I. BASIC PRINCIPLES AND DATA. Acute injuries to the hand and wrist are common. Obvious reasons for this fact stem from use of the hand as a working tool in sometimes dangerous environs (e.g., as an object holder immediately adjacent to a power tool) and the all too frequent use of the arm as brake (fall onto an outstretched arm). A patient’s general health characteristics may play an important role in determining the frequency and outcome from such accidents (e.g., diabetics with originally reduced sensation and ongoing reduced blood supply/immune function and osteoporosis with reduced skeletal strength). There are several issues to be considered with all patients.

A. Date of last tetanus immunization. One should consider the possibility of skin compromise with injuries to the hand and wrist. Even without obvious laceration, penetration of infectious organisms into the subcutaneous tissue has been known to occur. The effects of infection from one such organism (tetanus) are largely preventable. Consequently, verify the status of tetanus immunization in all patients whom you are treating for hand or wrist trauma. Do not assume that this has been resolved by a prior examiner.

B. Injury site characteristics. These may alter your treatment choices. For example, a fracture with a nearby clean laceration from a sharp object can often be managed as though the skin had remained closed, whereas the same fracture associated with a minimal but contaminated (farmyard or sewage) puncture into the fracture hematoma must first be thoroughly irrigated. Thus, the first key characteristic is to establish the extent of the skin injury and to specifically determine whether any external injection of organisms deep into the skin surface is likely to have occurred. In the case of burns (cold or hot), knowledge of the depth of the skin injury is important. It is important to be specific when describing wounds. Adjectives used to modify established terminology (e.g., “severe,” “bad,” or “not bad”) should be avoided. Use phrases or classification with known meaning whenever possible.

Helpful adjectives used in characterizing a wound include the following:

- Open or closed: Used most commonly in association with a fracture. If the skin is open to a fracture, it is considered open. This same phraseology is important in treating lacerations close to joints and some tendon injuries.

- Clean or contaminated: Generally, a kitchen knife would be considered clean as compared with a saw blade picked up from a farmyard workbench.

- Tidy or untidy: The margin of a laceration can be so ragged as to prevent repair. In the hand (the same applies to the foot and face), this can preclude tensionless wound closure and thus necessitate advanced wound management methods.

- The Gustilo classification specifies soft-tissue injury severity in conjunction with an open fracture and is as follows.1,2

Type I represents a low-energy injury with an open lesion of less than 1 cm.

Type II represents an open laceration greater than 1 cm with moderate soft-tissue injury.

Type III represents an open laceration greater than 1 cm with extensive soft-tissue damage and is further subdivided into three types:

Type IIIA: adequate soft-tissue coverage

Type IIIB: inadequate soft-tissue coverage

Type IIIC: associated with arterial injury

C. Patient’s habits and addictions. Without doubt, the most important habit to be aware of is the patient’s habit of following medical advice. This is particularly important in children, and the emergently consulted physician has a known responsibility to enable timely follow-up care. Most hand and wrist injuries requiring consultation from an orthopaedic specialist will need early (2 to 14 days) follow-up, and failure to ensure this care may result in disability. Other habits of importance include the following:

- Tobacco use disorder. In addition to being an established diagnosis (ICD-9 = 305.12), this problem will impact bone healing (known) as well as other tissues (skin, tendon, nerve) (suspected).

- Recreational drug use. Impaired patients will place stresses on casts and dressings such that the medical repairs may fail. In some circumstances, hospital admission with appropriate consults is required.

D. Systemic illness. Illness that compromises immune function is a common reason for delayed recovery after hand/wrist injury. In addition, diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or advanced osteoporosis will impact the result from injury and the type of treatment that can be chosen.

II. HISTORY

A. Where and how did the injury occur? As noted earlier, record the location of the injury and its mechanism. This is important for two basic reasons. First, you need to know the cleanliness of the wound and how much energy was applied to the tissues. Second, you need to record the where (work, home, motor vehicle accident, etc.) and how (an allegedly defective tool, a reported assailant, etc.) because the first examining document will be used henceforth as the “truth.” Thus, your written history should contain few adjectives and only known facts.

B. How did the patient become aware of the injury? Some injuries will present after the suspected injury occurred. In these instances, recording additional facts related to the patient’s presentation is important.

C. Pain

- Location. Be specific. Use anatomic descriptors. Try to avoid use of “medial and lateral” and numbering the digits (due to misinterpretations). The second finger is not the index but the middle. Thus, do not use number references for fingers as too many physicians and most lay people mistake the index for the second finger (which it is not). Use the following terms: radial and ulnar; dorsal and volar; thumb, index, middle, ring, and small finger.

- Qualities. Phrases such as “really bad pain” are meaningless. Words such as burning, radiating, and tingling may be helpful in detecting/isolating a nerve injury, whereas words such as deep, constant, and throbbing may be associated with an infection.

D. Numbness

- Location (similar to C.1). Describe the anatomic location of the numbness using precise words (e.g., the radial border of the ring finger). These phrases will hopefully be anatomically possible and serve to isolate the nerve difference. Patients describing anatomically unlikely numbness are occasionally seeking secondary gain. In the presence of lacerations or acute injuries, nerve dysfunction should be evaluated by assessment of 2-point discrimination and documentation of same. Patients may not appreciate lack of sensation until later; it is important to document sensory disturbance prior to initial treatment. Too often “sensation intact” means the examiner did not perform a detailed examination.

- Qualities. As in C.2, specificity is important. In addition, record frequency and inciting factors (e.g., the numbness occurs when I am driving for 20 minutes or more).

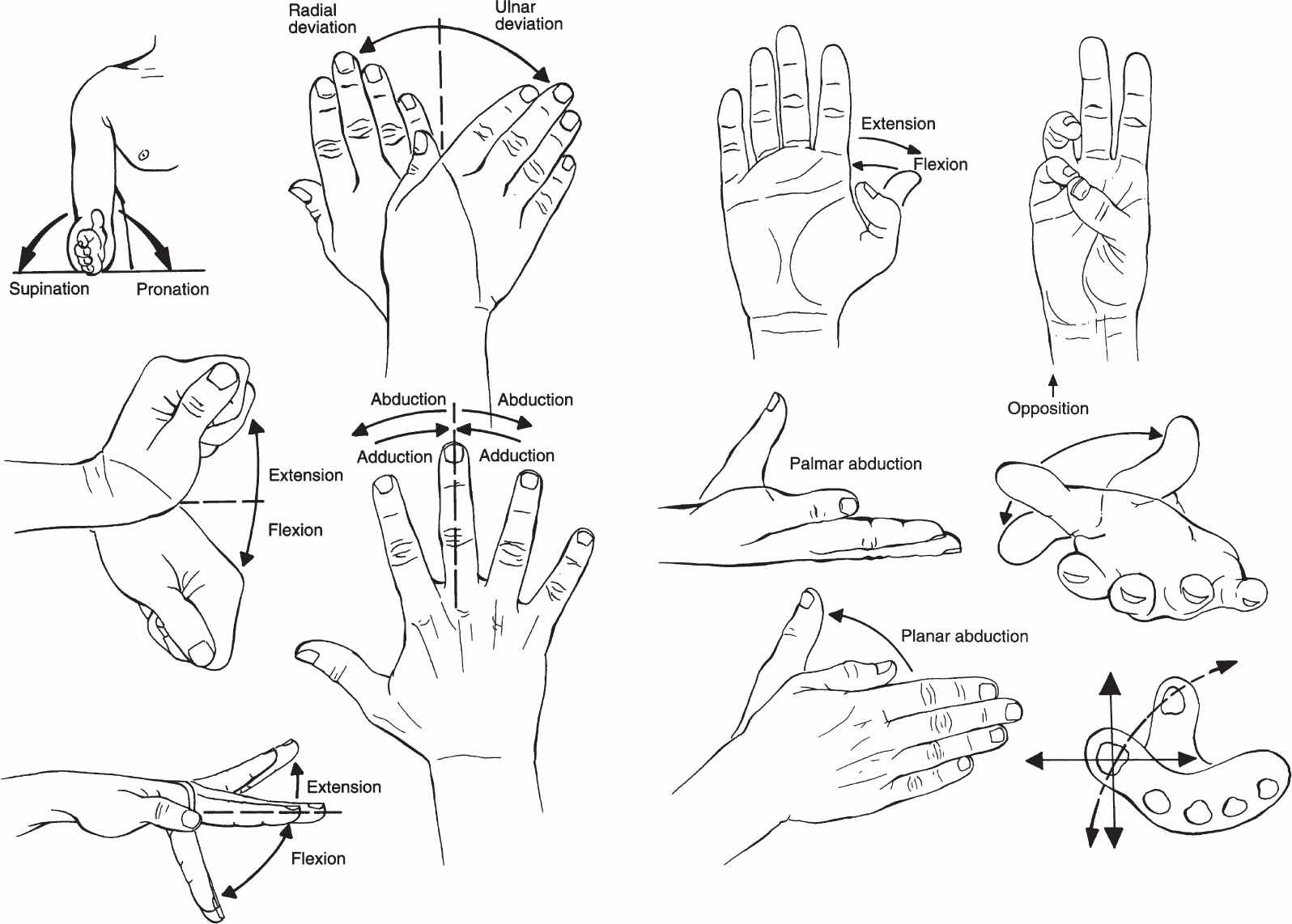

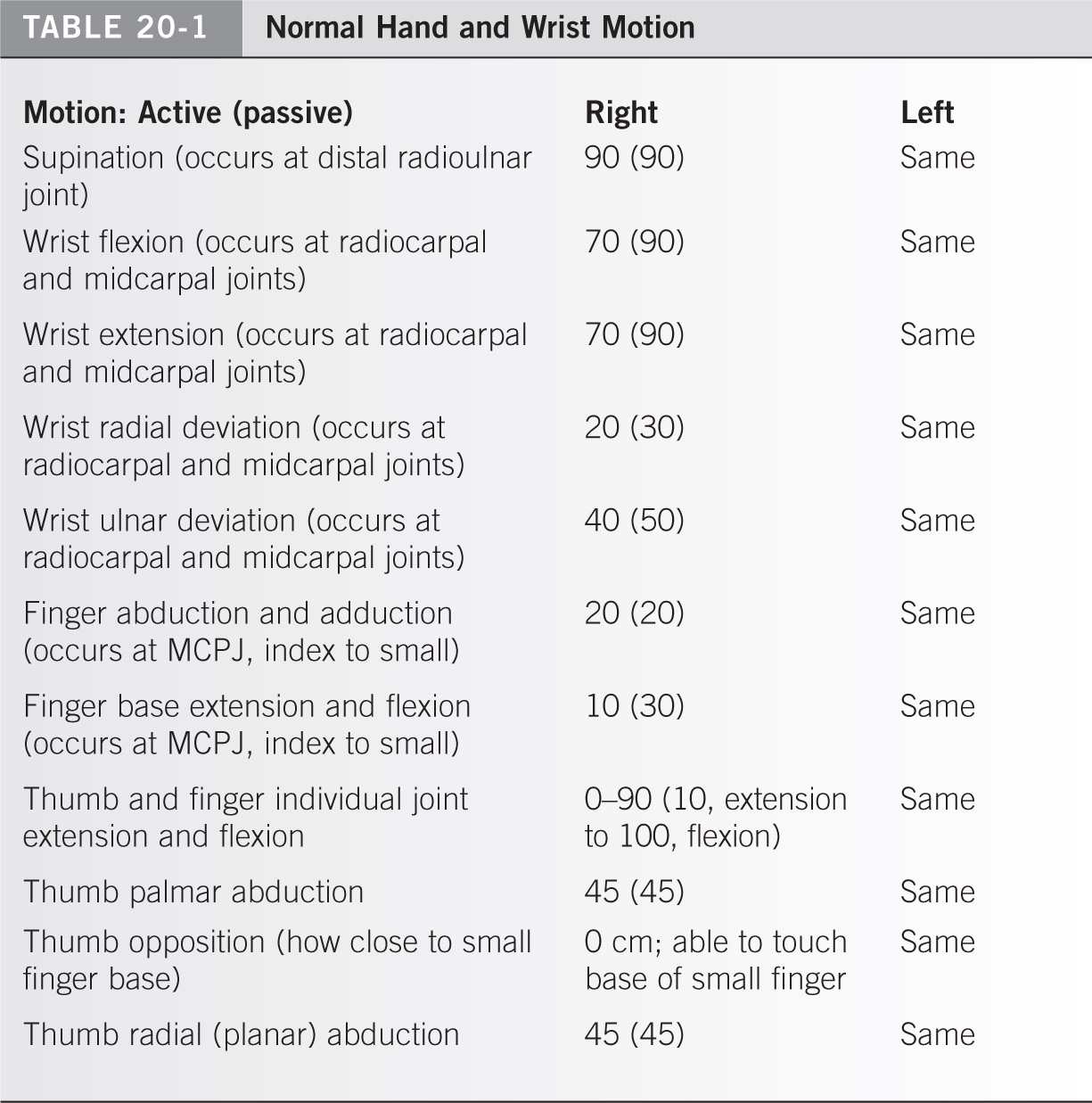

E. Range of motion. Specific ranges to be recorded are demonstrated in Fig. 20-1 and summarized in Table 20-1.

Figure 20-1. Terminology for describing forearm, hand, and digital motion. (From Seiler JG III. Essentials of Hand Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002, with permission.)

Idealized numbers are inserted. The key to a successful examination is to measure both sides in the affected areas.

- Active. Active motion helps to document the integrity of tendons and the stability/congruity of joints.

- Passive. Differences and similarities between active and passive motions can help to document/differentiate several conditions, for example, disrupted tendons (active will be low/absent and passive will be high/normal) and stiff joints (active will be low and passive will be low).

F. Strength. Generally, the international classification for muscle strength is used. Thus, a muscle can be graded from 0 (flaccid and no evidence of innervation) to 5 (normal). However, specific strengths are often measured in the hand and forearm and compared over time.

- Pinch strength. Measured with a “pinch gauge” and recorded in pounds or kilograms.

a. Key. Thumb to side of index or middle finger (strong, used for rotation).

b. Chuck. Thumb to pulp of two fingers (strong and moderately precise).

c. Tip. Thumb to one finger pulp (weakest and most precise).

2. Grip strength. Measured with a “dynomometer” and recorded in pounds or kilograms.

a. Can be recorded in several setting diameters and useful to “quantify” malingering as well as recovery over time. Normal grip strength follows a bell-shaped curve due to use of intrinsics, both extrinsic and intrinsic motors, and finally extrinsic muscular function as the dynomometer setting is increased from lower to higher settings.

III. PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A. General

Beyond skin, the hand has three primary functions: sensation, movement, and cosmesis. Nerves, bones and joints, and tendons and muscles all play an important role in determining the outcome after injury and care.

B. Region specific examination

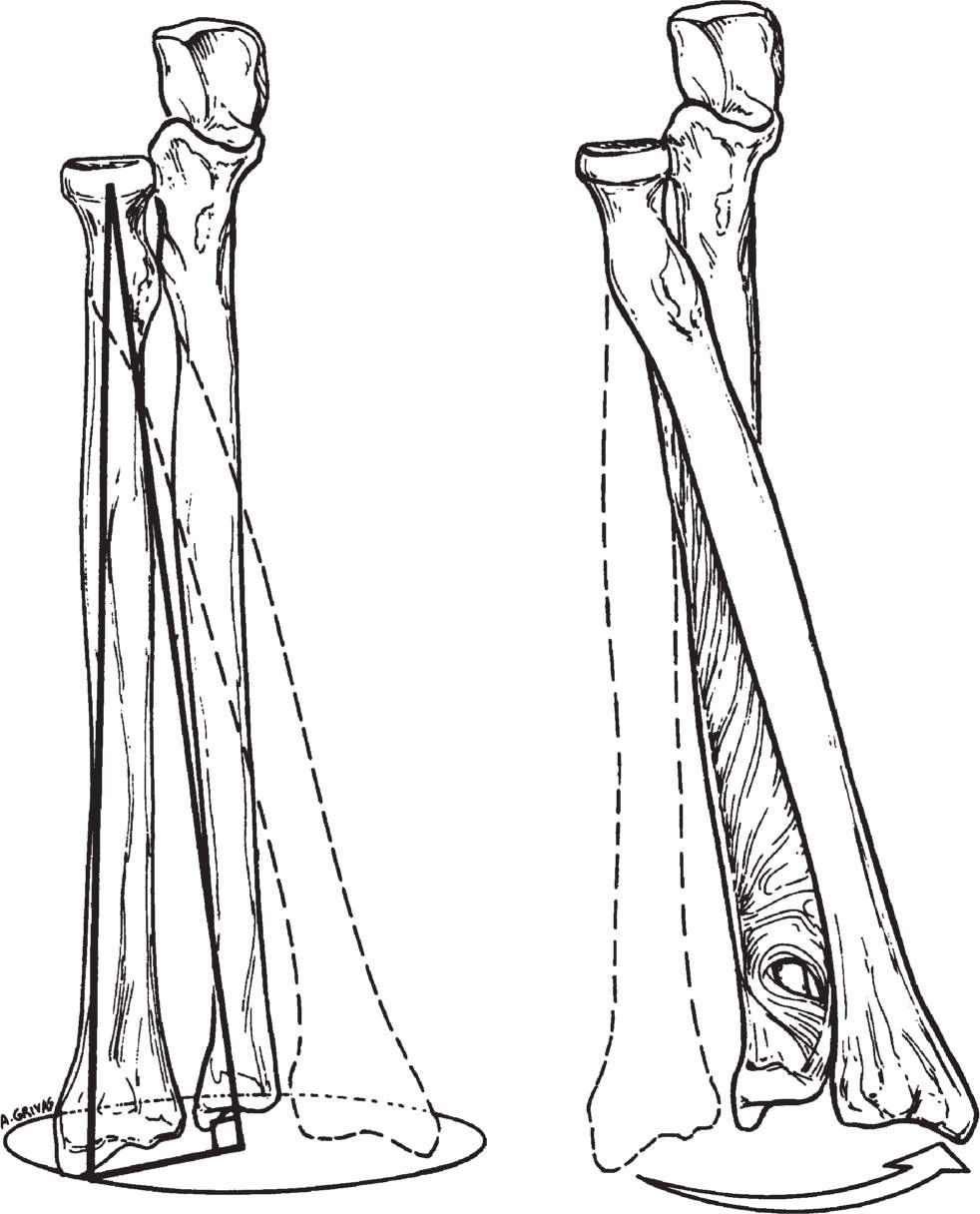

- Distal radioulnar joint. This joint works in combination with the proximal radioulnar joint to guide the rotation of the distal radius around the ulnar head (distal portion of the ulna). Fig. 20-2 demonstrates this important motion.

Figure 20-2. The axis of rotation of the radius with respect to the ulna, with the center of the axis of rotation being aligned beginning at the center of the radial head and ending near the center of the distal part of the ulna. Rotation is guided by the interosseous membrane and the triangular fibrocartilage. (From Peimer CA, ed. Surgery of the Hand and Upper Extremity. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1996, with permission.)

a. Muscle. The pronator quadratus muscle originates immediately proximal to the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ). It has a deep and superficial head and helps to stabilize and pronate the forearm. The muscle is innervated by the terminal branch of the anterior interosseous nerve. The muscle can be injured in conjunction with distal radius fractures.

b. Tendon. The extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) (sixth dorsal extensor compartment) and the extensor digiti minimi (fifth dorsal extensor compartement) tendons run alongside and dorsal to the ulnar head. Occasionally, the tendon sheath will tear, and the ECU tendon can become unstable. Also, a lax or irregular DRUJ can damage the extensor digit minimi tendons, such as in the setting of Vaughn Jackson ruptures with rheumatoid arthritis. Otherwise, no direct attachment of tendon to the joint occurs.

c. Joint/bone. The DRUJ is interesting. It is a “roll and slide” joint. Considerable variance in design occurs. What is universally true is that an unstable DRUJ is uncomfortable or painful. When the joint does not work well, it usually results in a loss of supination. An unusual but possible injury to the joint would be dislocation without fracture in either the volar or the dorsal direction. Twenty percent of the stability of this joint is conferred by the bony congruency.3

d. Triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC). First described in 1981, the TFCC is the major ligamentous stabilizer of the distal radioulnar joint and the ulnar-carpus joint.4

Within this triangular complex is cartilaginous material that may be injured either acutely (e.g., from a fall onto an outstretched hand) or chronically (e.g., from overuse with the wrist in an ulnar-deviated position such as with the use of a computer mouse). Patients with ulnar-sided wrist pain that is made worse with compression (analogous to hyperflexion of the knee when assessing for meniscal tears) may have a TFCC injury.

e. Nerve and vessel. A rare but reported injury is entrapment of the ulnar nerve and/or ulnar artery after reduction of a completely dislocated DRUJ. This would generally require a complete separation to occur between the radius and the ulnar head, but could also occur in a young child who could fracture through the physeal plate and in combination with a fracture just proximal to the ulnar head. In any event, the important point is to carefully assess nerve function before and after reduction maneuvers and carefully account for any change in function after reduction.

2. Wrist

a. Muscle. Indirectly and directly, muscles arise from the wrist. Specifically, the thenar and hypothenar muscles arise from the transverse carpal ligament (thenars) or the hook of hamate and the pisiform (hypothenars). Function of these muscles can be reduced in combination with injuries to their attachments. This would include an indirect injury to the attachments of the transverse carpal ligament such as would occur with a trapezial fracture, scaphoid tubercle fracture, or pisiform fracture.

b. Tendon. Tendons do not attach directly to any of the main seven carpal bones (the pisiform is a sesamoid and not a true carpal bone; the flexor carpi-ulnaris does surround the pisiform). However, the flexor carpi-radialis does appear to attach indirectly by way of a sheath to the scaphoid tubercle and consequently transfer a flexion vector to the scaphoid. Also, the wrist and its adjacent soft tissues act as a guide for both the flexor and the extensor tendons. Specifically, the carpal canal guides the thumb and finger flexors as well as the median nerve. The extensor retinaculum (Fig. 20-3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree