While symptoms and impairment may continue to affect the lives of individuals such as Sam, perceptions of one’s quality of life may alter over time. Indeed, improvement in quality of life is frequently considered the ultimate goal of rehabilitation services for individuals with severe and persistent mental illness (Oliver et al., 1996). However, traditional measures of outcome for those with severe mental illness have generally relied on the assessment of symptoms and impairment. While these indicators are important, they tend to be limited and fail to consider broader quality of life issues such as accommodation, finances, employment, physical health, leisure, social relations, etc. It is now clear that any assessment of people with psychiatric disability needs to consider quality of life and satisfaction (in addition to symptoms and functioning).

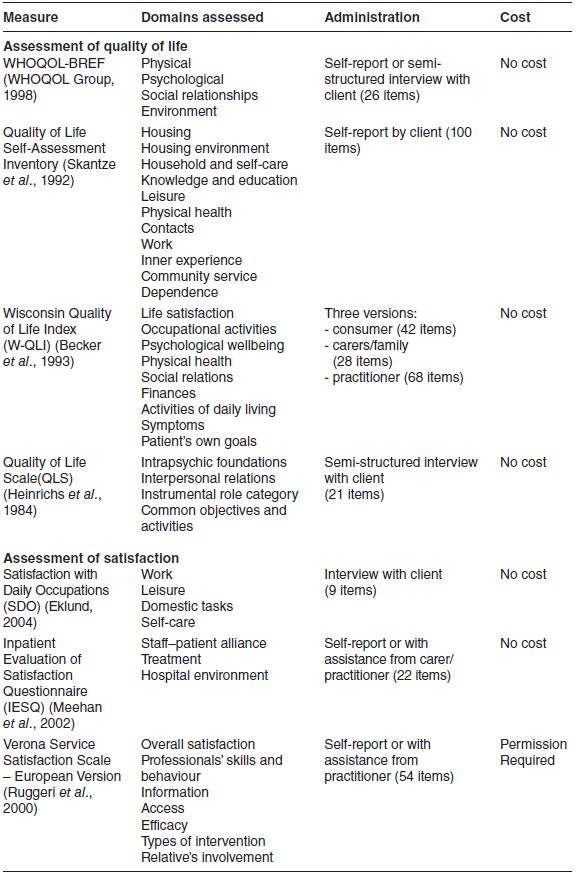

There is lack of agreement, however, on what factors should be considered when assessing quality of life in the mental health field. Nonetheless, it is generally accepted that quality of life is multidimensional and measures should include some assessment of the domains described above. Moreover, it is also clear that assessment of quality of life should include an objective component (such as the amount of money one has to spend) and a subjective component (i.e. how the individual feels about the amount of money they have to spend). In this chapter, we focus on quality of life measures that meet the criteria discussed above. Moreover, the selected measures have been found to be useful in clients with severe mental illness (e.g. Wisconsin Quality of Life Index and the Quality of Life Self-Assessment Inventory) and in those displaying deficit syndrome (e.g. Quality of Life Scale) (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 Summary of measures.

Client satisfaction with the services received is also becoming increasingly important. Satisfaction has been found to be important in influencing other client outcomes in that more satisfied clients demonstrate better outcomes (Ruggeri, 1994). Methods of assessing satisfaction have steadily improved over the past 20 years and there is now a range of measures available for assessing satisfaction in different health care settings, including mental health. The measures discussed in this chapter can be administered by interview (Satisfaction with Daily Occupations) or through self-report (Inpatient Evaluation of Satisfaction Questionnaire and Verona Service Satisfaction Scale). Moreover, they are brief, easy to score and have adequate psychometric properties (see Table 5.1).

While other quality of life and satisfaction measures are available, these tend to be too long and cumbersome for use in individuals with severe mental illness.

Quality of life

As outlined earlier, improving one’s quality of life is an important component of rehabilitation efforts. For many individuals with severe disability, return to full functioning may not be possible. However, being able to live a full and satisfying life within the limitations of one’s disabilities may be a realistic goal for many. Below, we discuss four quality of life measures that could be considered for use in clients with severe and persistent mental illness.

World Health Organization Quality of Life (Brief Version)

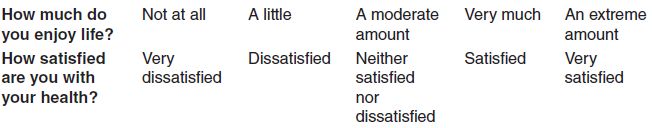

The original version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) measure was developed by a multinational group seeking a measure that would capture cultural issues in addition to the usual quality of life domains (WHOQOL Group, 1998). The original version of the measure contains 100 statements/items and assesses six quality of life domains (physical health, psychological health, level of independence, social relationships, environment and spirituality). More recently, a brief version of the measure (WHOQOL-BREF) containing 26 items has emerged (Skevington et al., 2004). The 26-item version provides assessment of four domains (physical, psychological, social and environmental). Items are rated on the degree to which one experiences a number of given activities and satisfaction with aspects of life (Box 5.1).

The WHOQOL-BREF can be completed through self-report (5 minutes) or practitioner interview (15–20 minutes). While the instrument is easy to understand and complete, the scoring is somewhat complicated in that three items (Q3, Q4, Q26) are reverse scored prior to calculation of domain scores and total score. Raw scores are then transformed to a scale of 0–100. The manual that accompanies the measure will assist practitioners in this task.

The University of Bath is the WHO distributor for the UK version. Users must register to use the measure and this can be done online at: www.bath.ac.uk/whoqol/questionnaire/info.cfm. Copies of all WHOQOL measures are also available from the site at no cost.

Wisconsin Quality of Life Index

The Wisconsin Quality of Life Index (W-QLI) was developed in the US by Becker and colleagues (1993). The measure differs from others in the mental health field in that it was developed for use in those with severe and persistent mental illness (Becker et al., 1993). The measure is one of the most comprehensive available since it covers nine quality of life domains and provides ratings from three key players: the client, his/her carer and his/her service provider. The W-QLI scores range from -3 (the worst things could be) to +3 (the best things could be). A score of 0 on the W-QLI is a middle-range score which is close to the average or normative value for the target population. Each domain is scored separately using a combination of satisfaction and importance scores (Box 5.2). When W-QLI scores are computer scored, a one-page report is produced documenting the score for each domain. Client goals for improvement with treatment are presented verbatim, allowing the clients and service providers to discuss discrepancies and come to agreement on goals to be pursued.

The W-QLI is an easy-to-use self-report or practitioner-administered instrument used to assess and monitor quality of life in individuals with severe mental illness. It is designed to document client goals for improvement with treatment and to aid clients and staff in their work together to achieve desired goals and improved quality of life for clients. The developers of the measure (Becker et al., 1993) report that through use of the measure:

- clients and providers will increase their understanding of the current client quality of life status

- clients will take a more active role in their treatment

- communication between clients and providers will be improved

- the practitioner’s role as client educator will be enhanced

- clients will increase their quality of life and goal achievement, leading to increased empowerment.

Very dissatisfied

Very dissatisfied  Moderately dissatisfied

Moderately dissatisfied  A little dissatisfied

A little dissatisfied Neither satisfied or dissatisfied

Neither satisfied or dissatisfied A little satisfied

A little satisfied  Moderately satisfied

Moderately satisfied  Very satisfied

Very satisfied Not at all important

Not at all important  Slightly important

Slightly important  Moderately important

Moderately important Very important

Very important  Extremely important

Extremely importantThe measure also has the advantage of capturing multiple views of a client’s quality of life (client, provider and carer). Differences between the ratings indicate the need for discussion with the different parties to identify the reason for such differences. This provides an opportunity to enhance the working alliance between clients and providers/carers. The psychometric properties of the measure are adequate (Diaz et al., 1999; Sainfort et al., 1996).

Notwithstanding the above advantages, the measure is relatively long (takes about 25 minutes to complete the client version) and it has a variety of response options (as outlined in the sample item in Box 5.2. As such, it would prove difficult to apply the measure via telephone interview. Moreover, it is more difficult to score than the other measures reviewed. However, a computer program is available to assist with scoring.

General information about the W-QLI is provided at the W-QLI website at http://wqli.fmhi.usf.edu. Copies of the measure and the scoring manual are available free of cost. However, the user needs to sign a copyright agreement and provide deidentified data to Professor Becker for ongoing testing of the measure. Email address for Professor Becker is: becker@fmhi.usf.edu.

Quality of Life Self-Assessment Inventory

The Quality of Life Self-Assessment Inventory (QLS-100) was developed in the UK by Skantze and colleagues (1992). It contains 100 factors which are organised under 11 quality of life domains. For example, the ‘Housing’ domain contains the following factors: size, lighting, heating, hot water, drinking water, kitchen, toilet, bath/shower, appearance, peace and privacy. To complete the measure, individuals simply circle those aspects/factors which are considered unsatisfactory in their life (Box 5.3). The number of factors circled is subtracted from the total number (i.e. 100) to provide a scale score. A lower score indicates that more items have been circled and this implies that the individual has more factors requiring attention and, as such, a lower quality of life. A 7-day test-retest reliability for the measure total score was high with a correlation coefficient of r = 0.88.

This measure is one of the easiest to complete and one of the least difficult to score. Items identified by clients as being unsatisfactory can become the focus of further discussion with the individuals involved. In the example provided in Box 5.3, ‘clothing’ has been circled/identified as being unsatisfactory by the client. Further questioning of the client is required to identify what aspects of his/her clothing are considered unsatisfactory and what interventions are required to address this.