Arthrodesis and Other Salvage Procedures: When Arthroplasty Is Not Indicated

Robin R. Richards

R. R. Richards: Surgeon-in-Chief and Professor of Surgery, Sunnybrook and Women’s College Health Sciences Center, and the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

INTRODUCTION

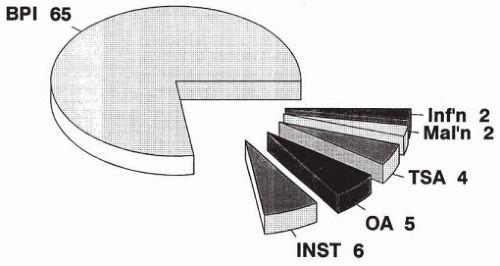

The advent of total shoulder arthroplasty and the refinement of other reconstructive procedures have narrowed the indications for shoulder arthrodesis.42 Nevertheless, arthrodesis of the glenohumeral joint continues to provide a valuable method of shoulder reconstruction for specific indications.14,23,63 During the last decade, I have performed shoulder arthrodesis for the indications listed in Figure 29-1. Although the procedure is infrequently performed, it is a reliable method of providing patients with a stable, strong shoulder. The conventional methods of performing shoulder arthrodesis must be modified for complex and revision problems. These modifications are discussed in this chapter.

Albert1 first attempted shoulder arthrodesis in 1881. Since then, a voluminous literature has evolved outlining different indications for the procedure and a variety of surgical techniques for performing shoulder arthrodesis. Controversies have developed in the literature regarding the indications for the procedure and the optimum position for shoulder arthrodesis,2,55 and debate has arisen concerning the functional results that can be achieved with the procedure.10 In this chapter, I discuss the historical perspective of shoulder arthrodesis, the anatomy and biomechanics of the procedure (including the optimum position for placement of the arm), the indications and contraindications for the procedure, the alternative procedures, and my approach to treatment. Complex and revision problems are addressed, and the complications and results of shoulder arthrodesis are discussed.

Arthrodesis is an important method of shoulder reconstruction. The procedure has stood the test of time and continues to deserve a place in the shoulder surgeon’s armamentarium. For certain specific indications, it provides the best method of restoring function to the shoulder.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Many techniques for shoulder arthrodesis have been reported. Some investigators have used extra-articular arthrodesis, others have reported on methods of intra-articular arthrodesis, and still others have used a combination of the two methods. In reviewing the literature, it is apparent that internal fixation has been used more

frequently in recent years. Historically, most investigators have recommended external immobilization, although later reports of shoulder arthrodesis without external immobilization have appeared.29,53 Extra-articular arthrodesis, intra-articular arthrodesis, the use of internal fixation, and the use of external fixators are addressed in the following sections.

frequently in recent years. Historically, most investigators have recommended external immobilization, although later reports of shoulder arthrodesis without external immobilization have appeared.29,53 Extra-articular arthrodesis, intra-articular arthrodesis, the use of internal fixation, and the use of external fixators are addressed in the following sections.

Extra-articular Arthrodesis

Extra-articular arthrodesis is primarily a historical procedure that was used before the antibiotic era to treat tuberculous arthritis. This treatment method was used to avoid entering the tuberculous joint and to obliterate motion at the joint without activating and spreading the infection. Watson-Jones62 described a technique using a Cubbins approach to the shoulder, decorticating the superior and inferior surfaces of the acromion. A bone flap was then cut into the greater tuberosity, and the clavicle and the acromion were osteotomized. The arm was abducted, and the acromion was positioned to lie between the two edges of the bone flap in the proximal humerus. A spica cast was applied for 4 months.

Putti46 described a technique whereby the spine of the scapula and the acromion were exposed subperiosteally. The spine of the scapula was detached, the acromion was split, and the medial and lateral portions and the upper end of the humerus were exposed. The lateral surface of the humerus was split similar to the method described by Watson-Jones,62 and the spine of the scapula was driven down into the humerus with the arm abducted. Spica cast immobilization was necessary after this procedure. Neither the Watson-Jones nor the Putti technique was truly extra-articular, because the shoulder joint was usually entered when creating the split in the proximal humerus.

Brittain7 described a true extra-articular arthrodesis. This arthrodesis used a large tibial graft that was placed between the medial humerus and the axillary border of the scapula. The graft was maintained in position by its arrow shape; the pointed end was inserted into the humerus, and the opposite, notched end was inserted into the axillary border of the scapula. The graft was stabilized by its shape and adduction of the arm, which produced a compressive force along the long axis of the graft. DePalma13 reports that the failure rate of the arthrodesis was high because of fracture of the long tibial graft.

Intra-articular Arthrodesis

Gill19 combined intra-articular and extra-articular arthrodesis. Gill used a U-shaped incision centered 2 cm below the acromion combined with a downward limb of the incision. Gill denuded the superior and inferior surface of the acromion and excised the rotator cuff. The glenoid fossa was decorticated, as was the cartilaginous surface of the humeral head. An osseous flap was elevated from the anterolateral surface of the humerus, and a wedge-shaped slice of bone with its base superiorly was removed from the humerus. The arm was then abducted and impacted onto the acromion. The position was maintained by suture of the capsule and rotator cuff to the periosteum on the superior surface of the acromion. This technique is predicated on the assumption that it is desirable to fuse the glenohumeral joint in a large amount of abduction. This can be desirable in children when internal fixation is not used, because with time the amount of abduction decreases. The technique is undesirable in adults because of the likelihood of excessive abduction being retained after arthrodesis.

Makin34 described a method of shoulder arthrodesis in children that preserved the growth potential of the proximal humeral epiphysis. Makin fused the shoulder in 80 to 90 degrees of abduction, fixing the humerus to the glenoid with Steinmann pins inserted first into the humerus in a proximal to distal direction and then driven in the reverse direction into the glenoid. Makin monitored his pediatric patients until adulthood and noticed that there was only a small loss in humeral length and no change in position of the fused shoulder. He recommended this technique stating that this amount of abduction was necessary to maintain the growth potential of the proximal humeral epiphysis. If this amount of abduction was maintained, the shoulder would be dysfunctional in adulthood.

Moseley38 reported division of the rotator cuff insertion and excision of the intra-articular portion of the biceps tendon. Moseley advocated suture of the biceps tendon into the bicipital groove after division of its origin. This is an important step in patients who have functioning biceps to avoid the unsightly cosmetic deformity identical to that seen in rupture of the long head of the biceps tendon and to avoid the small loss of elbow flexor power and greater loss of supinator strength that is associated with this pathologic condition. I perform a biceps tenodesis during shoulder arthrodesis in all patients who have a functional biceps. Mosely denuded the inferior surface of the acromion and the articular cartilage of the humeral head and glenoid fossa. This is an important step in performing shoulder

arthrodesis, because the humeral head presents such a small area to the glenoid across which fusion can occur.

arthrodesis, because the humeral head presents such a small area to the glenoid across which fusion can occur.

Beltran and colleagues5 performed shoulder arthrodesis through an anterior approach. They osteotomized the coracoid and created a tunnel that crossed the humerus and entered the glenoid cavity. They used a screw for internal fixation and a Cloward reamer to position a fibular graft from the proximal humerus into the infraglenoid area. Other techniques for shoulder arthrodesis have been described by May35 and by Davis and Cottrell.12

Internal Fixation

A variety of methods of internal fixation have been advocated for shoulder arthrodesis. It is generally agreed that internal fixation is desirable because it maintains the position of the arthrodesis and can decrease the length of time that plaster immobilization is necessary to obtain an arthrodesis. Makin advocates the use of Steinmann pins in children who are undergoing shoulder arthrodesis at an early age. Carroll8 described the use of a wire loop to maintain the position of shoulder arthrodesis. Carroll advocated the use of 22-gauge wire passed through the head of the humerus and the anterosuperior lip of the glenoid. He used this method of arthrodesis in 15 patients, and all patients achieved solid bony union between the third and fourth month after surgery. Carroll observed that it was possible to manipulate the shoulder after surgery and change the position of the arthrodesis. As time has gone by, most investigators have advocated more rigid forms of internal fixation. Few surgeons now use a wire loop as a method of internal fixation when performing shoulder arthrodesis. Mohammed36 reported on the use of a Rush rod combined with a tension band wire to obtain arthrodesis in 4 patients with paralysis caused by brachial plexus injury and in 14 patients with paralysis caused by poliomyelitis.

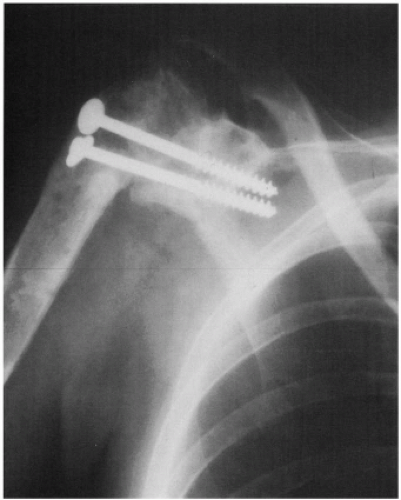

Other researchers have reported the use of screws to obtain fixation during glenohumeral arthrodesis (Fig. 29-2). May35 used a single stabilizing wood screw crossing the humerus and entering the glenoid fossa. Davis and Cottrell12 used a similar technique and added a muscle pedicle bone graft that was fixed in place with wood screws. Cofield and Briggs11 and Leffert31 also reported the use of compression screw fixation without the use of a plate. Beltran et al.5 developed a special fixation device using a screw bolt and washer to obtain shoulder arthrodesis. Beltran and colleagues also used an acromiohumeral screw and a fibular graft as methods of internal fixation.

The Orthopedic Surgical Instruments and Implants (Association for the Study of Internal Fixation [ASIF]) group first advocated the use of plate fixation in 1970. They described this method of arthrodesis as not requiring supplementary plaster immobilization. The AO/ASIF group advocated the use of two plates for internal fixation.39 The first plate was applied along the spine of the scapula and then bent down over the humerus, maintaining a position of 70 degrees of abduction between the vertebral border of the scapula and the humerus. The object of this position was to obtain a clinical position of 50 degrees of abduction, 40 degrees of internal rotation, and 25 degrees of flexion. They anchored this plate to the scapula with a long screw placed down through the plate, through the acromion, and into the neck of the glenoid. They observed that fixation could be improved by the insertion of two long screws inserted through the plate, the humeral head, and into the glenoid. If necessary, a second plate applied posteriorly was advocated to improve the internal fixation. I have rarely found it necessary to use two plates when performing shoulder arthrodesis.

Kostiuk and Schatzker29 described the use of the ASIF technique. They did not use external immobilization postoperatively and reported good results for their patients. Riggins53 described shoulder fusion without external immobilization in 1976. The AO group and Riggins supplemented their arthrodeses with bone grafts. Riggins treated four patients with the use of a plate for internal fixation.

Two of the patients had above-elbow amputations. The arthrodesis was successful in each case.

Two of the patients had above-elbow amputations. The arthrodesis was successful in each case.

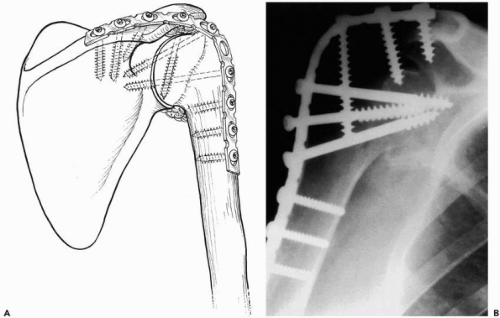

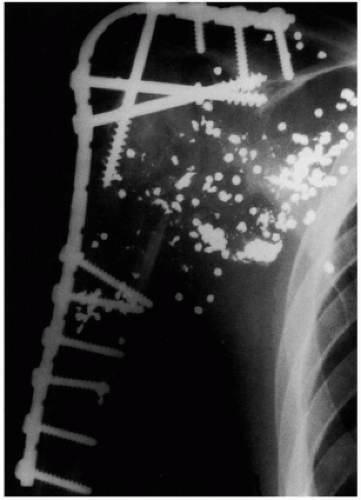

My colleagues and I have reported the results of a modified method of shoulder arthrodesis using internal fixation in 14 adult patients with brachial plexus palsy.48 We first used a single AO/ASIF dynamic compression plate for 4.5-mm screws applied over the spine of the scapula onto the shaft of the humerus. We advocate placement of two cancellous compression screws passing through the plate and proximal humerus into the glenoid to achieve compression at the glenohumeral arthrodesis site. The plate is anchored to the scapula with a long screw passing through the spine of the scapula into the area of the coracoid base. Anchorage of the plate by this method, unlike that of the AO method, which inserts the screw into the glenoid neck, provides good fixation yet leaves room for the large compression screws in the glenoid, which are thought to be more important in obtaining arthrodesis. Initially, we advocated the use of a postoperative spica cast, because adult patients with brachial plexus injuries generally have significant osteoporosis, poor muscular control, and decreased proprioception resulting from their neurologic injury. Bone grafts were not used in this series, and nonunions did not occur. More recently we have begun to use thermoplastic thoracobrachial orthoses when performing shoulder arthrodesis and no longer use a spica cast.

My colleagues and I reported a modification of the technique described in 1985.49 The current technique uses a malleable plate for internal fixation. In the modified procedure, a single 10-hole, AO pelvic reconstruction plate for 4.5-mm screws is used for internal fixation. This plate, although weaker than the dynamic compression plate for 4.5-mm screws, is much easier to contour in the operating room and much less prominent as it passes over the acromion onto the shaft of the humerus (Fig. 29-3). None of the 11 patients whose shoulders were fused by this method complained of plate prominence. Fusion was obtained in each instance without the internal fixation device failing. External cast immobilization was used for 6 weeks postoperatively. Plate prominence can also be

decreased postoperatively by notching the acromion laterally where the plate crosses this structure.

decreased postoperatively by notching the acromion laterally where the plate crosses this structure.

External Fixation

Charnley and Houston9 reported a method of compression arthrodesis of the shoulder using two Steinmann pins. The first Steinmann pin was inserted posterosuperiorly into the base of the acromion and then into the main mass of the scapula just proximal to the glenoid. The second pin is inserted posterolaterally in relation to the shaft of the humerus and perpendicular in relation to the axis of the humerus to transfix the region of the surgical neck. A compression apparatus is then applied to the two pins. After application of the compression apparatus, a plaster spica cast was applied and worn for an average of 4.8 weeks. After removal of the pins and compression clamps, a second plaster cast was applied for an average of 5.3 weeks. Other methods of external fixation have been reported.24,28,40,59

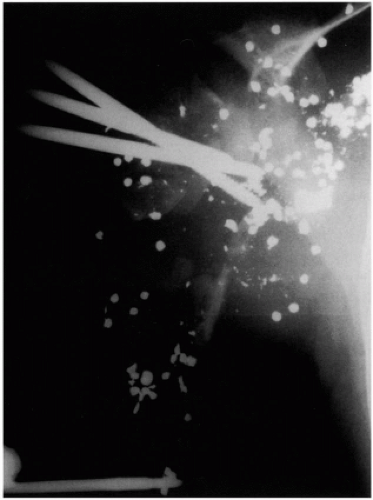

The indications for shoulder arthrodesis using external fixation are limited. I have used this method occasionally in patients with active septic arthritis of the shoulder and in patients with massive trauma resulting in bone and soft tissue loss (Fig. 29-4). I have used pins placed through the clavicle and acromion and a second set of pins inserted in a separate plane into the spine of the scapula and neck of the glenoid. Two half frames are then constructed to stabilize the shoulder. The two half frames can be cross-connected for increased stability. This technique is desirable if there is an open infected wound draining from the shoulder joint. This method allows dressing changes and care of the soft tissues without the increased dissection and soft tissue disruption necessary to place an internal fixation device. If the soft tissue envelope improves, internal fixation can be used in a delayed fashion (Fig. 29-5).

Figure 29-5 Conversion of external fixator to plate fixation to obtain arthrodesis in the same patient as in Figure 29-4. |

ANATOMY AND BIOMECHANICS OF SHOULDER ARTHRODESIS

Many positions for glenohumeral arthrodesis have been advocated in the literature. Perusal of the literature reveals that no two surgeons agree on the optimum position for

shoulder arthrodesis. There was sufficient controversy in the literature that the American Orthopaedic Association established a committee to determine, among other things, the optimum position for shoulder arthrodesis. In 1942, this committee2 concluded that the optimum position for shoulder arthrodesis was 45 to 50 degrees abduction (measured from the vertebral border of the scapula), 15 to 25 degrees of forward flexion from the plane of the scapula, and 25 to 30 degrees of internal rotation. This report caused a great deal of controversy in the literature after its publication. Part of the controversy revolved around the method of measurement of abduction. Some surgeons recommended using the angle formed by the vertebral border of scapula and the axis of the humerus to determine abduction, and others argued that the angle between the arm and the side of the body was more appropriately measured (i.e., clinical abduction).

shoulder arthrodesis. There was sufficient controversy in the literature that the American Orthopaedic Association established a committee to determine, among other things, the optimum position for shoulder arthrodesis. In 1942, this committee2 concluded that the optimum position for shoulder arthrodesis was 45 to 50 degrees abduction (measured from the vertebral border of the scapula), 15 to 25 degrees of forward flexion from the plane of the scapula, and 25 to 30 degrees of internal rotation. This report caused a great deal of controversy in the literature after its publication. Part of the controversy revolved around the method of measurement of abduction. Some surgeons recommended using the angle formed by the vertebral border of scapula and the axis of the humerus to determine abduction, and others argued that the angle between the arm and the side of the body was more appropriately measured (i.e., clinical abduction).

In 1974, Rowe55 noticed that the amount of abduction that had been recommended was excessive for adults. This position had been recommended primarily for patients who had their shoulders fused as children and in whom internal fixation was not used. In this situation, the amount of abduction at the time of surgery was commonly lost during the period required for arthrodesis to become secure and during continued growth. If the same position was used in adults, excessive scapular winging would occur, and the scapula would not comfortably rest at the side. Rowe observed that the measurement of clinical abduction was more practical and recommended this method rather than measuring abduction from the vertebral border of the scapula. Rowe recommended that the arm be placed nearer the center of gravity of the body with enough abduction to clear the axilla and sufficient flexion and internal rotation to bring the hand to the midline of the body.

Other surgeons have recommended a variety of positions for shoulder arthrodesis. All investigators agree that abduction and forward flexion are desirable. Most have recommended internal rotation. I think the optimum position for shoulder arthrodesis is one that brings the hand to the midline anteriorly so that with elbow flexion the mouth can be reached. The amount of abduction should not be excessive so that the arm can rest comfortably at the side. I recommend a position of 30 degrees of abduction (measured clinically), 30 degrees of forward flexion, and 30 degrees of internal rotation. This so-called 30-30-30 position is easily obtained in the operating room and provides patients with the ability to reach the mouth, a front pocket, and a back pocket in most instances (Fig. 29-6). The position cannot always be measured exactly at the time of surgery. I found in a series of shoulder arthrodeses that it is usually possible for the shoulder to undergo arthrodesis within 10 degrees of the described position.

INDICATIONS FOR SHOULDER ARTHRODESIS

Shoulder arthrodesis can effectively restore shoulder function to patients with certain disorders. Patient selection is important in determining whether the procedure will be beneficial. The procedure results in the effective sacrifice of all rotation through the glenohumeral joint. However, shoulder arthrodesis does provide strength and stability. When possible, shoulder arthroplasty is preferable to shoulder arthrodesis if there is a choice for the patient between the two procedures. Shoulders can be fused if an arthroplasty fails, although fusion in this situation is a technical challenge. The indications used for surgery in my series are illustrated in Figure 29-1.

Paralysis

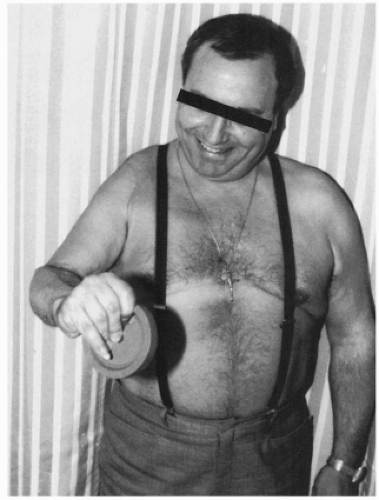

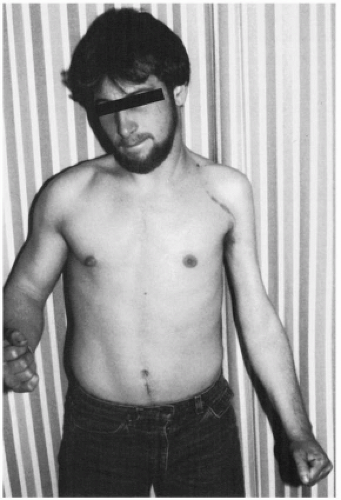

All investigators agree that a flail shoulder is an indication for shoulder arthrodesis. Patients with anterior poliomyelitis, patients with severe proximal root and irreparable upper trunk brachial plexus lesions, and some patients with isolated axillary nerve paralysis are candidates for shoulder arthrodesis.53 These patients have good function in their elbows and hands but are unable to optimize their

upper extremity function because of their inability to place their hand in space (Fig. 29-7). If such a patient has good function in the periscapular musculature, particularly the trapezius, levator scapula, and serratus anterior, glenohumeral arthrodesis stabilizes the extremity and allows effective hand function.50 The patients can then fully use their upper extremity potential and can work effectively at bench level. Many patients with flail shoulders develop inferior subluxation of the glenohumeral joint caused by periarticular paralysis. This condition is uncomfortable and, in some patients, frankly painful. Such patients often find that they must keep their affected arms in slings to avoid injury. Painful inferior subluxation of the shoulder provides another indication for stabilization of the glenohumeral joint.

upper extremity function because of their inability to place their hand in space (Fig. 29-7). If such a patient has good function in the periscapular musculature, particularly the trapezius, levator scapula, and serratus anterior, glenohumeral arthrodesis stabilizes the extremity and allows effective hand function.50 The patients can then fully use their upper extremity potential and can work effectively at bench level. Many patients with flail shoulders develop inferior subluxation of the glenohumeral joint caused by periarticular paralysis. This condition is uncomfortable and, in some patients, frankly painful. Such patients often find that they must keep their affected arms in slings to avoid injury. Painful inferior subluxation of the shoulder provides another indication for stabilization of the glenohumeral joint.

Patients who have the combination of a flail shoulder and flail elbow need shoulder and elbow reconstruction. In this situation, glenohumeral arthrodesis combined with elbow flexorplasty improves the result of the elbow flexorplasty. Without shoulder stabilization, elbow flexion tends to drive the humerus posteriorly, resulting in shoulder extension rather than elbow flexion. Arthrodesis of the shoulder in some flexion and abduction helps to reduce the effect of gravity and optimize the result that can be achieved with the elbow flexorplasty. Patients with flail shoulders often have a tendency to internally rotate the upper extremity to the chest when some function remains in the powerful internal rotators of the shoulder (e.g., pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi) and no function remains in the external rotators. Shoulder stabilization in the form of arthrodesis or a L’Episcopo tendon transfer reduces this undesirable tendency.

There is great variability in the disability caused by axillary nerve paralysis, and I have seen many patients who have virtually full motion after paralysis of the axillary nerve, providing the rotator cuff musculature is undisturbed (endurance is never normal). Patients with isolated paralysis of the axillary nerve can be treated by muscle or tendon transfer or glenohumeral arthrodesis. Numerous reports exist in the literature on the value of muscle and muscle tendon transfer to restore shoulder function after paralysis of the axillary nerve.8,20 It is generally agreed that multiple transfers are necessary to restore deltoid function and that significant problems can occur with gliding of transfers over the acromion. It is often necessary to harvest autogenous tissue such as fascia lata to prolong the transfers, and the process of rehabilitation is challenging after such procedures. In my experience, such transfers are indicated primarily for pediatric patients and adult patients who have only partial paralysis of the axillary nerve.20 However, pediatric patients do well with shoulder arthrodesis, and some investigators believe they are better able to adapt to the procedure.33 If total paralysis of the axillary nerve exists and significant limitation of shoulder function ensues, I recommend glenohumeral arthrodesis, recognizing that the alternative of muscle transfers may be available in carefully selected patients. Ruhmann et al.57 reported on the differential function in patients with brachial plexus palsy after reconstruction with either tendon transfer or arthrodesis. I have found glenohumeral arthrodesis to be useful in such patients, provided their symptoms justify the procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree