Arthroscopic Treatment of Multidirectional Shoulder Instability

Steven B. Cohen

DEFINITION

Neer and Foster20 described the concept of multidirectional instability (MDI) of the shoulder in detail in 1980.

This established the difference between unidirectional instability and global laxity of the capsule inferiorly, posteriorly, and anteriorly.

Subjective complaints of pain and global shoulder instability

Subluxation or dislocation from traumatic, microtraumatic, or atraumatic injury

ANATOMY

Stability of the shoulder relies on dynamic and static restraints

Static restraints

Inferior glenohumeral ligament

Anterior band resists anterior translation in 90 degrees of abduction and external rotation

Posterior band resists posterior translation in forward flexion, adduction, and internal rotation

Middle glenohumeral ligament

Resists anterior translation in 45 degrees of abduction

Superior glenohumeral ligament

Resists posterior and inferior translation with arm at side

Rotator interval/coracohumeral ligament

Resists posterior and inferior translation with arm at side

Dynamic restraints

Rotator cuff muscles

Deltoid

Effects of concavity and compression

Shoulder instability has been found to be a result of several pathologic processes:

Capsular laxity

Labral detachment/Bankart lesion

Rotator interval defects

Bony defects of humeral head (Hill-Sachs lesion) or glenoid

PATHOGENESIS

Typically, there is not a history of a traumatic shoulder dislocation, but there may be the inciting event. Most commonly, the instability is due to microtrauma resulting in global capsular laxity. There may be a history of recurrent dislocations or repetitive subluxation events. This may occur in overhead athletes such as swimmers and volleyball players.

Young active patients

Pain

Complaints of shoulder shifting/subluxation

Difficulty with overhead activity

Inability to do sports

Instability while sleeping/night pain

Trouble with activities of daily living

Episodes of “dead arm” sensation

Failed prior attempts at physical therapy

NATURAL HISTORY

Unable to change static restraints

Stability can be achieved by restoring neuromuscular control through rehabilitation.

Recurrent dislocations may lead to Hill-Sachs lesions, glenoid erosion, and/or chondral injury, which may predispose to early degenerative arthritis of the glenohumeral joint.

Recurrent instability affecting daily activities despite formal physical therapy generally requires surgical treatment.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Infrequent atrophy

Symmetric range of motion

Possible scapulothoracic winging/scapular dyskinesis

Scapular depression

Normal strength testing

Possible core weakness

Evaluation for ligamentous laxity

Frequently positive for generalized ligamentous laxity

Evaluation for impingement

Stability testing

Positive increased load and shift test for anterior and posterior translation

Positive sulcus sign (both in neutral and external rotation) for inferior translation

If sulcus sign graded as 3+ that remains 2+ in external rotation is pathognomonic for MDI—rotator interval lesion.

Evaluation of ligamentous laxity (Beighton scale)

Specific tests which may or may not be positive

Apprehension test

Relocation test

O’Brien sign

Mayo shear test

Jerk test

Kim test

Circumduction test

Speed test

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs

Anteroposterior view

Axillary lateral or West Point axillary view

Outlet view

Stryker notch view

Evaluate for

Hill-Sachs or reverse Hill-Sachs lesion

Glenoid pathology

Bony humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments (HAGL)

Magnetic resonance arthrogram (MRA)

Evaluate for

Capsular laxity

Labral pathology

HAGL

Biceps tendon pathology

Rotator cuff lesions (rare)

Computed tomography (CT)

Evaluate for

Proximal humeral/glenoid bony pathology

NONOPERATIVE TREATMENT

In many cases with patients with atraumatic MDI, the proper neuromuscular control of dynamic glenohumeral stability has been lost.

The goal is to restore shoulder function through training and exercise.

Patients with loose shoulders may not necessarily be unstable as evidenced by examining the contralateral asymptomatic shoulder in patients with symptomatic MDI.

The mainstay of treatment is nonoperative, with attempts to achieve stability using scapular, core, and glenohumeral (rotator cuff) strengthening exercises.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Indications

Patients who have attempted a (or several) dedicated program(s) of physical therapy, have functional problems, and remain unstable may then be candidates for surgical treatment.

History of MDI with sustained fractures of the glenoid or humeral head with a dislocation generally require surgical treatment.

Significant defects in the humeral head associated with multiple dislocations consistent with engaging Hill-Sachs lesions may require earlier surgical treatment.

Glenoid erosion or lip fractures, if significant, can also necessitate surgical intervention if associated with recurrent instability.

Contraindications

Patients with voluntary or habitual instability

Patients who have not attempted a formal physiotherapy program should avoid initial surgical treatment.

Any patient unable or unwilling to comply with the postoperative rehabilitation regimen

Preoperative Planning

Patient education is critical in planning surgical treatment for the patient with an unstable shoulder.

The patients should have failed a trial at nonoperative treatment and have persistent instability with functional deficits.

The goal of surgical treatment is to reduce capsular volume and restore glenoid concavity with capsulolabral augmentation.

By decreasing capsular volume, range of motion may be decreased as a result.

It is important to discuss this possibility with the patient as some more active athletic patients such as throwers, gymnasts, swimmers, and volleyball players may not tolerate losses of motion to maintain participation in their sport.

Additional risks and benefits should be discussed including the risk of infection, recurrence of instability, pain, neurovascular injury, persistent functional limitations, and implant complications.

The surgical planning continues with the evaluation under anesthesia and diagnostic arthroscopy.

This may alter the plan to include any combination of the following: capsular plication (anterior, posterior, and/or inferior), rotator interval closure, anterior/posterior labral repair, superior labrum anterior posterior repair, biceps tenodesis/tenotomy, and possible conversion to an open capsular shift.

If sulcus sign remains similar in external rotation, then may consider rotator interval closure

Anesthesia and Positioning

The procedure can be performed under interscalene block or general endotracheal anesthesia with an interscalene block for postoperative pain control.

The patient can then be placed in the lateral decubitus position with the affected shoulder positioned superior.

An inflatable beanbag holds the patient in position.

Foam cushions are placed to protect the peroneal nerve at the neck of the fibula on the down leg.

An axillary roll is placed.

The operating table is placed in a slight reverse Trendelenburg position.

The full upper extremity is prepped to the level of the sternum anteriorly and the medial border of the scapula posteriorly.

The operative shoulder is placed in 10 pounds of traction and is positioned in 45 degrees of abduction and 20 degrees of forward flexion.

Alternatively, the beach-chair position can be used. In our experience, this position gives us limited exposure of the posterior inferior capsule.

The head of the bed is raised to approximately 70 degrees with the affected shoulder off the side of the bed with support medial to the scapula.

The head should be well supported and all bony prominences padded.

The entire arm, shoulder, and trapezial region are prepped into the surgical field.

A pneumatic arm holder can be used to position the arm to aid in visualization both anteriorly and posteriorly.

Landmarks/Portals

The bony landmarks, including the acromion, distal clavicle, acromioclavicular joint, and coracoid process, are demarcated with a marking pen.

Following prepping and draping, the glenohumeral joint is injected with 50 mL of sterile saline through an 18-gauge spinal needle to inflate the joint.

A posterior portal can be established 3 cm distal (lower) and 1 cm medial (humeral) to the posterolateral corner of the acromion to allow access to the rim of the posterior glenoid

for anchor placement in the event a posterior labral or capsular repair is necessary.

A superior-anterior portal is then established in the rotator interval via an outside-in technique using a spinal needle. Care should be taken using a spinal needle to verify that a low anterior inferior 5 o’clock anchor can be placed through a second inferior anterior portal. When using two anterior portals, the superior portal should be placed “high” in the interval to make room for the second “low” portal.

If a second anterior portal is desired, it is created using a spinal needle at the level just superior to the subscapularis tendon lateral to the coracoid and a minimum of 1 cm inferior to the anterior portal.

Examination under Anesthesia/Diagnostic Arthroscopy

The examination under anesthesia is performed on a firm surface with the scapula relatively fixed and the humeral head free to rotate.

A “load and shift” maneuver, as described by Murrell and Warren,19 is performed with the patient supine.

The arm is held in 90 degrees of abduction and neutral rotation while an anterior or posterior force is applied in an attempt to translate the humeral head over the anterior or posterior glenoid.

A “sulcus sign” is performed with the arm adducted and in neutral rotation to assess whether the instability has an inferior component.

A 3+ sulcus sign that remains 2+ or greater in external rotation is considered pathognomonic for MDI.

Testing is completed on both the affected and unaffected shoulders and differences between the two are documented.

Diagnostic arthroscopy of the glenohumeral joint

The labrum, capsule, biceps tendon, subscapularis, rotator interval, rotator cuff, and articular surfaces are visualized in systematic fashion.

This ensures that no associated lesions will be overlooked.

Lesions typically seen in MDI include the following:

Patulous inferior capsule

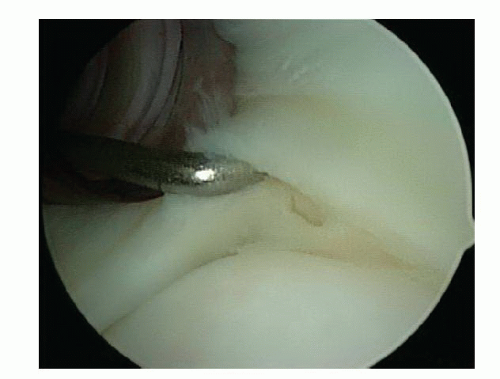

Labral tears (FIG 1) or fraying and splitting

Widening of the rotator interval

Articular partial-thickness rotator cuff tears

After viewing the glenohumeral joint from the posterior portal, the arthroscope is switched to the anterior portal to allow improved visualization of the posterior capsule and labrum.

A switching stick can then be used in replacing the posterior cannula with a 7.0- to 8.25-mm distally threaded or fully threaded clear cannula, thus allowing passage of an arthroscopic probe and other instruments through the clear cannula to explore the posterior labrum for evidence of tears.

TECHNIQUES

Arthroscopic techniques have evolved from capsular shift via transglenoid sutures, Bankart repair and shift with biodegradable tacks or suture anchors, thermal capsulorraphy, rotator interval repair, and capsular plication.

Our current method of treatment for patients with multidirectional shoulder instability who have failed nonoperative attempts is to perform an arthroscopic capsular shift by reducing capsular volume using capsular plication with a multipleated repair.26

▪ Specific Steps

Preparation for Repair

The arthroscope that remains in the posterior portal and the anterior portals serve as the working portal for the anterior repair and vice versa for the posterior repair.

The side (anterior or posterior) that is least unstable is fixed first. For example, if posterior instability is the most severe direction, the anterior and inferior sides are fixed first and the posterior capsule and labrum is addressed last.

An arthroscopic rasp or chisel is used to mobilize any torn labrum from the glenoid rim (TECH FIG 1A).

A motorized synovial shaver or meniscal rasp is used to abrade the capsule adjacent to a labral tear and to débride and decorticate the glenoid rim to achieve a bleeding surface for capsular plication (TECH FIG 1B).

Capsular Plication (TECH FIG 2A)

A 3.0-mm Bio-SutureTak anchor loaded with no. 2 FiberWire (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) is placed in the 5 o’clock position (right shoulder) for the anterior repair and 7 o’clock position for the posterior repair and the sutures brought out through the working portal (TECH FIG 2B).

The anchor can be placed through the cannula or percutaneously.

A soft tissue penetrator (Spectrum Suture Hook, Linvatec, Corp., Largo, FL) or crescent suture passer is passed through the labrum directly adjacent to the anchor and the inferior FiberWire on the anchor is pulled through the labrum (TECH FIG 2C).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree