Chapter 1 Acute Paediatrics

Neuromuscular disorders

The most common neuromuscular disorders

• The largest group of neuromuscular disorders is the progressive muscular dystrophies: Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD, a milder form of DMD) and a group of childhood limb girdle dystrophies. The main features of these disorders are that ambulation is achieved in childhood but a large proportion of children will lose it before adulthood.

• Congenital muscular dystrophies (CMD): a wide spectrum of disorders characterised by weakness and severe and progressive contractures, which are a major cause of functional limitation. Depending on severity of the disorder, children may or may never walk, and those who walk may lose ambulation.

• The congenital myopathies: another diverse group of conditions, while there can be quite severe respiratory involvement in some types, they are much more slowly progressive than the dystrophies. Walking ability is variable as above.

• Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a neurogenic disorder; a problem of the nerve impulses not reaching muscles. It is not considered progressive in childhood, but growth greatly affects function and development of scoliosis in non-ambulant children. Children with SMA are grouped into those with severe SMA (type 1) who never achieve independent sitting; moderate or type 2 SMA, who achieve independent sitting but not independent walking; type 3, mild SMA, who do walk, but may lose the ability before adulthood.

• Peripheral neuropathies: including the largest group, Charcot–Marie–Tooth syndrome, are slowly progressive disorders primarily affecting nerves and nerve sheaths and can interfere with lower arm and hand and lower leg and foot function. Almost all will walk into adulthood but need foot orthotics and possibly foot surgery. Foot pain is common. They tend to have weak hands and fatigue with writing.

• Arthrogryposis is the term used to describe children born with joint contractures. There are several causes, some with underlying neurogenic or neuromuscular origins. In some forms of CMD babies are born with contractures.

• Congenital myotonic dystrophy (DM1) is a relatively common disorder characterised by mild weakness, developmental delay, fatigue, and learning difficulties. The children have frequent incidence of talipes. The children should achieve ambulation.

Priorities of physiotherapy management

Improve or maintain power

• In the muscular dystrophies, increased muscle damage can be caused by using weights or repeated eccentric muscle work.

• Open chain exercise cannot be easily achieved by non-ambulant children.

• Asymmetry of power is extremely common; it is important to ensure exercise is tailored to produce symmetrical work.

• Muscle imbalance can be increased, with resultant increase in contractures if the exercise programmes do not target the correct muscle groups.

The weakest muscles

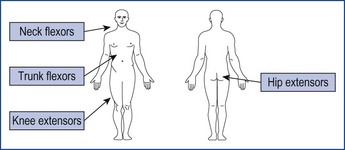

In many disorders the knee extensors, hip extensors and neck and trunk flexors are weak (Figure 1.1).

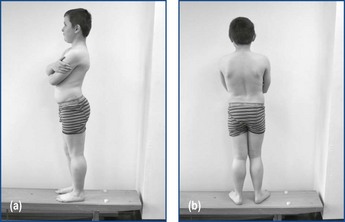

The knee and hip extensors weakness causes the hyper-lordotic posture seen in DMD and other conditions (Figure 1.2a, b).

Exercise and exercise programmes

Trampolining, scooters, gymnastics, rugby and weights (in most cases) are not advised.

Prevent or reduce contractures

The management of contractures can be effected in the following ways.

Splinting

Night time Ankle Foot Orthoses (AFO) to maintain ankle range have been shown, when used with stretching, to be most effective at maintaining range. They also help to prevent long-term foot deformities in non-ambulant children (Figure 1.3).

Serial casting

1. Serial casting should never last more than 15 days.

2. Casting should never be painful.

3. The first cast is a resting splint, and will be the most effective.

4. When casting ankles in an ambulant child, both ankles must be cast, irrespective of whether both ankles are tight.

5. Ambulant children should always be able to walk in the casts.

6. Removable splints will need to be considered for elbows and knees if the casting interferes with function, sleep or mobility.

Encourage and maintain mobility

The use of orthoses is common in neuromuscular disorders to achieve or maintain ambulation.

Prevent or reduce pain

Revision

The aims of physiotherapy in these children are:

1. To maintain maximum useful function – including respiratory function.

2. Ensure no physiotherapy is painful.

3. Physiotherapy should be targeted and specific – it should be made to fit with daily routine, must be fun and seen to be beneficial.

4. It must not increase the burden of care.

5. Ensure that any care is done in the context of the family.

Musculoskeletal

• Most young children are unlikely to co-operate with a formalised exercise programme so the creative use of toys and play is needed to encourage the child to move and maintain their interest.

• The physiotherapist should spend more time teaching parents, carers and teaching assistants how to handle and position their child so that they can continue therapy outside the physiotherapy sessions.

• Support, reassurance, gaining consent to carry out treatment and dealing sensitively with often highly anxious parents all play a central role in paediatric physiotherapy.

• Being aware of wider influences such as religious beliefs, past experiences, as well as individual coping abilities is all part of successfully managing the child and their family.

• Young skeletons have the potential to heal and remodel rapidly, but muscle imbalance, injury to growth plate through trauma or infections (e.g. meningococcal septicaemia), and certain conditions (e.g. Blount’s disease) may lead to asymmetrical growth and progressive deformity as the child grows.

• The treatment of common conditions, such as developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) and congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV), combines this remodeling ability of the growing skeleton with an understanding of the laws governing the remodeling of bone, which state that by improving the biomechanical environment, abnormal growth patterns may be reversed–Heuter–Volkmann law (Rauch 2005).

Normal variants

• If the presenting problem is symmetrical, symptom-free, without stiffness or systemic involvement and there is no skeletal dysplasia (refer to 5 ‘S’s’ in assessment volume), it is probably a normal variant and requires no intervention.

• The most common causes of concern are in toeing, bowlegs (genu varus), knock-knees (genu valgus) and flat foot (planovalgus).

• The role of the physiotherapist in these conditions is to rule out anything more sinister and then monitor the child’s development and functional abilities whilst reassuring the parents that they are likely to resolve as the child grows.

Abnormalities of the hip

Developmental dysplasia of the hip

• This term describes the spectrum of hip instability ranging from a shallow (dysplastic) acetabulum to the irreducibly dislocated hip.

• In the infant DDH may present as instability, in a toddler as a limp, and in an adolescent as exercise-induced pain.

• Conservative treatment is likely to be successful only if the diagnosis is made early.

• However, normal hips may be unstable at birth because of ligamentous laxity and stabilise within the first couple of weeks of life so require no treatment.

• The principles of treatment are the same at any age and, put simply are: ‘Get it down, Get it in, Keep it in, Monitor’.

• Hips that remain unstable or are dislocated are treated with harnesses or splints which aim to hold the hip in its reduced position of abduction and flexion.

• The most commonly used splint is the Pavlik harness, which allows controlled movement.

• Often it is the role of the physiotherapist to apply the splint and, essentially, to monitor the baby closely whilst in the harness.

• The harness will need frequent adjustment as the child grows to reduce the risk of avascular necrosis and the parents will need to be advised to ensure their baby keeps kicking as failure to do so may indicate femoral nerve palsy.

• In infants over the age of 4–6 months, closed reduction is usually required and the hip held in a hip spica cast for some months.

• The older the child becomes, the less likely it is that reduction by closed methods will succeed and open reduction, together with bony realignment and hip spica application, is necessary.

• Open reduction becomes more difficult and less successful in the older child and so surgery is often not undertaken over the age of 6–8 years in bilateral cases and over 8–10 years in unilateral.

• Physiotherapy involvement in these children will include advising the parents on manual handling and positioning the child in the spica and providing information on suitable buggies/chairs/car seats.

• On spica removal, physiotherapy will be targeted at regaining range of movement and muscle strength and, depending on the age of the child, re-education of gait.

• Passive movement of the knee should be avoided due to the risk of supracondylar fracture but the child should be encouraged to move as normally as possible.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree