Approach to the Patient with Foot & Ankle Pain: Introduction

The foot and ankle are marvelous biomechanical creations. Tasked with forward propulsion, shock absorption, and providing balance for more than one hundred and twenty million steps in the average lifetime, it is a wonder that more people do not have more problems than they already have with their feet.

It is useful to divide the foot into the following three anatomic regions for evaluation: forefoot, midfoot, and hindfoot. Each region has its own unique pathology. Similarly, when evaluating the ankle it is helpful to consider whether the complaint is generated from an intra-articular or extra-articular source. In either case, a working knowledge of the anatomy is essential.

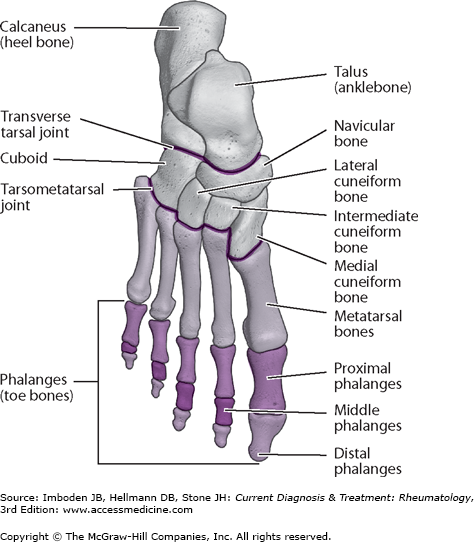

The forefoot includes the phalanges and the metatarsals. The midfoot boundaries include the tarsometatarsal joint (or Lisfranc joint complex) and the midtarsal joints (talonavicular and calcaneal-cuboid joints). The hindfoot consists of the talus and calcaneus (Figure 7–1).

The ankle (tibiotalar) joint is largely responsible for dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of the foot. The joint itself is composed of the distal tibia, the distal fibula, and the talus. Inversion and eversion motion of the foot occurs cooperatively through the subtalar (talocalcaneal), talonavicular, and calcaneal-cuboid joints. The joints in the midfoot region contribute very little to foot motion.

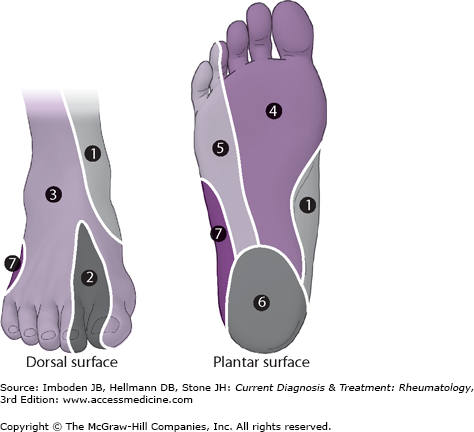

There are five major peripheral nerves that innervate the foot. Three of these run superficial to the fascia (sural nerve, superficial peroneal nerve, and saphenous nerve) and two are deep to the fascia (the posterior tibial nerve and the deep peroneal nerve) (Figure 7–2).

Forefoot Pain

Metatarsalgia is plantar pain under the metatarsal heads or under the “ball” of the foot from abnormal loading. This term is often used incorrectly to describe any plantar forefoot pain and should be reserved for pain localized under the metatarsal heads with loading from standing or gait. Although multiple etiologies of forefoot pain exist, symptoms from metatarsalgia are typically under the second or third metatarsal heads. Careful physical examination reveals tenderness directly under the metatarsal head with less or no tenderness dorsally, with toe motion, or with palpation in the web spaces. The differential diagnosis is extensive but includes stress fracture, metatarsophalangeal joint (MTP) synovitis, Freiberg disease, Morton neuroma, bursitis/neuritis, and either degenerative or inflammatory arthritides of the MTP joints. Metatarsalgia is commonly seen with hammertoe deformities due to plantar displacement of the metatarsal head secondary to tendon imbalance. It is also commonly associated with bunion deformity as increased angulation leads to decreased load bearing by the first ray during gait and transfer of the weight-bearing load to the relatively longer second metatarsal.

- Insidious development of dorsal forefoot pain after increased physical activity or change in shoe wear.

- Pain to direct palpation of the metatarsal.

Metatarsal stress fractures are incomplete metadiaphyseal or diaphyseal breaks that typically involve the metatarsal neck or shaft. Although any metatarsal can be involved, classically these are seen in the second or third metatarsals. Fatigue stress fractures occur with repeated overload of normal bone past its remodeling capabilities or with normal loading in osteoporotic bone. Although most patients with fatigue stress fractures have a history of increased physical activity or loading, this is not always the case.

Metatarsal stress fracture typically presents subacutely; patients often do not have a history of significant trauma. Forefoot pain with ambulation and dorsal forefoot swelling is common. Pain is localized directly over the stress fracture.

Plain weight-bearing radiographs should be obtained. Because early radiographs are often normal, repeat examination in 10 days is warranted if high clinical suspicion persists. MRI can reveal bone marrow edema or occult cortical breaks earlier than radiographs, but repeat examination with a radiograph is the more cost effective strategy.

Treatment consists of immobilization in either a postoperative shoe or fracture boot for up to 4–6 weeks. Weight bearing should be allowed as tolerated but rest is recommended as long as the patient has pain. Patients should take calcium/vitamin D supplementation when appropriate and should limit high-dose glucocorticoids they may delay bone healing in the early stages. Tobacco use increases the rate of delayed or nonunion of the fracture, and smoking cessation is therefore recommended. Close follow-up should be considered because there is a small risk for displacement.

- Increased incidence of central metatarsalgia involving the second and third MTP joints.

- Point tenderness over the metatarsal heads with palpation.

The MTP joint stress syndrome occurs when increased stress from load bearing is transferred abnormally to these joints. Since the second and third tarsometatarsal joints are relatively fixed, these MTP joints are affected most commonly. The first, fourth, and fifth tarsometatarsal joints are in comparison more mobile and are less affected as a result, but sesamoiditis can manifest as metatarsalgia of the first ray. Predisposing factors include synovitis, spondyloarthropathies, and multiple biomechanical alterations of the foot that may predispose to abnormal forefoot loading. Examples of such biomechanical alterations include the cavo varus deformity, Achilles/gastrocnemius contracture, fat pad atrophy, arthritis, posttraumatic deformities. Bunion deformities often lead to second MTP metatarsalgia due to an increased angulation between the first and second metatarsals and decreased relative loading of the first ray with ambulation. Although initially presenting as plantar forefoot pain secondary to inflammation, long-standing metatarsalgia can lead to MTP joint dislocation, stress fracture, and digital deformities (hammer toe, claw toe, cross-over toe).

Pain is described as a dull ache under the plantar forefoot (“ball of the foot”) with symptoms exacerbated by increased activity or the use of high heels that increase forefoot loading. Lesser toe deformities may exist. Morton neuroma must be considered if the patients complain of pain radiating into the toes. Patients typically have point tenderness under the metatarsal heads or at the MTP joint with increased pain with toe motion. If there is no tenderness in the plantar region and the patient reports pain with toe motion, isolated MTP synovitis should be considered. Patients with long-standing symptoms of MTP pain may have joint instability. In such cases, an evaluation for MTP joint subluxation should be performed. The Lachman or vertical load test assesses the stability and integrity of the ligaments and capsular structures. To perform this test, the examiner stabilizes the metatarsal with one hand while lifting the digit at the proximal phalanx dorsally with the other, assessing the patient for joint stability and symptom exacerbation.

Plain radiographs of the foot are usually unremarkable but are essential to exclude other conditions. Weight-bearing radiographs are required.

Treatment consists of shoe wear modification, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and activity modification. Stiff sole shoes and the avoidance of high heels is recommended. Often times a shoe with a rocker bottom may help alleviate symptoms. An orthosis with a metatarsal bar and recess under the metatarsal heads is usually beneficial. Toe strapping may be helpful to limit motion. Glucocorticoid injections should be used sparingly as ligament and capsular weakening and rupture can occur.

- Plantar forefoot pain with possible radiation into the toes.

- Tenderness on compression of the involved web space.

- Presence of a “Mulder click” is highly suggestive of the condition.

Morton neuroma is an entrapment neuropathy of the small interdigital nerves. This is associated with perineural fibrosis and soft tissue swelling. The third MTP interspace is the most common location, although the second is often involved. Rarely are the first or fourth interspaces involved. The hallmark of Morton neuroma is a burning pain radiating into the toes. Patients often complain of plantar foot pain as well and often describe the sensation of “walking on a pebble” or as if their socks were bunched in the forefoot area. Symptoms are often exacerbated with tight shoe wear and high heels and alleviated when barefoot. Compression of the webspace often elicits symptoms. Often the nerve can be subluxed with forefoot compression and dorsal pressure in the interspace (Mulder click) although the sensitivity and specificity of this test is questionable. The clinician should consider other diagnoses if the patient denies any radiating pain into the toes.

Plain radiographs are often normal although are useful to rule out other causes of pain. MRI and ultrasound have limited usefulness, since normal or abnormal radiographic findings do not correlate well with clinical presentation.

Initial treatment consists of shoe wear modification, NSAIDs, and activity modification. If these measure fail, glucocorticoid injection may be considered but there exists a risk of ligament and capsular weakening from repeated use. Recalcitrant cases should be referred for neurectomy.

- Pain, paresthesias, and dysesthesias in the first web space.

- Positive Tinel sign with percussion.

- Pain relief after nerve block.

Deep peroneal nerve entrapment is a compression neuropathy of the deep peroneal nerve. This often occurs more proximally at the anterior tarsal tunnel or distally as the nerve passes over the midfoot. Proximal entrapment occurs when the nerve is affected as it passes under the anterior ankle extensor retinaculum. The anterior ankle extensor retinaculum is a fibrous band of tissue that encases the neurovascular bundle as well as the extensor tendons of the ankle and foot. More distal entrapment can occur as the nerve passes intimately over the midfoot and is often secondary to trauma, scarring, and arthritis or bone spurs.

Patients with deep peroneal nerve entrapment present with pain, paresthesias or dysesthesias isolated to the dorsal first web space (dermatome of the deep peroneal nerve). Ankle and foot plantar flexion, compression or percussion exacerbate symptoms over the site of entrapment (Tinel sign). Increased physical activity, particularly while wearing shoes that increase dorsal pressure on the nerve, also exacerbates symptoms. Most patients have a component of rest pain as well. Late in the disease, weakness of the extensor hallucis brevis may occur. This is heralded by weakness to hallux extension with resistance placed against the proximal phalanx.

Weight-bearing radiographs are important to assess for bone spurring or arthritis, which can lead to nerve compression, and to exclude other etiologies of pain. MRI may be a useful adjuvant to assess for ganglion cysts or other masses that may be causing compression.

Symptomatic treatment includes the use of NSAIDs, rest, and stiff shoes with the avoidance of dorsal pressure. Topical analgesics and medications for neuropathic pain may help. Immobilization and injections should be considered for recalcitrant cases. If all conservative measures fail, referral for decompression and neurolysis is warranted.

- Limited or absent motion of the first MTP joint.

- Radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis.

Hallux rigidus is secondary to degenerative arthritis of the first MTP joint. Patients may have a history of trauma, although this may seem benign. Patients complain of pain with attempted weight bearing and with activities that require increased motion at the MTP joint. Pain is centered over the hallux MTP joint and is worse with walking barefoot, on the beach or with high heels. Patients may notice decreased symptoms when wearing stiff soled shoes. Patients may report tenderness with pressure due to bone spurring and often complain of nerve symptoms into the hallux secondary to mild compressive neuropathy of the digital nerves from swelling or spurs. Patients often confuse their condition with a bunion deformity due to the appearance of a “bump” on the great toe. Hallux rigidus can coexist with hallux valgus deformity. A personal and family history of gout or other crystalline arthropathy should be elicited. The swelling associated with hallux rigidus is often less severe, less acute, and with less redness than that seen in podagra.

Hallux dorsiflexion should equal lesser toe dorsiflexion and limited dorsiflexion with elicitation of pain is the hallmark sign of hallux rigidus. Plantar flexion is often limited and can cause pain due to the stretching of soft tissues over the prominent dorsal spur. With advanced arthritis, the grind test (axial loading of the joint) is positive. Patients often have tenderness with palpation of the spurs.

Weight-bearing plain radiographs reveal joint-space narrowing, sclerosis, subchondral cysts, spurring, and sometimes malalignment. Periarticular erosions are classic for a gouty arthropathy.

Initial treatment consists of rest, NSAIDs, activity modification, and shoe wear modification. Stiff sole shoes, rocker bottom shoes, and the avoidance of high heels are recommended. A rigid orthosis, such as a Morton extension, can help alleviate symptoms. Surgery is indicated if conservative measures fail.

- Lateral deviation of the hallux with medial bunion causing pain.

Hallux valgus (bunion) consists of lateral deviation of the hallux with medial MTP joint irritation and is associated with shoe wear, female gender, and hyperlaxity conditions. Hallux valgus results from angular deformity at multiple joints in the foot and is not a result of simple medial bone growth. Patients typically complain of pain directly over the bunion that is often exacerbated by shoe wear and hallux motion. With more advanced conditions, patients may complain of forefoot pain due to metatarsalgia or commonly associated lesser toe deformities such as hammer and cross-toe deformities. Patients may also complain of toe numbness due to the stretching of the medial digital nerves. Patients have tenderness most often over the bunion itself but can have pain with MTP motion and metatarsalgia.

Weight-bearing plain radiographs are essential for diagnosis.

Initial conservative treatment should consist of shoe wear modification (open toe shoes or those with a wide, tall toe box), NSAIDs, and activity modification. Toe straps and spacers may be helpful although they do not permanently correct or limit the progression of hallux valgus. Night bunion splints have no utility and may be harmful, particularly in the neuropathic patient or those with vascular compromise. Orthotics may help with symptoms secondary to metatarsalgia but have a limited role in the treatment of hallux valgus. When conservative measures fail and the patient has continued pain and disability, surgery may be indicated. Surgery is not indicated for cosmetics in the absence of pain.

Subtalar Joint & Midfoot Disorders

Subtalar motion is responsible for inversion and eversion of the hindfoot and helps assist ambulation on uneven ground. Midfoot motion, although relatively small compared to ankle or subtalar motion, is a complex coupling of abduction, adduction, rotation and translation of smaller joints and helps translate hindfoot motion to the forefoot during gait.

Multiple conditions can interfere with hindfoot and midfoot motion including trauma, posttraumatic arthritis, coalitions, and rheumatologic conditions such as osteoarthritis and inflammatory arthropathy. Congenital or acquired malalignment conditions such as pes planus (flat foot) and cavo varus foot deformities (high arches) inherently create limitations in subtalar and midfoot motion by altering normal foot kinematics.