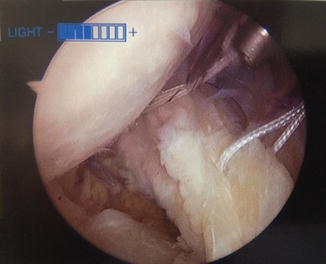

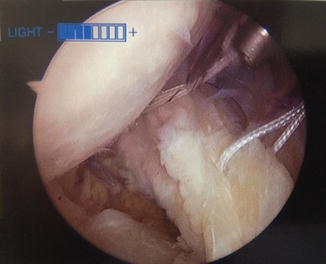

Fig. 20.1

A and B. Margin convergence. Side-to-side sutures are used to close down the defect and take tension off of the repair to the bone (Figure 20.1A reprinted from Burkart SS, Lo IKY. Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2006; 14(6) with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health Inc.)

Force Couple: Value of Subscapularis and Infraspinatus, True Humeral Head Depressors

The “force couple ” is an important principal of rotator cuff repair and is essential to understand when treating massive cuff tears. The muscles of the rotator cuff and shoulder girdle are positioned to create moments about the shoulder that will produce stable rotational motion (Fig. 20.2). The shoulder can only maintain a stable fulcrum of motion when it maintains this balanced relationship in both the coronal and sagittal plane [14, 32]. With massive rotator cuff tears, these synergistic forces are disrupted and the shoulder can no longer maintain a stable fulcrum, resulting in decreased range of motion and sometimes pseudoparalysis. The superior pull of the deltoid overcomes the absent “concavity compression,” usually afforded by the humeral head depressors. If repair of a massive rotator cuff tear is performed using surgical techniques that ignore the innate biomechanics of the shoulder, it is destined to fail. Function can be restored even in the presence of a persistent defect as long as the anterior and posterior forces are rebalanced.

Fig. 20.2

Diagram demonstrating the concept of the force couple. All shoulder forces must remain in balance in order to maintain a stable fulcrum of motion (Reprinted from Burkart SS, Lo IKY. Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2006; 14(6) with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health Inc.)

Visualizing the Tear

The senior author prefers the lateral decubitus position, as it affords excellent visualization of the entire cuff, including the subscapularis.

A posterior portal is made in standard fashion with the portal established slightly lateral to the convexity of the humeral head. The camera is placed in the subacromial space through the posterior portal, and a thorough bursectomy is performed. A lateral working portal is then established under direct visualization. The portals should be place low enough such that the cannulas are parallel with the rotator cuff tendons. A second lateral portal can be established for large tears in order to obtain a “50-yard line view” of the tear.

Tear Pattern Recognition

In order to perform a successful repair of a massive tear one must first be able to recognize the tear pattern. Most massive rotator cuff tears can be broadly classified into various patterns: crescent-shaped tears, “L”-shaped tears, “reverse L”-shaped tears, and U-shaped tears. L-, reverse L-, and U-shaped tears comprise approximately 40 % of all tears and 85 % of the large and massive tears [31]. They comprise the majority of large and massive tears and extend further medial than crescent-shaped tears. The apex often extends medial to the glenoid rim. Again, it is important to realize that this medial extension of the tear does not represent retraction but rather represents the resting shape that a large tear assumes under physiologic load from its muscle-tendon components [10, 30]. Recognizing the tear pattern is critical because attempting to medially mobilize and repair the apex of the tear to a lateral bone bed will result in extreme tensile stresses in the middle of the repaired cuff margin, causing tensile overload and subsequent failure. Crescent-shaped tears, even large and massive tears, typically pull away from the bone but do not retract far. Therefore, they can be repaired directly to the bone with minimal tension.

Repairing the Crescent-Shaped Tear

Crescent-shaped tears usually can be easily repaired to the bone without tension. The senior author prepares a bleeding bone bed on the humerus just adjacent to the articular margin. A power shaver is used to achieve this. Care is taken not to decorticate the bone as this will weaken anchor fixation. A bleeding bone bed is all that is needed to promote tendon healing to the bone [21]. Suture anchors placed at 45° to the bone surface are the preferred means of fixation as studies have demonstrated that bone fixation by suture anchors is stronger than fixation by trans-osseous bone tunnels [33]. The goal is to avoid tension. Therefore, the suture anchors should be placed in a crescent shape just off the articular surface [10]. Viewing from a posterolateral portal allows excellent visualization while an anterograde suture shuttling device may be deployed from a direct lateral portal. Alternatively, a “50-yard line” view may be employed and sutures may be retrieved via a retrograde fashion using percutaneous instruments anteriorly and posteriorly, or the Neviaser portal may be utilized.

Principles of Repair: Large Tears

The senior author has amassed much experience in negotiating and overcoming failure paths and has compiled a list of helpful “pearls” which should serve the shoulder arthroscopist well.

1.

Start with low distention.

It is easy to “blow up” the shoulder joint and make visualization difficult. Therefore, it is important to start the intra-articular portion of the surgery with a low inflow pressure.

2.

Release the inferior capsule.

Since humeral head migration often ensues after long-standing cuff tears, the senior author has found inferior capsule release reduces tension on the repair and helps effect a proper tear reduction. The use of fine-tip electrocautery and hugging the glenoid works well in effecting a release of the entire IGHL.

3.

Release the CHL.

The senior author does not advocate large interval “slides” as this may further compromise tissue integrity. However, release of the CHL off the coracoid may afford significantly increased lateral excursion of the cuff. CHL release may be done intra-articularly, especially in the presence of a subscapularis tear, by skeletonizing the neck of the coracoid. Alternatively, in the subacromial space, while viewing laterally, an accessory anterolateral portal may be employed to liberate the posterior aspect of the coracoid and thereby release the CHL.

4.

Place traction sutures.

Traction sutures placed in anterior and posterior tear limbs not only help mobilization greatly but also help discern tear “reduction.” For subscapularis tears, traction sutures in the “comma tissue” are invaluable (Fig. 20.3).

Fig. 20.3

Arthroscopic picture of traction stitch placed in order to facilitate lateral mobility of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons

5.

Excavate the cuff.

As Burkhart has described, the cuff must be “excavated” from scar tissue and adhesions in the subacromial space. With a side-viewing portal, thermal devices can be applied to the acromion working posteriorly and medially so that the scapular spine is visualized. Bands of scar that do not insert directly on the humerus are termed “bursal leaders” by Burkhart and should be removed.

6.

Repair the subscapularis.

Subscapularis tears are under-recognized and hold the key to repair of many large cuff tears. Not only is the subscapularis a significant humeral head depressor, it also contains the anterior insertion of the condensation of tissue labeled by Burkhart as the “cable.” The cable tissue is essential to maintaining a stable force couple. Only by repairing the subscapularis with its attendant cable tissue (CHL, SGHL) can abduction power be restored. This principle is elaborated further in the next section.

7.

Preserve the comma.

Again, only by recognizing and preserving the comma tissue can a force couple be restored. Furthermore, restoration of the comma tissue allows retracted posterior cuff tissue to be sewn to or “converged” to. The skilled arthroscopist must recognize the comma tissue and maintain its integrity in order to effect a successful massive cuff tear repair.

8.

Reduce the tear.

Proper tear reduction ensures at least a partial repair may be effected. The power of margin convergence cannot be overstated. This technique should not be abandoned in favor of adding more anchors or more suture.

9.

Accept a partial repair.

Contemporary authors describe results of partial repair as approaching complete repair [34]. If the cable tissue is restored, abduction is greatly enhanced.

10.

Improve biology.

While the results of PRP augmentation are controversial, the senior author believes in the “crimson duvet” principle proposed by Snyder [35]. Using an awl in the uncovered tuberosity may allow marrow progenitor cells to transform into cuff-like tissue and fortify the repair.

11.

Use “ripstop” sutures.

Poor tissue may need some help in holding suture. The use of some of the newer “tape” type of suture serves well as a “ripstop” to prevent anchor suture tearing through tissue. Ripstop sutures are placed first with anchor sutures subsequently placed medially (Fig. 20.4).

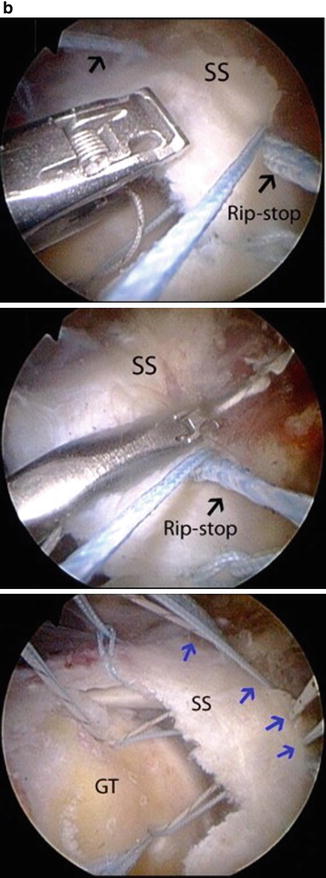

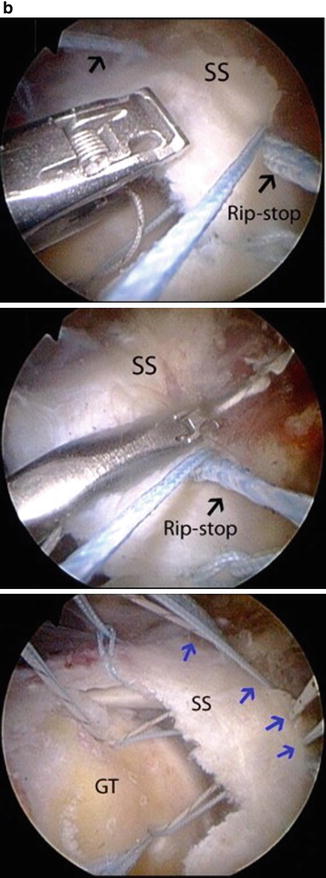

Fig. 20.4

(a) Ripstop stitch (Reprinted from Denard PJ, Burkhart SS. Techniques for Managing Poor Quality Tissue and Bone During Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2011; 27(10):1409–1421 with permission from Elsevier.). (b) Suture limbs from anchor passed medial to ripstop stitch (Reprinted from Denard PJ, Burkhart SS. Techniques for Managing Poor Quality Tissue and Bone During Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2011; 27(10):1409–1421 with permission from Elsevier.)

12.

Obtain multiple fixation points.

The more fixation points, the stronger the construct. The senior author prefers double- and even triple-loaded anchors for this reason. In the setting of massive cuff tears, there is seldom occasion to employ “double-row” fixation, since this would introduce undue tension. Burkhart’s diamondback and rescue anchor repairs [36] utilize medial anchor suture limbs to obtain fixation points laterally (Fig. 20.5).

Fig. 20.5

(a) “Diamondback repair” (Reprinted from Burkhart SS, Denard PJ, Obopilwe E, Massocca AD. Optimizing Pressurized Contact Area in Rotator Cuff Repair: The Diamondback Repair. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2012; 28(2):188–195 with permission from Elsevier.). (b) Rescue anchor technique (Reprinted from Denard PJ, Burkhart SS. Techniques for Managing Poor Quality Tissue and Bone During Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2011; 27(10):1409–1421 with permission from Elsevier.)

13.

Use a “buddy anchor.”

In the presence of poor bone stock, Denard and Burkhart introduced the concept of a “buddy anchor” in order to secure fixation [36]. In the presence of weak pullout strength, stacking an anchor adjacent to the previously inserted one will greatly increase resistance to failure and add fixation points (Fig. 20.6).

Fig. 20.6

“Buddy anchor” insertion technique from Denard and Burkhart (Reprinted from Denard PJ, Burkhart SS. Techniques for Managing Poor Quality Tissue and Bone During Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2011; 27(10):1409–1421 with permission from Elsevier.)

Repairing the U-Shaped Tear

When initially assessing U-shaped tears , they may appear formidable. However, side-to-side sutures often allow dramatic convergence of the cuff to the margin, resulting in a simple repair to the bone. Again, traction sutures placed in both anterior and posterior cuff limbs help with mobilization. If the basic biomechanical principles of balanced force couples and margin convergence are adhered to when addressing the massive U-shaped tear, the patient can achieve a successful clinical and functional outcome.

Repairing the L-Shaped Tear

As noted earlier in the chapter, L-shaped and reverse L-shaped tears are similar to U-shaped tears. The difference is that L-shaped tears have one leaf that is more mobile than the other and therefore can be more easily mobilized to the bone bed. The apex of the L must be identified, and the longitudinal split then sutured in a side-to-side manner. It is critical to note that, when dealing with L and reverse L tears, the mobile limb is brought obliquely (approximately at a 45° angle) to the immobile limb. Tear reduction can be assessed by the absence of a “dog ear.” A “dog ear” should not merely be eliminated with “another anchor” or more suture. They indicate poor reduction and should be revised. After side-to-side sutures are placed, causing margin convergence, the rotator cuff can be repaired to the bone.

Subscapularis and the “Comma Sign”

Multiple studies have reported on repair of combined or isolated subscapularis muscle tears [37–39]. Historically, the subscapularis muscle has been ignored when studying massive rotator cuff tears. However, the subscapularis plays an integral role in the function of the shoulder. The subscapularis seems to be unique among the rotator cuff tendons in that a significant part of its function is a tenodesis function, and it is needed as an anterior restraint [40]. Even without contractile capabilities, it still can help provide a stable fulcrum of motion.

Surgeons may have ignored the subscapularis historically because identifying tears of the subscapularis has been difficult out of merely a lack of awareness. With a chronic isolated or combined complete tear, the tendon is often retracted medially and scarred to the deltoid fascia. Burkhart et al. described the “comma sign ,” which is a marker of the torn subscapularis stump and can be useful even when tackling chronic retracted subscapularis tears [41]. Locating the “comma sign” is integral in differentiating the subscapularis from the conjoined tendon and the coracoacromial ligament. The humeral insertion of the subscapularis, superior glenohumeral ligament, and the coracohumeral ligament is in close proximity and is interconnected, so the entire complex is torn together when the subscapularis tears from the lesser tuberosity. The comma tissue usually remains attached to the superolateral corner of the subscapularis tendon. This residual tissue appears as a comma shape at the superolateral border of the muscle and reliably directs the surgeon to the superolateral portion of the subscapularis (Fig. 20.7) [42, 43]. Subscapularis repair is critical as restoration of the comma tissue (coracohumeral and superior glenohumeral ligaments) will restore the anterior aspect of the “cable” tissue as well as afford tissue to sew to for the superior cuff repair. Retracted infraspinatus tears can be sewn to comma tissue once the subacromial space is entered.

Fig. 20.7

Arthroscopic view of the comma tissue while repairing a subscapularis tear

Although the subscapularis tendon can be repaired using an open technique, the senior author favors arthroscopic treatment for its better visualization of the intra-articular subscapularis tendon, as well as for the increased mobilization it provides [43]. Occasionally, a 70° arthroscope is necessary to adequately visualize the entire subscapularis footprint. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed, and careful inspection of the subscapularis tendon is carried out. Abduction and internal rotation of the arm can facilitate the visualization of the subscapularis footprint. The “posterior lever push” maneuver has been described by Burkhart to improve visualization. In this technique, the elbow is grasped while a posterior force is placed on the humerus. This movement allows the intact subscapularis fibers to pull away from the footprint, allowing the surgeon to better see the subscapularis insertion site. Burkhart and Brady report that this technique may increase the field of view by 5–10 mm [42].

The size and tear pattern are then assessed. In cases of retracted tears, the “comma sign ” is identified which helps delineate the superolateral subscapularis margin. Once the subscapularis insertion site is evaluated, a thorough assessment of the medial sling and bicipital groove must also be performed. Medial dislocation of the biceps secondary to a tear of the insertion of the sling can often be seen with tears of the upper subscapularis. The biceps tendon can be assessed by inserting a probe through an anterior portal and tugging on the tendon. If appreciable medial subluxation is present, a biceps tenotomy or tenodesis is required in order to enhance visualization and protect the repair.

After a tear of the subscapularis has been identified, subsequent repair should be performed before other shoulder areas are addressed. Burkhart describes three portals to repair the subscapularis [44]. The technique is described in more detail in another chapter. The posterior portal is the primary viewing portal. An anterosuperolateral portal is made just anterior to the biceps tendon and anterolateral edge of the acromion which is used to prepare the footprint and repair the tear. An anterior portal, just lateral to the coracoid, is used for anchor placement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree