Approach to the Patient with Hand, Wrist, or Elbow Pain: Introduction

The causes of upper extremity pain can be categorized as neurologic, musculoskeletal, joint-related, and vascular. A thorough history is critical to characterize the pain. Clinicians should ask specific questions about the quality of the pain (eg, aching, stabbing, throbbing, tingling, pins and needles, numbness). Radiologic and diagnostic testing can help the clinician differentiate between the sources of pain, thereby limiting the differential diagnosis. However, because pain is subjective, the objective physical, radiologic, and electrophysiologic findings sometimes correlate poorly with the intensity of the patient’s perceived pain.

Describing anatomic locations in the hand and the finger can be difficult because of their complex, three-dimensional structures. To avoid confusion and potential errors, standardized terminology should be used. While the surface of the palm can be referred to as either the palmar or the volar surface, palmar is the preferred term to avoid confusion. The back of the hand is referred to as the dorsal surface. The terms “ulnar” and “radial” are used instead of “medial” and “lateral” to describe the sides of the hand because lateral and medial sides can change based on the rotational position of the arm at the time of the examination. The side of the hand toward the small finger is referred to as the “ulnar” side, and the side toward the thumb is referred to as the “radial” side. The fingers should be referred to by name, such as the thumb, the index finger, the middle (or long) finger, the ring finger, and the small finger rather than as the first, second, third, fourth, or fifth fingers. It not infrequent that the index finger is called the first finger and the small finger is called the fourth finger. In truth, however, the thumb is the first finger and the small finger is the fifth finger.

There are 27 bones within the hand: 8 carpal bones, 5 metacarpal bones, and 14 phalangeal bones. The 8 carpal bones are arranged in two rows (a proximal and a distal) that contain 4 bones each. The scaphoid, lunate, triquetral, and pisiform form the proximal row. The distal row is formed by the trapezium (under the thumb metacarpal), the trapezoid, the capitate (which is directly under the middle finger metacarpal), and the hamate (on the ulnar side). The carpal bones are connected to each other by strong ligamentous connections. There are 5 metacarpal bones, and they should be referred to by name rather than by numbers based on the fingers to which they are attached: thumb, index, long, ring, or small metacarpal bones. The phalanges are the bones in the fingers. The thumb has 2 phalanges: the distal and the proximal phalanges. The four other fingers have 3 phalanges: the distal, middle, and the proximal phalanges. To avoid confusion, the phalanges should also be referred to by name (distal, middle, or proximal) rather than by numbers, such as P1, P2, or P3.

The vascular supply of the hand comes from the brachial artery, which separates into the radial and the ulnar arteries at the proximal forearm. These two arteries course along the ulnar and radial borders of the forearm before entering the hand. The ulnar artery feeds the superficial vascular arch of the hand, supplying blood flow to the small, ring, and long fingers. The radial artery at the distal forearm gives rise to the dorsal metacarpal artery, which supplies the dorsal hand. After this, the radial artery continues into the hand and becomes the deep palmar vascular arch, which supplies most of the arterial flow to the thumb and the index finger. In most people, the superficial and the deep vascular arches have arterial connections. The crucial consequence of this is that the hand can be perfused by either the radial or the ulnar artery in most people.

The median, ulnar, and the radial nerves are the three major nerves that provide motor and sensory function to the hand. The ulnar nerve provides the sensation to the small finger and the ulnar half of the ring finger and the dorsal ulnar surface of the hand, the dorsal small finger, and the ulnar dorsal side of the ring finger. The median nerve provides the sensation to the radial palm, the palmar surface of the thumb, index, long, and the radial half of the ring fingers. The median nerve also innervates the dorsal tips of these fingers. The dorsal radial sensory nerve, as the name suggests, provides sensation to the dorsal radial side of the hand, the dorsal surface of the thumb, index, long, and the radial dorsal side of the ring finger.

The ulnar motor fibers provide most of the innervation to the intrinsic hand muscles. The thenar muscles are primarily innervated by the recurrent branch of the median nerve. The median and ulnar nerves innervate the extrinsic long flexor muscles outside the hand in the forearm to provide finger and wrist flexion. The radial nerve innervates the extrinsic extensor muscles that extend the thumb, the fingers, and the wrist.

When evaluating the patient with hand pain, the history is critical to the diagnosis. The examiner should determine the patient’s age, handedness, and vocation. The pain should be characterized with such details as the initial onset, the duration, its specific location, if the pain radiates, and if the pain is changing and if it is, whether it is improving or worsening. The patient should be asked if there are any motor functional changes noted in the hand or the finger when the pain occurs, such as finger trigger or locking. The examiner should inquire about any aggravating and relieving factors, including specific activities at work or at home and if there is any diurnal or nocturnal variation. If there is a history of recent trauma, a precise description of the mechanism of any injuries to the area should be noted. A fracture or ligamentous injury at a joint can cause pain. A history of remote trauma is also important because it might indicate that the pain is due to degenerative changes from an untreated fracture or soft tissue injuries. Treatments including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), splinting, hand therapy, prior injections or surgeries should be noted. The patient’s medical and surgical histories including prior fractures, history of autoimmune disorders, and infections can also lead to a diagnosis.

The patient should also be asked for other symptoms that are associated with nerve compression, tendinopathies, vascular abnormalities, and arthritis. Unremitting aching and radiating pain with paresthesias that occurs at night and improves with motion or shaking the hand is likely neurogenic. Focal tenderness and swelling with repetitive activity, relieved with rest, is more likely tendinopathy. Joint pain from osteoarthritis or osteochondral injuries is often deep aching pain associated with loss of joint motion, instability, and swelling. Vascular pain is often unremitting with severe throbbing pain that is worsened with cold temperatures that can then lead to ischemic ulcerations and wound healing issues. Other causes of pain include trauma and infection. Complete physical and neurologic examinations of both upper extremities are therefore important.

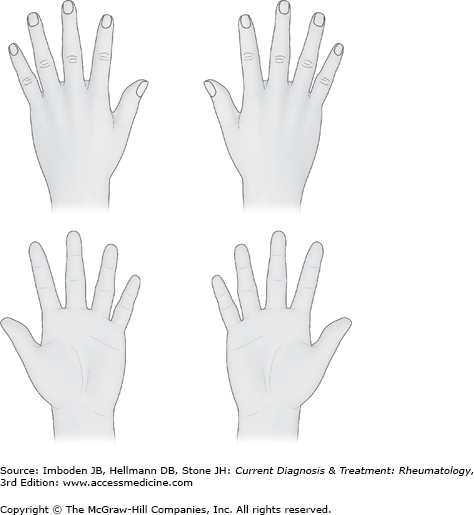

Much information can be gathered just by observing the patient’s hands while taking the history. Observe both of the hands for symmetry and posture. It is helpful to have a diagram of the hand present, so that the examiner can easily mark on the diagram the fingers that have pain or are affected (Figure 6–1). Look for calluses, scarring (traumatic or surgical), and swelling. With the hand is at rest, the fingers should be held in a normal cascade (Plate 1). This means that the small finger is flexed slightly more than the ring finger, the ring finger slightly more flexed than the long finger, and the long finger slightly flexed more than the index finger. Should the hand not have this posture, there may be a tendon rupture, laceration (Plate 2), inflammation of the tendons such as in trigger finger (see Plate 9), or fascial cords (Dupuytren contractures) that alter this repose cascade. Tenderness to palpation and stability should be assessed in each joint. Although it is tempting to touch the part of the hand that is in pain first, it is sometimes more helpful to examine the entire hand first as a unit.

The physical examination begins at the neck, assessing for pain, crepitus, and decreased range of motion. Spurling test can reproduce cervical radiculopathy pain by hyperextending the neck while turning the chin toward the affected side in order to compress the neural foramina around exiting nerve root. Reflexes at the biceps, triceps, and brachioradialis should be measured with the simple goal of determining whether the patient is hyperreflexic or hyporeflexic. The Hoffmann sign, the so-called Babinski test of the upper extremity, involves flicking the distal phalanx of the middle finger and monitoring for reflexive flexion of the thumb interphalangeal joint. Any hyperreflexia, especially when combined with an unsteady gate or difficulty with fine motor activities, should raise concern for neurologic compression and may require further evaluation by a neurologist or a spine surgeon.

The shoulder should be taken through a range of motion and all bony prominences should be palpated. Pain with passive internal rotation of the shoulder due to bony impingement can be mistaken for distal arm pain. Pain in the “shoulder patch” distribution over the deltoid can indicate rotator cuff pathology. Sensation over the shoulder, upper arm, and forearm should be tested and compared to the contralateral side to evaluate for cervical based dermatomal paresthesias. Muscle strength in the biceps (musculocutaneous nerve) and triceps (radial nerve) should be evaluated, along with the strength of forearm pronation and supination. The range of motion at the elbow as well as stability should be tested.

The sensory examination should assess the radial, ulnar, and median nerve distributions in the hand with comparisons made for both hands. Two-point discrimination testing and Semmes-Weinstein monofilament testing are sensitive early indicators of nerve dysfunction. A positive Tinel sign test over the common compression sites of the median, ulnar, and radial nerves can indicate nerve irritation due to an injury or compression.

The motor examination should assess strength. The most commonly used method is based on a numerical gradation from zero (0) to five (5) (Table 6–1). The motor and sensory function of the major nerves to the hand (radial, median, and ulnar nerves) should be assessed. Thumb opposition to the small finger indicates a functional recurrent branch of the median nerve. Ability to flex the index finger interphalangeal joint and thumb interphalangeal joint indicates that the anterior interosseous nerve branch of the median nerve is intact. The ability to adduct the fingers indicates that the ulnar motor nerve is functional. The ability to extend the fingers, the thumb, and the wrist indicates that the radial motor nerve is functional. Weakness, lack of function, or sensory changes should prompt the clinician to order a nerve conduction velocity/electromyography (NCV/EMG) study.

| Numerical Gradation | Clinical Finding |

|---|---|

| 0 | No muscle movement |

| 1 | Flicker |

| 2 | Muscle moves the joint when gravity is eliminated |

| 3 | Muscle cannot hold the joint against resistance but moves the joint fully against gravity |

| 4 | Muscle holds the joint against a combination of gravity and moderate resistance |

| 5 | Full strength |

The upper extremity vascular examination begins with a thorough inspection of the skin for discoloration, scars, rashes, hair pattern, and ulceration. Touching the hand gives the examiner a qualitative assessment of the hand vascularity based on the temperature, moisture, and quality of the skin. The fingertips should be warm and well-perfused with capillary refill less than 2 seconds. Also noted should be any temperature differences between digits; the presence of vascular masses; thrills; or the strength of brachial, radial, and ulnar arterial pulsation. As noted, the hand usually has dual blood supply through the radial and ulnar arteries, which interconnect through the superficial and deep vascular palmar arches. An Allen test should be done to ascertain perfusion to the hand via either the ulnar artery or the radial artery. The Allen test is performed by applying simultaneous pressure to the patient’s radial and ulnar arteries with the examiner’s thumb and fingers at the wrist. The patient is asked to flex the fingers three times fully before keeping the fingers fully extended. At this point, the fingers and the hand should be pale. The examiner then releases the pressure on the radial artery while maintaining pressure on the ulnar artery. If the communication between the deep arch (radial artery) and the superficial arch is patent, the fingers and the hand will reperfuse and the hand will turn pink within 2 seconds. The patient is asked again to squeeze three times and then to keep the fingers extended. This time the pressure is released from the ulnar artery while pressure is maintained on the radial artery. If the connection between the superficial arch (ulnar artery) and the deep arch is patent, the fingers and hand will reperfuse. The results of the Allen test are best stated as “the Allen test was performed, and perfusion was present through both the radial and the ulnar arteries.” If an abnormality is noted, the results are best stated as “the Allen test was performed and there is poor (or delayed) perfusion by the ulnar (or radial) artery.” When stated in this fashion, there is no confusion what a “positive” or a “negative” Allen test means.

Plain radiographs, computed tomography scans, and magnetic resonance imaging studies all have roles to play in selected musculoskeletal conditions and should be used as required to elucidate the diagnosis.

Neurologic Causes of Pain

Pain due to peripheral nerve dysfunction can present with varying symptoms, ranging from pure sensory dysfunction to pure motor paralysis or a combination of both. Most commonly, the dysfunction is due to external compression or trauma. This is in contrast to intrinsic neurologic dysfunction from metabolic causes, such as diabetes mellitus, or from demyelinating conditions, such as the Charcot-Marie-Tooth or Guillain-Barré syndromes. These symptoms tend to manifest in multiple limbs and are more global within each limb. Patients who present with these symptoms should undergo a thorough medical evaluation. Generally mild symptoms are transient and spontaneously resolve. If the pain persists and there are other symptoms, such as paresthesias and weakness, further evaluation and treatment by a hand surgeon should be recommended. The initiation of the evaluation by the primary care physician with radiographs and NCV/EMG studies can shorten the time between presentation, diagnosis, and the institution of treatment.

Compression neuropathies affect up to 10% of the population. As the peripheral nerves travel from the vertebral foramina to their end organs, they pass through several anatomic sites of potential compression. The pathophysiology of compression and neurologic pain can be explained by the localized nerve ischemia and the interference of the axonal transport of metabolic products. The level of compression determines the clinical symptoms. Proximal compression of the nerves as they exit the vertebral bodies produces symptoms in a dermatomal distribution, whereas distal nerve compression produces symptoms in the defined region of the specific nerve(s) that cross multiple dermatomes. Symptoms of intrinsic neurologic dysfunction, eg, metabolic or demyelinating neuropathies, tend to manifest in multiple limbs and are more global within each limb. After the physical examination, the next step in the patient’s work-up should be an electrodiagnostic evaluation. The level and severity of compression can be elucidated by NCVs. Motor dysfunction and muscle denervation due to nerve compression can be elucidated with an EMG. Multiple levels of compression can occur simultaneously at the various sites. This is referred to as a “double crush” phenomenon.

Intrinsic nerve dysfunction may be symptoms of an underlying systemic disease, such as hypothyroidism, rheumatologic disease, diabetes mellitus, and pregnancy. The patient therefore should undergo a thorough medical evaluation. If the hand symptoms are mild and of recent onset secondary to an underlying medical condition, they will often resolve when the underlying cause is treated. However, severe pain, weakness, or paresthesias warrant evaluation and treatment by a hand surgeon, because permanent damage can occur in the absence of timely intervention.

- Paresthesias of the palmar aspect of the thumb, index, and long fingers, and radial aspect of the ring finger.

- Positive Phalen maneuver and Tinel sign at the wrist.

- Thenar atrophy and weakened pinch with long-standing compression.

The carpal tunnel is an anatomic structure located in the proximal part of the hand distal to the junction with the forearm. The carpal tunnel is the space defined by the carpal bones on the radial, ulnar, and dorsal sides with a tough ligamentous structure called the transverse carpal ligament on its palmar roof. The transverse carpal ligament attaches on the radial side to the tuberosity of the trapezium distally and proximally to the tuberosity of the scaphoid and the styloid process of the radius. On the ulnar side, the ligament attaches to the hook of the hamate distally and to the pisiform proximally. The transverse carpal ligament maintains the carpal arch and serves as a pulley for the flexor tendons. Within this space, there are nine flexor tendons (four flexor digitorum superficialis tendons, four flexor digitorum profundus tendons, and the flexor pollicis longus), and the median nerve.

After the median nerve passes through the carpal tunnel, it divides into the digital sensory branches to the thumb, index and long fingers, and to the radial side of the ring finger. The only motor nerve that branches from the median nerve at this level of the wrist is the recurrent motor branch, which provides the motor innervation to the majority of the thenar musculature. This recurrent branch has variable branching patterns, with the most frequent being the branch curling over the distal edge of the ligament (Plate 3).

Carpal tunnel syndrome is the most common nerve entrapment syndrome; up to 1% of all people will develop symptoms during their lifetime. It is more common after the fourth decade of life and occurs three times more often in women than in men. Medical risk factors include diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, hypothyroidism, and renal disease. It may also be associated with any activity that produces repetitive motion and vibration. Controversy exists about whether carpal tunnel syndrome is a work-related entity.

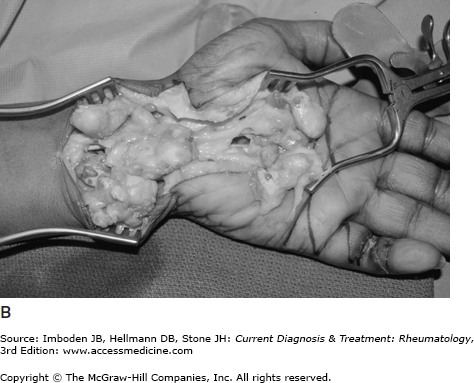

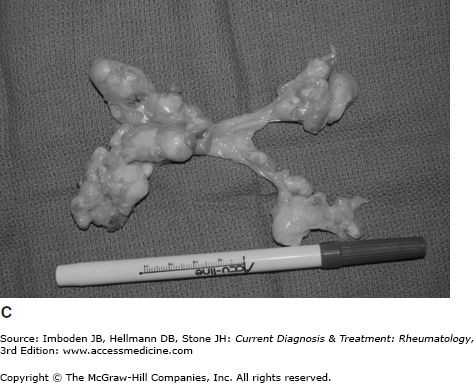

The most common cause of idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome is the inflammation of the tenosynovium of the nine tendons within the carpal tunnel, resulting in the compression of the median nerve within the carpal tunnel. Other causes include space-occupying lesions (ganglion cyst, lipoma, giant cell tumors [Figure 6–2]), trauma, hematoma, and proliferative wrist arthritis. Traumatic causes are often acute and may require urgent surgical decompression.

Figure 6–2.

A: Magnetic resonance image of a giant cell tumor spanning the carpal tunnel. The patient was having carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms with paresthesia of the fingers in the median nerve distribution. B: Intraoperative view of the giant cell tumor in the carpal tunnel. C: The giant cell tumor excised.

The classic symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome include numbness and tingling in the median sensory nerve distribution (thumb, index and long fingers, and the radial side of the ring finger). These symptoms may be worse at night due to the wrist flexion that occurs with the fetal position during sleep. Patients often describe alleviation of the pain when they shake the affected hand or placing the hand in a dependent position, perceiving vascular insufficiency as the cause of the hand feeling cold and numb. Symptoms may be exacerbated during the day when the wrist is hyperflexed or hyperextended, such as with driving or using a computer. With long-standing compression, there can be profound grip and pinch weakness and complete loss of sensation in the affected fingers.

Both hands are visually examined. The thenar muscles in a normal hand should be well developed and full. In mild carpal tunnel syndrome, there should be no change in the appearance of the thenar musculature. With advanced carpal tunnel syndrome, the thenar muscles can atrophy due to decreased innervation of the abductor pollicis brevis muscle by the recurrent motor branch, resulting in a depressed or hollowed appearance (Plate 4). This results in hand weakness and difficulty in thumb opposition to the small finger. Spontaneous fibrillation in the thenar muscles can sometimes be seen.

Sensation in the fingers should be assessed. Light touch perception is done by touching the fingers lightly with either a gauze or a cotton swab. Perception of noxious stimuli is done with either a paper clip or the relatively sharp end of a toothpick. For more sophisticated testing, sensation can be measure by a two-point discrimination test or the Semmes-Weinstein monofilament testing. Grip and pinch strength should be done for baseline measurements. Provocative testing can be done to look for the Tinel sign, Phalen sign, or Durkan sign. A positive Tinel sign is when the patient perceives electrical shooting pains into the distal distribution of the nerve when the nerve is percussed. In the case of the median nerve, the percussion is done over the median nerve at the wrist. If the patient perceives the electrical shocks at the site of the percussion and it radiates into the thumb, index, and long fingers, then this is a positive Tinel sign of the median nerve.

A Phalen test is performed with the patient passively flexing both wrists by touching the dorsal surfaces of one hand to the other dorsal surface. The wrist is held in flexion for 60 seconds. If the patient’s symptoms are reproduced, this is a positive Phalen test. In Durkan carpal tunnel compression test, the examiner’s thumbs are placed over the carpal tunnel over the median nerve just above the carpal tunnel. If the patient has symptoms of carpal tunnel within 1 minute of compression, the test is considered positive. The Durkan test is not widely used.

Despite a classic history, the clinical hand examination may be normal in early stages of carpal tunnel syndrome. The nerve conduction study though should show prolonged motor latencies with slowing of nerve conduction velocities if there is compression. With prolonged median nerve compression, there may be muscle denervations that can be detected with the EMG.

If the cause of the nerve compression is due to a tumor or suspected to be a tumor, an MRI should be ordered (see Figure 6–2). A diagnostic biopsy of the mass is done if required and followed by surgical resection.

Conservative management for idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome should aim at reducing the tenosynovial inflammation and swelling within the carpal tunnel. Splinting and the use of over-the-counter NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, should be the first-line therapy. The patients are fitted with prefabricated wrist splints that maintain the wrist at 5–10 degrees of extension. These wrist splints are available in the hand surgeon’s office or over-the-counter as “carpal tunnel splints.” Splints can also be custom fabricated by the hand therapists. The patients are instructed to wear the splints during the most symptomatic times, which often is during the night when the patients flex their wrist during the fetal sleeping position or during the day when the patient is more active. The patients are instructed on proper ergonomics during the awake and sleeping hours to avoid any positions that cause compression of the median nerve. Approximately one-third of patients managed nonoperatively in this fashion respond favorably.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree