Chapter 2 Amputees

Introduction

• The student or novice physiotherapist may treat the ‘primary’ and/or the ‘established’ amputee.

• Where there is no on-site specialist physiotherapist available for supervision and guidance it is important that the therapist knows when, where to seek specialist support, e.g. via a regional prosthetic centre or specialist physiotherapist in the acute setting.

• This volume covers the treatment of the adult amputee with acquired lower limb amputation, with some reference to the adult upper limb amputee.

• Advice on the treatment of the child with acquired amputation or congenital absence should be sought from regional specialist centres.

• Treatment planning requires a holistic, integrated, multidisciplinary approach, enabling effective exchange of information with all involved in the treatment of the patient.

• To encourage patient adherence to rehabilitation, SMART goals for treatment must be agreed initially, between the patient and the team members involved in the patient’s management.

• Ongoing evaluation by the physiotherapist (and other team members) of the amputee’s ability to achieve treatment goals during the early treatment stage will assist in determining the amputee’s suitability for prosthetic referral.

• Physiotherapy treatment is defined by assessment findings. Physical, personal, social and environmental factors will influence the plan and determine how attainable rehabilitation goals will be.

• The amputee and physiotherapist should consider goal setting as something to be done in partnership and the plan should include short and long-term goals.

• The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO 2001) model can assist the evaluation of the assessment findings (Geertzen 2008).

• It is recommended that the ‘SOAP’ format is used for recording treatment.

• Appendices 2.1 and 2.2 provide additional material for students.

Physiotherapy treatment goals

denotes specific treatment rationale for UL physiotherapy treatment.

denotes specific treatment rationale for UL physiotherapy treatment.

The prevention of postoperative complications

• This follows the same principles used for any postsurgical patient and applies to all age groups and causes of amputation.

• The amputee will be an inpatient from 1 week to several weeks, depending on the amputee’s health, the service and setting and their home environment circumstances.

• The early postoperative stage is normally within the first week postsurgery.

• The aim within this week is for the patient to progress to attending the therapy gym.

Pain management

Early management

• Pain after amputation is common and to be expected.

• Communication and co-ordination of treatment with other members of the MDT is essential and the timing of physiotherapy treatment must coincide with pain control.

• The physiotherapist should have an understanding of prescribed pain medication and side effects (BNF 2010).

• The amputee experiencing significant postoperative pain will find it difficult to co-operate and engage with physiotherapy treatment, therefore the physiotherapist should provide reassurance and explanation of underlying postoperative pain in the residuum (RLP).

• The patient should be alerted to the possible presence of phantom limb sensation (PLS) which may include phantom limb pain (PLP) (Broomhead et al 2006).

• Information about PLS should be provided by health professionals with appropriate knowledge and training (Mortimer et al 2002).

• It should be explained to the patient that PLS is a normal response and consequence of amputation surgery, which handling, exercise and medication will help to reduce.

• This is important for the safety of the amputee who may sense their amputated limb as being present and could unconsciously attempt to weight bear through it, resulting in a fall.

• Handling the residuum helps to desensitise nerve endings, helps the remodelling of the homunculus and contributes to the amputee’s adjustment to their new body image (Ramachandran and Hirstein 1998).

• ‘Stump handling’ enables the amputee to apply early individual control over the management of their pain and it is important to reassure the amputee that gentle handling will not harm the wound.

• Stump handling along with daily observation is important at all stages of rehabilitation and must become part of normal daily routine for the amputee post discharge to check for skin changes resulting from pathology, prosthetic fit or positioning.

• Active exercises will encourage resolution of postoperative oedema, which can cause pain.

• Appropriate positioning of the residuum to avoid prolonged and excessive flexion must be emphasised – the patient will instinctively want to flex their residuum if it is painful, therefore maintaining full range and a good resting position is essential and must be reinforced.

Tip!

The physiotherapist must ensure nursing colleagues reinforce effective positioning and handling. A pillow should not be placed under the residuum. The transtibial amputee must use a stump board when in a wheelchair (Figure 2.1).

• Wound healing must be monitored daily by a team member; the physiotherapist should take the opportunity to observe the wound.

Ongoing management

• The amputee may continue to experience either RLP or PLP, or both.

• Where RLP or PLP persists, investigations should be made to identify the cause, e.g. infection, vascular insufficiency, soft tissue injury, referred pain, including joint pain, or breakdown in the myodesis.

• If pain is related to wound breakdown, physiotherapy should be carried out with caution. Exercising may provide some distraction from the pain.

• Where wound healing is compromised and contributing to pain, the use of laser therapy has been reported to be effective (Baxter 1999).

• The physiotherapist must be vigilant in monitoring and evaluating the amputee’s pain and communicating this with relevant colleagues, irrespective of the stage of rehabilitation.

• Assessment findings may indicate interventions including:

• Reference to a ‘pain pathway’ can facilitate clinical reasoning and support the decision-making processes for a team approach to pain management (Appendix 2.3).

• Progressing with a general exercise programme and use of an early walking aid (EWA) will assist in the management of an amputee’s phantom sensation and/or pain (Barnett et al 2009).

Improve functional mobility and balance

Early management

• Where practical, and with MDT collaboration, treatment should be on a daily basis.

• All amputees irrespective of level, age or pathology, should be suitably dressed to participate with physiotherapy, i.e. in day clothes, ideally loose-fitting skirts and trousers with elastic tops, a comfortable and good-fitting sock and shoe with non-slip sole for the single amputee when ready to transfer from bed to wheelchair.

• Lie to sit practise will routinely form part of chest treatment and will aid all ADLs.

• Rolling, same rationale as for lie to sit. Incentives for basic functional movements are comfort, preparation for transfers and engaging in active exercises.

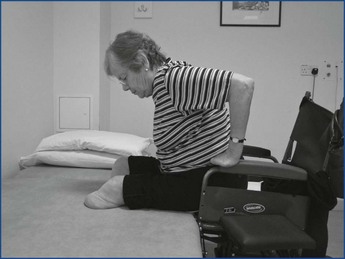

• Dynamic sitting balance is essential for transfers, dressing, toileting and ultimately walking, irrespective of level, UL or LL.

Routine balance exercises

• Challenging the amputee to reach outside base of support.

• Rhythmic stabilisations in sitting.

• Rhythmic stabilisations in sitting over the side of the bed/plinth with the remaining foot on the floor. Progress to removing contact with the floor.

• Use of sit-fit cushion, e.g. throwing/catching of ball.

•  The UL amputee finds dressing difficult and clothes without buttons or zips make this easier.

The UL amputee finds dressing difficult and clothes without buttons or zips make this easier.

•  If the UL amputee has had an amputation of their dominant hand functional activities such as dressing, toileting, eating and writing will need to be practised with the remaining limb.

If the UL amputee has had an amputation of their dominant hand functional activities such as dressing, toileting, eating and writing will need to be practised with the remaining limb.

•  Where possible the residual limb should participate in these normal functional activities and a range of devices can assist this, e.g. non-slip mats and a simple gauntlet.

Where possible the residual limb should participate in these normal functional activities and a range of devices can assist this, e.g. non-slip mats and a simple gauntlet.

•  The bilateral UL amputee will need specific assistive tools to assist ADLs.

The bilateral UL amputee will need specific assistive tools to assist ADLs.

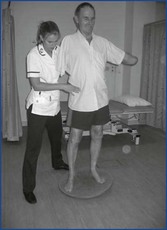

•  A high level or bilateral amputation can affect balance. Balance exercises in sitting, standing and walking should be practised (Figure 2.2).

A high level or bilateral amputation can affect balance. Balance exercises in sitting, standing and walking should be practised (Figure 2.2).

Wheelchair provision

• Occupational therapists traditionally provide wheelchairs and cushions, in some situations it can be the physiotherapist’s responsibility.

• The amputee and/or carer will need to be instructed how to use the wheelchair, including use of brakes and footplates (Broomhead et al 2006).

• All LL amputees, irrespective of age, should be provided with a loan wheelchair on the first day postoperatively.

• A standard 8 L wheelchair (17 inches × 17 inches (43 cms × 43 cms) seat size) is suitable for most adult amputees.

• In some cases a bariatric (heavy-weight) wheelchair is required for the larger amputee.

• Two- to three-inch cushions are standard.

• Where amputees are at high risk of developing pressure areas a pressure-relieving cushion is necessary.

• Bilateral and bariatric amputees need special assessment and provision.

Transfers

• This is an essential requirement for independence and meeting criteria for prosthetic rehabilitation.

• In some instances amputees will not be able to initiate independent transfers; they may be apprehensive, in discomfort or unable to follow appropriate instructions.

• A manual handling risk assessment should be carried out to identify appropriate assistive devices, e.g. sliding boards, hoists.

• All amputees need to be supervised until assessed as safe to transfer independently.

Tip!

The recommended transfer procedure for a single amputee is the standing pivot:

Tip!

All bilateral amputees should be taught ‘sideways’ and ‘forwards backwards’ transfers.

• All transfer procedures can be applied and progressed in relation to setting, e.g. toilet, car.

Ongoing functional ability and balance

Core exercises

• Core exercises have an important role in the treatment of all amputees, UL and LL, whether they progress to rehabilitating with a prosthesis or remain as an independent wheelchair user.

• Despite limited research into the benefits of ‘core stability’ exercises in amputee rehabilitation, it is felt that core stability is essential when using a prosthesis or wheelchair.

• Progression with these exercises will be dependent on the amputee’s cognition, exercise tolerance and ultimate level of activity.

• The independent wheelchair user will benefit from simple mobilising and strengthening exercises (PIRPAG 2005).

• Working closely with OT colleagues, treatment should focus around achieving good dynamic sitting balance to enable independent ADLs and transfers.

• To progress this, more challenging balance exercises can include:

• The prospective limb wearer will benefit from all the above and should be further progressed to incorporate treatments that challenge their balance in an ever-decreasing base of support.

Maintain and increase joint range

Early management

• When the amputee is ready to attend the therapy gym, provided it is practical and safe to do so, he/she should be encouraged to make their own way in their wheelchair.

• Active exercises for the remaining and residual limb maintain joint range, improve circulation and wound healing, reduce residual oedema and prevent postoperative complications, e.g. deep vein thrombosis.

• It is important for the amputee to appreciate that the responsibility for practising exercises is theirs for achieving and maintaining functional mobility and independence.

• Frequent exercise practice should be encouraged, i.e. daily exercise sheets designed specifically for the patient can facilitate commitment to exercise.

Tip!

For examples of standardised exercises for lower limb amputees refer to Physiotherapy Inter Regional Prosthetic Audit Group exercises (PIRPAG 2005).

• The same principles of exercise apply to the UL amputee:

Active exercises for the UL amputee should concentrate on all movements of the shoulder joint and shoulder girdle, i.e. elevation, depression, protraction and retraction, as these are important to enable the amputee to operate a prosthesis

Active exercises for the UL amputee should concentrate on all movements of the shoulder joint and shoulder girdle, i.e. elevation, depression, protraction and retraction, as these are important to enable the amputee to operate a prosthesis The bilateral UL amputee may have to use their lower limbs, chin, neck and trunk to perform some ADLs and therefore maximising active ROM of all these joints is essential.

The bilateral UL amputee may have to use their lower limbs, chin, neck and trunk to perform some ADLs and therefore maximising active ROM of all these joints is essential.Prevention of contractures

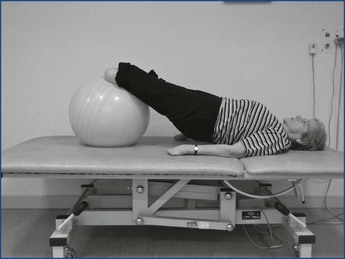

• The promotion of active stretching through positioning and the adaptation of certain exercises will assist in preventing contractures (Figure 2.6).

• Encourage the transfemoral amputee to lie supine each day, to prevent hip flexion and abduction contracture following prolonged sitting or as a consequence of pain.

• For transtibial amputees the use of a ‘stump board’ on the wheelchair will help prevent a knee flexion contracture.

•  There is a tendency for the UL amputee to acquire a posture of internal rotation of the glenohumeral joint, cervical lordosis and side flexion to the affected side; trunk side flexion to the affected side with minimal arm swing (of the residuum); and trunk rotation in walking.

There is a tendency for the UL amputee to acquire a posture of internal rotation of the glenohumeral joint, cervical lordosis and side flexion to the affected side; trunk side flexion to the affected side with minimal arm swing (of the residuum); and trunk rotation in walking.

•  Encouraging early attention to posture in sitting, standing and walking will help prevent loss of range and contractures.

Encouraging early attention to posture in sitting, standing and walking will help prevent loss of range and contractures.

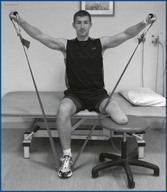

Maintenance and increase in muscle strength

• Considerations for progressing exercise will include the level and cause of amputation, PMH, age and goals.

• Exercises should be designed and graded to achieve progression, incorporating strengthening, joint mobility and endurance.

• The amputee needs to have good endurance of both muscles and cardiovascular system in preparation for prosthetic mobility (Waters and Mulroy 2004).

• The older amputee will require an exercise programme of a more repetitive nature, whereas the younger amputee will require greater variation, challenge and resistance training (Velzen et al 2006).

• Techniques and equipment include:

Tip!

The physiotherapist must be aware of the risk of overuse injuries when setting treatment plans.

Oedema management

• Early control of oedema is important as it relates to many treatment goals, e.g. wound healing, pain management, successful prosthetic fitting and functional mobility.

Early oedema management

• Approaches include elevation and correct positioning postoperatively, i.e. supine on the bed without a pillow under hip or knee, in addition to consistent use of stump board with wheelchair for the transtibial amputee.

Use of compression therapy

• There must be caution when applying compression therapy.

• During the first week wound dressings are kept in place by ‘TubiFast’, a lightly elasticated material, which exerts gentle compression (Mölnlycke 2010).

• There are different sizes of TubiFast for different levels of amputation, e.g. the ‘blue line’ is most commonly used for transtibial amputees.

• There is no current evidence to indicate when to start using ‘compression socks’.

• Practice varies as to who decides if and when it is indicated, it may be the physiotherapist, the vascular nurse specialist, the surgeon or the rehabilitation consultant.

• A compression sock should be used in preference to elastic bandages (Broomhead et al 2006).

• The type of compression is decided according to assessment findings, wound healing, presence of infection, vascularity and patient compliance (Van Ross et al 2009).

• Where a compression sock is indicated, the correct size is a prerequisite, e.g. the ‘Juzo’ sock includes manufacturer’s instructions for measuring to ensure the correct size.

• Additional advice and precautions for their use should be sought from regional prosthetic centres.

• The amputee must understand the correct use and application.

Ongoing oedema management

• The presence of oedema will continue to fluctuate for some time, in some cases up to a year or more.

• This can be due to pathological or metabolic causes, e.g. cardiac disease, poorly controlled diabetes.

• Oedema may persist because of the patient’s own management, e.g. a lack of compliance with use of stump board and/or compression therapy.

• Amputees who choose to hop rather than use a wheelchair are more likely to present with fluctuating oedema.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Walking as balance allows.

Walking as balance allows.