Approach to the Patient with Neck Pain: Introduction

Neck pain is a common musculoskeletal symptom and accounts for a sizeable portion of the 9.3 million physician visits annually in the United States for soft tissue disorders. Of those individuals with neck pain, 81% were between the ages of 18 and 64 years as reported by the United States Bone and Joint Decade in 2008. Mechanical disorders cause 90% of neck pain episodes. Mechanical neck pain may be defined as pain secondary to overuse of a normal anatomic structure or pain secondary to trauma or deformity of an anatomic structure (Figure 9–1). Mechanical disorders are characterized by exacerbation and alleviation of pain in direct correlation with particular physical activities. Neck pain due to mechanical disorders decreases within 2–4 weeks in over 50% of patients; symptoms usually resolve within 2–3 months.

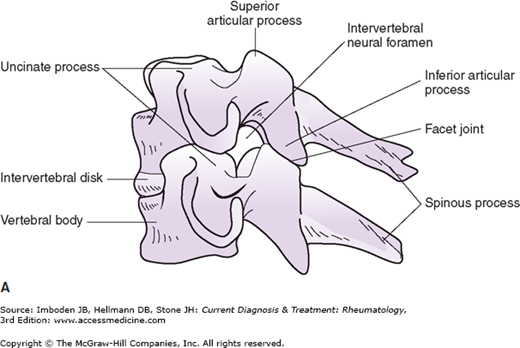

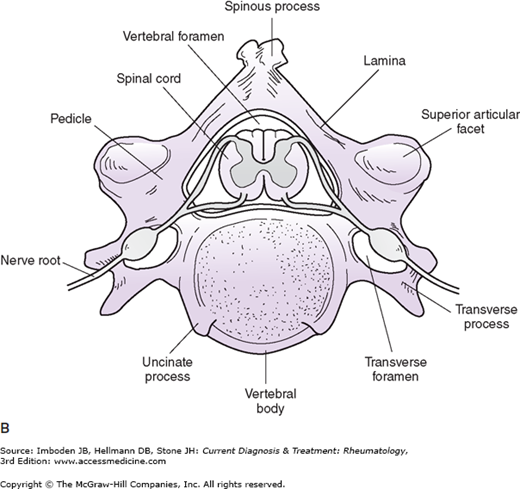

Figure 9–1.

Schematic representation of a lateral view of the mid-cervical spine (A) and the superior aspect of C5 (B). The inferior articular processes from synovial-lined facet joints (also called apophyseal joints) with the superior articular processes of the vertebra below. The uncinate processes or posterolateral lips located on the superior aspect of the vertebral bodies interact with the inferolateral aspects of the vertebral body above, forming the small, non-synovial-lined uncovertebral joints (also referred to as the joints of Luschka). The spinal cord lies within the vertebral foramen formed by the vertebral body anteriorly, the pedicles laterally, and the laminae posteriorly. The cervical nerve roots course along “gutters” formed by the pedicles and exit through an intervertebral foramen. The vertebral artery passes through the transverse foramen. (Reproduced, with permission, from Polley HF, Hunder GS. Rheumatologic Interviewing and Physical Examination of the Joints, 2nd ed. WB Saunders; 1978.)

Initial Evaluation

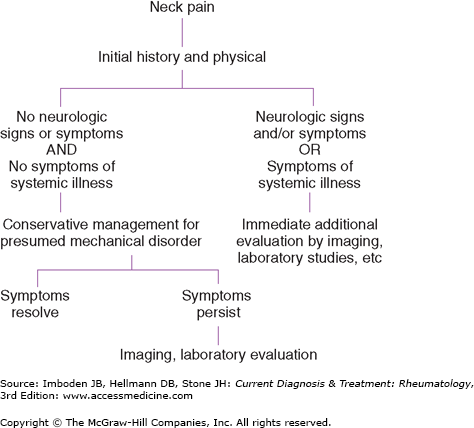

The goal of the initial evaluation is to differentiate patients with probable mechanical disorders from those with neck pain that requires more thorough immediate evaluation (Figure 9–2). A history should be taken and an examination should be performed in all patients with new-onset neck pain. The neurologic examination should determine whether there are any signs of cervical nerve root or cervical cord involvement (ie, spastic weakness, hyperreflexia, clonus, and positive Babinski signs).

Diagnostic radiographic or laboratory tests are not necessary during the initial evaluation of patients with probable mechanical neck pain. These tests, however, are indicated for patients whose history and physical findings suggest persistent compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots or raise the possibility of neck pain as a component of an underlying systemic disease.

The history should establish the character, onset, location, radiation, aggravating and alleviating factors, intensity, and chronologic development of neck pain. Mechanical disorders cause pain that increases with activity. The end of the day is associated with more severe distress, and recumbency and rest are associated with improvement. Tingling pain that radiates down an arm is suggestive of nerve impingement. Aching pain of slow onset that localizes to the base of the cervical spine suggests muscle or joint involvement. The history should determine whether the neck pain has unusual qualities that suggest a focal destructive process (due to tumor or infection) or pain referred from the heart or other viscera, whether there is an underlying systemic disease that could predispose to a serious neck problem (Table 9–1).

|

The duration of mechanical neck pain is typically a few days to weeks. Disk herniations may require 8–12 weeks to resolve. Medical conditions tend to cause persistent chronic pain.

Abnormalities of the cervical spine may be observed while the spine is in motion or static. Observation of the spine from 360 degrees identifies any misalignments of the neck or shoulders. Pain in the neck may cause deviation that can be toward or away from the painful side.

Palpation can detect painful structures as well as increased paraspinous muscle tension. Posterior elements of the cervical spine are more easily identified than those located anteriorly. In general, midline tenderness is related to an intrinsic spinal disorder, while sensitivity to pressure in structures off the midline suggests soft tissue pathology.

Active range of motion in all planes is helpful in documenting the extent but not the cause of cervical spine problems. Active and passive movement of the shoulders can help discriminate abnormalities of the appendicular skeleton from those of the cervical spine.

Neurologic evaluation, including reflex, sensory, and motor function both in the upper and lower extremities is essential to determine the extent of compromise of the central and peripheral nervous systems. The presence of long-tract signs is indicative of more severe spinal cord compression.

The Spurling maneuver is performed by extending and rotating the head to one side and then the other. A positive result is the reproduction of radicular pain. This test is useful in confirming the presence of a cervical radiculopathy.

The Adson test for thoracic outlet obstruction is performed by palpating the pulse at the wrist while abducting, extending, and externally rotating the arm. The patient takes a deep breath and rotates the head to the affected side. If there is compression of the subclavian artery, a marked diminution of the radial pulse is observed and is a positive test.

Laboratory tests are not necessary for the diagnosis of mechanical neck pain. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein tests are useful in the minority of patients with a systemic disorder causing neck pain.

Radiographic studies are needed for the small minority of patients who do not respond to a 6–8 week course of medical therapy, who demonstrate severe neurologic compromise, or who have signs or symptoms of a systemic illness.

Plain radiographs are easily obtained but offer few specific findings that identify the cause of neck pain. Many anatomic abnormalities are asymptomatic.

MRI is a useful technique for individuals with clinical symptoms and signs of nerve compression who do not respond to medical therapy. MRI is a sensitive means of identifying disk herniations, narrowing of the spinal canal, and increased inflammation in osseous and soft tissue structures. CT is a better technique at delineating bony structures. A disadvantage of CT is the exposure to ionizing radiation needed to obtain images of the spine.