Arthroscopic Treatment of Posterior Shoulder Instability

Fotios P. Tjoumakaris

James P. Bradley

DEFINITION

Posterior shoulder instability results in pathologic glenohumeral translation ranging from mild subluxation to traumatic dislocation. Most patients with this pathologic entity report pain in provocative positions of the glenohumeral joint, a condition referred to as recurrent posterior subluxation.

Posterior shoulder instability is much less common than anterior instability, representing about 5% to 10% of all patients with pathologic shoulder instability.2,5,10

A decision must be made regarding surgical treatment of this condition when an extended trial of conservative measures, such as physical therapy, has failed.

ANATOMY

The important stabilizing structures of the glenohumeral joint are the articular surfaces and congruity of the humerus and glenoid of the scapula, the capsular structures, the glenoid labrum, the intra-articular portion of the biceps tendon, and the rotator cuff muscles.

Pathologies of the posterior capsule and labral complex are believed to be the main contributors to posterior instability.

With the arm forward-flexed to 90 degrees, the subscapularis provides significant stability against posterior translation, and as the arm is placed in neutral, the coracohumeral ligament resists this force. With internal rotation of the shoulder (follow-through phase of throwing), the inferior glenohumeral ligament complex is the main restraint to posterior translation.1

Histologic evaluation of the posterior capsule shows it to be relatively thin and composed of only radial and circular fibers, with minimal cross-linking.

PATHOGENESIS

Posterior instability can be the result of trauma in the form of a direct blow to the anterior shoulder or may occur as the result of indirect forces acting on the shoulder, causing the combined movements of shoulder flexion, adduction, and internal rotation.11,12,13

Electrocution and seizures are the most common causes of an indirect mechanism resulting in posterior dislocation.

Patients with recurrent posterior subluxation may present with more vague symptoms, with pain being the chief complaint. Athletes may report that velocity with throwing is diminished, and a sharp pain may accompany the follow-through phase of throwing.

Other associated injuries such as superior labrum anterior posterior (SLAP) lesions, rotator cuff tears, reverse Hill-Sachs defects, and chondral injuries may be present and contribute to the pathology.4

NATURAL HISTORY

Patients with a history of a chronically locked posterior dislocation are at increased risk for the development of chondral injury and subsequent degenerative arthritis.6

Static posterior subluxations of the humeral head have been correlated with the presence of arthritis in young adults whose instability was left untreated.14

No long-term studies on the arthroscopic treatment of shoulder instability have documented a reduction in the development of osteoarthritis.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A thorough history is obtained, documenting whether a dislocation has occurred (as well as the need for closed reduction) or if the primary symptoms are pain.

The circumstances regarding pain are documented, namely onset (provocations), severity, ability to participate in sports, and whether symptoms are present at rest.

Any response to conservative treatment (ie, physical therapy, rest, anti-inflammatory medication) should be noted.

As with the examination of any joint, the shoulder is palpated to elicit tenderness and range of motion is documented. Any restriction in motion should be compared to the contralateral extremity, and differences between active and passive motion may indicate pain or capsular contracture.

Impingement signs are tested to determine whether any associated rotator cuff tendinitis is present.

Other examinations for posterior instability are as follows:

Strength testing. Weakness may be the result of deconditioning or may indicate underlying rotator cuff or deltoid pathology.

Load and shift test. The degree of pathologic subluxation is assessed, as well as any apprehension or pain experienced by the patient during provocative testing.

Jerk test. A positive jerk test indicates pathologic posterior subluxation.9

Kim test. A positive Kim test suggests a posteroinferior labral tear or subluxation.8

Circumduction test. A positive test result is highly suspicious of posterior subluxation or dislocation.

Sulcus sign evaluation. A positive sulcus sign suggests multidirectional instability.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

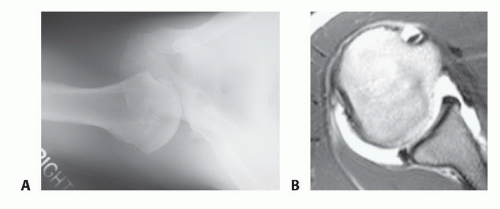

Plain radiographs, including a glenohumeral anteroposterior view, scapular Y view, axillary lateral view, and supraspinatus outlet view, should be obtained to rule out associated injuries, bone defects (either humeral or glenoid), or degenerative changes (FIG 1A).

Magnetic resonance (MR) arthrography is currently the best method for imaging the posterior capsulolabral structures.

Findings on MR suggestive of posterior instability are posterior humeral head translation, posterior labral injury, posterior labrocapsular avulsion, humeral avulsion of the posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament, posterior glenoid bone defects, and anterior humeral head bone defects (FIG 1B).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Posterior shoulder dislocation (may be locked)

Recurrent posterior subluxation

Multidirectional instability

Internal impingement

SLAP tear

Rotator cuff tear

Acromioclavicular joint injury

Fracture (eg, glenoid, greater tuberosity)

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

An extended period of nonoperative management is warranted in most cases of posterior shoulder instability.

Nonoperative therapy constitutes physical therapy to regain a full and symmetric shoulder range of motion, with later emphasis placed on strengthening the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizing muscles.

The premise of a conditioning program is to enable the dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder to compensate for the deficient static stabilizers (eg, capsule, labrum).

Once full motion and strength are achieved, return to sport is gradually introduced.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical management of posterior instability is considered when an exhaustive rehabilitation program has failed to alleviate disabling posterior subluxation or when instability is the result of a macrotraumatic event. Recent advances in the treatment of posterior shoulder instability have resulted in a mostly arthroscopic approach, which is detailed in the following texts. The current method has evolved to a zone-specific technique, using traditional knot fixation in the inferior glenoid and knotless fixation as the repair is taken superiorly. This technique has reduced the incidence of symptomatic engagement of the humeral head against sutures during normal glenohumeral motion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree