Actinomycosis

Jeffrey R. Starke

Actinomycosis, a rare infection in children, is marked by chronic granulomatous or suppurative inflammation and formation of external sinus tracts. Another hallmark of this infection is contiguous spread unimpeded by the usual anatomic tissue barriers. Metastatic spread to distant sites also occurs. Infection occurs when these endogenous oral commensal organisms invade tissues of the face and neck, thorax, or intestines. Actinomycosis occurs worldwide and usually is not an opportunistic infection. The organism can be isolated from the saliva, dental surfaces, gingiva, or tonsillar crypts of 30% to 50% of normal adults, if specimens are cultured properly, and may be part of the normal intestinal flora. Gender, race, season, and occupation are not important epidemiologic factors. The infection is reported in children less frequently than in adults, probably because the major predisposing factor for invasive infection is chronically poor oral hygiene. Children who are predisposed to aspiration may be at higher risk of developing thoracic actinomycosis.

Actinomycosis in humans was reported first in 1857. The organism Actinomyces bovis (literally, “ray fungus of the cow”) was seen first in 1877 in granules from cattle with lumpy jaw syndrome. In 1878, similar granules were seen in human autopsy material; by 1885, actinomycosis in humans had been characterized. For decades, the etiologic agents of actinomycosis in cattle and humans were thought to be the same, but in 1940 A. bovis and A. israelii were shown to be distinct species.

Before the 1940s, the term actinomycosis designated infection from any actinomycete. In 1943, Waksman and Henrici separated the pathogenic Actinomycetaceae using oxygen requirements and mycelial fragmentation. Microaerophilic and anaerobic actinomycetes were placed in the genus Actinomyces, and aerobic pathogens were assigned to the genus Nocardia. Current classification places the aerobic actinomycetes in a separate family, Nocardiaceae.

ETIOLOGIC AGENTS

Actinomycosis may be caused by any of several agents that have been placed in the genera Actinomyces and Arachnia. These organisms are gram-positive, facultative or strict anaerobes,

with a morphology that varies from diphtheroid to mycelial. Branching is a characteristic feature, but demonstrating it in clinical samples may be difficult. Members of both genera are oral commensals.

with a morphology that varies from diphtheroid to mycelial. Branching is a characteristic feature, but demonstrating it in clinical samples may be difficult. Members of both genera are oral commensals.

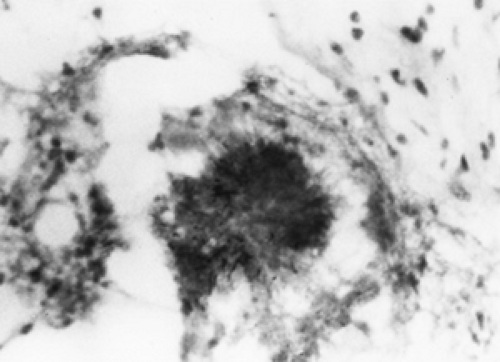

A characteristic of all organisms that cause actinomycosis is the propensity to form sulfur granules (Fig. 151.1). These granules are hard, gritty, and yellow or white, and average 2 mm in diameter. Usually, they are round basophilic masses with a fringe of eosinophilic clubs, and granules caused by other organisms (such as fungi, Nocardia, Streptomyces, and Staphylococcus) lack the characteristic clubbed fringe. Granules may be difficult to find, especially in chronic infections, and they may be in an abscess wall or sinus tract rather than in the pus or drainage. The granule represents a mycelian mass held together by calcium phosphate and, therefore, cannot form in vitro.

The most common agent of human actinomycosis is A. israelii. Grown on artificial media, the early colonies are branched filaments radiating from the center “spider” colony. Usually, the mature colonies are white, opaque, and rough. In enriched thioglycolate broth, discrete breadcrumb-like colonies form and, after 7 to 10 days of growth on solid media, they have a heaped and lobulated appearance, like the surface of a molar tooth.

Several other species of Actinomyces have been isolated from human cases of actinomycosis. A. naeslundii has been isolated from blood, thoracic abscess, cervicofacial infection, gallbladder, and pleural empyema. Granules are seen less commonly, and free mycelia are found more commonly than in infection caused by A. israelii. A. naeslundii and A. israelii have similar biochemical features, although growing A. naeslundii on artificial media may be slow or difficult.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree