CHAPTER 28 Anesthesia, Pain Management, and Early Discharge for Partial Knee Arthroplasty

The implementation of specialized clinical pathways in joint replacement has simultaneously decreased the length of hospital stay while significantly decreasing complications.

The implementation of specialized clinical pathways in joint replacement has simultaneously decreased the length of hospital stay while significantly decreasing complications. We have developed newer perioperative anesthesia and rehabilitation protocols and combined them with a minimally invasive approach to partial knee replacement in order to hasten recovery and perform outpatient partial knee replacement.

We have developed newer perioperative anesthesia and rehabilitation protocols and combined them with a minimally invasive approach to partial knee replacement in order to hasten recovery and perform outpatient partial knee replacement. Using these newer protocols with a minimally invasive approach to partial knee replacement, we have found that patients recover faster and outpatient partial knee replacement is not only possible, but has become routine for our patients.

Using these newer protocols with a minimally invasive approach to partial knee replacement, we have found that patients recover faster and outpatient partial knee replacement is not only possible, but has become routine for our patients.Historical Perspective

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty was originally popularized in the 1970s, promising minimal bone sacrifice and the potential ease of future revision to a total knee arthroplasty, if required. Unfortunately, an incomplete understanding of appropriate indications and surgical techniques, combined with flawed early prosthetic designs, resulted in a high rate of failure. Subsequently, unicompartmental knee arthroplasty was all but abandoned in the United States by the late 1980s. Fortunately, renewed interest in the concept was initiated by Repicci and colleagues,1,2 who in the 1990s described a minimally invasive technique for unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Subsequently, unicompartmental knee arthroplasty has increased in usage secondary to a combination of interest in less invasive knee arthroplasty1–3 and reports from multiple centers of survivorship that rivals that of total knee arthroplasty in appropriately selected patients.4

In the past decade, efforts have been made to improve the short-term outcomes of both total knee arthroplasty and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty with respect to pain control and early functional recovery with the implementation of minimally invasive surgical techniques.5–10 The evolution of many orthopedic procedures has had this progression. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction has evolved from an inpatient to an outpatient procedure. In addition, spinal diskectomy has also had similar changes over the past decade. As in these procedures, minimizing soft tissue trauma is one part of a greater protocol that has led to decreased inpatient needs and, at our institution, the now commonplace outpatient unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. A comprehensive perioperative approach is essential to allow same-day discharge of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty patients. This paradigm shift involves not only the patient and surgeon, but also the patient’s family, the hospital, anesthesia team, therapists, and nursing staff. A successful protocol and pathway includes pain management, decreasing medication side effects, and accelerated therapy that is delivered in a timely fashion.

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative planning occurs in many stages and is the most important part of the process. It begins long before the day of surgery and includes much more than the historic medical clearance and implant choice that we have become accustomed to. The main components are planning, perioperative education, teamwork, and follow-through. The entire plan is customized for each individual patient and is created in the office at the time the patient decides to have surgery. After choosing the surgery date, the patient’s medical history is carefully scrutinized to identify relevant problems such as cardiac, pulmonary, thromboembolic, anticoagulation, and any other issues that may require more thorough preoperative investigation or an altered postoperative management. All patients attend a comprehensive educational class prior to surgery. During the same visit to our medical center for the teaching class, the patient’s medical clearance appointments and laboratory tests are scheduled, as well as an appointment to donate a unit of autologous blood. Each patient is given a complete packet of information in the office when they sign up for surgery. The contents follow a clear and logical format—these are summarized in Box 28–1.

Box 28–1 Summary of Patient Information Packet

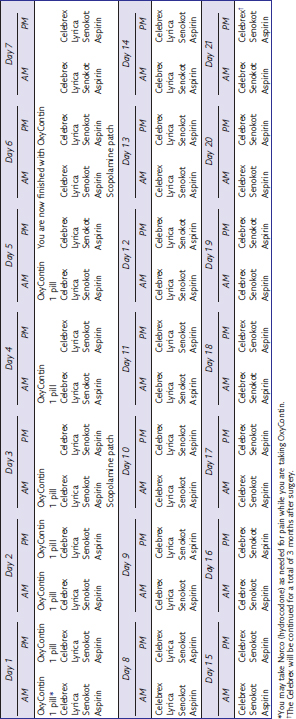

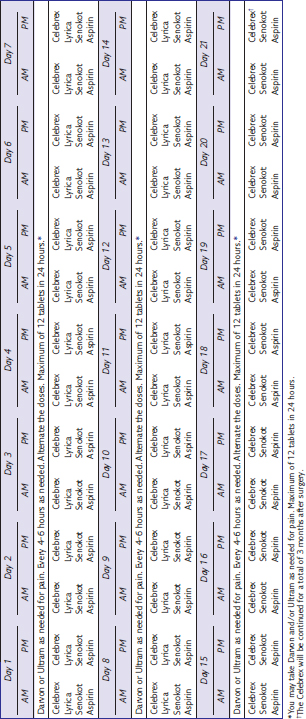

The most significant hurdle to outpatient partial knee arthroplasty is effective pain management. Much of the difficulty stems from patient fears and beliefs. A significant portion of the preoperative class therefore focuses on pain control strategies. The patients receive their postoperative pain medications from the hospital pharmacy at the time of the class to avoid any unnecessary delays the day of surgery. We employ a long-acting narcotic for baseline pain control, a short-acting breakthrough narcotic, and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory. In addition, we proactively reduce side effects such as nausea and constipation. The postoperative medication strategy is outlined in Tables 28–1 and 28–2. Table 28–1 is the routine table we use for our patients, while Table 28–2 is for the elderly patient or the patient who cannot or will not take oxycodone (OxyContin). Furthermore, it is difficult to predict the most appropriate dose of oral narcotic pain medication, even when considering the patient’s weight and age. Therefore, all patients are asked to take one dose of the strongest pain medication they will take the week before surgery and to report any side effects. The postoperative dose can then be modified appropriately. The stool softener and antinausea medication are initiated prior to surgery and continued as shown in Tables 28-1 and 28-2. Finally, the patients are given two additional sheets that give an overview (Table 28–3) and a detailed view (Box 28–2) of their medications so that they understand what to take, when, and why.

Table 28–2 Postoperative Medication Sheet for Elderly Patients or Patients Who Cannot Take Oxycontin

Table 28–3 Overview of Postoperative Medication Protocol

| Long-acting narcotic | OxyContin (oxycodone HCl, controlled release; Purdue Pharma L.P., Stanford, CT) |

| Short-acting narcotic | Norco (hydrocodone/acetaminophen) |

| COX II anti-inflammatory | Celebrex (celecoxib; Pharmacia/Pfizer, Chicago, IL) |

| Antinausea agent | Scopolamine patch |

| Stool softener | Senokot S (to start 2 days prior to surgery) |

Box 28–2 Medication Explanation for Patients

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree