Adductor and Iliopsoas Release

Tom F. Novacheck

DEFINITION

Psoas and adductor contractures are most common in cerebral palsy but can occur in any neuromuscular condition owing to disuse, muscular imbalance, or spasticity.

The degree of contracture varies depending on the patient’s age and the severity of neuromuscular dysfunction.

Detecting hip flexion contracture (psoas) is challenging.

The challenge for the adductors is deciding which muscles to lengthen and how much lengthening to do.

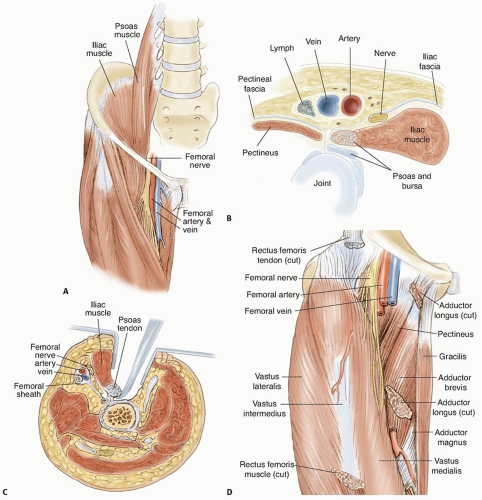

ANATOMY

The psoas is part of the primary hip flexor group, the iliopsoas.

The psoas muscle originates from the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae. The muscle belly passes over the sacrum into the pelvis (FIG 1A).

At the level of the pelvic brim (superior pubic ramus), the intramuscular tendon can be found.

At this level, the psoas lies underneath the muscle belly of the iliacus. The femoral neurovascular bundle is superficial to the iliacus (FIG 1B,C).

The psoas and iliacus tendons combine below the level of the pelvic brim to form a common tendon that inserts on the lesser trochanter.

The adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, and gracilis are clinically considered the adductor group of the hip. Their origins arise from the pubic and ischial rami as well as the pubic tubercle and they insert medially on the femur (adductors) and proximal tibia (gracilis) (FIG 1D).

The adductor longus has a tendinous origin, the gracilis has a muscular fascia, and the adductor brevis and magnus have muscular origins.

The anterior branch of the obturator nerve lies in the interval deep to the adductor longus and superficial to the adductor brevis, whereas the posterior branch of the obturator nerve lies in the interval deep to the adductor brevis and superficial to the adductor magnus.

PATHOGENESIS

Hip flexion and adduction contractures develop over time due to the following:

Lack of typical functional activities

Muscular imbalance between these muscle groups and their antagonists, the hip extensors and abductors, due to either weakness of the antagonists or spasticity of the agonists

A hip flexion contracture is typical at birth and persists in infancy up until the time the child begins to stand and walk. In an older child who has not achieved standing and walking ability, a hip flexion contracture therefore may represent a persistence of the normal fetal alignment.

At birth, the normal amount of hip abduction range of motion is 60 to 90 degrees, significantly greater than the expected range of motion of adults.

Appropriate musculotendinous length develops during growth as the muscle responds to bone growth and stretch associated with typical childhood activities such as walking, running, and playing. Growth occurs at the musculotendinous junction through the addition of new sarcomeres.

Contractures of these structures do not allow the joint to achieve normal positions for daily activities.

NATURAL HISTORY

Contractures, if severe and persistent, can lead to hip subluxation, hip dysplasia, and ultimately hip dislocation.

Hip dysplasia and especially hip dislocation are most common with more severe cerebral palsy (quadriplegia, minimally ambulatory or nonambulatory, Gross Motor Function Classification System [GMFCS] IV and V) and in L2- or L3-level myelodysplasia because muscular imbalance at the hip is most severe (innervated hip flexors and adductors, paralyzed abductors and extensors).

In more functionally mobile children with cerebral palsy (GMFCS I, II, and III), psoas and adductor contractures may lead to anterior pelvic tilt, excessive pelvic motion, and lack of hip extension in terminal stance and contribute to crouch.

Although a scissoring gait is commonly considered to be due to adductor contractures, this visual appearance most commonly results from the combination of hip and knee flexion with internal hip malrotation due to excessive femoral anteversion.

In long-standing cases, hip dysplasia can lead to degenerative arthrosis.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Physical examination methods include the following:

Hip flexion-extension range of motion: Normal walking function requires 7 degrees of extension beyond neutral pelvic position. Therefore, even small contractures limit functional range of motion, shorten step length, and induce compensatory movements.

Hip abduction-adduction range of motion: Maximum abduction range of motion during typical walking is only 5 degrees. Therefore, even moderate limitations of hip abduction range of motion may not have functional significance (unless spasticity is also present). Normal hip development may not occur if abduction range of motion is limited.

If resistance is felt as the hip is extended and abducted, spasticity is present. Increasingly severe spasticity increases

the risk of development of subsequent contracture. For ambulation, spasticity (even in the absence of contracture) can limit movement.

Hip flexion and hip adduction strength are tested in the supine position. Lengthening a contracted and weak muscle may adversely affect function. Weak, antagonistic muscle groups (hip extensors, hip abductors) predispose to flexion and adduction contractures and contribute to muscle imbalance.

When examining a child for hip flexion contracture, the examiner should not be misled by the presence of a knee flexion contracture that prevents full extension of the leg. This can be avoided by moving the patient to the side of the examination table and allowing the lower leg to drop off the side of the table.

Femoral anteversion must also be examined for and ruled out.

Accurately identifying and controlling pelvic position is crucial for evaluating hip extension and abduction range of motion.

For the nonambulatory patient, the examiner should look for hyperlordosis and a flexed, adducted, internally rotated hip. For the ambulatory patient, observation of gait may show hyperlordosis, limited step length, scissoring gait, or crouch gait.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

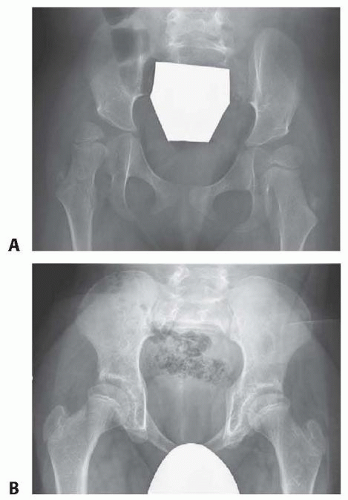

Supine anteroposterior (AP) pelvis radiograph (FIG 2)

Pelvic obliquity

Adducted hip

Lordotic pelvis

Varying degrees of hip dysplasia

Gait analysis may reveal the following:

Pelvic obliquity with affected side elevated

Limited hip abduction range of motion in late stance and during swing phase

Excessive anterior pelvic tilt with or without excessive pelvic range of motion

Limited hip extension range of motion in terminal stance

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Hip dysplasia or dislocation

Knee flexion deformity

Hip abductor or extensor weakness

FIG 2 • AP pelvis radiographs. A. Common findings of coxa valga (although femoral anteversion cannot be eliminated as a possibility): break in the Shenton line indicating subluxation, incomplete femoral head coverage, pelvic obliquity (right side elevated), mild windswept hips (right adducted), and mild acetabular dysplasia (right > left). B. In this case, severe hip flexion contractures result in anterior pelvic tilt. The AP pelvis radiograph results in an inlet view (obturator foraminae are not visible).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access