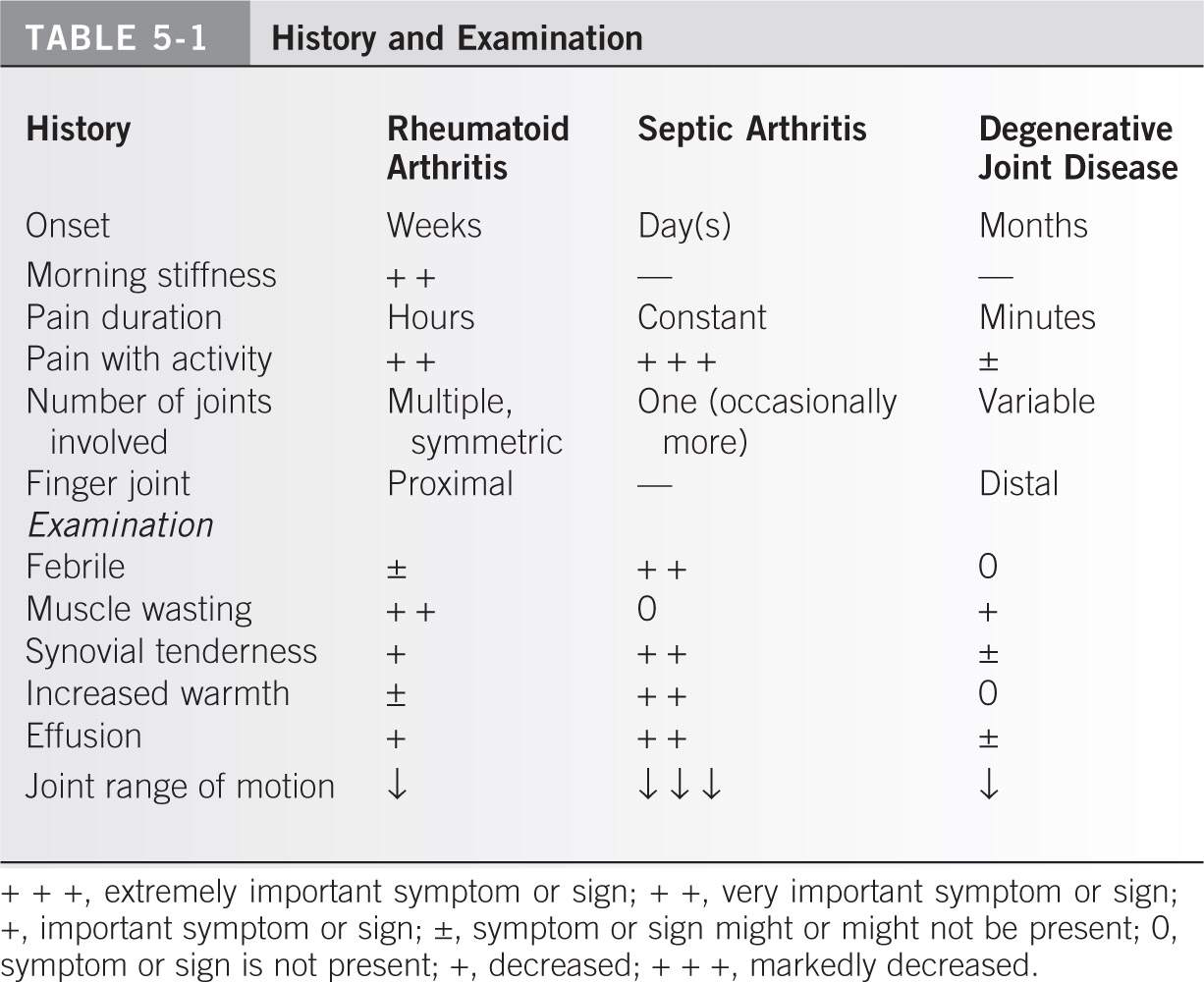

I. HISTORY. Document the onset of the symptoms: Did the joint pain begin days, weeks, or months ago? Morning stiffness is important to differentiate inflammatory forms of arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis [RA] and ankylosing spondylitis) from noninflammatory forms (degenerative joint disease). The character and duration of the pain are more important. Is the pain only associated with activity or is it present even at rest? Is only one joint involved or are multiple joints affected? Are they symmetrically involved? In the hands, the proximal finger joints are often involved with RA and the distal finger joints are more often involved in osteoarthritis1 (Table 5-1). A thorough history of medical problems and social issues and a current review of systems are essential. One must consider possible exposure to infectious diseases and current systemic symptoms of illness when differentiating the possibilities.

II. EXAMINATION. Check for fever because the temperature may be elevated with septic arthritis. Muscle wasting occurs more often with RA. Tenderness about the joint and increased warmth is more indicative of inflammatory conditions. The examination should determine the presence of an effusion (fluid in the joint). Severe guarding against joint motion associated with pain is usually indicative of a septic condition (Table 5-1).

III. ROENTGENOGRAPHIC AND LABORATORY DATA

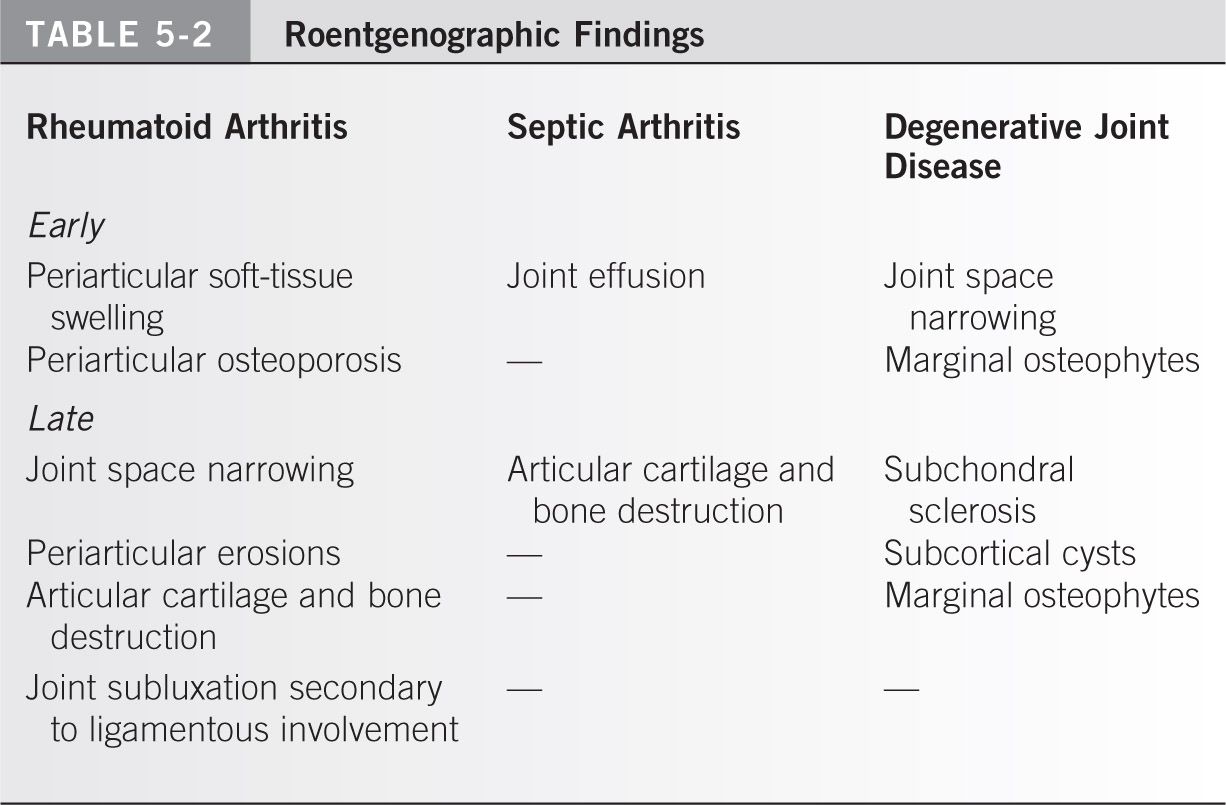

A. Roentgenographic findings. Look for evidence of periarticular soft-tissue swelling, joint effusion, osteopenia, joint space narrowing, periarticular erosions, joint subluxation, and articular cartilage or bone destruction.1 All of these findings are evidence of inflammatory (rheumatoid or septic) arthritis. In contrast, marginal osteophytes, subchondral cysts, joint space narrowing, and subchondral sclerosis are associated with osteoarthritis (Table 5-2). In the lower extremity, weight-bearing radiographs show joint space narrowing best, increasing the diagnostic value of the study.

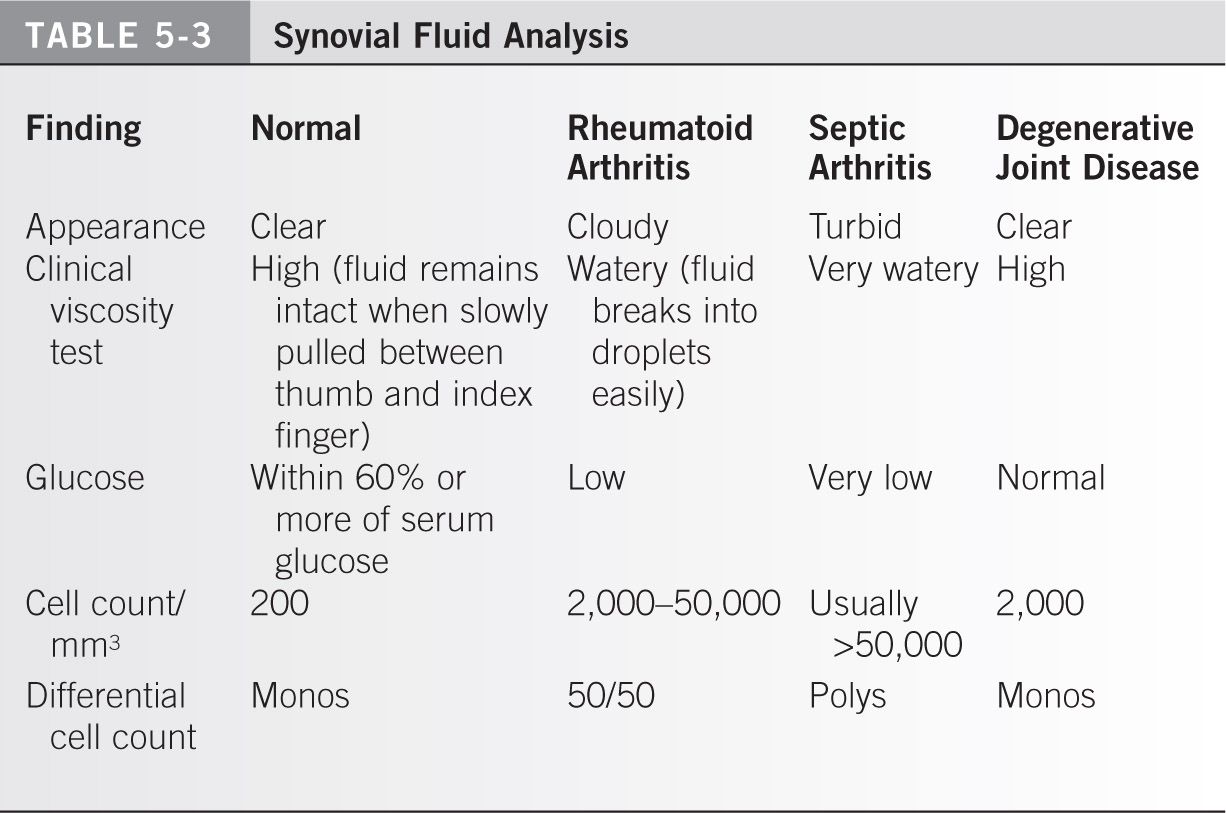

B. Laboratory data (Table 5-3)

- Synovial fluid analysis involves assessing the following:

a. Appearance (color)

b. Clot (presence or absence)

c. Viscosity

d. Glucose (compare with simultaneous serum glucose)

e. Cell count per cubic millimeter

g. The type of crystals that might be present in the joint fluid aspirate as evaluated under a polarizing light microscope

h. Gram stain and synovial fluid culture: aerobic, fungal, acid fast bacillus

2. Helpful blood tests include a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), uric acid, rheumatoid factor, and antinuclear antibody.

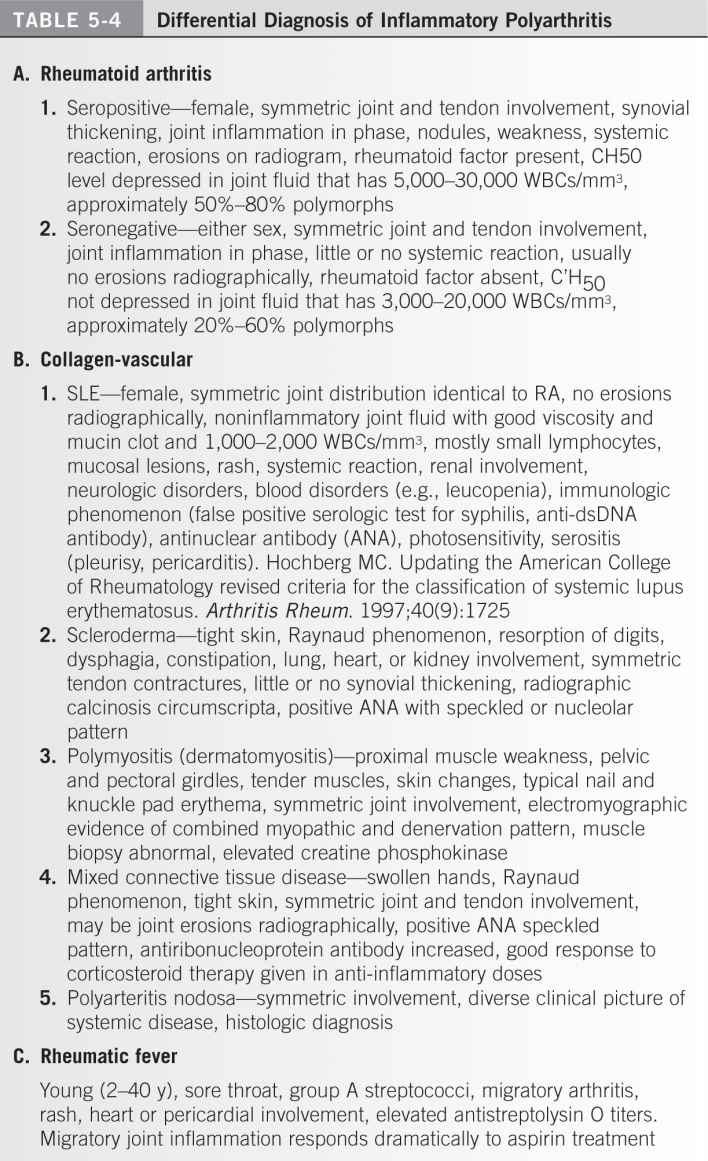

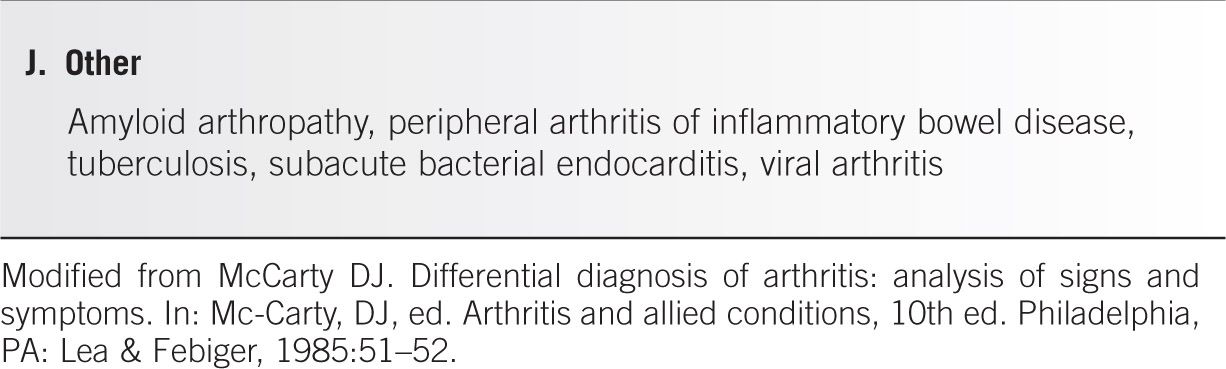

IV. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ACUTE NONTRAUMATIC JOINT CONDITIONS (Table 5-4)1–3

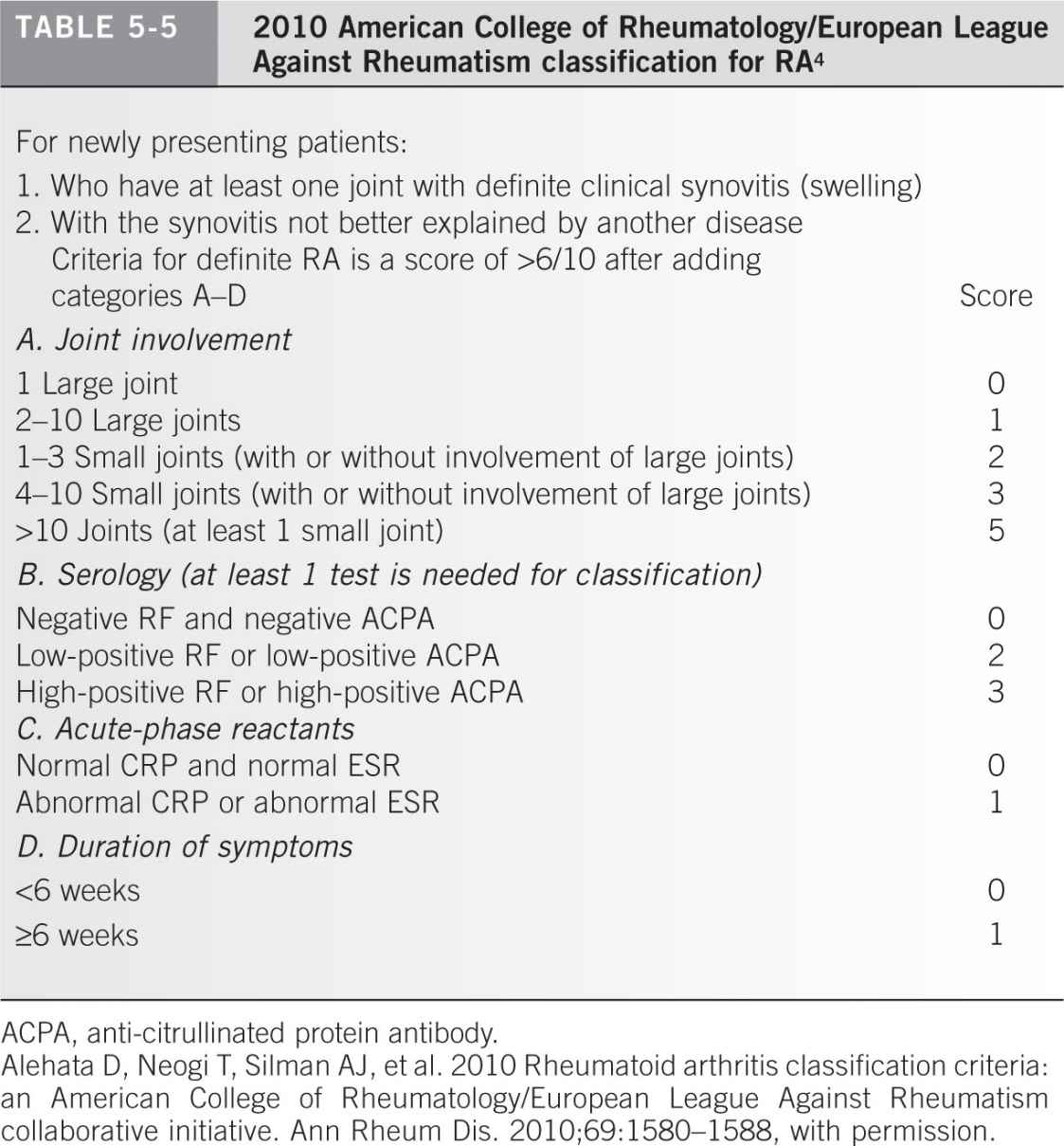

A. Rheumatoid arthritis (Table 5-5)4

- History reveals joint and tendon involvement that is more symmetric as the disease progresses. Females predominanate at 2.5 to 1.5

- Examination shows synovial thickening, joint tenderness, subcutaneous nodules, weakness associated with muscle wasting, and, often, systemic disease.

- Roentgenograms and laboratory data show that erosions are usually present, but rheumatoid factor is present in only 75% of patients. Roentgenograms are often normal in acute forms of RA except for signs of swelling or periarticular osteopenia. Joint fluid contains 2,000 to 50,000 WBCs per mm, approximately 40% to 80% of which are polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

B. Osteoarthritis (nonerosive degenerative joint disease)

- History reveals a middle-aged or elderly patient unless the condition follows trauma.

- Examination reveals that angulatory deformities and osteophytes are frequently present in the later stages of disease.

- Roentgenograms show narrowing of the cartilage space associated with marginal osteophytes. There is often subchondral bone sclerosis and occasionally subchondral cysts, which accompany these findings in the weight-bearing joints.

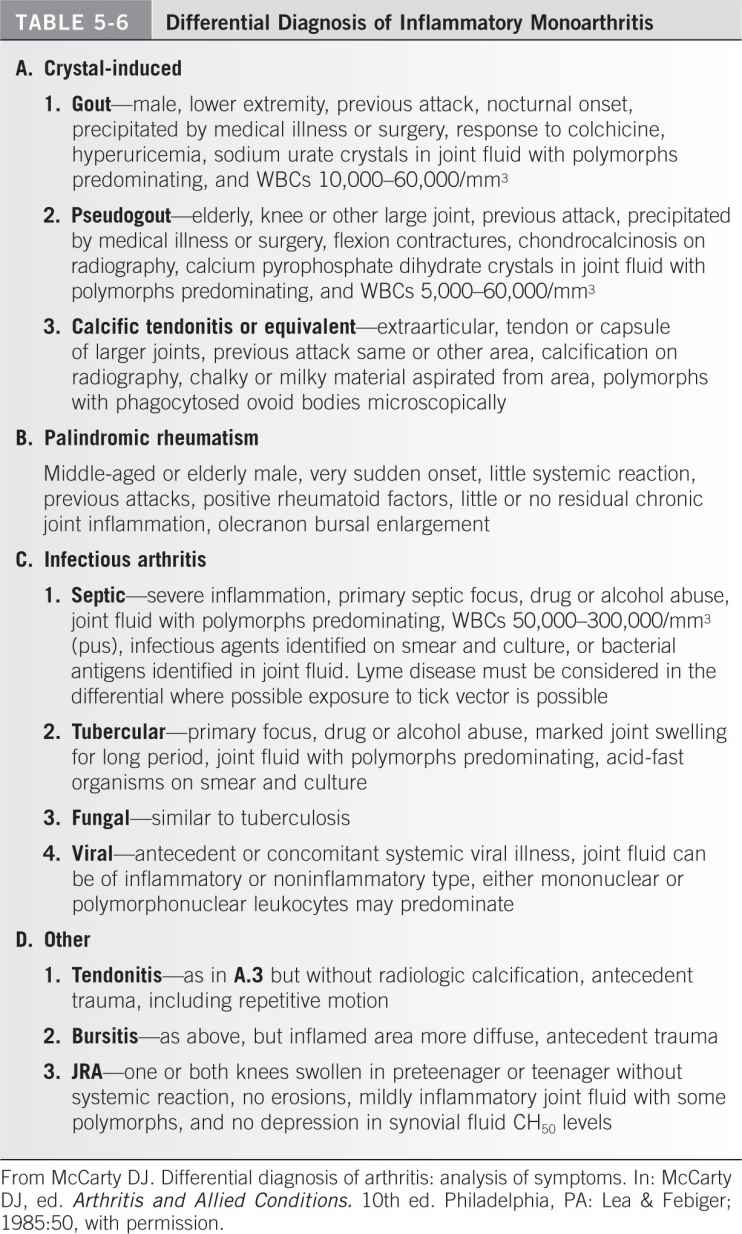

C. Crystal-induced arthritis (Table 5-6)

- Gouty arthritis

a. The patient may report a history of similar attacks.

b. Examination can show redness and warmth over the affected joint, typically the first metatarsal-phalangeal joint. Later, symmetric arthritis with contractures and tophi (subcutaneous crystal deposits) may develop.

c. Laboratory findings include hyperuricemia and synovial fluid containing monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. The crystals, which are seen by compensated polarized light microscopy (sometimes by ordinary light microscopy), are negatively birefringent, needle-shaped rods.

2. Pseudogout

a. History sometimes reveals previous acute attacks.

b. Examination discloses a symmetric arthritis with frequent contractures of the metacarpophalangeal, wrist, elbow, shoulder, hip, knee, and ankle joints. Roentgenograms may reveal the presence of calcium deposits in cartilage or, less often, in ligaments, meniscus, and joint capsules (chondrocalcinosis). The knee is the most common site. Chondrocalcinosis has been classically associated with pseudogout, but this condition is also seen with a high frequency in hyperparathyroidism, hemochromatosis, hemosiderosis, hypophosphatasia, hypomagnesemia, hypothyroidism, gout, neuropathic joints, and aging.5

c. Laboratory analysis of the synovial fluid reveals calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals that are regularly shaped and weakly positively birefringent but have a different extinction angle compared with that of urate crystals.

D. Inflammatory polyarthritis other than RA (Table 5-4)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

a. History most commonly reveals symmetric joint distribution identical to RA in a female patient. Hair loss and Raynaud symptoms (vasospasm of digital arteries) are common.

b. Examination may disclose rash (facial erythema), mucosal lesions, serositis, renal (hypertension and hematuria or edema), and brain (altered mental status, focal neurologic deficits) involvement. Joint involvement of the hands and wrists are most common followed by the knee.

c. Laboratory evaluation commonly shows anemia (40%), leukopenia (20%), and thrombocytopenia (30%). A depressed serum C3 and C4 and elevated antinuclear antibody (95% sensitive), anti-dsDNA antibody (70% sensitive) and anti-Sm antibody (30% sensitive, highly specific) are found. Antiphospholipid antibodies present in 50% of lupus cases. Test should also be done to check kidney function.6 Joint fluid is noninflammatory with normal viscosity* and mucin,† and 1,000 to 2,000 WBCs per mm, which are mostly lymphocytes.

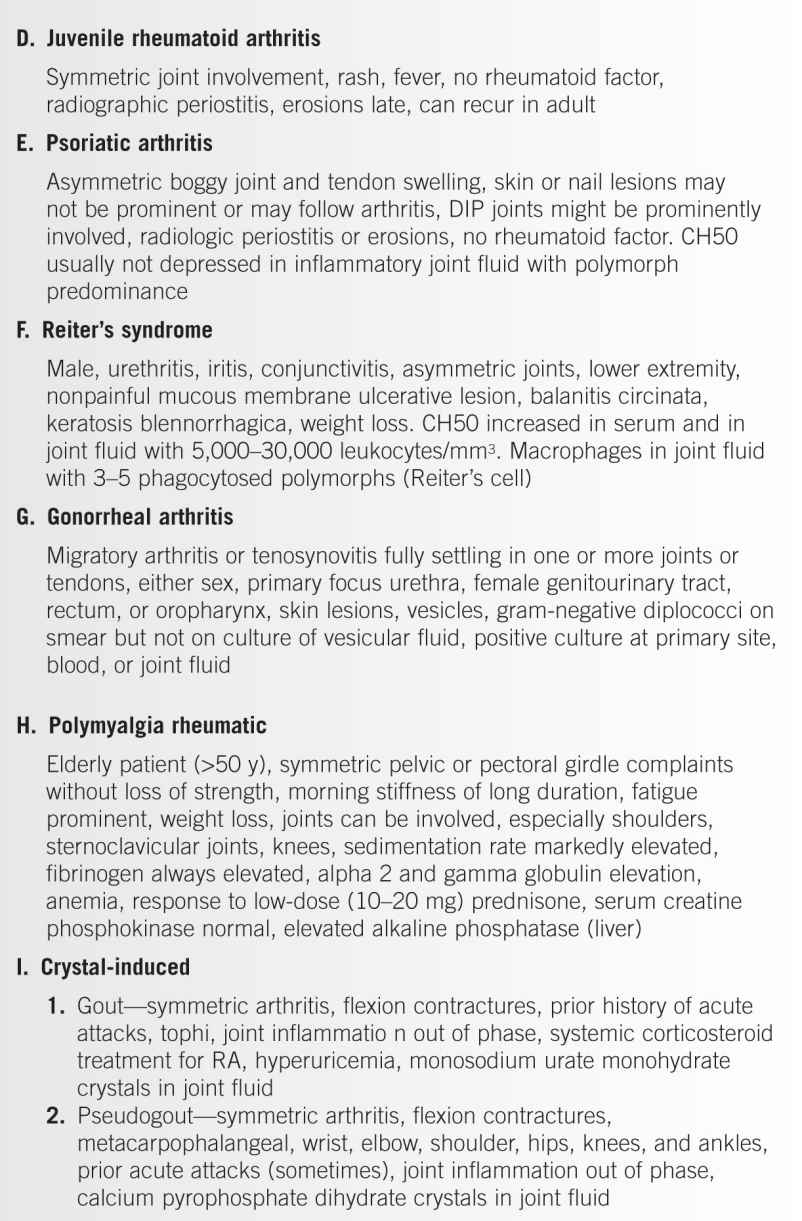

2. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA)

a. History shows symmetric joint involvement. The illness can recur in the adult. Short stature and limb length irregularity generally accompany the most severe forms because the physes are affected by the inflammatory process. Patients with systemic onset (10%) have intermittent fever of at least 3 days and a rash. Polyarticular onset (5 or more joints) comprises 40% of patients.7 There is a very high proportion of cervical spine involvement in the patients with JRA. The prevalence of JRA has been estimated to be between 57 and 113 per 100,000 children younger than 16 years in the United States.7

b. Examination may reveal a rash and fever. Cardiac, renal, and ocular abnormalities may be present. Eye involvement occurs in 30% to 50% of early onset JRA patients7 with anterior uveitis in 20% of those with pauciarticular disease (1 to 4 joints involved in the first 6 months).7

c. Laboratory tests show roentgenographic periostitis with erosions later in the course of disease. Rheumatoid factor or FANA may be present. Other causes of arthritis in the child or adolescent must be excluded.

E. Septic arthritis

- Bacterial

a. The history may indicate drug or alcohol abuse, systemic illness (e.g., diabetes, chronic renal failure, or poor nutrition).

b. Examination can reveal severe inflammation and often a primary septic focus. Severe splinting (autoprotection by muscle spasm) of the joint is present, and pain is associated with passive motion.

c. Laboratory tests show a purulent joint fluid with polymorphonuclear leukocytes predominating (WBCs: 50,000 to 300,000 per mm3). The infectious agent may be identified on smear or culture. Synovial glucose is less than 60% of a concurrent serum glucose. The ESR and CRP are elevated. Serial blood cultures obtained before antibiotic therapy often grow in the infecting organism.

2. Tubercular and fungal

a. History may reveal a focus, chronic immunodeficiency (HIV or AIDS), drug or alcohol abuse, or poor nutrition.

b. Examination shows marked chronic joint swelling.

c. Laboratory tests reveal predominating polymorphonuclear leukocytes with acid-fast organisms present on smear and culture.

a. History often indicates antecedent or concomitant systemic viral illness.

b. Laboratory analysis of joint fluid can mimic inflammatory or noninflammatory conditions. Either mononuclear or polymorphonuclear leukocytes can predominate.

F. Arthritis associated with infectious agents

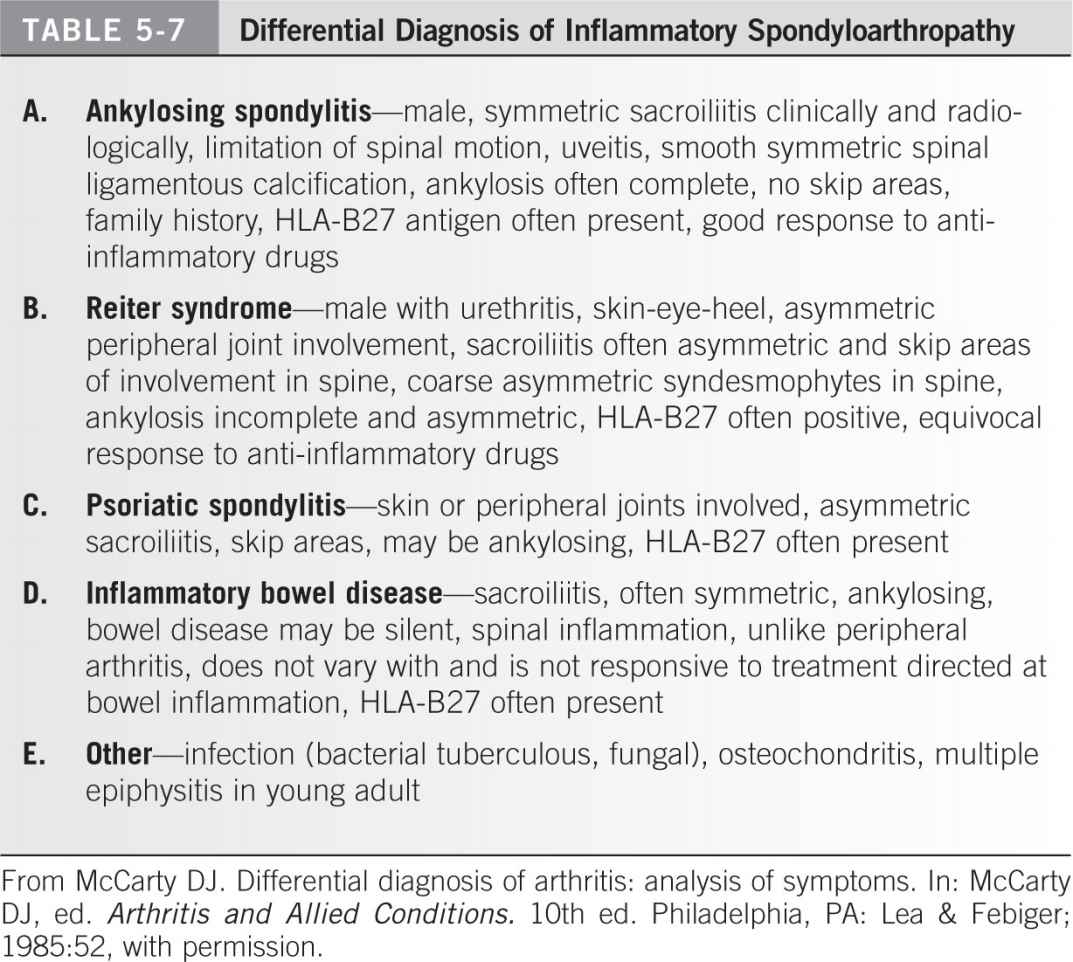

- Reiter syndrome

a. History often reveals a sexually active man (chlamydia is the most common organism identified) with urethritis and conjunctivitis accompanying the arthritis. Patients have an equivocal response to anti-inflammatory drugs.

b. Examination often reveals urethritis, iritis, conjunctivitis, and nonpainful mucous membrane ulcerative lesions, with asymmetric arthritis of the joints in the lower extremities or back. Roentgenograms may show an asymmetric sacroiliitis as well as isolated involvement of the spine (“skip” areas). Heel pain can be a common associated feature of the presentation.

c. Laboratory data. The joint fluid has 5,000 to 30,000 leukocytes per mm with macrophages that contain three to five phagocytosed polymorphonuclear leukocytes (so-called Reiter cell). Measurement of HLA-B27 antigen is not very useful.

2. Rheumatic fever

a. History reveals a sore throat, fever, rash, and migratory joint pain that responds dramatically to aspirin treatment in younger individuals (that are beyond the ages of Reye syndrome).

b. Examination shows a rash as well as heart (murmur) or pericardial (friction rub) involvement.

c. Laboratory tests result in group A streptococci isolated on throat cultures and an elevated antistreptolysin O titer.

3. HIV infection. Migratory arthralgia and myalgia with accompanying muscle weakness are features of this disease. Radiographic changes are nonspecific.

G. Inflammatory spondyloarthropathy (Table 5-7)

- Ankylosing spondylitis

a. History

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree