In comparison with anterior shoulder instability, posterior instability is uncommon, occurring in 2% to 10% of cases, and covering a wide clinical spectrum ranging from locked posterior dislocation to the often subclinical recurrent posterior subluxation (RPS). With increased clinical awareness, imaging advances such as magnetic resonance arthrography, and the development of specific provocative physical examination tests, the identification of RPS in the athletic population is improving. This article describes the anatomic-based arthroscopic approach to treatment of RPS, which allows for enhanced identification and repair of intra-articular pathology including posterior capsular laxity, complete or incomplete detachment of the posterior capsulolabral complex, and inferior capsular tears. While postoperative results are generally good to excellent after stabilization for RPS, there is room for improvement.

In comparison with anterior shoulder instability, posterior instability is uncommon, occurring in 2% to 10% of cases. A posteriorly directed blow to an adducted, internally rotated, and forward-flexed upper extremity is classically described as the sentinel traumatic event. However, recurrent or locked posterior shoulder dislocations from macrotrauma are exceedingly rare in the athletic population. Instead, athletes typically present with posterior shoulder instability secondary to repetitive microtrauma, which can occur in multiple arm positions and under a variety of loading conditions. In 1952, McLaughlin first acknowledged the existence of a wide clinical spectrum of posterior shoulder instability, ranging from locked posterior dislocation to the often subclinical recurrent posterior subluxation (RPS).

In athletics, RPS has been observed in weightlifters, football linemen, golfers, tennis players, butterfly and freestyle swimmers, overhead throwers, and baseball hitters, among others. The origin of RPS is repetitive microtrauma, most commonly leading to posterior capsular attenuation and labral tearing. Regardless of the sport, athletes with RPS typically present with ambiguous complaints of diffuse pain and shoulder fatigue, without distinct injury, often making it challenging to elucidate the underlying pathology and diagnosis.

A thorough history and physical examination, coupled with specific imaging studies, are required to determine the exact pathogenesis of and appropriate treatment options for RPS. With increased clinical awareness, imaging advances such as magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA), and the development of specific provocative physical examination tests, the identification of RPS in the athletic population is improving. Several variables that must be considered during the workup include mechanism of injury (true posterior traumatic dislocation vs repetitive microtrauma vs an acute on chronic subluxation), specific direction of instability (posterior vs posteroinferior or posterosuperior), and the pattern of instability (unidirectional or multidirectional), as these factors will ultimately affect treatment and outcome.

Successful treatment of RPS begins with thorough identification of all of the structural abnormalities present in the affected shoulder, which can include any combination of the labrum, capsule, supporting ligaments, and rotator cuff. Over time, posterior glenohumeral stabilization has evolved from various open procedures to an anatomic-based arthroscopic approach, which allows for enhanced identification and repair of intra-articular pathology including posterior capsular laxity, complete or incomplete detachment of the posterior capsulolabral complex, and inferior capsular tears. While postoperative results are generally good to excellent after stabilization for RPS, there is room for improvement. Accordingly, research continues on both the biomechanical and clinical fronts to further refine diagnostic and treatment approaches to RPS.

Pathoanatomy

The pathogenesis of RPS varies among athletes, in direct relationship to the particular repetitive stresses placed on the posterior structures of the glenohumeral joint during competition and training. For example, activities like push-ups, bench-press weight lifting, and blocking in football linemen all place direct stress on the posterior capsulolabral complex of the shoulder, potentially resulting in RPS. Similarly, the follow-through phase of throwing, pull-through phase in swimming, tennis backhand stroke, and golf backswing can all lead to RPS.

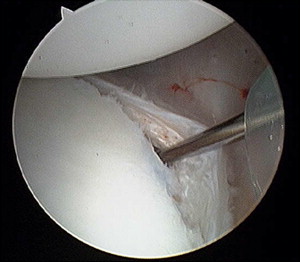

The posterior labrum, capsule, and posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL) are the primary stabilizers to posterior translation of the humeral head, particularly between 45° and 90° of glenohumeral abduction. The posterior capsule is delineated by the area between the intra-articular portion of the biceps tendon and the posterior band of the IGHL. The posterior capsule is the thinnest segment of the shoulder capsule, devoid of any supporting ligamentous structures, thus making it prone to attenuation from applied stress. It has been postulated that overhead throwers, tennis players, and swimmers develop shoulder pain associated with progressive laxity of the posterior capsule and fatigue of the static and dynamic stabilizers. Recurrent posterior subluxation can lead to plastic deformation of the posterior capsule, and a patulous posteroinferior capsular pouch with an associated increased joint volume. After a traumatic posterior subluxation or dislocation, athletes may sustain a capsulolabral detachment known as a reverse Bankart tear, further contributing to recurrent instability and symptoms ( Figs. 1 and 2 ).