11 The first known use of arthroscopy to treat osteoarthritis of the knee was reported in 1934 by Burman et al1 in their group of 11 patients. They remarked, “It was in a group of arthritic cases that we had the pleasant surprise of seeing a marked improvement in the joint following arthroscopy.” Haggart2 and Magnuson,3 a decade later, pioneered joint debridement of osteoarthritis using open arthrotomy. Haggart improved symptoms in 19 of 20 patients, whereas Magnuson touted “complete recovery” in 60 of 62. Both of these studies attribute improvement in symptoms to the removal of rough and irritating material. In 1950, Isserlin4 claimed success in 23 of 35 debridement arthrotomies, greatly reducing pain and achieving motion from nearly full extension to 90 degrees. With the advancement of arthroscopy during the 1970s, surgeons realized its diagnostic and therapeutic value without the morbidity associated with arthrotomy. Jackson and Abe5 demonstrated pain relief with debridement and also recognized the therapeutic value of irrigation. At the same time, O’Connor6 relieved symptoms of crystal-induced synovitis with arthroscopic lavage. Since that time, multiple studies have reported symptomatic relief in the arthritic patient following lavage and/or debridement of the knee.7–20 The procedure gained popularity because it is a relatively safe, palliative form of therapy, and according to Schonholtz,21 “no bridges are burned with arthroscopic surgery, [and] more extensive surgery can be carried out later.” This is of particular importance for the athlete, in whom a major reconstructive procedure may be the end of a favorite activity or even a career. The increasing awareness by the public of a presumed safe, rapid source of relief with minimal recovery period has driven demand for use of arthroscopy for this purpose. Although the literature on this subject is abundant, only a minority of studies is prospective or controlled.22–26 Other studies have been less enthusiastic, criticizing the study designs and the paucity of evidence demonstrating change in the course of disease.27–29 A recent randomized, prospective, placebo-control study30 has renewed orthopaedists’ and the public’s interest in closely examining this procedure from both a medical and an economic standpoint. This chapter defines the various modalities of arthroscopic debridement, describes the physiologic changes, and reviews the literature of outcomes for these procedures. As with any procedure, appropriate patient selection is important to a successful outcome. Generally, the indications for arthroscopic debridement in athletes are patients who have failed previous nonoperative management including rest, physical therapy, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications, and steroid injections. No standard algorithm exists for the timing of surgery, and the optimal age groups varies in reported studies.31,32 To our knowledge, no study reports on the success of this operation in the isolated athletic patient group. Age alone is not a reliable predictor of successful treatment.33 Jackson and Rouse34 reported on 68 patients over 40 years of age treated with partial arthroscopic meniscectomy and found that age did not effect the outcome. Lotke et al10 concluded that traumatic meniscal tears treated with debridement might do well regardless of the patient’s age. In Insall’s33 review of the Pridie resurfacing technique, he stressed that the ideal patient was middle-aged and active, rather than the elderly who may be incapable of postoperative rehabilitation. This contradicts Burks’s35 review of the arthroscopy literature, which showed that the elderly benefit most from lavage, probably due to their lower level of activity. The duration of symptoms is an indicator of how much the patients will improve following arthroscopic debridement. Baumgaertner et al8 stated that symptoms of less than 12 months’ duration significantly predicted better outcome, as did Lotke.10 Wouters36 showed that pain of less than 3 months’ duration, a history of twisting injury, or locking was a significant predictor of a better postoperative outcome. Malalignment is repeatedly blamed for poor results following arthroscopy.8,36 Harwin37 showed that patients with malalignment greater than 5 degrees had only 26% satisfactory results by subjective measurements compared with 84% of patient with normal alignment. Salisbury et al38 concluded that patients with malalignment “should be excluded from consideration for arthroscopic debridement.” Younger patients with varus knees are better served by undergoing high tibial osteotomy.38,39 Arthroscopy is not a substitute for a definitive reconstructive procedure in a young athlete with varus deformity.28 Patients who have laxity due to ligamentous insufficiency also do poorly. Radiographic findings such as large osteophytes and loose bodies indicate that the patient will not see much improvement. Severity of arthritis is a prognostic indicator for the success of arthroscopic debridement.8,36,40 A complete loss of joint space, as opposed to minor narrowing, is a poor prognostic indicator. Aichroth7 showed significantly better results in patients with Outerbridge41 stage I and II knees versus stage III and IV. Looking at preoperative radiographs, Lotke10 found that patients with normal radiographs had a 90% chance of good to excellent symptom relief following a medial meniscectomy versus only a 21% chance of similar results if the patient showed moderate to marked arthritic changes. In Baumgaertner et al’s8 study, 77% of patients with mild or moderate changes on x-rays had a good to excellent result, according to a grading system of pain, function, and patient enthusiasm, versus 33% with severe changes.

Arthroscopic Management of the Early Arthritic Joint

STEVEN S. GOLDBERG, RAFFY MIRZAYAN, AND C. THOMAS VANGSNESS, JR.

Indications

Indications

| Positive | Negative | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal alignment | Malalignment >5 degrees | |

| Minimal radiographic changes | Radiographic signs of osteoarthritis | |

| Symptoms <3 months | Symptoms >1 year | |

| Mechanical symptoms | Pending litigation | |

| Flap tears | Degenerative tears | |

| Isolated medial femoral condyle lesions | Diffuse chondromalacia |

Patients who are filing workman’s compensation claims or are in the process of litigation also tend to do poorly.

Novak and Bach39 summarized the factors predicting a better outcome in their study. These factors included normal alignment, a history of mechanical symptoms, minimal roentgenographic degeneration, and a short duration of symptoms. Table 11–1 lists predictors of outcome summarized from several studies on arthroscopic debridement.

Overview of Orthoscopic Choices

Overview of Orthoscopic Choices

Arthroscopic debridement can generally be divided into three categories, in order of increasing alteration of the native tissue: (1) lavage, (2) debridement, and (3) abrasion arthroplasty.

Arthroscopic lavage involves washing the knee with fluid, usually lactated Ringer’s solution or saline. The mechanism of benefit of lavage is thought to be the removal of prostaglandins,42 enzymes,43 crystals,6 and cartilaginous debris,44 mechanically loosened from the surfaces.

Debridement includes removal of loose bodies, osteophytes, and fibrillated chondral flaps of roughened articular and meniscal cartilage to create smooth cartilage surfaces using a motorized shaver. The irritants that stimulate the synovial lining of the joint are reduced, which in turn decreases joint effusions, and proteolytic enzymes.

Abrasion arthroplasty involves scraping the articular surface 1 to 2 mm until bleeding bone is encountered.45Techniques that penetrate the subchondral bone are not considered arthroscopic debridement and are discussed in other chapters.

Surgical Debridement Technique

Surgical Debridement Technique

Arthroscopy is performed through the standard anteromedial and anterolateral portals and occasionally a third, superomedial portal. A systematic diagnostic examination of the joint is performed, including inspection for loose bodies in the suprapatellar pouch, medial and lateral gutters, and the popliteus hiatus. The Gillquist views are used to evaluate the posterior joint for loose bodies.46 The posteromedial compartment can be visualized by placing the arthroscope between the posterior cruciate ligament and medial femoral condyle from the lateral portal. The posterolateral compartment can be visualized by placing the arthroscope between the anterior cruciate ligament and the lateral femoral condyle from the anteromedial portal.

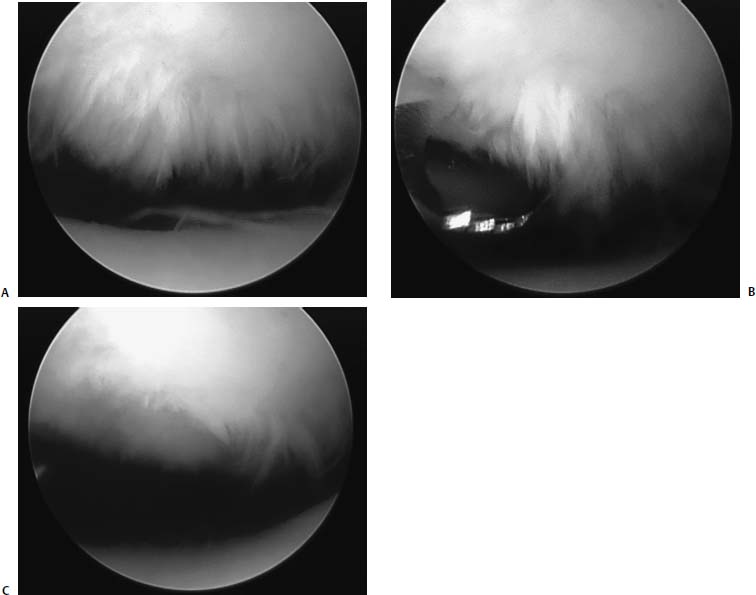

FIGURE 11–1 (A) “Crab meat” appearance on the undersurface of the patella. (B) The shaver is used in the “fast-forward” mode, instead of oscillate mode to debride the worn cartilage. (C) Final appearance of patella after debridement.

The cartilaginous surfaces of the joint are graded based on the Outerbridge41 classification. A probe is inserted and the cartilaginous surfaces are palpated. Loose flaps of cartilage are elevated and the extent of delamination is evaluated. The menisci are evaluated as well with a probe and their stability is assessed. A motorized shaver can be used to debride loose flaps of cartilage with variable results. For example, when the cartilage is softened and has a “crab meat” appearance (Fig. 11–1), the shaver can be used to remove the abnormal cartilage and smooth down the articular surface. This is much easier to accomplish if the shaver is used in the “fast forward” mode instead of the “oscillate” mode. Degenerated menisci with flap tears are first debrided with an arthroscopic basket or shaver, and then smoothed to provide a smooth transition with the remaining horns of the meniscus. Radiofrequency devices on the articular cartilage are not recommended. The knee is then thoroughly irrigated and massaged to remove any remaining loose debris. Once the wounds are closed, a soft compressive dressing is applied. Patients are permitted to bear weight as tolerated but activities are limited until the sutures are removed 7 to 10 days later. Athletes usually return to sports when pain and swelling is controlled, and when muscle strength is equal to the contralateral limb.

Published Results

Published Results

Lavage

Arthroscopic lavage has been proposed as a treatment for osteoarthritis since Burman1 published his first results in 1934. Since that time, several authors have supported the use of lavage.47,48,49 Livesley et al23 prospectively compared patients with physiotherapy to patients with arthroscopic lavage plus physiotherapy. They found that the lavage patients had a significant overall relief of pain for up to 1 year and that signs of inflammation were significantly better for up to 3 months when looking at joint tenderness, warmth, morning stiffness, swelling, and disturbance in the patient’s sleep pattern. Edelson et al47 retrospectively reported that knee washout resulted in good or excellent pain relief and functional improvement in 86% of patients at 1 year and 81% of patients at 2 years. This study did not have a control group, and the author stated in the discussion “it is possible that some placebo effect may have contributed to the perceived benefit.” Eriksson and Haggmark48 reported on 10 runners who improved with arthroscopy and continued to be able to run with repeat needle lavage every 4 to 12 months.

Other studies have not been as supportive of the benefits. Bird and Ring’s50 percentage of patients with improvement dropped from 93% to 50% between postoperative week 1 and week 4. Using infrared thermography, a quantifiable measurement of inflammation showed no significant changes in unoperated knees. Lindsay et al’s22 prospective, double-blind controlled study found no additional benefit to synovial irrigation when compared with needle aspiration.

Arthroscopic Debridement

Haggart2 and Magnusson3 first reported debridements of arthritic knees with arthrotomy in 1940 and 1941, and in the 1970s, Jackson and Abe5 advanced the technique by employing the arthroscope for the same procedure. Sprague51 published an early report of arthroscopic debridement of a degenerative knee. In his study, 62 patients were followed for an average of 13 months and 74% had good results, as determined by a patient’s subjective assessment of improvement compared with before surgery. Because of the limited morbidity and good results, Sprague stated, “arthroscopic debridement of the knee joint is recommended as a useful therapeutic modality in many patients with degenerative arthritis of the knee.” Since that time there have been multiple reports of the beneficial effects of arthroscopic debridement for osteoarthritis.20

Despite good initial results only a small number of studies have evaluated the beneficial effects over time. Jackson19 achieved symptom improvement in 68% of patients at 3 years, Timoney et al17 in 63% at 4 years, and Bert and Maschka16 in 66% at a minimum of 5 years. But in Baumgaertner et al’s8 retrospective study of patients over 50 years of age, only 40% of patients maintained good or excellent results through the 33-month follow-up.

McLaren et al15 retrospectively reviewed 171 patients ranging in age from 23 to 82 years undergoing arthroscopic debridement, and although 65% of the patients felt their symptoms were improved, there was no identifiable trend with respect to age, severity of disease preoperatively or witnessed during surgery, alignment, or presence of osteophytes. The authors noted that improvement in symptoms is “marked, but unpredictable.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree