Although soft tissue stabilization procedures in the shoulder yield good results, arthroscopy and radiological investigations have identified more complex soft tissue and bony lesions that can be successfully treated using a Latarjet procedure. The authors have advanced this technique to make it possible arthroscopically, thereby conferring all the benefits that arthroscopic surgery offers. This article describes how and why the arthroscopic Latarjet procedure is a valuable tool in the treatment of complex shoulder instability and how the procedure can be introduced into practice. This technique has shown excellent results at short- to mid-term follow-up, with minimal complications. As such, this procedure is recommended to surgeons with good anatomic knowledge, advanced arthroscopic skills, and familiarity with the instrumentation.

The increase in popularity of arthroscopic shoulder surgery in the past 20 years has led to an expansion in the operative treatment options available for shoulder instability. This in part can be explained by the arthroscopic exposure given to a new generation of shoulder surgeons throughout residency and fellowship training, and the enthusiasm with which many open surgeons have pioneered and embraced stabilizing techniques. In addition, the added scrutiny of the shoulder afforded by the use of the arthroscope has led to an improved understanding of previously unrecognized soft tissue lesions underlying many cases of instability. The role of glenoid and humeral head bone defects in recurrent instability has also been better appreciated arthroscopically, especially when these lesions are evaluated in combination with preoperative radiological studies.

Despite advances in techniques and instruments, and improvements in surgical training, there still remains a significant failure rate when stabilization procedures inadequately address the underlying pathology. The open Latarjet procedure has shown excellent and reliable results in the recent literature. The natural evolution of this procedure is an all-arthroscopic technique to confer all of the advantages of the open procedure while using a minimally invasive technique.

Is there a need for the arthroscopic Latarjet procedure?

Most shoulder surgeons are familiar with either an arthroscopic or open Bankart repair for recurrent shoulder instability largely because a capsulolabral avulsion from the glenoid rim is the most common lesion associated with shoulder dislocations. This technique has demonstrated excellent results when used to treat isolated soft tissue Bankart lesions. However, a problem emerges when this form of repair is used in patients who have more extensive soft tissue injuries such as complex labral disruptions, capsular attenuation, or humeral avulsion of glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) lesions. In these cases, reducing the labrum back on to the anterior glenoid is often not sufficient to restore shoulder stability, particularly when the labral tissue is no longer functional or there is a capsular detachment on the humeral side.

Inferior results have also been associated with a capsulolabral repair when it is used in cases where bony deficiency is a major contributing factor to the recurrent instability. This concern has been raised by many investigators after several years of follow-up, particularly with regard to young patients (<20 years) and those involved in overhead or contact sports. In 2006, Boileau and colleagues reviewed 91 consecutive patients who had undergone Bankart repairs for anterior shoulder instability, and found a 15.3% recurrence rate. The cause for recurrence was most commonly bone loss on the glenoid, bone loss on the humeral head, or inferior ligament hyperlaxity (as indicated by an asymmetric hyperabduction test). A combination of these abnormalities can result in up to 75% recurrence of instability after soft tissue repair, because the repair does not restore the glenoid articular arc that is reduced secondary to the glenoid bone loss or the engaging Hill-Sachs lesion.

There is an apparent need for an alternative surgical strategy to a standard Bankart repair to restore stability when the glenohumeral ligaments are torn or attenuated in combination with glenoid bone loss or an engaging Hill-Sachs lesion.

When to consider the Latarjet procedure

All patients undergo a detailed history and clinical examination followed by radiography (including a Bernageau view) or computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies. This process usually identifies clinical situations in which a capsulolabral repair is thought to be insufficient and therefore a Latarjet procedure is believed to be superior. However, the situation can arise when the need for a Latarjet procedure becomes apparent only on initial arthroscopic inspection. For this reason it is necessary to consent patients accordingly.

The arthroscopic Latarjet procedure is considered in the following situations.

Complex Soft Tissue Injuries

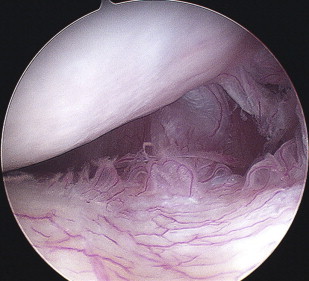

Improvements in radiological investigations, especially when radiopaque dyes are used, has led to enhanced identification of HAGL lesions on preoperative CT or MRI scans. However, it is common to detect these lesions for the first time on arthroscopic inspection ( Fig. 1 ). Multiple techniques are described for the arthroscopic repair of HAGL lesions, and most of these include only small case series with short follow-up periods. The authors’ experience using an all-arthroscopic soft tissue repair technique with anchors was disappointing because of postoperative stiffness experienced by some patients.

Where patients have had multiple dislocations, the intrinsic structure of the glenohumeral ligaments is usually found deranged, although this may not be evident macroscopically. Simply reopposing this damaged tissue back to the glenoid does not necessarily restore stability to the shoulder. This practice has been likened to rehanging a baggy or incompetent hammock.

A further soft tissue injury is that of the irreparable labrum, especially in which there has been a complete radial tear thereby effectively breaking the ring. A repair of the labrum in this situation rarely provides sufficient strength of healing to restore stability.

In these situations, reattaching or repairing these structures leads to a suboptimal outcome either through stiffness or recurrence, and as such a Latarjet procedure would be performed.

Bony Defects

Glenoid bone loss

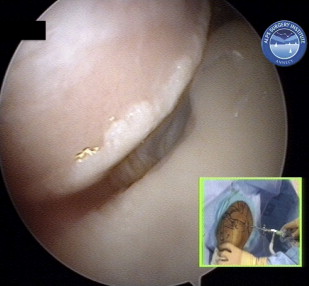

Glenoid bone loss as the cause for recurrent instability is frequently overlooked but is usually manifested by an avulsion type bony Bankart lesion, an impacted fracture, or erosion of the anteroinferior glenoid rim. Radiographs may show a fracture or a more subtle loss of contour of the anteroinferior glenoid rim. A decrease in the apparent density of the inferior glenoid line often signifies an erosion of the glenoid rim between the 3- and 6-o’clock position. An axillary or Bernageau view may show flattening of this area of the glenoid when bone loss has occurred. CT provides a more detailed imaging modality, which is essential to quantify the bone loss preoperatively. CT reconstructions also provide a more robust static measurement than those afforded by the arthroscopic view ( Fig. 2 ).

The amount of glenoid bone loss can be assessed during preoperative evaluation or surgery. With adequate imaging, bone loss can be determined with the Bernageau view, sagittal and oblique CT scans, and 3-dimensional reconstructions. In addition, the amount of glenoid bone loss can be verified arthroscopically by measuring the distance from the glenoid rim to the bare spot, thereby assisting the surgeon in identifying an inverted pear glenoid, and confirming substantial bone loss and the likely failure of an isolated soft tissue repair. The threshold beyond which a soft tissue repair is likely to fail is difficult to define, and significantly increased glenohumeral instability has been suggested with defects anywhere between 21% and 28.8% of the glenoid (although caution should be exercised when comparing measurement methods).

Even when the bony fragment is present, replacing it is not always sufficient to restore the bony glenoid articular arc, especially when recurrent episodes of instability have further eroded the remaining glenoid edge. There are also issues regarding healing in this potentially necrotic bone. In these cases a bony reconstruction should be considered.

Humeral bone loss

The location and size of the Hill-Sachs lesion determines the degree to which the articular arc is reduced and when the lesion will engage on the glenoid. Dynamic arthroscopy with the shoulder in abduction and external rotation will demonstrate whether the lesion will engage during a functional or athletic overhead range of movement. To reduce the chances of recurrence, the articular arc must be increased to prevent early engagement of the lesion on the glenoid rim when the arm is externally rotated; this can be achieved with the use of a bone block procedure. An alternative to this would be the “remplissage” procedure as described by Purchase and colleagues (suturing of the infraspinatus and posterior capsule into the defect).

By enlarging the glenoid articular arc with a bone graft, the joint surface contact areas are increased and therefore the joint surface contact pressures are reduced during external rotation. The remplissage procedure does not alter the joint contact surface areas or increase the articular arc, and therefore has no effect on reducing the joint contact pressures, which may then have an effect on the development of future arthrosis. Advancing the infraspinatus and capsule into the humeral bony defect can also significantly decrease the amount of external rotation the patient may be able to achieve postoperatively.

Combinations of glenoid and humeral bone loss

These 2 lesions usually occur in tandem with varying degrees of severity. Preoperative radiographs ( Fig. 3 ) and CT scans usually identify these lesions, but an arthroscopic dynamic evaluation of stability is necessary to determine the likely clinical effects of this combination ( Fig. 4 ). The presence of an engaging Hill-Sachs lesion coexisting with a glenoid bone defect markedly reduces the defect size threshold at which recurrence will occur if the patient had only one soft tissue or bony defect in isolation. Latarjet procedure is found to be appropriate to address the abnormal anatomy.

Revision Surgery for Instability

If the initial stabilizing procedure fails because of any of the reasons mentioned earlier, then a Latarjet procedure is ideally suited to restore stability. However, a second group of patients were observed who had seemingly successful Bankart repairs but went on to develop postoperative recurrent instability after 5 to 7 years. In this particular group, the soft tissue stabilization was adequate to return the patient to a sedentary lifestyle but it had not restored satisfactory stability for more active and sporting pastimes. This finding can in part explain the excellent results seen in series with a short follow-up. In these cases, although the initial operation was considered successful, the pathologic lesion was never truly corrected and the glenoid subsequently became increasingly eroded. These patients can be effectively managed with a Latarjet as well.

Patient Activity

Many patients now demand a quicker return to sports or their occupation, or they have a high risk of recurrence. This is particularly true for patients involved in collision sports (eg, rugby), overhead sports (eg, climbing), throwing sports, and high-demand physical overhead occupations (eg, carpentry). The ability to recreate a stable shoulder with a reduced rehabilitation time to return to full activity is another advantage of the arthroscopic Latarjet technique.

When to consider the Latarjet procedure

All patients undergo a detailed history and clinical examination followed by radiography (including a Bernageau view) or computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies. This process usually identifies clinical situations in which a capsulolabral repair is thought to be insufficient and therefore a Latarjet procedure is believed to be superior. However, the situation can arise when the need for a Latarjet procedure becomes apparent only on initial arthroscopic inspection. For this reason it is necessary to consent patients accordingly.

The arthroscopic Latarjet procedure is considered in the following situations.

Complex Soft Tissue Injuries

Improvements in radiological investigations, especially when radiopaque dyes are used, has led to enhanced identification of HAGL lesions on preoperative CT or MRI scans. However, it is common to detect these lesions for the first time on arthroscopic inspection ( Fig. 1 ). Multiple techniques are described for the arthroscopic repair of HAGL lesions, and most of these include only small case series with short follow-up periods. The authors’ experience using an all-arthroscopic soft tissue repair technique with anchors was disappointing because of postoperative stiffness experienced by some patients.

Where patients have had multiple dislocations, the intrinsic structure of the glenohumeral ligaments is usually found deranged, although this may not be evident macroscopically. Simply reopposing this damaged tissue back to the glenoid does not necessarily restore stability to the shoulder. This practice has been likened to rehanging a baggy or incompetent hammock.

A further soft tissue injury is that of the irreparable labrum, especially in which there has been a complete radial tear thereby effectively breaking the ring. A repair of the labrum in this situation rarely provides sufficient strength of healing to restore stability.

In these situations, reattaching or repairing these structures leads to a suboptimal outcome either through stiffness or recurrence, and as such a Latarjet procedure would be performed.

Bony Defects

Glenoid bone loss

Glenoid bone loss as the cause for recurrent instability is frequently overlooked but is usually manifested by an avulsion type bony Bankart lesion, an impacted fracture, or erosion of the anteroinferior glenoid rim. Radiographs may show a fracture or a more subtle loss of contour of the anteroinferior glenoid rim. A decrease in the apparent density of the inferior glenoid line often signifies an erosion of the glenoid rim between the 3- and 6-o’clock position. An axillary or Bernageau view may show flattening of this area of the glenoid when bone loss has occurred. CT provides a more detailed imaging modality, which is essential to quantify the bone loss preoperatively. CT reconstructions also provide a more robust static measurement than those afforded by the arthroscopic view ( Fig. 2 ).

The amount of glenoid bone loss can be assessed during preoperative evaluation or surgery. With adequate imaging, bone loss can be determined with the Bernageau view, sagittal and oblique CT scans, and 3-dimensional reconstructions. In addition, the amount of glenoid bone loss can be verified arthroscopically by measuring the distance from the glenoid rim to the bare spot, thereby assisting the surgeon in identifying an inverted pear glenoid, and confirming substantial bone loss and the likely failure of an isolated soft tissue repair. The threshold beyond which a soft tissue repair is likely to fail is difficult to define, and significantly increased glenohumeral instability has been suggested with defects anywhere between 21% and 28.8% of the glenoid (although caution should be exercised when comparing measurement methods).

Even when the bony fragment is present, replacing it is not always sufficient to restore the bony glenoid articular arc, especially when recurrent episodes of instability have further eroded the remaining glenoid edge. There are also issues regarding healing in this potentially necrotic bone. In these cases a bony reconstruction should be considered.

Humeral bone loss

The location and size of the Hill-Sachs lesion determines the degree to which the articular arc is reduced and when the lesion will engage on the glenoid. Dynamic arthroscopy with the shoulder in abduction and external rotation will demonstrate whether the lesion will engage during a functional or athletic overhead range of movement. To reduce the chances of recurrence, the articular arc must be increased to prevent early engagement of the lesion on the glenoid rim when the arm is externally rotated; this can be achieved with the use of a bone block procedure. An alternative to this would be the “remplissage” procedure as described by Purchase and colleagues (suturing of the infraspinatus and posterior capsule into the defect).

By enlarging the glenoid articular arc with a bone graft, the joint surface contact areas are increased and therefore the joint surface contact pressures are reduced during external rotation. The remplissage procedure does not alter the joint contact surface areas or increase the articular arc, and therefore has no effect on reducing the joint contact pressures, which may then have an effect on the development of future arthrosis. Advancing the infraspinatus and capsule into the humeral bony defect can also significantly decrease the amount of external rotation the patient may be able to achieve postoperatively.

Combinations of glenoid and humeral bone loss

These 2 lesions usually occur in tandem with varying degrees of severity. Preoperative radiographs ( Fig. 3 ) and CT scans usually identify these lesions, but an arthroscopic dynamic evaluation of stability is necessary to determine the likely clinical effects of this combination ( Fig. 4 ). The presence of an engaging Hill-Sachs lesion coexisting with a glenoid bone defect markedly reduces the defect size threshold at which recurrence will occur if the patient had only one soft tissue or bony defect in isolation. Latarjet procedure is found to be appropriate to address the abnormal anatomy.

Revision Surgery for Instability

If the initial stabilizing procedure fails because of any of the reasons mentioned earlier, then a Latarjet procedure is ideally suited to restore stability. However, a second group of patients were observed who had seemingly successful Bankart repairs but went on to develop postoperative recurrent instability after 5 to 7 years. In this particular group, the soft tissue stabilization was adequate to return the patient to a sedentary lifestyle but it had not restored satisfactory stability for more active and sporting pastimes. This finding can in part explain the excellent results seen in series with a short follow-up. In these cases, although the initial operation was considered successful, the pathologic lesion was never truly corrected and the glenoid subsequently became increasingly eroded. These patients can be effectively managed with a Latarjet as well.

Patient Activity

Many patients now demand a quicker return to sports or their occupation, or they have a high risk of recurrence. This is particularly true for patients involved in collision sports (eg, rugby), overhead sports (eg, climbing), throwing sports, and high-demand physical overhead occupations (eg, carpentry). The ability to recreate a stable shoulder with a reduced rehabilitation time to return to full activity is another advantage of the arthroscopic Latarjet technique.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree