Chapter 7 Application – Integrative healthcare

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a move towards the integration of CAM into mainstream healthcare. The emergence of new societies, academic chairs, forums, publications, referral networks, integrative clinics and centres of integrative healthcare are testament to this claim. Yet despite the level of progress in this area, few have questioned whether such a shift is appropriate or acceptable, and even fewer have explored how or why this approach should be implemented. This chapter will address these concerns by examining the merits and limitations of integrative healthcare and, further to this, highlight how these strengths may help to improve some of the shortfalls of a conventional system of care; it will also address the drawbacks of independent practice. But before addressing these issues, the term ‘integrative’ needs to be understood.

Defining integrative care

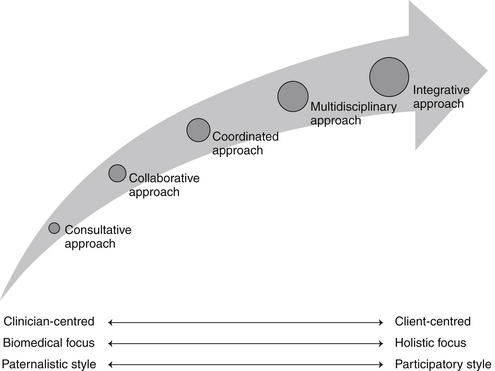

Over the past few decades there has been a shift in the way healthcare has been delivered, from the traditional consultative, paternalistic and independent practice model, to the multidisciplinary approach and, more recently, to the integrative healthcare model. As one moves to the right of this consultative–integrative healthcare spectrum (see Figure 7.1), it is clear that these approaches become more holistic, complex and patient-centred as practitioner autonomy, hierarchy and reliance on the biomedical model decrease.1 What this spectrum fails to differentiate, though, is integrative medicine from integrative healthcare, which are distinctly different, non-interchangeable approaches to care.

Integrative medicine is defined by Rees and Weil,2 for instance, as ‘practising medicine in a way that selectively incorporates elements of complementary and alternative medicine into comprehensive treatment plans alongside solidly orthodox methods of diagnosis and treatment’. What this definition implies is that integrative medicine is professionally exclusive because it applies only to the uptake of CAM by biomedical practitioners. By failing to consider other aspects of assimilation, such as the inclusion of CAM practitioners within mainstream settings, such a term holds little relevance to CAM practice. A more appropriate and inclusive term is ‘integrative healthcare’.

Integrative healthcare is defined as a multidisciplinary, collaborative and patient-centred approach to healthcare in which the assessment, diagnostic and treatment processes of alternative and conventional medicine are equally considered.3 This clinical approach also ‘combines the strengths of conventional and alternative medicine with a bias towards options that are considered safe, and which, upon review of the available evidence, offer a reasonable expectation of benefit to the patient’.4 Put simply, integrative healthcare is a comprehensive and holistic approach to healthcare in which all health professionals, including biomedical and CAM professions, work collaboratively in an equal and respectful manner, to safely and effectively meet the needs of the patient and the community.

Conventional system of healthcare

Existing systems of healthcare are diverse and complex but are generally based on a similar purpose, that is, the treatment of disease and infirmity.5 A more effective system of healthcare also needs to focus on preventing disease and promoting wellbeing,5 as well as providing care that is individualised, holistic and patient-centred. Given the reductionist, fragmented, standardised and disempowering treatment often provided in conventional systems of healthcare at present,6 particularly in secondary care settings, it is necessary that these systems be carefully evaluated and subsequently improved.

These systems of healthcare can be evaluated in terms of acceptability, efficiency and equity.7 Acceptability for instance, refers to patient, community and provider acceptance of the system. System inefficiencies, quality of care, personal experience, beliefs and preferences are all likely to impact on this outcome.

The service, administrative and economic efficiencies of the healthcare system, or performance of the system, is influenced by a number of factors, such as skill mix, funding, resource allocation, infrastructure, system priorities, adaptability to change and outcomes of care.7 Even though many healthcare systems have attempted to improve system efficiency through the introduction of casemix funding (an outcome-based funding model),8 there are still ongoing issues relating to continuity of care, unavoidable costs, evaluation of service outcomes, adaptability to system level changes and the balance between medical and non-medical services.7,8

The final component of system evaluation is equity, which is concerned with indiscriminate access and outcomes of healthcare services.7 Even though universal and equitable access to healthcare may be improved through the provision of national subsidy schemes, such as the Australian Medicare system, in most cases these public programs only subsidise the delivery of medical, hospital and laboratory services.5,9 One exception to this is the Australian Medicare-funded enhanced primary care program, which allows eligible persons to gain access to a limited number of allied health services, albeit via referral from a general practitioner. The subsidisation of pharmaceutical agents through the pharmaceutical benefits scheme (PBS) is another long-standing national subsidy program,9 although, once again, it only applies to specific medical treatments.

These examples illustrate that in Australia at least, the mainstream system of healthcare has been designed to perpetuate the interests of certain key stakeholders, such as medical practitioners and pharmaceutical companies.5 The exclusion of other pertinent health services (such as naturopathy and massage therapy) and products (including most herbal medicines and nutritional supplements) from these subsidisation schemes indicates that this system is, by definition, unequitable. The following paragraph exemplifies this point further.

In Australia, health consumers have access to a wide range of CAM services, yet only a proportion of these services can be financially reimbursed through private insurance companies and none of the products prescribed by CAM practitioners are eligible for reimbursement. For consumers with chronic or complex care needs, there is limited access (i.e. maximum of five allied health services per year) to publicly funded CAM services, specifically, chiropractic and osteopathy. Thus, for the many individuals who wish to access CAM services but are uninsured, have an acute complaint or have long-term care needs, they will have to pay for these services out of pocket. According to a recent Australian survey of CAM consumers, these out-of-pocket expenses can range from AUD$1 to AUD$650 per month (mean = AUD$21.23) per user. This translates to AUD$1.3 billion per annum at the national level.10

The escalating cost of maintaining the current system is unlikely to be efficient, cost-effective or sustainable in the long term.5 Measures that improve the efficiency, acceptability and equity of existing systems of healthcare need to be implemented so that the needs of all individuals can be better met.5 These strategies also need to offer a significant cost–benefit to the system. One strategy that may fulfil these requirements is the development of an integrative system of healthcare.

Movement towards integration

Over the last decade, there has been rising interest and increasing use of natural medicines and complementary practitioner services. This trend not only applies to consumers, but also to practitioner groups: orthodox clinicians now use and endorse a wide range of complementary therapies.11,12 The scientific community is also pushing healthcare towards a more integrative approach,13 with a number of integrative clinics, hospitals and academic centres now available across the globe, and pharmacies and pharmaceutical companies now selling a range of conventional and complementary medicines. Evidence also suggests that CAM practitioners are being accepted as legitimate health service providers.14 One could argue that the legitimisation of CAM services, together with the integration of these services into mainstream care, may be influenced by the increasing biomedical content and evolving curricula of undergraduate CAM courses, the closer alignment of these courses with the scientific paradigm and subsequent improvements in biomedical language proficiency among CAM practitioners, but the impetus for these changes in practice remains unclear, although many factors have been proposed.

The shift towards CAM could be explained in part by mainstream medicine’s inability to adequately address a number of patient needs,15–17 including the need for respect, holism, choice, autonomy and time. The erosion of client–practitioner relationships, the dependence on invasive technologies and the primary focus on disease might also contribute to the move away from orthodox practice.17 So, a change in patient needs and beliefs may be a factor driving the increasing use of CAM.16,18

Individuals with chronic and life-threatening conditions may also turn to CAM in order to find a solution to their problem. One reason why these patients may try CAM is that conventional practice, and the system it is situated in, does not allow for high-quality prevention or treatment of chronic disease.19–23 Key stakeholders may need to consider an integrative model of practice in order to address the shortfalls of both the current system of healthcare and the medical model.17

Medical pluralism, or the utilisation of more than one form of healthcare, can increase the number of interventions made available to patients and, in turn, provide the client with a number of different treatment perspectives. As opposed to the paternalistic and universalistic model of healthcare that currently exists, the more pluralistic and individualised system of integrative care may foster collaboration between CAM services and mainstream practitioners, improve client outcomes and more effectively meet the needs of patients.21 At present, however, the existing system of healthcare is the antithesis of pluralistic.15

The right to be informed about a range of therapeutic options from a variety of disciplines is a right of every individual. Yet, since most conventional clinicians are not sufficiently knowledgeable about CAM and preventative healthcare11,20,24–26 and many CAM practitioners might not be familiar with the myriad orthodox treatment approaches,27 a number of clinicians may not be equipped to inform patients about an appropriate range of therapies. Practitioner bias or lack of knowledge about other modalities could also deprive patients of suitable treatment options and, in effect, compromise the patient’s ability to make an informed decision about their care.24 Since practitioners have an obligation to inform patients about treatments that are well supported by evidence,28 strategies that facilitate this process are in the best interests of the client. The inclusion of CAM content within medical degrees and the increasing biomedical content within CAM courses is a critical step towards addressing this problem.

Problems with integration

In spite of the push towards an integrative system of healthcare, many issues need to be considered before accepting this approach (see Table 7.1). The first of these relates to the different paradigms of CAM and orthodox medicine. Since integrative healthcare is not just about adding therapies to a discipline, but is also about accepting a different mindset,15 this is of some concern, as many practitioners who are well trained and experienced in their respective therapies may be unwilling to accept new healthcare philosophies or new challenges to convention.29 In fact, conventional clinicians who simply choose a few isolated therapies to incorporate into their practice may be seen ‘as orthodox biomedical cherry picking from the complementary field, [in order] to supplement conventional treatment’.30 The same principle also applies to CAM practitioners who choose to adopt complementary therapies for which they have no formal training, for example, a chiropractor choosing to dabble in herbal medicine or a naturopath dabbling in acupressure. In either case, ignoring the philosophical foundations of a treatment may deem the approach as simply another tool and not an independent therapy in its own right.

Table 7.1 Challenges facing the integrative healthcare movement

| Interprofessional issues |

< div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|