This is a challenging time for Sam’s rehabilitation practitioner. Sam has always needed a certain amount of motivating but it seems different this time. He really does seem depressed.

Depression is common among people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and may affect as many as 50% of people like Sam (Buckley et al., 2009). There is surprisingly little known about treatment of depression in the context of schizophrenia (Whitehead et al., 2003). While there was early optimism that atypical antipsychotics would reduce the prevalence of depression, there is little evidence that this has been the case and clinical trials have been inconclusive (Furtado & Srihari, 2008). While it is common practice to add antidepressant medication to the treatment regime when there is evidence of depression, it is unclear how effective this is (Whitehead et al., 2003).

In this chapter, we will show how Sam’s rehabilitation practitioner can use behavioural activation (Dimidjian et al., 2011) to help Sam overcome his depression. Behavioural activation (BA) is a simple structured treatment for depression that has a good track record for effectiveness in the treatment of major depression (Sturmey, 2009; Cuijpers et al., 2007). BA is well suited to treatment of people with impaired cognition because, unlike most psychotherapies, it does not rely on a person being able to use reasoning to overcome depression. While there has been limited research into the effectiveness of BA with people who have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, a small open trial with this population in the UK (Mairs et al., 2011) found that it was well received and was very effective in reducing both depression and negative symptoms.

Behavioural activation is also conceptually and practically uncomplicated for the practitioner. It is likely that for some practitioners, the programme outlined in this chapter will seem like a more thorough and systematic version of interventions they already use with depressed clients. A detailed manual (Lejuez et al., 2011) is readily available and the programme in this chapter is partly based on the manual, partly on modifications recommended by Mairs et al. (2011) and partly on the experience of the authors using BA and related interventions in rehabilitation practice with people like Sam.

There are some differences between using BA in schizophrenia and using it with someone who has an uncomplicated depression. Readers who are already familiar with BA will notice that we suggest the introduction of some enjoyable activities and tasks before values and goals are considered. Small changes in activity, with associated improvements in mood, will help to show the client how worthwhile the lifestyle changes can be. However, the standard linkage to values and goals then allows for more long-term, sustained changes to occur.

While the changes to Sam at the moment do look different from how he was in the past, it may not just be the depression that is reducing activity.

- Check his medication. Antipsychotic medication should be at the minimum effective dose to avoid excessive sedation. Has the medication changed recently? Heavy doses will make it harder for Sam to become more active.

- The schizophrenia may also be reducing motivation to engage in activities, and the degree to which this occurs can change over time. Even simple activities (e.g. going for a 10-minute walk each day) can be difficult. In each session, you may need to help Sam review the benefits of making an effort, and the degree of change may often need to be gradual, to maximise the chance of completion. If some activities can be with a friend or relative, that may increase the chance that they occur.

Cognitive difficulties can make it more difficult for people like Sam to remember to do the activity, and why. We have made changes to standard instructions for BA in the description below, to take account of these potential difficulties. Depending on the time available for sessions and the cognitive abilities of the person, one step may often need to be split or repeated over more than one session if the person is having difficulty concentrating. At regular points in each session, check that the client understands and can recall the content, e.g. ask them to summarise what you have both been discussing. If they show attentional or memory lapses, see if you can take a break for a few minutes or delay further work until your next contact. When you return to the discussion, give them a brief summary and check they understand, before moving on.

Introducing behavioural activation

While BA is simple, it will make demands on Sam and it is important he understands what he has to do and why you are asking him to do these things.

Sam may already know that he is feeling different from usual and is depressed. However, sometimes people just slip into depression and it feels as if it is their normal state. When this happens, it is important the person becomes aware that how he is feeling now is not how he usually feels. This can often be done by pointing to levels of activity and interest in the recent past. For example, ‘You always used to watch football on television but now you can’t be bothered’ or ‘You used to play your guitar most days but you haven’t done that for 2 months’. A family member, partner or friend can often help identify changes in interests or activities.

If Sam is depressed, give him some key messages about depression.

- Depression is common – many people (including people without prior mental health problems) experience feelings and difficulties just like those he has been experiencing.

- When people are depressed, they often stop doing things they enjoy. They also put off doing things they need to get done.

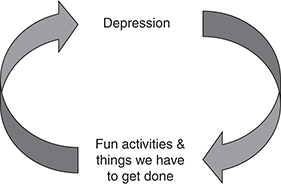

- Stopping fun things and putting off tasks makes people feel even worse, but starting to do them again can make them feel better. Show Sam Figure 8.1.

- Sam can actively help with recovering his usual mood, by becoming more active again.

Reviewing current activities and showing links with mood

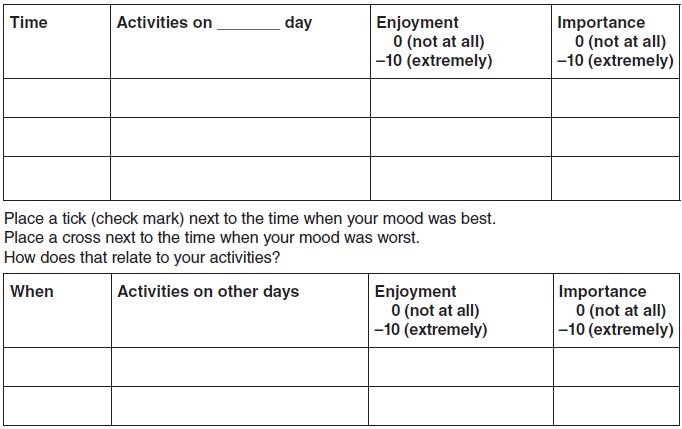

Using the form in Table 8.1, help the person recall their activities on the previous day. Try to do it hour by hour, except for periods of extended activity of the same kind, such as sleep, which can be logged in a block. Ask if that day was different from the rest of the week and pay particular attention to the previous weekend. Note down activities that only occur on some days, and get the client to rate them using the same procedure as below.

The monitoring form has four columns. The first records the hour (or hours), the second the activity (or activities) and the third and fourth columns ask Sam to rate the activities for enjoyment and importance. Ratings for enjoyment and importance use an 11-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely). Activities can be enjoyable but not important or vice versa. Some activities will have similar ratings for enjoyment and importance. Use the form to show that the person’s worst mood was when they were not enjoying themselves, and their better mood was when they achieved something or were doing something enjoyable.

Table 8.1 My activities.

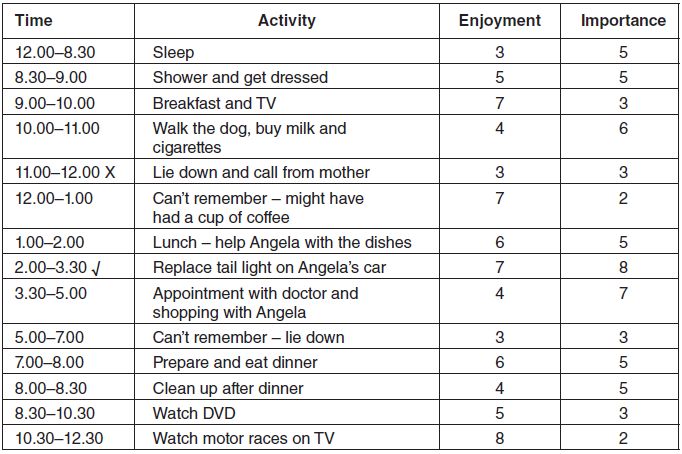

Table 8.2 sets out Sam’s initial rating with his practitioner as he did his best to reconstruct the previous day. Sam rated his sleep as not very enjoyable, because he was restless during the night and had some bad dreams. He rated it as reasonably important, because it is necessary but not helping him achieve anything. He rated the 30 minutes he spent showering and dressing as reasonably enjoyable. He quite likes standing in the shower but finding clothes and getting dressed are boring. He thought that, like sleep, it is just one of those things you have to do so it got a rating of 5 for importance. He spent an hour having breakfast and watching morning TV. He enjoyed his breakfast, which Angela made for him. He usually really enjoys food. Lately he has lost a bit of interest but it was still better than most things he did during the day. He always watches morning TV but does not pay much attention to what is on unless something really interesting has happened. He can’t remember what was on yesterday morning. He rated breakfast the same as sleep and showering but because it was combined with TV, which was not important at all, he gave an overall rating of 3.

After breakfast, Angela asked him to take her dog for a walk and pick up some milk and cigarettes while she cleaned up. The dog really likes a walk. When Sam is feeling good, he takes the dog for quite a long walk. At present, he feels he barely has the energy to get to the shop. He knows it is good for his health to walk so he rated the activity as a bit more important than the things he had done so far that day. However, he could not say he enjoyed it. He does not like going into the shop. The old man who runs it looks at him strangely. The only thing he enjoys is watching Angela’s dog sniffing about but even that irritates him at times. When he got home, he felt exhausted, even through the shop is only a few blocks away.

Table 8.2 Sam’s first activity record.

Sam doesn’t remember what happened when he got home, except that he had a lie-down for a while until the phone rang. It was his mother reminding him he had an appointment to see the doctor that afternoon. He talked briefly with her. She asked him how Angela was so he handed the phone over to Angela so she could tell her. They talked for a while and he lay down again. He does not like lying down during the day. It is very boring. He would not do it but he feels tired and can’t think of anything else to do. He rated this period as 3 for both enjoyment and importance. Sam was quite hazy about the next hour. He rated it 2 for importance: ‘can’t have been important or I would remember something’. He thinks he probably had a coffee during this period: ‘Angela always likes coffee in the middle of the day and asks me to make her one’. He quite enjoys drinking coffee and ‘I don’t mind making her one, because she does a lot for me’.

He thinks they had lunch between 1pm and 2pm. He remembers they had baked beans on toast because the beans stuck to the bottom of the saucepan when he was heating them. Angela asked him to stir them while she was making the toast but he forgot. She made a fuss about it but they weren’t badly burned and tasted fine. After lunch, Angela washed the dishes and he dried them. They soaked the saucepan so it would be easier to wash at dinner time. He rated this period as a 6 for enjoyment. The beans were nice but drying dishes is pretty boring. Lunch is another of those things you have to do so it rated 5 for importance.

After lunch he replaced the tail light on Angela’s car. The left-side brake light has not been working for a while and she was pulled over by the police the other day and told to fix it or the car would be certified unroadworthy. It took a while. The car is old and some of the screws were rusty. It was just a bulb that needed replacing but it took a while to find the right size. He likes working on cars. Even though it was an easy job, working out the best way to go about it, locating the right tools and sourcing the replacement part kept his mind occupied and for a while he forgot how he was feeling. He rated it as a 7 for enjoyment, ‘it was the highlight of my day really’, and 8 for importance, because having a defective brake light affects the safety of the vehicle and Angela has enough difficulty paying for fuel without having the cost of getting it recertified for roadworthiness.

Sam and Angela went out after fixing the car. While he saw the doctor, she went shopping. He had to wait half an hour to see the doctor and then it was in and out in 5–10 minutes. The doctor just asked a few questions about his depression and checked on whether he was experiencing side-effects from the medication. The doctor agreed that Sam was not showing much improvement but suggested they maintain the same medication and dose for another 3 weeks. He then met up with Angela and trailed around with her while she looked at clothes. He suggested to Angela that they have a coffee but she was concerned about money and said they could have coffee when they got home. All in all, the outing was very boring and he rated it as 4 for enjoyment. The only part of it he enjoyed was browsing through some car magazines in the doctor’s waiting room. He rated the importance of the appointment at 7 because ‘I guess they are trying to do something about my depression’.

Sam could not remember what happened in the next 2 hours. After he got home, he thinks he must have gone into the bedroom and laid down for a while. He does not recollect whether they had coffee when they got back but they might have. He rated this period the same as his morning lie-down. He remembers Angela coming into the bedroom around 7pm and asking him to help her cut up some vegetables. They had a bit of an argument when he suggested ordering in a pizza instead. Angela made soup with the vegetables and some lentils. It tasted good and was probably healthier than pizza. Cutting up vegetables was boring but easy enough. He rated the preparation and eating of dinner as 6 for enjoyment and 5 for importance. After dinner they cleaned up. Angela made him scrub the saucepan with the burnt beans that had been soaking all afternoon. That was easy enough. He rated the enjoyment of cleaning up as 4 and the importance as 5.

The rest of the night was spent watching television. Angela had rented a movie while they were out. It was OK but a ‘chick-flic’. It was nice sitting on the couch with Angela with her snuggling up next to him. He rated the enjoyment as 7 and the importance as 6. It was nice doing something together and not arguing. He knows it was important to do some things she liked even if he was not very interested. After the DVD, Angela said she was feeling tired and went to bed. Sam decided to stay up and watch the motor races, which were on one of the cable channels. He likes motor races: ‘you never know what will happen’. It was even more enjoyable than fixing Angela’s car but not at all important: ‘just killing time really’.

Sam went to bed around 12.30 but took a while to get to sleep. He does not remember how long. He woke up during the night and made himself a cup of tea but does not remember when or how long he was awake for.

When Sam thought about the time he felt worse, it was when he was lying down in the morning and was thinking about how boring his life was. He felt best when he fixed the tail light. The rehabilitation practitioner showed him Figure 8.1 again, and showed how his experience fitted the picture. Maybe if he could do more things that made him feel good, his depression might lift. Sam agreed but said it would be hard to get moving. His practitioner said they could go slowly to help him get moving. First, it may be a good idea to get a better picture of how things are now, so they could see when things get better. Also, they needed to look at what he’d like to do.

Some clients like Sam will be able to monitor their activities between sessions; if so, talk about why it will be important to keep track of what they have been doing, so they can see how it changes. Negotiate a time to fill in the daily monitoring record, e.g. 10 minutes at the end of the day might work. Get the client to set up some reminders – phones are perfect for this. Some clients prefer paper copies and others will work better with an electronic form. You might even be able to set up a personalised online form.

However, many if not most people with schizophrenia find this task difficult to remember, or find it hard to motivate themselves to do it. In those cases, use the next session to do another review of the previous day or two, or phone them during the next week to do a brief review of the previous day.

Review of activities

The next session should take place as soon as possible, but no later than a week after the previous session. If feasible, a follow-up session 3 days after the previous one is preferable.

If the client has been self-monitoring and comes with forms that are more or less fully completed, you have a great start to BA. However, don’t be surprised if there are missing and/or incomplete forms. Depression affects both memory and motivation. When the depression is coupled with a condition such as schizophrenia, the obstacles are even greater. Try reconstructing the previous day, and ideally a day on the previous weekend, and look for days when the person undertook other activities. If you and Sam decide to keep trying self-monitoring, consider enlisting the support of a partner or family member, using different kinds of reminders or making small changes to the forms. Check motivation and use motivational strategies if the client is ambivalent. Be empathic but clear: ‘I know these forms can be boring but it’s essential that we discover some ways to help you feel better’.

If the client has not been self-monitoring, see if they can remember what they did the previous day, and (if possible) a day on the previous weekend. Ask if there were any days when they did other things; write those down or fill out a third form.

Review the patterns. How similar are the days? Are there certain times when more enjoyable or more important activities are likely to occur? When are the flat periods when nothing that is either enjoyable or important takes place? Review the best and worst mood on the previous day, and again relate moods to enjoyment and achievement.

Explore opportunities to increase the amount of enjoyable activity, the amount of important activity and the enjoyment of important activity. Use a brief checklist of activities like those in Figure 8.1 to identify ones the client would like to do more often (or start doing again). Use your knowledge of the client to help them add any other activities that are relevant to them.

If the client does not identify any tasks they want to get done, leave that for the moment and focus on things they may enjoy (Box 8.1). If they say they would not enjoy any activities, get them to identify ones they used to enjoy. Tell them that when they feel down, things may not be as much fun as usual but they may still help to lift their mood.