Approach to the Patient with Shoulder Pain: Introduction

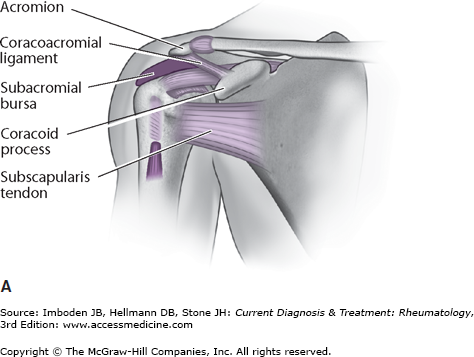

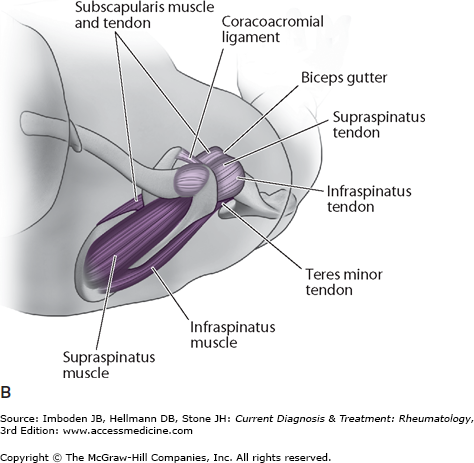

The shoulder complex consists of four joints—the glenohumeral, acromioclavicular (AC), sternoclavicular (SC), and scapulothoracic joints—with encapsulating ligaments and muscles (Figure 8–1). It is the most mobile joint of the body, with the primary role of positioning the hand in space to function. A detailed history and physical examination with appropriate imaging can help narrow the extensive differential diagnosis and guide treatment. Most conditions can be treated initially with medication and physical therapy. Resistant shoulder pain should be referred for orthopedic consultation.

History

Much like pain elsewhere, shoulder pain can be initially categorized by onset of symptoms, character of pain, and what activities relieve and aggravate the pain.

The onset of pain may follow a recent injury (≤4 weeks) or remote injury (>4 weeks). Recent injury usually has an acute onset of pain, whereas a remote injury may be episodic or insidious. Because the shoulder is involved in many repetitive functions, pain can result from overuse.

Character, location, timing, and radiation of pain can also be helpful. Sharp or stabbing pain usually suggests a structural cause. Dull and aching pain, especially related to early mornings and weather changes, suggests arthritis. Burning and radiating pain suggests a neurologic cause. Lateral upper arm pain is typical of rotator cuff pain. Pain radiating below the elbow or to the medial border of the scapula suggests a cervical spine or neurologic source of the pain. Pain at night is also typical of rotator cuff disease, but it can be noted in metastatic bone disease. Pain with overhead activity is a very common symptom and can be generally categorized as “impingement” pain. It is most commonly caused by rotator cuff dysfunction or disease. Constitutional symptoms, such as fever and weight loss, should alert the clinician that the cause of pain is infectious, metabolic, or neoplastic.

Other symptoms associated with shoulder pain include stiffness, weakness, and instability. A helpful way to frame the magnitude of shoulder pain is to identify the activities that are limited by the pain, such as overhead use, lifting, dressing, combing or shampooing hair, washing, and hygiene. Recreational and occupational limitations should also be sought.

Physical Examination

For an accurate examination, the shoulder needs to be visible; for female patients, privacy can be respected by using special examination gowns or by having the patient wear a sports bra, swimsuit top, or strapless blouse.

Both shoulders should be examined not only from the front but also from the back and side. Particular attention should be paid to shoulder symmetry to allow the clinician to appreciate subtle muscle atrophy. Atrophy suggests neurologic injury or chronicity of the underlying problem.

Palpating the shoulder and assessing its range of motion are the next steps in the physical examination.

Palpation begins at the SC joint and moves lateral over the clavicle to the AC joint and should be sensitive to deformity, pain, and crepitance. The presence of SC and AC joint pain or deformity can suggest injury or arthritis or both. A painful acromion may indicate an os acromiale. Next, the greater and lesser tuberosities (insertions of the supraspinatus and subscapularis, respectively) should be palpated; if pain is present, a rotator cuff abnormality should be suspected. Between the tubercles, the intertubercular groove (the course of the long head of the biceps) can be palpated. Pain at this location suggests biceps tendinitis, which can occur on its own or with rotator cuff abnormality and superior labral tears.

Because of the shoulder’s mobility, its ROM should be checked in several planes, in overhead elevation, and in internal and external rotation. In addition, ROM should be assessed actively and passively. Overhead motion should be observed from the front and back of the patient. From the back, asymmetry of excursion of the scapulae should be assessed. Winging can be observed with serratus anterior, trapezius, and infraspinatus weakness. More subtle medial border elevation is commonly seen with the painful shoulder from weak or misfiring scapular stabilizers, which contribute to the closing of the coracoacromial arch and shoulder impingement.

Internal rotation can be measured by having patients place their thumbs midline on their spines as high as they can; the level of the vertebrae touched should be recorded (Plates 12 and 13). In addition, internal and external rotation can be measured with the arm abducted 90 degrees and the elbow flexed 90 degrees.

ROM of the affected shoulder should be compared with that of the opposite side. Active ROM that is more painful and restricted than passive ROM suggests a rotator cuff component to the pain. Painful restricted passive ROM is seen in adhesive capsulitis, or “frozen shoulder.” The painful arc of motion should also be noted.

Finally, ROM of the cervical spine should also be examined, including flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation, because restricted or painful neck motion can refer pain to the shoulder.

Neurologic Examination

Muscle testing should be performed next, with special attention to assessment of rotator cuff strength. Abduction against resistance tests the supraspinatus. External rotation versus resistance tests the posterior rotator cuff muscles, infraspinatus, and teres minor. The “belly-press” test and “lift-off” tests assess the anterior rotator cuff muscle, the subscapularis (Plates 14 and 15).

Special Tests

In addition to the basic examination of the shoulder, numerous abnormality-specific tests or maneuvers can be used to help determine the cause of shoulder pain or dysfunction. Examination of adjacent anatomy (arm, elbow, forearm, hand, and cervical spine) should be performed before these tests. However, many of these tests can elicit pain and apprehension and should therefore be performed after less painful aspects of the examination; results of the affected shoulder should be compared with those of the normal side. Special tests, including the sulcus sign test, load and shift test, apprehension and relocation test, the Neer test, the Hawkins test, the Yergason test, the Speed test, and the O’Brien test, can be used to assess for abnormalities ranging from instability and rotator cuff impingement, to labral and biceps tendon disease, to disorders of the AC joint.

The shoulder joint is inherently lax, affording it a great degree of mobility. Abnormal laxity represents a spectrum of disease, ranging from painful subluxation to traumatic dislocation. Because there is a wide range of normal laxity, a determination of abnormal laxity should be made only with consideration of the individual history, baseline examination, or contralateral “normal” examination. Conditions resulting in generalized laxity of several joints should also be considered. The following are specific tests to evaluate and characterize shoulder instability.

The goal of this test is to evaluate for inferior shoulder laxity. With the patient seated, the degree of translation between the lateral border of the acromion and the humeral head is noted as downward force is applied to the distal arm in neutral rotation (Plate 16). A “sulcus,” or depression in the skin between the acromion and humeral head, is seen. Some practitioners suggest this result should be graded (grade 0, no translation; grade I (≤1 cm), mild translation; grade II (1–2 cm), moderate translation; grade III (>2 cm), severe translation), whereas others suggest the result should simply be reported as positive or negative. A positive or high-grade sulcus sign in both shoulders may suggest multidirectional instability, whereas a unilateral sulcus sign may suggest inferior instability, particularly if associated with pain or symptoms of instability.

The load and shift test measures humeral translation on the glenoid in the anterior and posterior directions. With the patient seated, the examiner places one hand over the top of the shoulder from the posterior position. The other hand grasps the upper arm, gaining control of the humeral head and controlling rotation (neutral). The first part of this maneuver involves “loading” the joint by applying axial pressure through the arm, centering the humeral head in the glenoid. From this position, anterior or posterior force can be applied (Plates 17 and 18). The examiner should then note and grade the degree of translation or subluxation that is felt as the humeral head slides over the glenoid surface. The modified Hawkins classifications assigns three translation grades: I, the humeral head does not move over the glenoid rim; II, the humeral head moves over the rim but returns to a central position; and III, the humeral head moves beyond the rim and requires a reduction maneuver to return to anatomic position. The load and shift test is highly specific: a negative result indicates a high likelihood that anterior or posterior instability is not present.

The apprehension test evaluates anterior instability by attempting to reproduce symptoms with the arm in a position of abduction and external rotation. The test can be performed with the patient seated or supine. The examiner positions the patient’s arm in increasing amounts of abduction and external rotation while determining whether the patient becomes apprehensive about impending subluxation or dislocation (Plates 19 and 20). A positive test, indicated by the patient’s feeling of apprehension, not simply pain, is suggestive of anterior instability. The positive predictive value of this test approaches 98%.

The relocation test is performed in the supine position after the patient’s arm is in a position that produces apprehension. The examiner then places one hand anteriorly on the shoulder and applies a posterior force, reducing any humeral head translation. The test is considered positive if this maneuver relieves the sense of apprehension. This test is also very specific and has a 100% positive predictive value for anterior instability.

Patients with rotator cuff pain often note positional pain at night and with overhead activity; however, the pain is usually poorly localized around the anterior or lateral aspect of the shoulder. The Neer and Hawkins tests are frequently used to reproduce this pain and assess for “impingement,” which is believed to be a major cause of rotator cuff tendinitis.

The Neer test is performed by first stabilizing the scapula and then passively raising the patient’s arm in forward elevation (Plate 21). The patient’s report of pain constitutes a positive result and usually occurs at approximately 80 degrees to 120 degrees of elevation (the point at which the anterior rotator cuff impinges on the undersurface of the acromion). This test is nonspecific for rotator cuff abnormality and may yield a positive result for other conditions, such as adhesive capsulitis, subacromial bursitis, instability, and arthritis.

The Hawkins test is a variation of the Neer test and involves the examiner internally rotating the patient’s 90-degree forward-elevated arm with the elbow in flexion (Plate 22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree