by all physicians from whom the patient is seeking care is warranted at every visit. Many medications, especially when first administered, may cause fatigue ( Table 1 ). These include, but are not limited to, beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, sedative-hypnotics, antipsychotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, antispasticity drugs, chemotherapeutic drugs, interferon, anesthetics, or analgesics. The continued medical indication for each medication should be analyzed at every appointment. If medically feasible, an effort should be made to discontinue or minimize the number of such medications contributing to fatigue.

| National Library of Medicine/National Institutes of Health | http://www.nlm.nih.gov/MEDLINEPLUS/ency/article/003088.htm |

| National Cancer Institute | http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/fatigue/Patient |

| American Cancer Society | http://www.cancer.org/docroot/MIT/MIT_2_2x_Fatigue.asp |

| Muscular Dystrophy Association | http://www.mda.org/publications/Quest/q121fatigue.html |

| Mayo Clinic | http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/fatigue/HQ00673 |

| University of Maryland | http://www.umm.edu/ency/article/003088.htm |

| University of Texas | http://www.mdanderson.org/topics/fatigue/ |

| AIDS InfoNet—University of New Mexico | http://www.aidsinfonet.org/fact_sheets/view/551 |

| eMedicine Health | http://www.emedicinehealth.com/fatigue/article_em.htm |

Traumatic

Fatigue is common in patients with spinal cord injury and traumatic brain injury (TBI). Prevalence of fatigue ranges from 50% to 80% in patients with TBI living in the community. Etiologies of trauma include, but are not limited to, motor vehicle accidents, violence, or falls. Imaging studies, such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or x-ray, may be helpful in the diagnosis of traumatic disorders. One scale used to assess fatigue in the presence of TBI is the Barroso Fatigue Scale, which was created from 5 other fatigue scales: Multidimensional Assessment for Fatigue, Fatigue Severity Scale, Fatigue Assessment Instrument, Fatigue Impact Scale, and General Fatigue Scale. The Fatigue Severity Scale has been used to assess fatigue in patients with spinal cord injury.

Inflammatory

Inflammatory etiologies of fatigue include, but are not limited to, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. Laboratory studies, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibody, or rheumatoid factor, may be helpful in the diagnosis of inflammatory disorders. A working group and expert panel on SLE has recommended the 9-item Fatigue Severity Scale for the assessment of fatigue in patients with SLE. The Multidimensional Assessment for Fatigue Scale has been used to assess fatigue in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Neurologic

Neurologic etiologies of fatigue include, but are not limited to, multiple sclerosis (MS), stroke, motor neuron disease, or myasthenia gravis. Cranial nerve, sensory, reflex, strength, or focal abnormalities may be uncovered with a thorough neurologic examination. Laboratory studies, such as head CT, head MRI, electromyography, cerebrospinal spinal fluid analysis, or the Tensilon test, may be helpful in the diagnosis of neurologic disorders. Scales such as the Fatigue Severity Scale, the Fatigue Impact Scale, the Fatigue Descriptive Scale, and the Task Induced Fatigue Scale have been used in the assessment of MS-related fatigue. The Fatigue Impact Scale and the Checklist Individual Strength (fatigue subscale) have been used in the assessment of post-stroke fatigue. The Myasthenia Gravis Fatigue Scale has been used in the assessment of myasthenia gravis-related fatigue.

Psychiatric

Depressive disorders such as major depressive disorder can lead to fatigue. A major depressive episode is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), as a 2-week period of 5 or more of the following symptoms: depressed mood, diminished interest in activities, weight loss, sleep changes, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness, psychomotor agitation/retardation, poor concentration, and recurrent thoughts of death. The symptoms must cause significant impairment in important areas of functioning and not be due to the direct physiologic effects or a substance or a general medical condition. On mental status examination, assessment of appearance, behavior, mood, affect, and safety can be helpful in making a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, the Beck Depression Inventory-II, and the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale can be used to assess fatigue in patients with major depressive disorder.

Anxiety disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), can lead to fatigue. DSM-IV-TR criteria for GAD include excessive anxiety and worry about a number of events or activities, difficulty controlling the worry, restlessness, being easily fatigued, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance. The symptoms must cause significant impairment in important areas of functioning and not be due to the direct physiologic effects or a substance or a general medical condition. On mental status examination, assessment of appearance, psychomotor abnormalities, mood, and affect can be helpful in making a diagnosis of GAD. The Worry and Anxiety Questionnaire is based on DSM criteria for GAD and includes questions about the associated somatic symptoms of GAD.

When fatigue is present, substance use disorders should be considered. Patients with chronic fatigue and a lifetime history of a substance use disorder have been reported to have more lifetime symptoms of depression and are more likely to have a history of suicidal ideations or attempts. DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance abuse include recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations, use in physically hazardous situations, substance-related legal problems, or use despite persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance dependence include tolerance, withdrawal, using in larger amounts or longer than intended, unsuccessful efforts to cut down use, great deal of time spent in activities needed to obtain the substance, important activities given up or reduced due to substance use, or use despite knowledge of having a physical or psychological problem likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. Laboratory studies, such as a urine toxicology screen, can be helpful in detecting use of cocaine, amphetamines, cannabis, opiates, and benzodiazepines. Alcohol use disorders can be screened with questionnaires such as the CAGE questionnaire, the Michigan Alcohol Screening Test, and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Laboratory studies, such as liver function tests (aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase), mean corpuscular volume, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, and carbohydrate-deficient transferrin, can also be helpful in detecting alcohol use disorders.

Neuromuscular

Neuromuscular disorders such as facioscapulohumeral dystrophy, myotonic dystrophy, or hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy can lead to fatigue. Patients may complain of weakness of muscles, stiffness, cognitive problems, cold feet, muscle pain, dysphagia, respiratory insufficiency, or loss of balance. Physical examination may reveal muscle wasting, ptosis, weakness in various muscles of the body, foot deformities, foot drop, sensory abnormalities, or reflex abnormalities. Laboratory studies, such as creatine kinase levels, genetic testing, muscle biopsy, nerve biopsy, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, or a nerve conduction study, may be helpful in the diagnosis of neuromuscular disorders. The Checklist Individual Strength scale has been used in the assessment of fatigue in patients with neuromuscular disorders.

Pain

Pain disorders such as fibromyalgia can lead to fatigue. Symptoms may include widespread pain, muscle aches, muscle spasms, sleep disturbances, allodynia, or headaches. Findings on physical examination include tenderness in 11 of 18 point sites on digital palpation. The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire, the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory, and the FibroFatigue Scale have been used to assess fatigue in patients with fibromyalgia.

Respiratory

Fatigue may be caused by respiratory disorders such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, or sarcoidosis. A detailed physical examination may yield abnormal signs such as wheezing, red bumps on the skin, or swollen lymph nodes. Laboratory studies, such as a chest x-ray, chest CT, pulmonary function tests, bronchoscopy, or polysomnography, may be helpful in the diagnosis of respiratory disorders. The Fatigue Assessment Scale has been used in the assessment of sarcoidosis-related fatigue. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory has been used to assess fatigue in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and the Chronic Respiratory Disease questionnaire contains items assessing fatigue. The Fatigue Severity Scale has been used in the assessment of fatigue related to sleep disorders.

Cancer

Fatigue in patients with cancer may be related to multiple factors, including the underlying neoplasm itself, antineoplastic treatments, coexisting systemic diseases, electrolyte abnormalities, endocrine abnormalities, chronic pain, deconditioning, sleep disorders, depression, or anxiety. Findings on history and physical examination such as cachexia, night sweats, unusual lumps, or hemoptysis may raise suspicion for an underlying neoplastic process. Laboratory studies, such as a complete blood cell count, CT, MRI, or a biopsy, may expose a cancer. Scales that have been used to assess cancer-related fatigue include the Fatigue Assessment Questionnaire, Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory, Fatigue Symptom Inventory, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (Fatigue subscale), Linear Analog Fatigue Scale, Revised-Piper Fatigue Scale, Rhoten Fatigue Scale, Pearson-Byars Fatigue Feeling Checklist, Visual Analog Fatigue Scale, Cancer Fatigue Scale, and Revised Schwartz Cancer Fatigue Scale.

Infectious

Infectious etiologies of fatigue include, but are not limited to, influenza, infectious mononucleosis, pneumonia, Lyme disease, Human immunodeficiency virus, or parasitic diseases. Manifestations of an infectious process may consist of fever, chills, cough, headache, malaise, or headache. A physical examination may discover rales, lymphadenopathy, rash, or sore throat. Laboratory studies, such as a complete blood cell count, monospot test, chest x-ray, urinalysis, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, viral titer, stool culture, or blood culture, may be helpful in diagnosing an infectious disorder. The Daily Fatigue Impact Scale has been used to assess fatigue in patients with an influenza-like illness. The Fatigue Assessment Instrument has been used to assess fatigue in patients with Lyme disease and post-Lyme chronic fatigue.

Hepatic

Hepatic etiologies of fatigue include, but are not limited to, primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, or hepatitis C. Treatments for hepatitis such as interferon may also lead to fatigue. Symptoms of hepatic disease include loss of appetite, dark urine, or abdominal discomfort. Jaundice, hepatomegaly, or splenomegaly may be found on physical examination. Laboratory studies, such as liver function tests, viral antigens/antibodies, antimitochondrial antibodies, abdominal ultrasound, or abdominal CT, may be helpful in the diagnosis of hepatic disorders. The Fatigue Impact Scale has been used to assess fatigue in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. The Multidimensional Assessment of Fatigue Scale has been used to assess fatigue in patients with hepatitis C.

Renal

Factors that may lead to fatigue in patients with renal disorders such as end-stage renal disease include prescribed medications, abnormal urea and hemoglobin values, sleep disorders, and psychological factors such as depression. The Fatigue Severity Scale, the Short-Form Health Survey vitality subscale, and the Revised-Piper Fatigue Scale have been used to assess fatigue in patients with end-stage renal disease.

Endocrine

Endocrine causes of fatigue may include hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, pituitary insufficiency, or adrenal insufficiency. Symptoms of endocrine disorders may include weight loss, loss of appetite, depression, muscle cramps, cold intolerance, polyuria, polydipsia, or polyphagia. Laboratory studies, such as electrolytes, thyroid-stimulating hormone, fasting blood glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin, serum cortisol, or serum aldosterone, may be helpful in the diagnosis of endocrine disorders. The Fatigue Questionnaire has been used to assess fatigue in patients with Addison’s disease.

Cardiovascular

Cardiovascular etiologies of fatigue include, but are not limited to, congestive heart failure and pulmonary hypertension. Symptoms may include dyspnea on exertion, dyspnea at rest, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, or exercise intolerance. Edema, hepatomegaly, rales, heart murmurs, or cyanosis may be found on physical examination. Laboratory studies, such as echocardiography, chest x-ray, or electrocardiography, may be helpful in the diagnosis of cardiovascular disorders. The Fatigue Assessment Scale and the Dutch Exertion Fatigue Scale have been used to assess fatigue in patients with heart failure.

Others

Fatigue may result from a wide variety of other etiologies, such as hematologic disorders (eg, severe anemia), metabolic disorders (eg, hypercalcemia), excessive physical activity, insomnia, jet lag, and somatization disorder. A careful history, a thorough physical examination, and pertinent laboratory studies will help clarify which etiology or etiologies may be contributing to a patient’s fatigue.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree