The treatment of scars has an historical base in Oriental medicine. Often, the treatment of scars can be the key to the successful resolution of chronic, persistent, and intractable conditions. All scars are inherently a malformation in normal cellular skin. They are matrices of collagen, blood vessels, and sometimes, foreign objects or toxins that have been deposited in a disorderly fashion. This constitutes the scarred tissue.

The way a scar develops depends on many factors. The most common factors tend to be the nature and severity of the original injury, the surgeon’s skill or method of treatment, if any, that the scar received, how the person’s body heals, the blood supply to the area, the direction of scar formation, and the color of one’s skin.

According to Oriental medicine, essentially, scars can be viewed as “potential” organ-channel disturbances, that is, as potential physical or energetic disturbances of a channel precipitated by the trauma induced to the tissues. The disruption in energy flow in the skin, muscles, and underlying channels can then cause organic or energetic pathology of the local affected areas, internal and external channel pathways, corresponding zang fu organs and even distal sites.

Not all scars cause problems. Many are only superficial, or have healed such that the energy flow of the body is not affected. In general, factors such as scar size, abnormal coloration, lumpiness, and sensations associated with the scar, such as numbness, tingling, itchiness, heat, cold, achiness, and tendon/muscle restriction, indicate that the scar may need treating. Ultimately however, palpation of the discrete borders of the scar is the test to determine its clinical significance.

To evaluate the effects of scar tissue in relation to bodily health, first perform the scar evaluation described below:

- Ask the patient if they have any scars. Remind them of possible scars from surgeries, injuries, and even vaccinations. Scars that are especially significant are found on the face, neck, scalp, back, and abdomen because of the major channels that traverse them.

- Next, with your index finger, palpate all around the borders of the scar, at each place where your finger will fit. Press the tissue at about a 45° angle towards the scar at a moderate depth (about 0.5 in). If any area of the scar is tender, it may indicate qi and/or blood stagnation, qi and/or blood vacuity, or the accumulation of phlegm (calcification). Without the need to arrive precisely at a diagnosis, what is significant about the scar is the tenderness or pain at the affected area. This needs to be resolved since the lack of free-flowingness of energy may have significant effects on local and/or distal organs or sites.

There are numerous ways to treat scars. For convenience, the most common are described in Table 14.1. More information on scar treatment may be found in The Art of Palpatory Diagnosis in Oriental Medicine.1

Before proceeding to treat with any modality, the following guidelines, cautions, and contraindications must be kept in mind:

- Do not treat scars that are still healing (less than a month old) to decrease the risk of infecting the scar.

- Observe clean needle technique so as not to infect the scar. Carefully treat scars in the elderly, diabetic patients, cancer patients, and those with neurological disorders or a weak constitution.

- Initially, only treat two tender areas of the scar until you can evaluate the effectiveness of scar treatment on the patient. In re-equilibrating energy in a scar, blocked energy may be released, leading to energy surges that the patient may perceive as a problem. For example, treating a scar on the gall bladder channel may release energy that goes to the head and produces a headache as the energy in the channel becomes unblocked.

| Method | Instructions |

| External liniments | The application of external liniments and other products can aid in scar healing and reduce the imperfect formation of the epidermis. For convenience, liniments can be applied before bedtime so they have the chance to work for a relatively long period overnight. Useful liniments and their energetics include the following: Zheng Gu Shui—the deepest penetrating of all the Chinese liniments, it penetrates to the bone. It moves blood stasis, promotes healing via improved circulation, and stops pain Vitamin E (d-alpha tocopherol—don’t use synthetic vitamin E designated by “acetate”). Vitamin E reduces superficial scarring and promotes normal tissue re-growth Aloe vera reduces scar formation, inflammation and swelling, and improves wound-healing capacity Ching Wan Hung promotes new tissue growth, reduces scarring and inflammation, and fights bacteria Wan Hua Oil activates blood stagnation and swelling caused by trauma |

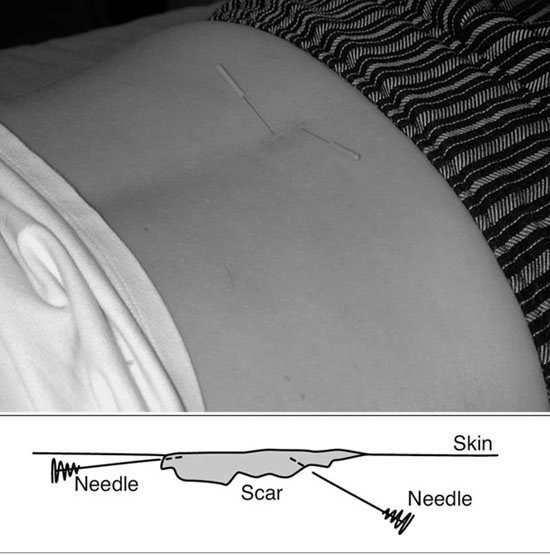

| Needles | Before needling, palpate around the border of the scar and find the two most painful places. After swabbing those points with alcohol, insert a #1 (36 g) 30mm (1 in) Seirin needle transversely (subcutaneously) underneath the scar to a depth of about 0.5 in. I prefer to use the thinnest needles to re-establish subtly even the minutest energetic pathways. However, if the scar is dense, thick, and fibrous a #3 or #5 gauge needle may be used so as not to bend or break the needle. Do not obtain de qi sensation, nor tonify nor disperse, but rather move the needle underneath the scar, then pull out and then repeat insertion two to three times. What the needle is used for is to break up obstruction mechanically if present or to stimulate the affected area. Stop at that depth or when resistance is felt. Retain the needles 5 to 10 minutes and remove. Continue this style of treatment during patient visits until no tender spots remain, at which point the scar is considered non-problematic. See Figure 14.1a and b for an illustrations of needle placement |

| Intradermal needles | In place of acupuncture needles, intradermal needles may be substituted. Follow the preliminary procedure as described under “Needles” above, which is to use palpation as the method to determine which two points to treat. Then using tweezers or forceps for support, insert a 0.6mm Spinex intradermal needle under the scar. Secure the intradermal with Dermicel tape. Intradermals may be retained for take-home therapy or used in the office. However, do not retain intradermal needles on areas where clothing or physical activity may bend or displace them, i.e., at the wrist level, ankles, etc. Observe all standard precautions for the use of intradermals such as number of days to retain, avoiding getting wet, etc. |

| Tiger thermie warmer | The tiger thermie warmer is one of the most effective methods of scar treatment because it can be used to treat the entire scar versus two discrete points at a time as in needling. The tiger thermie warmer is a unique instrument that not only confers the therapeutic benefits of moxa directly onto the skin for penetration, but also simultaneously breaks up physical or energetic tension through the method of massage application with the tool. To appreciate and evaluate the effectiveness of the tiger thermie warmer, first palpate the borders of the scar looking for areas of tenderness. Travel around the borders of the scar with the tiger thermie warmer using light pressure on each discrete point. Move from point to point. Frequently check the temperature of the tiger thermie warmer to avoid burning the patient’s skin. Apply the moxa to the scar borders for 1.5–3 minutes: the longer time for a larger scar. Following the moxa therapy, re-palpate the scar borders—there should be a reduction in tenderness. The area should get slightly pink and the patient should enjoy the relaxing treatment. Continue this approach in the office or instruct patients how to treat themselves daily or when convenient until no more tender spots remain |

Table 14.1 Methods of scar treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree