Anatomy for the Electromyographer

Denise L. Davis

Ernest W. Johnson

Introduction

Have an anatomy text nearby! This textbook does not replace it. Know where things are in the anatomy text.

In our many years of testing the competence of electromyographers in various settings, a major deficiency has been anatomic knowledge of even basic nerve and muscle locations. There are over 400 skeletal muscles in the body for assessment by electromyography (EMG). The electromyographer must know surface anatomy well and furthermore should check with the anatomy text frequently for reinforcement of anatomic landmarks. Chapters 8 and 9 in this text include photographs to reinforce your learning of surface anatomy in order to improve your EMG techniques.

Basic kinesiologic knowledge also is essential to activate the muscle being investigated. Movements are represented on the motor cortex and produced by groups of muscles, not by individual muscles. In a recumbent person, it is very difficult to elicit a maximal contraction in a two-joint muscle, but it is much easier to have that full effort on a single-joint muscle. For example, study recruitment in the soleus (ankle joint only) instead of the gastrocnemius (knee and ankle) with plantarflexion, and evaluate the vastus medialis (knee joint only) rather than the rectus femoris (hip and knee) during knee extension.

Tables 1-1 and 1-2 include simple and useful guides for motor spinal nerve root motor innervation of the muscles of upper and lower limbs.

When exploring a large muscle for an involved root problem, one should consider the embryologic pattern to reduce sampling error. This pattern is that as one moves from cephalad to caudad, from proximal to distal, from anterior to posterior, and from medial to lateral, then one moves downward (caudal) in the levels of spinal cord root innervation. Similarly, the pattern of sensory innervation goes from medial to lateral, anterior to posterior, and proximal to distal as the roots descend along the spinal cord. The amplitudes of the sensory and motor responses in Table 1-3 can be used to evaluate axon loss caused by proximal injury of their nerves or roots (1).

More exhaustive lists are at the end of this chapter for reference (Tables 1-4,1-5,1-6), but Tables 1-1,1-2,1-3 should be memorized.

For suspected radiculopathy, it is always more efficient and accurate to select a small muscle for better EMG sampling. An example includes using the tensor fascia lata for L5 instead of the gluteus medius; both have three root levels, L4, L5, and S1. Not only can the muscle be sampled more efficiently at rest, but muscle activation is usually easier to carry out in a small muscle (see Fig. 8-73). The relatively anterior position of the tensor fascia lata also allows it to be explored in the

supine position, which is helpful when the patient cannot easily be moved.

supine position, which is helpful when the patient cannot easily be moved.

Table 1-1 Upper Limb Motor Innervation | |

|---|---|

|

Table 1-2 Lower Limb Motor Innervation | |

|---|---|

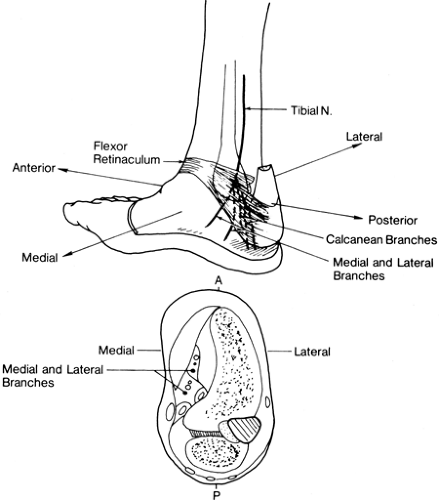

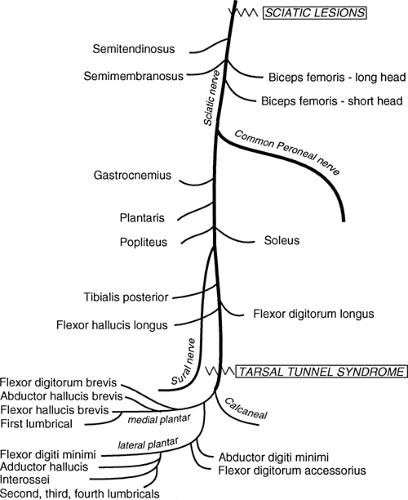

Figure 1-2 • Sciatic and tibial nerve anatomy showing branches and common sites of focal neuropathy. |

Table 1-3 Sensory and Motor Nerve Conduction Study Innervations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

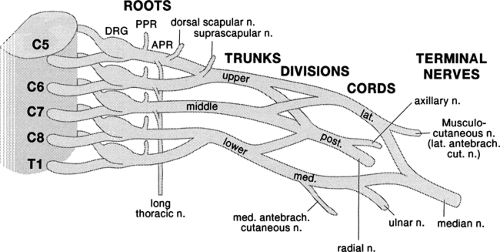

Figure 1-3 • Brachial plexus with demonstration of cervical roots and spinal nerves to the trunks and other components. |

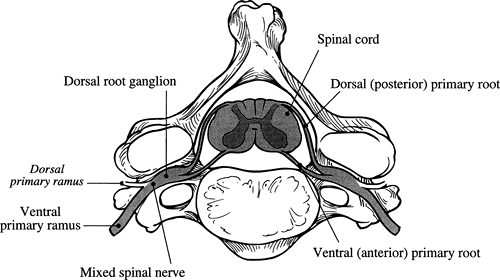

Figure 1-4 • Relationships between the spinal cord, the roots, and the ventral and dorsal rami. Note that the dorsal root ganglion is at the intervertebral foramen. |

It is a common mistake to avoid needle EMG exploration of the intrinsic muscles of the feet because of the notion that positive waves and fibrillation potentials will be invariably present because of the trauma the feet are exposed to based upon their anatomic location. This is incorrect (2): these muscles are excellent sources of EMG abnormalities in peripheral neuropathies, but they are also difficult to study because of their small size. It is easy to advance the EMG needle electrode into the endplate and record endplate potentials as positive waves, a phenomenon that can be confusing to the electromyographer who is unaware of this risk of a false-positive result.

Special Areas of Concern to the Electromyographer

Cervical Paraspinal Muscles

These are properly explored much more caudally than has been appreciated. For the muscles innervated by the posterior primary ramus of C6, the needle electrode must be inserted at the level of the tip of and lateral to the spinous process of the C7 cervical vertebra. C7 is at least 2 cm more caudal and C8 is at the mid-scapular border. This is because the superficial paracervical muscles (semispinalis cervicis) attach to the midline spinous processes and descend at a slight angle to insert below on ribs and the lateral processes (Fig. 1-10). Remember that the needle must first pass through the trapezius before reaching these paraspinal muscles.

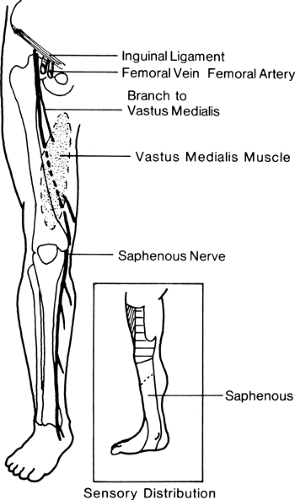

Figure 1-9 • Anatomy of the saphenous nerve showing its origin from the distal femoral nerve.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|