Chapter 2 Amputee Rehabilitation

Introduction

• Amputation is the removal of a limb or part of a limb by surgery or trauma.

• Distinction must be made between those with acquired amputation through surgery or trauma and those with congenital limb deficiency.

• A student or novice physiotherapist who works in amputee rehabilitation will have the opportunity to acquire specific amputee-related knowledge and skills, e.g. oedema control, gait analysis and re-education and prosthetic management. Additionally they will be able to apply and develop musculoskeletal knowledge alongside communication skills, problem-solving and multidisciplinary team (MDT) working.

• The student or novice physiotherapist may assess and treat the primary amputee and/or the established amputee (LLIC 2010).

• Where there is no on-site specialist physiotherapist available for supervision and guidance it is important for the therapist to know when and where to seek specialist support, e.g. via a regional prosthetic centre.

• This chapter will cover the assessment of the adult amputee with acquired lower limb amputation, with some reference to the adult upper limb amputee.

• Advice on the assessment of the child with acquired amputation or congenital absence should be sought from regional specialist centres.

Amputations, a brief history

• Amputations have been carried out throughout history and until the advent of anaesthesia, improved surgical techniques, control of blood loss and effective infection control in the 19th century the mortality rate amongst amputees was high.

• The history of prosthetics can be traced back to 1000 bc, with manufacturing and function remaining basic until the 16th century.

• Throughout history warfare has resulted in accelerated prosthetic developments. Materials, design, function and patient comfort have evolved and been refined as technology has advanced (Bowker and Pritham 2004).

Causes of amputation

• Current demographic data are based on amputees referred to specialist prosthetic rehabilitation centres (Limbless-statistics, 2012).

• Currently there are no national data for all amputations performed in the UK, nevertheless it is estimated that a small number of primary amputees are not referred for prosthetic rehabilitation including amputees who have been assessed by health professionals where prosthetic mobility is considered unsafe or inappropriate.

• In some cases amputees choose not to achieve prosthetic mobility, irrespective of ability.

Consequently, according to Limbless-statistics, 2012 approximately 5000 amputations are performed annually in the UK and referred for assessment for prosthetic rehabilitation, with over 90% of these being lower limb (LL).

Context, United Kingdom

• The number of persons with amputation (the amputee) in the UK – 62 000 (Limbless-statistics, 2012) – is small relative to the total population, i.e. approximately 9 per 100 000, in comparison to approximately 180 stroke patients (per 100 000) (ONS, 1994–1998). The likelihood of every undergraduate student or novice physiotherapist experiencing amputee rehabilitation is therefore small.

• Most amputees receive early rehabilitation as in-patients in an acute hospital setting and form part of a physiotherapist’s caseload that includes non-amputee patients. Depending on the cause of amputation the amputee may be managed on a surgical, orthopaedic or care of the elderly ward and this may be for a prolonged period. Exceptions to this are a vascular unit within a hospital or a specialist rehabilitation ward attached to a prosthetic rehabilitation unit in a disability service centre (DSC).

• Physiotherapists are well placed as key health professionals in amputee management since initial contact can be prior to amputation surgery, in the community or later in the care pathway at review and follow up of the ‘established’ amputee. Irrespective of the setting, guidelines recommend that physiotherapists specialised in amputee rehabilitation be responsible for the physiotherapy management of amputees (Broomhead et al 2003, 2006). A holistic multidisciplinary approach is advocated at all stages of rehabilitation from pre-operative assessment through to prosthetic discharge (Broomhead et al 2003, 2006). At all stages patients’ and carers’ wishes must be considered.

• Following amputation the common goal for most amputees is to achieve functional independence, ideally using a prosthesis. Amputees face many challenges, particularly physical and psychosocial ones which can change with age and acquired conditions affecting potential for rehabilitation, mobility and overall function (Schoppen et al 2003). Physiotherapy assessment is indicated at several stages during rehabilitation and at further and often unrelated times during the life of an amputee.

Assessment

Preoperative physiotherapy assessment

• Recommended where practicable, as this provides an opportunity to observe and note joint contractures, muscle weakness or gait deviations, often present if a patient has had a prolonged period of pain and immobility.

• The physiotherapist can demonstrate equipment, advise on exercises to reduce and/or prevent weakness and prevent contractures.

• Information gained from assessment can be shared with medical colleagues to facilitate the decision process regarding level of amputation and early post-operative management.

• This assessment also offers the potential amputee the opportunity to discuss any concerns and ask questions.

Postoperative physiotherapy assessment

• Usually performed routinely postoperatively, preprosthetically, as part of prosthetic rehabilitation, as part of prosthetic review or following further amputation surgery or acquired pathology.

• Aspects of the assessment are similar to other areas within a physiotherapist’s scope of practice, e.g. an amputee with a musculoskeletal problem would have the same tests performed prior to local soft tissue treatment. An amputee with a neurological condition would have the same assessment of balance, tone and function as performed for a patient managed in a neurological rehabilitation setting.

• The interpretation of physiotherapy assessment defines the goals for treatment, including suitability for prosthetic rehabilitation.

• Ongoing evaluation involving the use of valid, outcome measures, is critical to achieving successful patient outcomes.

Prosthetic assessment

• Following surgery the majority of amputees are referred for prosthetic rehabilitation at their local DSC of which there are 43 in the UK.

• Most will receive their initial prosthetic treatment at the centre as outpatients and will continue their prosthetic rehabilitation at their local hospital or via community services.

• However not all amputees referred to DSC will be fitted with a prosthesis.

• Physiotherapy assessment findings contribute to the MDT decision regarding an amputee’s suitability for this stage of rehabilitation.

General considerations

Age

• The incidence of lower limb amputation increases with age. The average age of a patient requiring a first amputation is 69; 28% of all new referrals to prosthetic centres in 2006 were over the age of 75.

• Unlike LL amputees, most UL amputees are in the younger age groups which reflects the aetiology of the condition, i.e. mainly trauma. Three in every five UL referrals were aged between 16 and 54 years (Limbless-statistics, 2012).

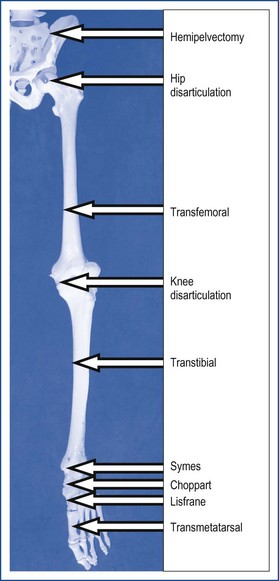

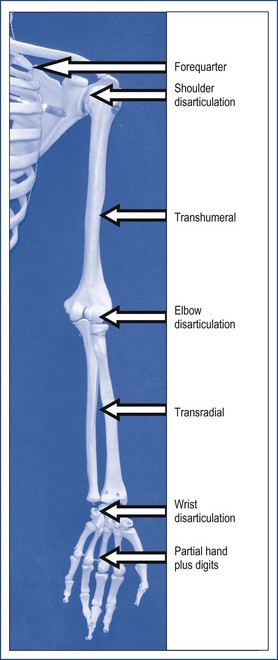

Levels of amputation

• The levels of amputation of the upper and lower limb are shown in Figures 2.1 and 2.2 and the incidence of the amputations at these levels is listed in Box 2.1.

Box 2.1 Causes and incidence of amputations in the lower and upper limb (Limbless-statistics, 2012)

Lower Limb (LL)

Upper Limb (UL)

• Patients with (UL) amputation account for only 5% of the total amputee population, and the cause is mostly traumatic (53% of cases).

• Other causes of UL amputation include:

• Congenital deformity accounts for approximately 3% of all patients with limb absence

• A total of 4,574 lower limb and 215 upper limb amputations were recorded in the United Kingdom in 2006/07.

Mortality

• Perioperative mortality rates are related to level of amputation, cause of amputation, age and co-morbidities (Engstrom and Van de Ven 1999).

• Recent figures from the Vascular Society of Great Britain quote a perioperative mortality rate ranging from 10% in transtibial amputees to 24% at transfemoral level.

• Data indicate 50–60% survival at 2 years and 30–40% at 5 years (vascular cause of amputation).

Additional information to consider

• Anatomy of the lower and upper limbs

• Pathology of causes of amputation, associated conditions and complications including:

• Specific investigations prior to amputation surgery:

• Examples of vascular intervention (Beard et al 2009)

• Depending on the location and extent of the vascular disease the following may be options

• Amputation surgical techniques (Smith et al 2004), e.g.

• Other investigations include

• Pain – causes and influencing factors include, infection, joint pain, psychological (Engstrom & Van de Ven 1999; Ehde et al 2000; Hanley et al 2004, 2006)

• Gait, i.e. normal gait (Whittle 2007)

• Grieving process (Fischer 2009)

• Multidisciplinary team approach (Ham et al 1987; Stewart & Jain 1993; Pernot et al 1997)

• Prosthetics, i.e. basic examples and fit of prosthesis (Smith et al 2004).

Considerations immediately prior to undertaking an assessment

• Type of surgical anaesthesia used – general versus spinal or chemical block.

• Primary or established amputee.

• Timing, e.g. postoperative, preprosthetic or prosthetic stage of rehabilitation, prosthetic review.

• Pain control. Ensuring that pain is adequately controlled will enable the amputee to engage effectively in the assessment process and allow the therapist to perform a thorough and accurate assessment.

• Therapy/MDT assessment approach, i.e. profession-specific or joint assessment (e.g. OT and PT). Joint assessments reduce repetition for the amputee and can enrich the quality of the information obtained.

• Next of kin and/or carers. In some instances it is necessary to seek permission from others, e.g. for children, vulnerable adults.

• Awareness of prior or associated assessments.

• Access to existing reports, e.g. home access visit. These can help target assessment questions.

• Environment, e.g. gym setting with adjustable plinth, ward and hospital bed, home.

• Patient to be suitably dressed for assessment.

• Removal of footwear to allow inspection of remaining foot.

• Acknowledge cause and associated physical problems, e.g. neural damage or fractures.

• Awareness of feelings of anxiety and loss, sadness and sometimes depression. There may be associated family or personal loss. In cases of severe trauma some amputees may experience post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

• Early identification of cognitive problems will influence the extent of assessment, goal setting, treatment plan and outcomes of rehabilitation. If not performing a joint assessment early referral to an occupational therapist or psychologist may be required.

Subjective assessment

Past and relevant medical history

• Diabetes – diabetic control and management, previous healing rates; presence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and/or glaucoma, renal disease.

• PVD – presence and manifestation of intermittent claudication; effects on remaining limb.

• Osteoarthritis – limitations of movement, joint replacement affecting pre-amputation mobility.

• Rheumatoid arthritis – active/burnt out; joint deformities; hand function will be important for ability to transfer and don a prosthesis.

• CVA – important factor in determining level of amputation and likely outcomes.

• THREAD (Thyroid disorders, Heart problems, Rheumatoid arthritis, Epilepsy, Asthma or other respiratory problems, Diabetes).

• General health, e.g. recent weight loss/gain.

• Previous surgical history, e.g. vascular/orthopaedic reconstructive surgery, other amputation surgery or general surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree