Chapter 19 Ankylosing spondylitis and the seronegative spondyloarthopathies

KEY POINTS

There are a group of disorders collectively known as the spondyloarthropathies: ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis and Reiter’s disease, and enteropathic arthritis

There are a group of disorders collectively known as the spondyloarthropathies: ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis and Reiter’s disease, and enteropathic arthritis Clinical features of the spondyloarthropathies can overlap and can include low back pain and stiffness, restriction of chest expansion, inflammation of the sacroiliac joints, enthesitis, peripheral joint involvement and extraarticular manifestations (e.g. inflammation in the eye)

Clinical features of the spondyloarthropathies can overlap and can include low back pain and stiffness, restriction of chest expansion, inflammation of the sacroiliac joints, enthesitis, peripheral joint involvement and extraarticular manifestations (e.g. inflammation in the eye)INTRODUCTION

This chapter will describe the group of disorders collectively known as the spondyloarthropathies a group of interrelated but heterogenous conditions (Boonen et al 2004). The treatment of these conditions will be considered using ankylosing spondylitis (AS) as the exemplar. A number of different terms have been used to describe the same group of conditions including spondarthritides (Moll 1987), spondylarthropathies (Hakim & Clunie 2002), seronegative spondlyloarthritides (Olivieri et al 2002) and spondyloarthropathies (Wordsworth 2002). The last term has been adopted for use in this chapter. The chapter will cover ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis and Reiter’s disease, and enteropathic arthritis.

There is a degree of disagreement over the grouping and classification of the conditions within the group collectively known as the spondyloarthopathies (SpA) (Nash et al 2005). It was once thought that different entities of the SpA group represent variable expressions of the major characteristics of the same disease. Patients with SpA commonly test negative for rheumatoid factor hence the term ‘seronegative’. In addition there is a common but variable association with the genetic factor HLA-B27, although some evidence suggests that there are also close associations with other HLA gene factors in this group (Said-Nahal et al 2002). There are racial variations in HLA B27 distribution with corresponding variations in the prevalence of SpA within the same racial grouping. Box 19.1 lists the common features associated with the SpA group of conditions.

ANKYLOSING SPONDYLITIS

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is an inflammatory disease that affects the axial skeleton causing characteristic inflammatory back pain, which can lead to structural and functional impairments and a decrease in quality of life (Braun & Sieper 2007). Fibrosis and ossification of ligament, tendon and capsule insertion (the entheses) mainly in the regions of the intervertebral discs and sacroiliac joints are hallmarks of the condition (Hakim & Clunie 2002). Inflammatory changes can also occur in the cartilagenous joints of the axial skeleton (symphysis pubis, discovertebral junction and manubrio sternal joint). The disease can sometimes affect the hip joints.

Initial changes usually begin in the sacroiliac joints, lumbosacral and thoracolumbar joints with later change progressing throughout the axial skeleton. The inflammatory process results in ligament ossification and the formation of vertical outgrowths of bone called syndesmophytes. Progressive syndesmophye growth results in bony union between adjacent vertebrae. In moderate and severe cases there is progressive and irreversible stiffening of the vertebral column (Fig. 19.1). The disease has an insidious onset and typically continues over many years. Left untreated it will usually result in severe spinal deformity and functional limitation.

There is lack of universal agreement over the current classification system for AS (Braun et al 2002). A range of diagnostic criteria have been developed although in the early stages of the disease a person might be diagnosed as having AS without fulfilling all the criteria. The following is a description of the Modified New York criteria (Van der Linden et al 1984):

PREVALENCE

Estimates of AS prevalence have been reported between 0.1–0.2% (McVeigh & Cairns 2006), 0.25–1% (Calin 2004) and 0.5% (Wordsworth 2002). This means that whilst patients with AS are commonly seen within rheumatology units AS is relatively uncommon in the community as a whole. The ratio of males to females ranges from 3:1 (Symmons & Bankhead 1994), 2.5:1 (Calin 2004) and 5:1 (McVeigh & Cairns 2006).

MAIN FEATURES OF AS

PSORIATIC ARTHRITIS

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic heterogeneous disease whose pathogenesis is unknown, although genetic, environmental and immunological factors play major roles (Mease & Goffe 2005). It is a progressive condition and without appropriate treatment results in irreversible joint destruction with resultant disability and functional loss. Psoriasis is a skin disorder affecting 2% of the population characterised by plaques of hyperkeratonic skin commonly on extensor surfaces and in the scalp and occasionally more generalised (Veale & Fitzgerald 2002). The skin disease usually pre-dates the arthritis but in as many as 25% of subjects the arthritis might be synchronous or pre-date the skin disease (Wordsworth 2002). If there is a family history of psoriasis a patient can be diagnosed as having psoriatic arthritis without skin disease being present.

The prevalence of PsA is not well known (Boonen at al 2004). Estimates range from 0.04%– 1.2% (Gladman 2006). Sixty percent of patients with PsA will be HLA-B27 positive (Wordsworth 2002). It affects men and women equally, usually between the ages of 20 and 40 years (Hakim & Clunie 2002). PsA may present in one of a number of clinical patterns, the following is based on the description by Gladman (2006):

Points 1 and 2 are the commonest presentations. There is some doubt about how strictly PsA exists within these clinical forms (Marsal et al 1999) although four of the five categories can assist in establishing a differential diagnosis (see Ch. 16 to contrast with the features of rheumatoid arthritis).

The radiographic (x-ray) features of established psoriatic arthritis

REACTIVE ARTHRITIS AND REITER’S DISEASE

Reactive arthritis (ReA) is a sterile inflammatory arthopathy, which may develop after bacterial or viral infection. A healthy but genetically predisposed individual develops it following an immune system response to an infection. In the gut this is commonly Shigella, Salmonella or Campylobacter infection, and in the genital tract Chlamydia trachomatis (Toivanen 2000). Typically 60–80% of patients with ReA are HLA-B27 positive (Yu & Fan 2001). Reactive arthritis differs from infectious (septic) arthritis in that the infectious organism cannot be cultured from the joint fluid or synovium.

Reiter’s disease (or Reiter’s syndrome) is currently the term applied to a reactive arthritis displaying specific signs. These are the classic triad of arthritis, urethritis (urethral inflammation) and conjunctivitis (Yu & Fan 2001). The common clinical features are listed below.

Common clinical features (Yu & Fan 2001)

ReA tends to be a self-limiting condition and 90% of patients recover in the first year (Yu & Fan 2001). It is very important to treat the underlying cause of infection as this settles the arthritis. Treatment is also directed at the joint manifestations of the disease. When reactive arthritis develops as the result of sexually acquired infection it can be called sexually acquired reactive arthritis (SARA). Treatment guidelines are provided for SARA by the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (2001). It is always important to consider the implications of discussing the history of SARA with the patient when members of their family or friends are present.

ENTEROPATHIC ARTHRITIS

Enteropathic arthritis is an inflammatory arthritis of peripheral joints and axial skeleton associated with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Peripheral arthritis is relatively common in inflammatory bowel disease and its incidence is 10% in ulcerative colitis and 15–20% in Crohn’s disease (Jewell 1993, Shearman & Finlayson 1989, Wollheim 2001). Axial skeletal involvement has been reported as having an incidence of 10–15% in ulcerative colitis and 15–20% in Crohn’s disease (Wollheim 2001). Peripheral arthritis tends to be asymmetrical and affect the larger joints (hips, knees, ankles and wrists). If there is a spondylitis (inflammation of spinal joints) or sacroiliitis the course of the disease is independent of the bowel condition. In addition to joint features some patients also experience enthesopathies and inflammatory eye conditions.

ASSESSMENT

This section will outline the principles of assessing the spondyloarthropathies and will relate this to intervention by the therapist. Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is the prototype of the spondyloathropathies (Braun et al 2002) so this section will focus on assessing AS. The principles of assessing peripheral joint arthritis in SpA and peripheral joint arthritis of other diagnostic types are almost identical so the reader should refer to Chapters 3 and 16 for further detail.

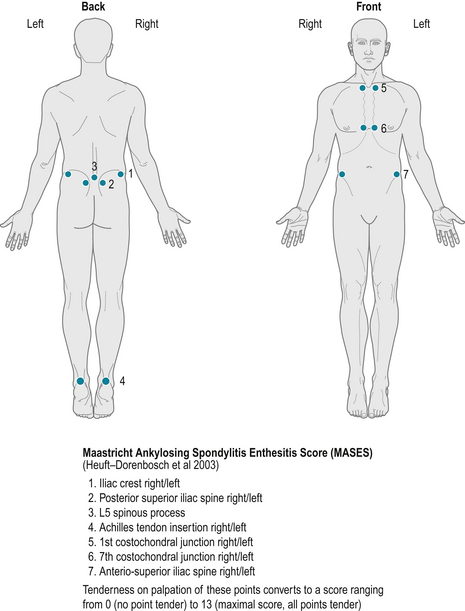

The four clinical features of AS, enthesitis, axial involvement, peripheral articular disease, and extra articular features should be assessed (Dougados & van der Heijde 2002). Some areas of potential extra articular problems (skin, eyes, gut) are outside the normal remit of therapists’ roles and require other members of the team to assess and manage them. The assessment and treatment of foot and ankle problems arising from arthritis or enthesitis is sometimes undertaken by a podiatrist rather than a physiotherapist (see Ch. 13). Box 19.2 highlights the elements of a therapist’s assessment.

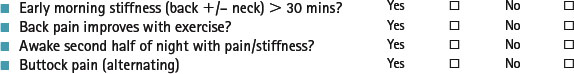

It is important for the therapist to remember the context in which they are undertaking their assessment and to gather data relevant to the purpose of the assessment. Often, time will be a factor affecting the amount of data that can be collected but selective use of validated outcome measures can make the process more efficient and effective (see Ch. 4). The emphasis of assessment is likely to vary in different situations; a potential case of undiagnosed SpA is likely to need a different approach to a person newly diagnosed with AS or assessment undertaken as part of monitoring long term follow up. Therapists can facilitate the rapid referral of suspected SpA to rheumatologists as recommended by the Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance (ARMA 2004). This is especially important in situations of patient self referral for therapy where the patient’s GP has not been consulted. A systematic, analytical process is required to differentiate other forms of spinal pain from AS (Fruth 2006). A simple screening tool, such as the one used in a therapy service in South Devon, may be useful in identifying potentially undiagnosed individuals with early AS presenting directly to therapy services (Box 19.3). Such screening tools warrant further evaluation in clinical practice.