Arthroscopic Débridement and Glenoidplasty for Shoulder Degenerative Joint Disease

Christian J.H. Veillette

Scott P. Steinmann

DEFINITION

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative disorder of synovial joints characterized by focal defects in articular cartilage with reactive involvement in subchondral and marginal bone, synovium, and para-articular structures.1,9

Patients with degenerative joint disease (DJD) of the shoulder often have coexisting pathology, including bursitis, synovitis, loose bodies, labral tears, osteophytes, and articular cartilage defects.2,3,8

Arthroscopic débridement may be a reasonable treatment option in these patients after conservative methods have been unsuccessful and when joint replacement is not desired.

Historically, patients who have early OA in whom concentric glenohumeral articulation remains with a visible joint space on the axillary radiograph are candidates for arthroscopic débridement.13

Patients with severe glenohumeral arthritis for whom shoulder arthroplasty is not ideal, such as young or middle-aged patients and older patients who subject their shoulders to high loads or impact, remain an unresolved clinical problem and are potential candidates for arthroscopic techniques.

There are five basic options for arthroscopic treatment in a patient with DJD of the shoulder:

Glenohumeral joint débridement (includes removal of loose bodies and osteophyte resection)

Capsular release

Subacromial decompression

Biceps tenodesis7

Glenoidplasty

Choosing which of these five options to perform on a shoulder with DJD depends on the degree of arthritis and the skill, philosophy, and experience of the surgeon.

Recently, Millett et al7 have advocated to also perform an axillary nerve decompression if patients complain of posterior or lateral shoulder pain on preoperative examination, if preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows encroachment on the nerve or if the inferior osteophyte appeared to compress the axillary nerve during arthroscopic evaluation.

The goal of arthroscopic débridement is to provide a period of symptomatic relief rather than reverse or halt the progression of OA.

ANATOMY

The normal head-shaft angle is about 130 degrees, with 30 degrees of retroversion.

The articular surface area of the humeral head is larger than that of the glenoid, allowing for large normal range of motion.

Glenoid version, the angle formed between the center of the glenoid and the scapular body, averages 3 degrees and is critical for stability.

The glenoid fossa provides a shallow socket in which the humeral head articulates. It is composed of the bony glenoid and the glenoid labrum.

The labrum is a fibrocartilaginous structure surrounding the periphery of the glenoid. The labrum provides a 50% increase in the depth of the concavity and greatly increases the stability of the glenohumeral joint.

The glenoid had an average depth of 9 mm in the superoinferior direction and 5 mm in the anteroposterior direction with an intact labrum.4,6

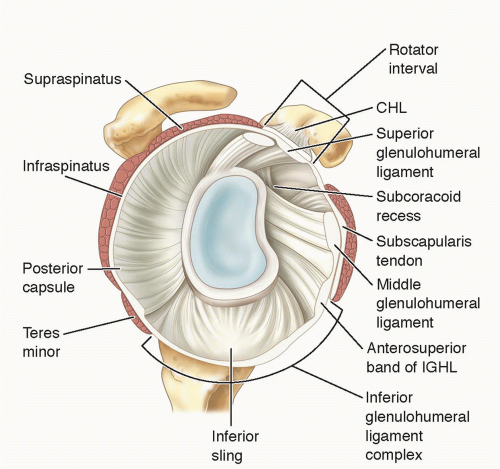

Capsuloligamentous structures provide the primary stabilization for the shoulder joint (FIG 1).

Within this capsule are three distinct thickenings that constitute the superior glenohumeral ligament, middle glenohumeral ligament, and inferior glenohumeral ligament.

PATHOGENESIS

OA may be classified as primary, when there is no obvious underlying cause, or secondary, when it is preceded by a predisposing disorder.

Pathology in patients with glenohumeral OA includes a degenerative labrum, loose bodies, osteophytes, and articular cartilage defects in addition to synovitis and soft tissue contractures.

FIG 1 • Glenoid anatomy. The glenoid has an average depth of 9 mm in the superoinferior direction and 5 mm in the anteroposterior direction with an intact labrum.

The disease process in OA of the shoulder parallels that of other joints. Degenerative alterations primarily begin in the articular cartilage as a result of either excessive loading of a healthy joint or relatively normal loading of a previously disturbed joint.11

Progressive asymmetric narrowing of the joint space and fibrillation of the articular cartilage occur with increased cartilage degradation and decreased proteoglycan and collagen synthesis.

Subchondral sclerosis develops at areas of increased pressure as stresses exceed the yield strength of the bone and the subchondral bone responds with vascular invasion and increased cellularity.

Cystic degeneration occurs owing to either osseous necrosis secondary to chronic impaction or the intrusion of synovial fluid.

Osteophyte formation occurs at the articular margin in nonpressure areas by vascularization of subchondral marrow, osseous metaplasia of synovial connective tissue, and ossifying cartilaginous protrusions.

Fragmentation of these osteophytes or of the articular cartilage itself results in intra-articular loose bodies. In late stages, complete loss of articular cartilage occurs, with subsequent bony erosion.

Posterior glenoid erosion is predominant, leading to increased retroversion of the glenoid and predisposing to subluxation and reduction of the humeral head, causing symptoms of instability.

NATURAL HISTORY

Information on the natural history of OA in individuals and its reparative processes is limited.

Progression of OA is considered generally to be slow (10 to 20 years), with rates varying among joint sites.9

No specific longitudinal studies exist on the progression of shoulder OA.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Typical history for patients with OA is progressive pain with activity over time.

In early stages, pain is related to strenuous or exertional activities, but over time, it progresses to activities of daily living. In later stages, pain occurs at rest and at night.

Pain may be mistaken for impingement syndrome early in the disease process or rotator cuff disease when symptoms occur in the presence of good motion.

Progression of the disease often leads to secondary capsular and muscular contractures with loss of active and passive motion.

Mechanical symptoms such as catching and grinding are often reported with use of the shoulder.

The pain of shoulder OA can be divided into three types:

Pain at extremes of motion: due to osteophytes and stretching of the inflamed capsule and synovium

Pain at rest: due to synovitis (pain at night is not the same as pain at rest and may be due to awkward positions or increased pressure)

Pain in the mid-arc of motion: usually associated with crepitus and represents articular surface damage

Physical examination should include the following:

Range of motion: Loss of both active and passive motion consistent with soft tissue contractures. In patients with preserved passive motion but loss of active motion, rotatory cuff pathology should be ruled out.

Compression-rotation test: Pain during mid-arc of motion is a potentially poor prognostic indication.

Neer test and Hawkins test: Often, patients with OA have positive impingement signs related to articular lesions in the glenohumeral joint or to the synovitis in the joint and subacromial pathology.

Supraspinatus evaluation: Weakness may reflect associated supraspinatus tear. Patients with OA may have weakness related to pain inhibition on resistance.

Infraspinatus and teres minor evaluation: Weakness may reflect associated posterior rotator cuff tear. Patients with OA may have weakness related to pain inhibition on resistance.

Subscapularis evaluation: Weakness may reflect associated subscapularis tear. Patients with OA may have weakness related to pain inhibition on resistance.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A standard shoulder series consisting of a true anteroposterior view in the scapular plane, a scapular lateral view, and an axillary view should be obtained on all patients before surgical intervention (FIG 2A,B).

Classic findings of glenohumeral OA are joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, subchondral cysts, and osteophyte formation.

Posterior wear of the glenoid is often noted on the axillary view in later stages of the disease.

MRI is more sensitive for the diagnosis of early-stage OA than plain radiographs and can identify concurrent soft tissue pathology.

Up to 45% of patients with grade IV chondral lesions can have no radiographic (MRI or plain radiograph) evidence of OA on preoperative imaging.2,12

Computed tomography scanning provides improved visualization of the bony glenoid, osteophytes, and loose bodies (FIG 2C).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree