Arthroscopic Repair of Rotator Cuff Tears

Laurent Lafosse

L. Lafosse: Annecy, France.

INTRODUCTION

The surgical management of rotator cuff tear (RCT) is established by the patient’s need for pain relief and improved function and the surgical feasibility based on the surgeon’s experience and expertise. The associated symptoms may be explained by subacromial impingement with or without a rotator cuff tear. Historically, French surgeons divided the treatment options into two groups. One group recommended an isolated acromioplasty and obtained satisfactory results in terms of pain, mobility, and function, but without restoring the strength of the shoulder and potentially allowing further increase in the size of the tear and progression of arthritis.2 The other group proposed isolated tendon tear repair without treating the impingement, a treatment mode that was followed by a high rate of rerupture. Didier Patte was the first surgeon in Europe to combine the two methods and developed the classic anterior release technique called “Grande Liberation Antérieure.” This rather aggressive method excised the acromioclavicular articulation and raised four delto-trapezoid flaps, exposing the posterosuperior cuff and the upper third of the subscapularis tendon.

Charles Neer, in the United States, described a less invasive method, which involved an anterior approach to the acromion and cuff starting with an acromioplasty. Potentially, this method allowed simultaneous treatment of impingement and the possibility of tendon repair.21,22 At the beginning of shoulder arthroscopy, only the acromioplasty was performed arthroscopically. Later on, the rotator cuff repairs were managed by adding a small lateral approach and minimally separating the deltoid fibres to access the ruptured tendon.1,8,10,20 In 1988, G. Gartsman published the first results of full arthroscopic rotator cuff repair.9

Indications and techniques for management of rotator cuff tears differ among authors. Some manage them only by acromioplasty (mostly arthroscopically).20,14,23,26 Others always avoid acromioplasty13 when they repair the cuff. Rotator cuff repair can be done by open, mini-open, or arthroscopic technique. The author started arthroscopic technique in 1992 and, since 2000, has managed all rotator cuff repairs arthroscopically.

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT

When preparing to perform an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (ARCR), it is necessary to establish a set of preoperative data that includes the following: functional evaluation, clinical evaluation, imaging, and classification of the rotator cuff tear.

Functional Evaluation

A patient questionnaire must be completed, providing the functional information necessary to complete the Constant University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeon (ASES) shoulder scores.4,7,25 One should assess the patient’s level of pain, limitation in athletic and work activities, and limitation in his or her activities of daily living. If a patient is unclear on how to answer these questions, the physician or office staff should help clarify the questions.

Clinical Evaluation

Atrophy of the deltoid, the supraspinatus, and the infraspinatus muscles should be evaluated. Passive range of

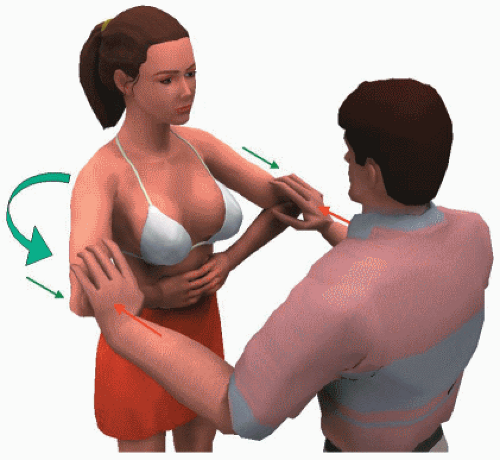

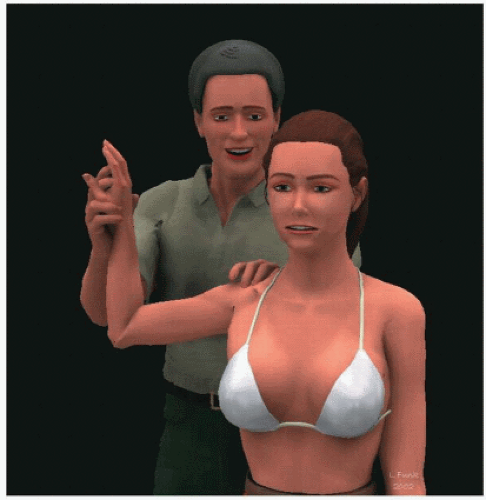

motion and tenderness of the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints are evaluated to rule out alternate or additional causes of pain and disability other than RCT. The passive and active mobility of both shoulders is measured, beginning with the unaffected side. The supraspinatus strength is tested with the Jobe sign.16 This may be unreliable due to pain-related weakness. The infraspinatus strength is tested by performing external rotation lag sign with the elbow at the side, and the subscapularis strength is tested by the liftoff test if internal rotation is not limited and by the belly-press test as described by Gerber et al12 and modified by pushing against the elbow of the patient (Fig. 8-1). Clinical evaluation of symptoms from the long head of the biceps is more difficult. The author uses the abduction rotation external supination (ARES) and abduction rotation internal supination (ARIS) test. In this test the patient does a forced supination against resistance, with the arm positioned in 90 degrees of abduction and 90 degrees of external rotation (ARES) (Fig. 8-2) or internal rotation (ARIS) (Fig. 8-3). In both situations, the biceps must be a normal tendon and must have good anterior (in external rotation) and posterior (in internal rotation) ligaments at the entrance of the groove to be stable. When the biceps is damaged and/or unstable, subluxation of the tendon will occur over the edge of the bony groove and may be painful or weaker than on the other side. Strength is measured by a simple handheld spring scale placed around the wrist with the elbow outstretched.

motion and tenderness of the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints are evaluated to rule out alternate or additional causes of pain and disability other than RCT. The passive and active mobility of both shoulders is measured, beginning with the unaffected side. The supraspinatus strength is tested with the Jobe sign.16 This may be unreliable due to pain-related weakness. The infraspinatus strength is tested by performing external rotation lag sign with the elbow at the side, and the subscapularis strength is tested by the liftoff test if internal rotation is not limited and by the belly-press test as described by Gerber et al12 and modified by pushing against the elbow of the patient (Fig. 8-1). Clinical evaluation of symptoms from the long head of the biceps is more difficult. The author uses the abduction rotation external supination (ARES) and abduction rotation internal supination (ARIS) test. In this test the patient does a forced supination against resistance, with the arm positioned in 90 degrees of abduction and 90 degrees of external rotation (ARES) (Fig. 8-2) or internal rotation (ARIS) (Fig. 8-3). In both situations, the biceps must be a normal tendon and must have good anterior (in external rotation) and posterior (in internal rotation) ligaments at the entrance of the groove to be stable. When the biceps is damaged and/or unstable, subluxation of the tendon will occur over the edge of the bony groove and may be painful or weaker than on the other side. Strength is measured by a simple handheld spring scale placed around the wrist with the elbow outstretched.

Imaging

Imaging includes:

Radiographs: true A-P, outlet-view, and acromioclavicular. The height of the subacromial space, arthritis by Samuelson score, and the condition of the acromioclavicular articulation are evaluated.

Arthro-CT scan to define the morphology of the tendon tear and to assess muscular atrophy and fatty degeneration.14 In the author’s practice the Arthro-CT has more specificity and sensitivity than MRI.

Arthro-MRI is only required for a partial tear that we evaluate with the Codman classification.3

Classification of the Rotator Cuff Tear

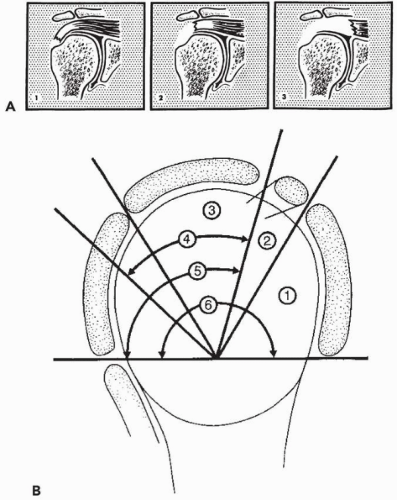

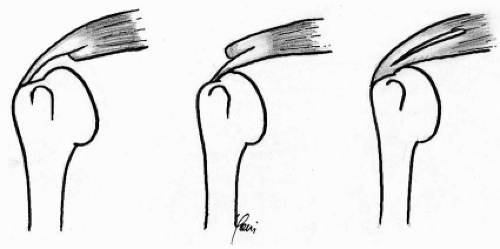

The author uses the Patte classification,24 which evaluates the retraction and location of the tear within sagittal and coronal planes (Fig. 8-4). Partial tears are classified as deep, superficial, or intratendinous (Fig. 8-5). A modified Patte classification defines massive tears: at least three involved tendons of which at least one is retracted to the glenoid.

SURGICAL PRINCIPLES

Anesthesia

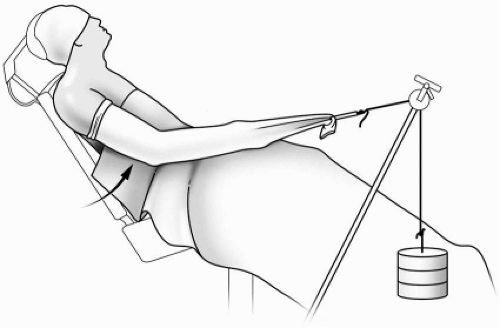

An interscalene block is performed with or without general anesthesia. The patient is placed in a fully seated, upright position with the arm flexed forward and under traction by weights of about 3 kg (Fig. 8-6). This procedure can be done in the lateral decubitus position, but the author prefers the seated position.

Portals

Five approaches are currently used (Fig. 8-7). The first classical posterior glenohumeral approach is used for the scope, that we translate 3 cm medially as modified by Jan Leudzinger, when AC joint access is planned. A second posterosuperior approach, situated at the posterolateral angle of the acromion, is used for viewing the subacromial space. The two instrument portals are initially localized using a spinal needle working from outside-in, representing the classical lateral acromioplasty portal and another anterior portal near

the coracoacromial ligament. The fifth approach is anterosuperior at the anterolateral corner of the acromion.

the coracoacromial ligament. The fifth approach is anterosuperior at the anterolateral corner of the acromion.

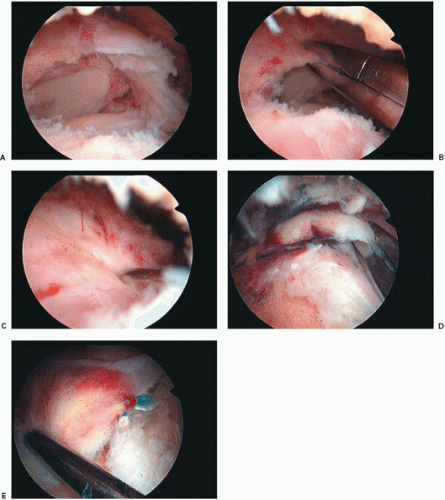

Figure 8-8 Cuff tear: (A) U-shape, (B) Tendon grasped, (C) Reduced, (D) L-shape, and (E) L-shape reduced. |

Before arthroscopy, 20 cc of 1% lidocaine with epinephrine are injected into the glenohumeral articulation and the subacromial bursa to reduce bleeding.

Diagnostic Arthroscopy

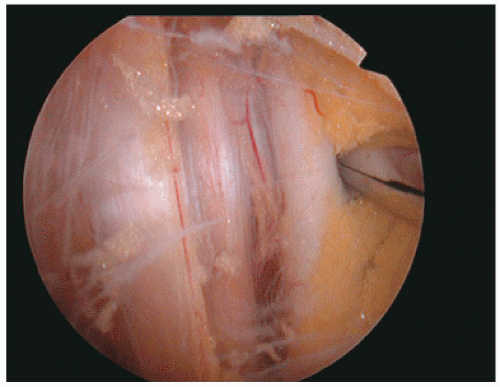

A systematic assessment of the glenohumeral and subacromial space is done both statically and dynamically, and the tissue is probed for stability. After a complete visualization,

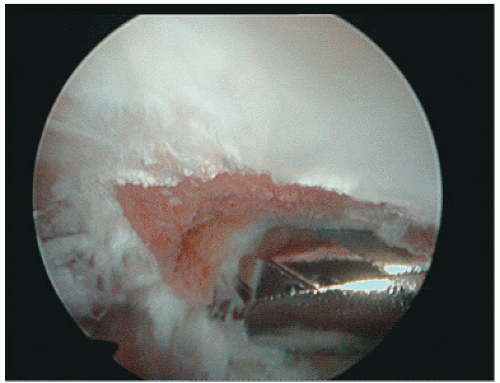

the degree of cuff retraction and mobilization to the insertion site is tested. When needed a periglenoid capsular and subacromial release is performed so that the tendon can be easily pulled to the tuberosity with the arm by the patient’s side. The release is essential to perform the repair without excessive tension. Mobilization is performed from medial to lateral for U-shape tears (Fig. 8-8, A-C) or by reducing with traction on the tendon combined with humeral rotation in L-shape tears (Fig. 8-8, D and E). Special attention is given when delamination occurs to repair both deep and superficial leaves of the tear; this is more commonly seen in massive posterior cuff tear.

the degree of cuff retraction and mobilization to the insertion site is tested. When needed a periglenoid capsular and subacromial release is performed so that the tendon can be easily pulled to the tuberosity with the arm by the patient’s side. The release is essential to perform the repair without excessive tension. Mobilization is performed from medial to lateral for U-shape tears (Fig. 8-8, A-C) or by reducing with traction on the tendon combined with humeral rotation in L-shape tears (Fig. 8-8, D and E). Special attention is given when delamination occurs to repair both deep and superficial leaves of the tear; this is more commonly seen in massive posterior cuff tear.

The stability of the origin of the long head of the biceps tendon is evaluated with a probe. Its stability within the groove is inspected while the arm is passively moved into internal and external position in order to assess the anterior and posterior pulley. Instability may require repair, tenodesis, or tendon release.

The plan for further treatment is made intraoperatively based on cuff tear size as described by Patte, on the ability to mobilize the cuff to the tuberosity, and on the biceps tendon and muscle quality,.

Release

For large retracted tears the intra-articular capsular and subacromial release is essential to mobilize the tear and decrease the traction on the repair. This is performed with a radiofrequency device (VAPR Mitek, Johnson and Johnson, Norwood, MA).

For posterosuperior cuff tears, the coracoacromial ligament is released from the base of the coracoid at the anterosuperior edge of the glenoid rim with intra-articular assessment. The capsule is released above the labrum from the anterior superior to posterior superior quadrants. Release bursal side scar tissue is removed medially until the cuff muscle is seen.

Special care must be given to the subscapularis release for massive retracted tendons because it usually requires visualization of the axillary nerve and the medial plexus with the axillary artery (Fig. 8-9). This can be a dangerous part of the surgery that should not be done by arthroscopy without advanced expertise.

Acromioplasty

Acromioplasty is systematically performed in addition to the tendon repair, except for massive, partially repairable ruptures where the CA arch is the last structural element to keep superior stability and avoid anterior superior escape of the humeral head. If lack of space impedes the exposure or the passage of the instruments, acromioplasty is performed prior to repair of the tendon. Otherwise it is done after repair to avoid additionalbleeding during the repair. The coracoacromial ligament is released with an electrocautery. A burr is used to remove bone from the acromion starting at the anterior lateral corner and proceeding medial to the AC joint to achieve a flat type I acromion (Fig. 8-10).

AC Joint Resection

When necessary, AC joint resection is done after acromioplasty in three steps:

Using the posterolateral portal for visualization, the soft tissue and medial portion of the acromial facet of the AC joint are removed, exposing the distal clavicle. The inferior osteophyte of the distal clavicle is removed.

An anterior superior portal is placed into the AC joint, to introduce the burr. Bone is removed from both the acromion and clavicle bone with visualization from the lateral portal. Special care must be taken to remove the posterior and superior clavicle spur, while preserving the attachment of the posterior and superior AC capsular ligaments.

A final posterior visualization from the modified posterior portal (previously described) checks the anterior clavicle, ensuring that the superior AC ligament is intact (Fig. 8-11).

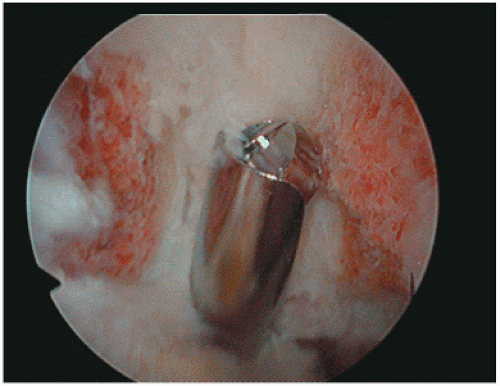

Tendon Fixation

Anchors. The type of fixation depends on the bone quality and influences the technique used for anchor insertion. The use of push-in anchors (vs. thread in anchors) enables the surgeon to first pass a suture through the cuff, then load the anchor with the suture and place the anchor in bone. When using screw-in anchors or anchors with two preloaded sutures, an anchor-in first technique is required. The author typically uses metallic implants and reserves the use of absorbable anchors. Tendon attachment is close to articular cartilage when restoring the medial foot print of the rotator cuff or when performing a biceps tenodesis.

Location of the fixation is done according to the lesion, but whenever possible, restoring the normal footprint of the rotator cuff is performed by adding a double row of anchors. One row restores the lateral tendon attachment and the other medial cartilaginous attachment.

Suture No. 2 or No. 3 is always a braided nonabsorbable. PDS sutures break before tendon healing.

Different techniques to pass the braided suture through the tendon using different devices must be available.

A two-step technique uses a suture passer (Spectrum, Linvatec, Largo, FL) equipped with a 45-degree curved hook (left-rotated mostly used for a right shoulder and vice versa), loaded with a simple PDS No. 0 pushed through the hook (Fig. 8-12A). The PDS is grasped by forceps and can be pulled out through the same or a different portal easily (the length is as long as necessary), even during or after the suture passer is through the tendon. The PDS is easily used as a shuttle relay for passing a nonabsorbable suture, which is already fixed to an anchor (Fig. 8-12B). This avoids any twist or soft-tissue interposition when many sutures are used (Fig. 8-12C).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree