Acromioclavicular Disorders

Harris S. Slone

Spero G. Karas

DEFINITION

A number of pathologic processes may affect the acromioclavicular (AC) joint, altering anatomy, biomechanics, and normal function.

The most common of these are primary osteoarthritis, posttraumatic arthritis, and distal clavicle osteolysis.

ANATOMY

The AC articulation is a diarthrodial joint composed of the medial end of the acromion and the distal end of the clavicle. The joint supports the shoulder girdle through the clavicular strut.

A fibrocartilaginous intra-articular disc is present in variable shape and size.

The average size of the AC joint is 9 × 19 mm.5 The sagittal orientation of the joint surface varies, ranging from an almost vertical orientation to a downsloping medial angulation of 50 degrees.5

The stability of the AC joint is provided by capsular (AC) ligaments, the extracapsular (coracoclavicular) ligaments, and the fascial attachments of the overlying deltoid and trapezius.

The AC ligaments are the primary restraint to anteroposterior translation.

The superior AC ligament, reinforced by attachments of the deltoid and trapezius fascia, resists vertical translation at small physiologic loads. However, the coracoclavicular ligaments are the primary restraint to superior displacement under large loads.

PATHOGENESIS

Degeneration of the AC joint is a natural part of aging.

DePalma5 has shown degeneration of the fibrocartilaginous disc as early as the second decade of life and degenerative changes in the AC joint commonly by the fourth decade.

The superficial location of the joint may predispose it to traumatic injury.

The clavicle acts as a supporting strut for the scapula, helping maintain its orientation and biomechanical advantage for glenohumeral motion. Large forces may be transmitted from the extremity to the axial skeleton through the small surface area (9 × 19 mm) of the AC joint.

Repetitive transmission of large forces, such as weightlifting or heavy labor, may result in degeneration of the joint.

Repetitive microtrauma to the AC joint may cause subchondral fatigue fractures that undergo a subsequent hypervascular response, resulting in reabsorption and osteolysis (distal clavicular osteolysis).

NATURAL HISTORY

Despite the frequency of radiographically evident AC joint degeneration, symptomatic arthritis of the AC joint is relatively uncommon.

Studies have shown that 8% to 42% of patients with types I and II AC joint separations develop chronic AC symptoms from posttraumatic arthritis.2,4

Distal clavicle fractures or previous AC joint separation may also result in posttraumatic arthritis.

Patients with symptomatic AC joint degeneration can be successfully treated nonoperatively with activity modification.13

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM FINDINGS

Patients with isolated AC pathology typically experience pain over the anterior or superior aspect of the shoulder in an area between the distal one-third of the clavicle and the deltoid insertion.

Pain occurs with activities of daily living that involve internal rotation and adduction such as putting on a coat sleeve, hooking a brassiere, or washing the opposite axilla.

Younger patients may complain of pain with weightlifting, golf swing follow-through, swimming, or throwing.

Physical examination of the AC joint includes the following:

Palpation: Tenderness on direct palpation suggests AC pathology.

Cross-arm adduction test: This test is highly sensitive but not specific for AC pathology; it is often positive with impingement syndrome. Pain should be confirmed anteriorly because this maneuver will cause posterior pain if posterior capsular tightness is present.

Paxinos test: Anteroposterior translation of the AC joint. Combined with a bone scan, this test was found to be the most predictive factor for AC joint pathology.17

Diagnostic AC injection: Elimination of symptoms is diagnostic of AC pathology and prognostic for successful distal clavicle resection.

A complete physical examination of the shoulder should be performed to evaluate associated pathology and to rule out other differential diagnoses (as described in the following text).

Coexisting rotator cuff tears may be present in over 80% of patients, labral pathology in over 30%, and biceps pathology in over 20%.3

Impingement syndrome commonly coexists with or may mimic AC pathology, and awareness of this possibility should be used to rule out its existence.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

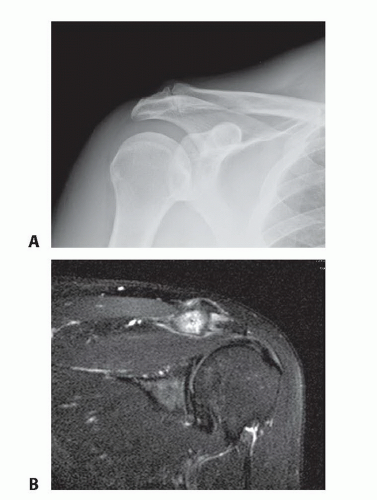

The AC joint is best evaluated radiologically with a Zanca view. This provides an unobstructed view of the AC joint by tilting the x-ray beam 10 to 15 degrees cephalad of the normal shoulder anterior-posterior view (FIG 1A).

Characteristic radiographic changes of primary and posttraumatic arthritis of the AC joint include osteophyte formation with trumpeting of the distal clavicle, sclerosis, and subchondral cyst formation. Narrowing of the AC joint will also be present; however, this occurs as a normal part of aging.

Rheumatoid arthritis affecting the AC joint would typically show periarticular erosions and osteopenia with less spurring than osteoarthritis.

Distal clavicle osteolysis characteristically shows osteopenia, cystic changes of the distal clavicle, and widening of the joint space with narrowing of the distal clavicle.

The supraspinatus outlet view may show inferior clavicular osteophytes, which may contribute to outlet impingement syndrome.

The axillary lateral view of the shoulder may show anterior or posterior displacement of the clavicle, indicative of trauma to the AC joint.

Three-phase technetium bone scan is highly sensitive and specific for AC joint pathology.

Bone scan is especially useful in diagnosing AC pathology that is not evident with conventional radiography.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is sensitive in identifying AC pathology but has poor specificity as AC abnormalities are frequently observed in clinically asymptomatic patients. Reactive edema in the AC joint is more predictive of clinical symptoms than are MRI findings of degenerative changes in the AC joint (FIG 1B).14

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Intrinsic AC pathology

Primary osteoarthritis

Posttraumatic arthritis

Inflammatory arthritis

Crystal-induced arthritis

Septic arthritis

Distal clavicle osteolysis

Intrinsic shoulder pathology

Impingement syndrome

Rotator cuff tears

Biceps lesions

Glenohumeral arthritis

Early adhesive capsulitis

Musculoskeletal tumors of the distal clavicle and proximal acromion

Extrinsic conditions

Cervical spine disorder

Referred visceral problems (cardiac, pulmonary, or gastrointestinal disorders)

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

The initial management of painful AC pathology should be conservative and should include a combination of activity modification, ice or heat therapy, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications, corticosteroid injection, and physical therapy.

Activity modification should focus on avoiding the inciting painful activities. Some patients may be successfully treated nonoperatively with activity modification.

Intra-articular corticosteroid injection with 1 mL of 1% lidocaine and 1 mL of corticosteroid is effective in relieving AC joint pain, but the duration of relief is variable. Patients may receive multiple injections.

Physical therapy consisting of terminal stretching and rotator cuff strengthening may be effective if a concomitant impingement syndrome exists. Isolated AC pathology typically does not respond to physical therapy.

Patients should undergo 3 to 6 months of conservative management before operative intervention.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree