CHAPTER 4 Arthroscopic Treatment of Radial-Sided TFCC Lesions

Functional Anatomy of TFCC

The triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) is a ligamentous structure composed of fibrocartilage located between the distal ulna and the ulnar carpus.1,2 The TFCC has several functions, the most important of which is to stabilize the ulnar carpus.3 The TFCC also provides a continuous gliding surface across the distal face of the radius and ulna for flexion-extension and translational movements. It provides a flexible mechanism for stable rotational movements of the radiocarpal unit around the ulnar axis, and cushions the forces transmitted through the ulnocarpal axis.4 The TFCC improves functional stability of the wrist while allowing 6 degrees of motion: flexion, extension, supination, pronation, and radial and ulnar deviation. The TFCC functionally enhances the surface area of joint contact between the radius and ulna to the carpus.

The TFCC consists of several discrete anatomical structures that when combined form a functional unit.2 The dorsal and volar radioulnar ligaments encase the articular disc and create the distal radioulnar joint. The ulnar collateral ligament, the meniscal homologue, the tendon sheath of the extensor carpi ulnaris, and the ulnocarpal ligaments intimately attach to the articular disc. This broadly based disc adheres to the radial sigmoid notch and extends to the ulnar styloid.

The TFCC transmits axial load from the wrist to the forearm in a longitudinal direction across the ulnar column of the wrist.3 Force is transmitted across the ulnar aspect of the lunate, the triquetrum, and the TFCC on the distal radioulnar joint. The bony morphology of these structures reflects an adaptation to the unique demands on this part of the wrist. Densitometric studies have demonstrated patterns of enhanced subcortical mineralization in the bones of the ulnar wrist. The patterns of increased mineralization correspond to the distribution of force in a longitudinal direction across the ulnar column of the wrist.5

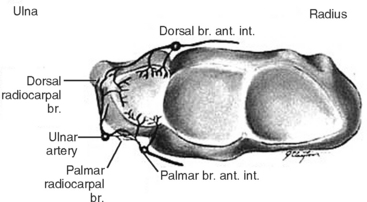

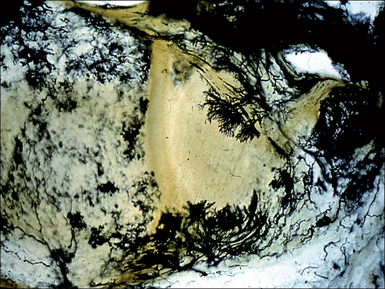

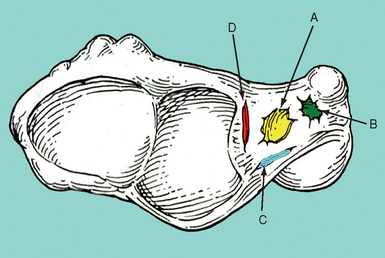

The vascular anatomy of the TFCC is variable, and is in part responsible for the differences in outcomes resulting from different patterns of injuries. Perfusion to the TFCC arises from dorsal and palmar branches of the anterior interosseus artery. Dorsal and palmar branches of the ulnar artery supply the ulnar styloid and the ulnar aspect of the volar periphery (Figure 4.1).6,7 Studies of the vascular anatomy of the TFCC have demonstrated that vessels supply the TFCC from the palmar, ulnar, and dorsal attachments of the joint capsule in a radial fashion—and that the blood flow penetrates less than 20% of the periphery (Figure 4.2).6,8,9 The central portion of the TFCC is therefore relatively avascular. Although the radial aspect of the disc is hypovascular compared to the ulnar side, some radial-sided vascularity has been documented in cadaveric studies—suggesting that healing is possible in this region.9

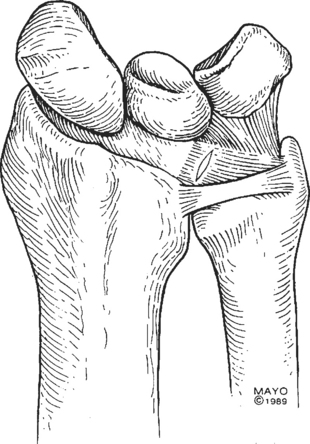

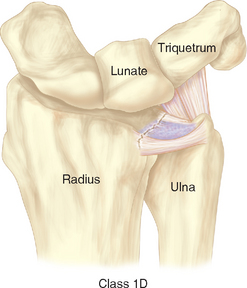

The radial insertion of the TFCC is vulnerable to injury when axial load is combined with pronation and ulnar deviation or extension of the wrist. This motion exposes the TFCC to shear stress, which if substantial enough causes distortion of the TFCC. Extreme stress loads can result in a TFCC tear and subsequent degeneration of the TFCC from its radial insertion (Figures 4.3 and 4.4).10

Patterns of TFCC Injury

The TFCC transmits force from the wrist to the forearm, and injuries to the TFCC are a common cause of ulnar-sided wrist pain. When evaluating TFCC injuries, it is important to distinguish between age-related (degenerative) and traumatic etiologies. A useful classification system for TFCC injuries was established by Palmer (Figure 4.5 and Table 4.1).11

Table 4.1 Palmer’s Classification of TFCC Lesions (Acute and Degenerative)

| Class 1: Traumatic |

| Class 2: Degenerative (Ulnar Impaction Syndrome) |

Classification from Palmer AK. Triangular fibrocartilage complex lesions: A classification. J Hand Surg [Am] 1989;14:594–606.

Age-related nontraumatic lesions to the TFCC are typically characterized by central perforations.8,12 In a study of 180 wrist joints in 100 cadavers ranging in age from fetuses to 94 years, Mikic demonstrated that degeneration of the TFCC begins in the third decade of life. He showed that this degeneration increases in frequency and severity as people age. After the fifth decade of life, he noted 100% of TFCCs to be abnormal appearing. It is important to note, however, that these age-related TFCC lesions are often asymptomatic.13

Evaluation of Radial-Sided TFCC Injuries

Patients with radial-sided TFCC injuries typically present with ulnar-sided wrist pain and clicking.14–16 Frequently, a history of a fall onto a pronated and hyperextended wrist can be elicited. Class 1D injuries are frequently associated with distal radius fractures.17 Upon clinical examination, the examiner may note crepitus of the DRUJ during active supination and ulnar deviation. The patient may experience pain in the region of the DRUJ, with dorsopalmar translation of the distal ulna. As a provocative test, the examiner can fix the patient’s wrist in ulnar deviation while rotating the forearm between pronation and supination. A click may indicate a tear of the TFCC, which is interposed between the carpus and the ulnar head. If the injury is advanced, and osteoarthritis has caused deterioration of the sigmoid notch, the patient may experience pain when lateral force is applied to the ulna (compressing it into the radius). The stability of the DRUJ should also be assessed.

Numerous modalities are useful in evaluating the location of injury within the TFCC. Triple-injection wrist arthrography is particularly valuable in detecting Palmer class 1D lesions.18,19 With this procedure, 5 to 10 ml of contrast agent is injected into the ulnar aspect of the wrist, tangent to the triquetrum, under continuous radiographic visualization. This allows examination of the distribution and flow of contrast through the wrist (Figure 4.6).

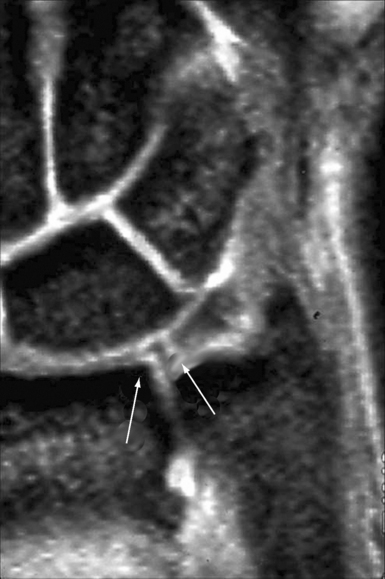

MRI has become the most widely utilized imaging modality for the evaluation of TFCC injuries.20,21 Using dedicated small-joint wrist coils, MRI predicts lesions of the TFCC with approximately 80% sensitivity and 70% specificity.22 Fat suppression T2-weighted images in the coronal plane can best elucidate the precise anatomical details of the TFCC. MRI has the capacity to localize lesions to the central part of the disc, the periphery, and the radial insertion (Figure 4.7). This specificity can aid in the surgical planning for the treatment of such lesions.

FIGURE 4.7 MRI of the wrist. A T2-weighted coronal image shows a tear at the radial attachment of the TFCC.

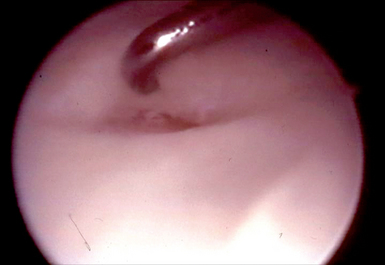

Wrist arthroscopy has recently become the criterion standard for both diagnosing and treating lesions of the TFCC. When compared to MRI and arthrography, arthroscopy most accurately determines the location of lesions and the size of tears. It also allows determination of whether a flap is unstable.23,24 Scar and vascular invasion along the periphery of the TFCC, as well as tears within the lunotriquetral interosseous ligament or ECU subsheath, indicates injury. Specifically, a trampoline test is positive when the surgeon’s probe fails to bounce off the TFCC, indicating laxity of the disc and the presence of a tear (Figure 4.8).25 It is important to note, however, that laxity of the TFCC does not necessarily translate into instability of the DRUJ.26

Surgical Treatment of Radial-Sided TFCC Lesions

The anatomy and patterns of injury to the TFCC are well elucidated. Efforts now focus on the optimal treatment of different types of lesions. With recent advances in small-joint arthroscopy, arthroscopic debridement and repair of TFCC lesions are now possible. Historically, treatment of most tears of the TFCC (particularly those involving the avascular horizontal disc) emphasized debridement or excision.14,27,28 This practice stemmed from two important principles. First, the variable vascular perfusion to the different regions of the TFCC was thought to create a suboptimal biologic environment for the healing of repairs. This is known to be especially true in the central portion of the disc, where vascular penetration is negligible.6,8,9

Several investigators also questioned whether there was significant penetration of vessels in the radial aspect of the TFCC, and proposed that class 1D lesions be treated in a similar fashion to central lesions (with debridement).6 Second, biomechanical studies of the stability of the horizontal disc showed that no significant kinematic or structural changes result if debridement involves less than two-thirds of the disc and spares the peripheral 2 mm of the disc.5

Currently, the optimal treatment for radial-sided avulsions of the TFCC is a subject of considerable controversy. When compared to arthroscopic repair, the advantages of arthroscopic debridement include decreased operative time, decreased recovery time (with a shorter period of immobilization), fewer complications, and better range of motion.14

We have previously shown that in 52 patients arthroscopic debridement of TFCC tears provided complete relief of pain in 73%. Of these lesions, 34% were radial-sided tears. Our technique consisted of using small pituitary rongeurs or punches, as well motorized shavers to debride the defect edges. We noted no clinical ulnar wrist instability in follow-up. Similar outcomes were recently reported by Husby and Haugstvedt, who demonstrated excellent clinical outcomes after arthroscopic debridement of central and radial TFCC tears (with high patient satisfaction and no complications).29

Despite convincing data regarding the functional outcomes in patients undergoing debridement of radial-sided TFCC lesions, further research has emphasized the importance of the peripheral attachments of the TFCC in stabilizing the distal radioulnar joint. These attachments also provide support for the ulnocarpal joint.4,11 This observation has led several investigators to advocate repair of certain peripheral TFCC tears in order to increase stability.25,30,31 A number of techniques for reattachment of class 1B and 1C TFCC tears have been described with positive clinical results, confirming the ability of lesions in these regions to heal. The optimal treatment of radial-sided class 1D lesions remains controversial.

It is uncommon for a class 1D tear to cause instability of the DRUJ in the absence of a distal radius fracture, which is the most common cause of DRUJ instability.26 The examiner should examine the volar and dorsal aspects of the wrist and forearm for swelling and symmetry with the other wrist. Increased anteroposterior translation of the ulna on the radius during passive movement of the DRUJ when compared to the contralateral side provides evidence for instability.32 A provocative maneuver for DRUJ instability can be performed by depressing the patient’s distal ulna from dorsal to volar with the wrist in pronation. A positive piano-key sign is characterized by volar laxity of the ulnar head in the affected wrist when compared with the contralateral wrist.

In the setting of a distal radius fracture with concomitant DRUJ instability, accurate fracture reduction and maintenance of the reduction are imperative for healing of the disrupted joint.33 After reduction of a distal radius fracture, it is important to test the stability of the DRUJ. The secondary stabilizers of the DRUJ (namely, the ulnocarpal ligaments, ECU subsheath, interosseous membrane, and lunotriquetral interosseous ligament) typically maintain sufficient stability of the joint to allow healing after fracture reduction.34 If, however, a radial TFCC tear is identified during the arthroscopic treatment of a distal radius fracture securing the radial side of the disc to the sigmoid notch using a 0.035-inch Kirschner wire will typically promote healing of the radial attachment. Severe or bidirectional DRUJ instability that persists after fracture reduction and fixation indicates that the secondary stabilizers of the DRUJ, including the TFCC, have been progressively injured and may be contributing to joint instability. In this situation, open repair of the TFCC may be indicated.

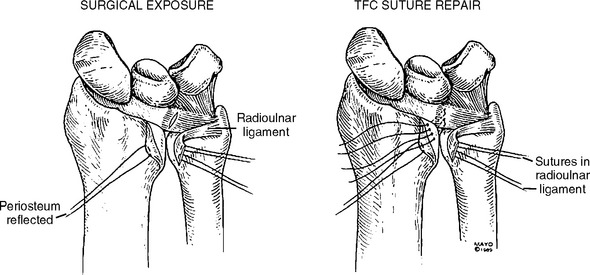

Repairing the torn TFCC to the sigmoid notch of the radius has been described using both open and arthroscopic approaches. Cooney described a technique for an open suture repair of peripheral lesions through a dorsal approach (Figure 4.9).35 Thirty-three patients with peripheral rim tears not associated with instability of DRUJ joint underwent open repair, combined with debridement of the ulnar border of the radius to promote vascular ingrowth. He reported good to excellent results in 80% of the patients. At two-year follow-up, MRI showed continuity of the repair in a small subgroup of patients within the series.

FIGURE 4.9 Repair of a class 1D injury using an open, dorsal approach and placement of transosseus sutures.

(Reproduced with permission by Cooney WP, Linscheid RL, et al. Triangular fibrocartilage tears. J Hand Surg [Am] 1994;19:143–54.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree