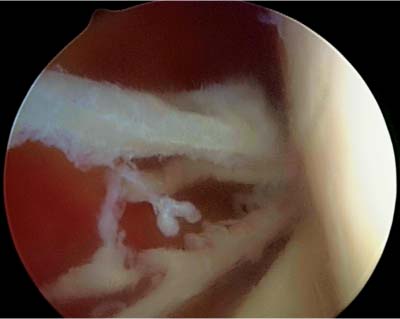

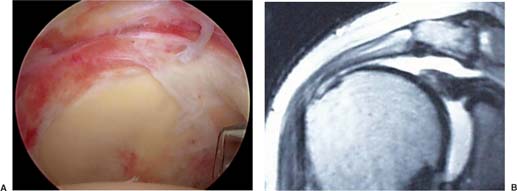

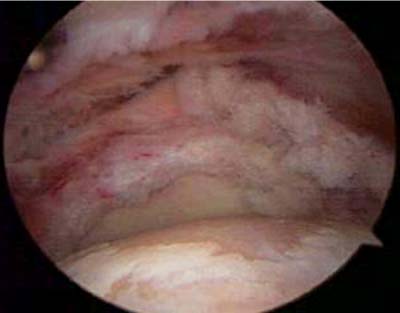

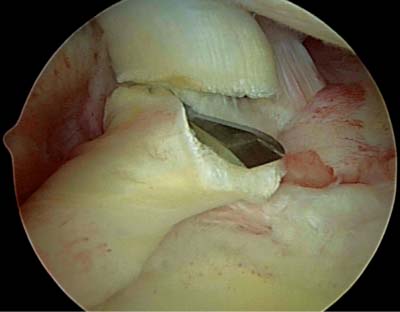

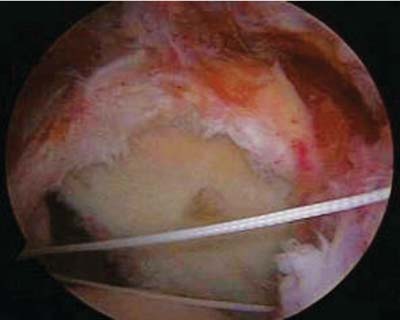

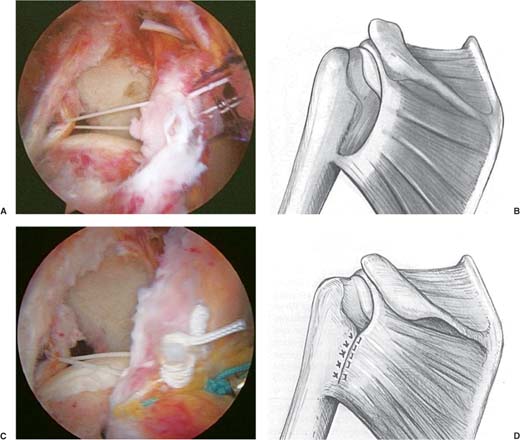

4 Arthroscopic Management of Massive Rotator Cuff Tears Since Watanabe and the early days of arthroscopy, arthroscopists have been pushing the envelope to see just how far minimally invasive techniques can go. The primary goal has always remained the same, “To do the most good with the least amount of harm to surrounding tissues.” With the development of smaller instruments, better cameras, and standard techniques, the evolution has progressed steadily in the knee with the shoulder now just coming into its own. Arthroscopic repair of small to large cuff tears has been achieved, and now some massive tears are being addressed as well.1–6 Indications include patients that are able to lift their arm overhead with some difficulty and have a chief complaint of significant pain rather than weakness. Treatment options range from less complex procedures to state-of-the-art bioengineered implants. They include débridement of the rotator cuff (RC) in isolation, biceps tenotomy or tenodesis, partial repair of the RC tendons, cuff mobilization by interval slides with subsequent repair, soft tissue patch tenodesis, and soft tissue patch augmentation for cuff deficiency. The goal of treatment is to relieve pain and therefore improve function. If there is significant muscle atrophy at the time of initial evaluation, then permanent weakness is to be expected irrespective of the treatment chosen. This must be conveyed to the patient preoperatively so their expectations before surgery are realistic. Repair may work best in patients that have slight narrowing of the acromiohumeral distance (Fig. 4–1). A contraindication to arthroscopic repair of massive cuff tears is the condition where the acromiohumeral distance is significantly narrowed secondarily to arthritis. Cuff arthropathy (Fig. 4–2) should be more properly addressed with a shoulder arthroplasty and is beyond the scope of this chapter. RC tears by definition are defined as small (<1 cm), medium (1 to 3 cm), large (3 to 5 cm), and massive (>5 cm).2,3 Further classifications have considered massive tears as any tear that involves two or more tendons (Fig. 4–3).4 The authors consider massive tears as a tear of the supraspinatus tendon that either then extends posteriorly into the infraspinatus tendon or extends anteriorly traversing the rotator interval and involving the subscapularis tendon insertion (Fig. 4–4). When the latter exists, the biceps tendon is frequently partially torn or dislocated from the intertubercular groove. The patient with a massive tear of the RC usually presents with complaints related to pain and loss of function. Pain may vary from none to a significant amount. Night pain is often seen when the patient lies on the unaffected side, with some relief gained by lying on the affected arm. Comorbidities frequently exist with this patient population. The patients tend to be older, have a high BMI, suffer from heart disease, and frequently have a workmen’s compensation claim pending. Other comorbidities include female gender, long duration of symptoms (>3 years), and a poor anesthetic classification (America Society of Anesthesiologists).5–12 Figure 4–1 Narrowed rotator interval on the “push-up” radiographic view. Figure 4–2 Rotator cuff arthropathy, a contraindication for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Figure 4–3 Arthroscopic intra-articular view upon introduction of the scope from the posterior portal. On clinical examination stiffness may predominate with radiographic evidence of superior humeral head migration and arthritic changes. For patients that present primarily with pain, they may have a full range of motion and be able to lift their arm overhead even though they have weakness with resisted external rotation as seen with a positive belly-off test.6–15 Overhead function can exist because the remaining cuff muscles are able to center the humeral head near the glenoid so that the deltoid and other muscles can function satisfactorily to lift the arm overhead. Some patients, preoperatively, can lift their arm overhead by trapping the humerus under the acromion; this is the so-called awning effect described by Burkhart.7,8 The surgeon needs to discuss with the patient the success for pain relief and functional recovery to establish reasonable postoperative expectations. If the surgical procedure is able to center the humeral head within the glenoid, even if the muscle is not intact, then recovery of overhead function is a significant possibility. A discussion with the patient about surgery should begin with the concept that the arthroscope can be used to evaluate the shoulder’s pathology and outline the overall treatment plan. The discussion then involves the range of treatment from simple débridement, to partial or complete repair, to the use of tissue patches for repair augmentation.9 The patients are informed that pain relief is typically achieved, but functional weakness can still persist. Additionally, the patients are informed that on postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound there generally is not complete evidence of cuff healing.10 Figure 4–4 (A) Arthroscopic view from the subacromial space with the scope in the lateral portal. Note the absence of infraspinatus and supraspinatus with tear extension into the rotator interval. (B) Shoulder magnetic resonance imaging scan of a patient with a massive rotator cuff tear. MRI studies are useful in determining the size of a rotator cuff tear and indicating whether it is partial or full thickness (Fig. 4–4). Additionally, they aid in determining the amount of fatty infiltration present within the involved muscles. An MRI cannot predict ease of mobilization of the torn tendons in preparation for repair nor can it predict postoperative patient function. The Goutallier scale provides a useful method for quantifying the amount of fatty infiltration of the muscle. The fatty infiltration can vary from 0 (no fat), 1 (some fat), 2 (more muscle than fat), 3 (muscle equal to fat), and 4 (less muscle than fat).11 The amount of fatty infiltration of the muscle does not decrease with surgery; this has been shown both in clinical studies as well as in animal models. Goutallier has created a global fatty regeneration index (GFDI), which is the total amount of fat in the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis muscles combined.11 In Goutallier’s study, the percentage of recurrence after open cuff repair was related to the amount of fat within the muscle, where repaired cuffs were more likely to retear if their preoperative fatty infiltration was high. The suprascapular nerve with its sling affect under the transverse scapular ligament is another factor involved in cuff atrophy and its ultimate recovery. Some authors have reported improvement after release of the suprascapular nerve by documenting preoperative and postoperative decompression EMG studies.12 Release of the suprascapular nerve may have a role in the future in the arthroscopic treatment of rotator cuff tears. Diagnostic arthroscopy of the glenohumeral joint and subacromial space allows the surgeon to evaluate the RC and make a decision as to whether débridement without repair13 or débridement with partial or complete repair can easily be done, and whether or not advanced techniques such as interval releases will be necessary. The biceps tendon can be débrided and released (tenotomy) or tenodesed. The articular cartilage and labrum can be débrided and any loose bodies removed. A subacromial bursectomy with limited subacromial decompression will allow for bursal-sided cuff visualization in preparation for repair. Of particular importance is the preservation of the coracoacromial ligament and anterior bone of the acromion. The most severe complication seen after aggressive release of the coracoacromial ligament and resection of the anterior subacromial bone is a disastrous migration superiorly of the humeral head followed by the patient’s inability to lift his or her arm overhead. An 81-year-old man complained of pain with activity; he was able to elevate his arm forward to 120 degrees. In qualifying his distress, the patient stated that 80% of his problem was pain and 20% was loss of function. An MRI scan showed the humeral head to be superiorly migrated on the glenoid with abutment against the undersurface of the acromion (Fig. 4–5). His RC was retracted to the superior margin of the glenoid rim. There was significant atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscle. An arthroscopy was performed and demonstrated a massive RC tear with bare bone exposed on the humeral head (Fig. 4–6). His humeral head was congruent. Treatment consisted solely of a biceps tenotomy with a banana knife blade for his dislocated biceps (Fig. 4–7). Five years later, the patient was satisfied with minimal pain and an ability to lift his arm to 120 degrees of forward elevation. Figure 4–5 Shoulder magnetic resonance imaging scan of an 81-year-old man with a chief complaint of pain. Figure 4–6 Arthroscopic image of a massive tear with a dislocated biceps tendon. Patients in which a complete repair of a massive cuff tear is not possible usually can lift their arm overhead to 150 degrees, preoperatively. They tend to have external rotation weakness and pain as a chief complaint. Often the supraspinatus tendon is retracted well medial to the glenoid rim and atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles is quite marked. In these patients, a partial repair is usually feasible and quite satisfactory.14 An illustration of this is a 75-year-old woman who enjoys daily swimming. Clinically, she was able to elevate her arm 150 degrees, with weak external rotation and marked pain. Her MRI revealed an elevated humeral head with medial retraction of the supraspinatus past the glenoid (Fig. 4–8). At surgery, mobilization of the supraspinatus tendon laterally was unsuccessful, but advancement of the infraspinatus tendon anteriorly into the supraspinatus footprint was achieved. The infraspinatus was then successfully repaired with suture anchors (Fig. 4–9). Burkhart has nicely illustrated this concept of a partial repair of the infraspinatus, with advancement toward the anterior, in patients with a massive tear that is complete and retracted (Fig. 4–10).15 Figure 4–7 Arthroscopic biceps tenotomy with a banana blade. Figure 4–8 Magnetic resonance imaging scan of a 75-year-old woman with a chief complaint of pain. The initial arthroscopic evaluation of the RC begins with the creation of a posterior lateral and anterior portal followed by a lateral portal (Fig. 4–11). The anterior portal is placed lateral to the coracoacromial ligament to allow for easy scope movement and to preserve the coracoacromial ligament. The shaver is used to excise the subdeltoid bursa. The initial procedure begins with the scope posterior and the shaver anterior to allow for débridement of the bursa followed by the RC tendon and the cuff footprint on the greater tuberosity (Fig. 4–12). The lateral border of the greater tuberosity should be defined. Close inspection for the medial extent of the supraspinatus tendon should be performed. When found, its mobility should be determined with the use of an arthroscopic grasper (Fig. 4–13). Figure 4–9 Arthroscopic image of a partial repair of a three tendon rotator cuff tear. Figure 4–10 (A) Arthroscopic image of a partial repair of the infraspinatus tendon into the supraspinatus footprint and (B) artist’s rendering, (C) final appearance after knot tying and (D) artist’s rendering. The aggressive excision of the coracoacromial arch with its coracoacromial ligament strut should be avoided. Instead, a simple subacromial bursectomy with “smoothening” of the undersurface of the acromion can be employed as described by Matsen.16 This allows for excellent cuff visualization, while preserving the function of the arch and eliminating potential causes of impingement. The arthroscope is then moved to the lateral portal and débridement of the bursa from posterior, along the infra-spinatus tendon, is performed. During this process, the bursa can be traced laterally to the deltoid insertion and the infraspinatus insertion on the greater tuberosity can be defined (Fig. 4–14). The shaver can then be used on the undersurface of the acromion further excising the bursa and allowing for complete delineation of the supraspinatus muscle. The bony undersurface of the acromion is not excised, but rather is cleaned and followed down to the spine of the scapula, which will later be used to outline “the posterior cuff interval” between the supraspinatus and the infraspinatus tendons (Fig. 4–15). The shaver is then placed in the anterior portal; while preserving the coracoacromial ligament, the bursa is excised inferior to the ligament down to the level of the coracoid. This allows for exposure of the coracohumeral ligament (CHL).

Definition of a Massive Rotator Cuff Tear

Patient Presentation

Diagnostic Evaluation

Treatment

Arthroscopic Approach

Arthroscopic Débridement with Biceps Tenotomy

Cleaning–up of Large Rotator Cuff Tears

Anterior Advancement of the Infraspinatus

Partial Repair of Large Rotator Cuff Tears

Surgical Technique

Initial Arthroscopic Evaluation of the Rotator Cuff

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree