CHAPTER 24 Arthroscopic Radial Styloidectomy

Introduction

Radial styloidectomy has typically been employed as a palliative procedure for any condition that results in painful impingement between the scaphoid and the radial styloid. It is most attractive to patients who wish minimal surgical intervention, but it does not address the underlying cause and hence may not be a long-term solution. Recommendations for the amount of bony resection have become more conservative with time due to several biomechanical studies that demonstrated increasing radial instability, with the risk of ulnar translocation and progressive loss of the strong volar radiocarpal ligaments.1,2

Osterman has written extensively on an arthroscopic technique that not only allows an assessment of the joint surfaces but allows one to visualize and preserve these crucial volar ligaments.3–5 The arthroscopic procedure may carry less risk of injury to the superficial radial nerve branches, with less pain compared to an open procedure.

Indications

The indications for an arthroscopic radial styloidectomy are similar to the open procedure. Radial styloid impingement due to radioscaphoid arthritis is a common indication. This is often a consequence of long-standing scapholunate dissociation or end-stage Kienbock’s disease. Culp et al. suggest that patients who have painful radial deviation and a positive Watson test but have preserved wrist motion and good grip strength are ideal candidates.6 Chronic scaphoid nonunion, in which the hypertrophic distal scaphoid fragment impinges against the radial styloid during wrist radial deviation, is another common indication. If an attempt is made to internally fix the scaphoid, this impingement must be addressed. Resection of the distal scaphoid fragment will obviate the need for a radial styloidectomy.7

Secondary radial styloid impingement is a common sequella of a scaphotrapeziotrapezoidal (STT) fusion when it is used to treat rotary subluxation of the scaphoid or scaphotrapezialosteoarthritis (OA). Watson observed this in more than a third of his patients and now recommends a radial styloidectomy at the time of STT fusion.8 Impingement may also occur following a capitolunate fusion, which should be checked for at the time of surgery.9 Occasionally a limited styloidectomy is performed at the time of a proximal row carpectomy for treatment of radiocarpal OA.10

Contraindications

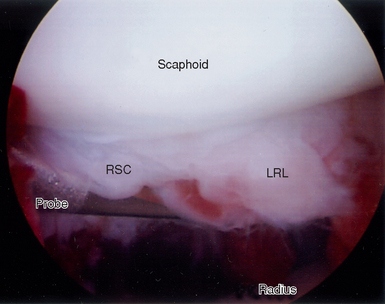

The main risk following a radial styloidectomy is ulnar translocation of the carpus. Siegal and Gelberman showed that short oblique osteotomies were the least destructive, whereas vertical oblique and horizontal osteotomies removed 92 to 95% of the radioscaphocapitate (RSC) ligament and 21 to 46% of the long radiolunate ligament (LRL).2 Cooney and coauthors emphasized the importance of the RSC and LRL ligaments in preventing ulnar translocation. If too much of these ligaments is removed, the capitate is destabilized and no longer rests in the lunate fossa—resulting in radial instability. Biomechanical testing revealed a significant increase in radial translation under loading when ≥6 mm or the radial styloid was excised.

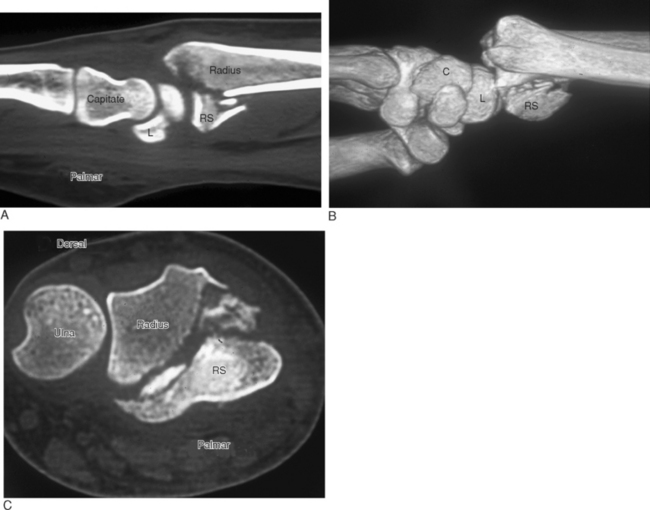

Some specimens demonstrated moderate to severe palmar and ulnar translation. They recommended limiting the bony resection to no more than 4 mm to minimize this risk.1 Patients who do not have an intact RSC ligament due to distal radius fracture11 (Figure 24.1a through c) or radiocarpal dislocation (Figure 24.2)12–14 are at risk for ulnar translocation and are not candidates for this procedure, especially if a proximal row carpectomy is contemplated.15 Ulnar translocation is a frequent sequella of long-standing rheumatoid disease. Hence, any patient with chronic wrist involvement is a poor candidate for this procedure.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree