1

English version

This text is divided into three sections. The first section is devoted to the diagnosis of shaken baby syndrome (revealing signs, risk factors, investigations to be performed, possible lesions, etc.) and ends with suggested diagnostic criteria based on the infant’s clinical history and lesions.

The second section looks at whether certain mechanisms, The second section looks at whether other mechanisms (some of which are often cited, such as being dropped often-cited(such as being dropped or the performance of resuscitation manoeuvres) can induce injuries similar to those seen in shaken baby syndrome. It also looks at whether certain factors can favour the occurrence of injuries.

The third and last section focuses on the consequences (according to French regulations and legislation) of a diagnosis of shaken baby syndrome.

1.1

Abbreviations

AHI

abusive head injury

CIVI

Commission d’indemnisation des victimes infraction pénale (offense Victim Compensation Commission)

CRIP

Cellule de recueil, de traitement et d’évaluation des informations préoccupantes (County Child Abuse Prevention Office)

EDH

extradural haematoma

ESAS

enlargement of the subarachnoid space

HI

head injury

ITT

temporary total incapacity

MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

OPP

ordonnance de placement provisoire (temporary care order)

RH

retinal haemorrhage

SBS

shaken baby syndrome

SDH

subdural haematoma

1.2

Participants

This public audition was organized by the SOFMER (the French Society for Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine), with the participation of the following bodies:

- •

National College of Lecturers in General Practice

- •

Inserm – The French National Institute of Health and Medical Research

- •

InVS – The Health Surveillance Institute

- •

The French Society for Anaesthesia and Resuscitation

- •

The French Society for Emergency Medicine

- •

The French Society for Forensic Medicine

- •

The French Society for Paediatric Neurosurgery

- •

The French Academy of Neuropediatrics

- •

The French Academy of Pediatrics

- •

The National Union of Associations of Families of Victims of Brain Injury (UNAFTC)

1.2.1

Funding

- •

The Provincial Liberal Professions Health Insurance Fund

- •

The General Directorate for Health

- •

France Traumatisme Crânien

- •

The French Society for Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (SOFMER)

- •

The French-Language Society for Paediatric Handicap Research (SFERHE)

- •

The Île-de-France Liberal Professions Health Insurance Fund

1.2.2

Organizing Committee

- •

Dr Anne Laurent-Vannier, physical and rehabilitation medicine specialist, Saint-Maurice – Chairperson of the Organizing Committee

- •

Dr Juliette Bloch, epidemiologist, InVS, Saint-Maurice

- •

Thierry Boulouque, Division Commissioner, Head of the Child Protection Unit, Paris

- •

Dr Jeanne Caudron-Lora, emergency physician, Créteil

- •

Professor Brigitte Chabrol, paediatrician, Marseille

- •

Frédéric De Bels, HAS, Saint-Denis La Plaine

- •

Dr Patrice Dosquet, HAS, Saint-Denis La Plaine

- •

Françoise Forêt, Honorary Professor, National Union of Associations of Families of Victims of Brain Injury (UNAFTC), Paris

- •

Dr Jose Guarnieri, neurosurgeon, Valenciennes

- •

Professor Vincent Gautheron, physical and rehabilitation medicine specialist, Saint-Étienne

- •

Dr Cyril Gitiaux, paediatrician, Paris

- •

Anne-Sophie Jarnevic, magistrate, Chartres

- •

Thérèse Michel, social worker, Tours

- •

Professor Gilles Orliaguet, specialist in anaesthesia and resuscitation, Paris

- •

Dr Claude Rougeron, general practitioner, Anet

- •

Professor Michel Roussey, paediatrician, Rennes

- •

Yvon Tallec, magistrate, Paris

- •

Professor Gilles Tournel, forensic physician, Lille

- •

Dr Anne Tursz, Research Director, Inserm, Villejuif

1.2.3

Hearing Commission

- •

Dr Mireille Nathanson, paediatrician, Bondy – Co-Chairperson of the Hearing Commission

- •

Fabienne Quiriau, Director of the National Convention of Child Protection Associations (CNAPE), Paris – Co-Chairperson of the Hearing Commission

- •

Aurélie Assie, social worker, Paris Child Assistance Unit, Family Reception Service, Ecommoy

- •

Dr Joseph Burstyn, ophthalmologist, Paris

- •

Dr Christine Cans, paediatrician, Grenoble

- •

Dr Catherine Arnaud, paediatrician, Toulouse

- •

Violaine Chabardes, gendarme (police officer), Lyon

- •

Hélène Collignon, journalist, Paris

- •

Dr Marie Desurmont, forensic physician, Lille

- •

Isabelle Gagnaire, childcare nurse, Saint-Étienne

- •

Professor Nadine Girard, radiologist, Marseille

- •

Professor Etienne Javouhey, resuscitation specialist, Lyon

- •

Dr Anne Laurent-Vannier, physical and rehabilitation medicine specialist, Saint-Maurice

- •

Dr Caroline Mignot, paediatrician, Paris

- •

Philippe Lemaire, magistrate, Riom

- •

Dr Sylviane Peudenier, neuropaediatrician, Brest

- •

Dr Bruno Racle, paediatrician, Versonnex

- •

Dr Pascale Rolland-Santana, general practitioner, Paris

- •

Dr Thomas Roujeau, neurosurgeon, Paris

- •

Dr Nathalie Vabres, paediatrician, Nantes

- •

Roselyne Venot, police officer, Versailles

1.2.4

Literature review coordinators

- •

Dr Elisabeth Briand-Huchet, paediatrician, Clamart

- •

Jon Cook, anthropologist, Villejuif

1.2.5

Experts

- •

Professor Thierry Billette de Villemeur, paediatrician, Paris

- •

Professor Jean Chazal, neurosurgeon, Clermont-Ferrand

- •

Professor Catherine Christophe, radiologist, Brussels

- •

Dr Sabine Defoort-Dhellemmes, ophthalmologist, Lille

- •

Dr Gilles Fortin, paediatrician, Montreal

- •

Dr Caroline Rambaud, forensic physician, Garches

- •

Professor Jean-Sébastien Raul, neurosurgeon, Strasbourg

- •

Dr Caroline Rey-Salmon, paediatrician, Paris

- •

François Sottet, magistrate, Paris

- •

Elisabeth Vieux, honorary magistrate, Paris

- •

Professor Mathieu Vinchon, neurosurgeon, Lille

- •

Professor Rémy Willinger, Professor of Biomechanics, Strasbourg

Illustrations supplied by the Société Francophone d’Imagerie Pédiatrique et Prénatale (SFIPP).

1.3

Guidance report. Shaken baby syndrome: the diagnostic work-up

1.3.1

The definition of shaken baby syndrome

SBS is a type of inflicted, non-accidental or AHI caused by shaking . The syndrome mainly occurs in infants under 1 year of age. The three studies with the largest number of cases are King et al. in Canada in 2003 , Mireau in France in 2005 and the Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program (PCSP) in 2008 . The median age was 4.6 and 5 months in King et al. and the PCSP , respectively, whereas the mean age reported by Mireau was 5.4 months (the youngest infants in the latter study were 1 month old).

The literature data mainly concern AHI and not just SBS. Hence, some of the answers below are related to AHI in general.

The incidence of SBS varies between 15 and 30 per 100,000 infants under 1 year of age . When related to the number of the births in France, one can estimate that 120 to 240 infants a year may be concerned by this form of abuse. However, there are no epidemiological data for France; Mireau suggested a figure of 180 to 200 cases a year .

The published figures almost certainly underestimate the true incidence:

- •

the figures are mainly related to the most severe cases, which are probably also underreported;

- •

the lack of an autopsy in all suspicious infant deaths rules out certain diagnoses in some cases;

- •

it is often difficult to differentiate between abusive and accidental head injuries.

Missed diagnoses increase the risk of recurrence of abuse, as mentioned by a few publications ; a recent, retrospective study of 112 children identified the recurrence of SBS (from two to 30 times, with an average of 10 times) in 55% of cases.

1.3.2

Which elements (clinical signs, context, risk factors, etc.) are or may be suggestive of a diagnosis of shaken baby syndrome or may lead to misdiagnosis?

1.3.2.1

Initial signs and symptoms

There is major clinical heterogeneity:

- •

in the most serious cases, the child is found dead. The procedures to be followed in this event are specified below;

- •

the child presents signs that immediately suggest serious neurological damage, prompting immediate treatment:

- ∘

convulsions,

- ∘

severe malaise described by the parents (“I thought that my child was going to die”, “my child stopped breathing”) or observed by the physician (serious consciousness disorders, respiratory pauses, bradycardia),

- ∘

impaired vigilance (extending to coma),

- ∘

severe apnoea: very specific for AHI vs. accidental HI (in the study by Maguire et al. , the positive predictive value is 93%),

- ∘

fixed upward gaze,

- ∘

signs suggesting acute intracranial hypertension or even imminent herniation: postural disorders (decortication or decerebration, episodes of hypertonia), bradycardia, arterial hypertension, respiratory rhythm disorders;

- ∘

- •

the child presents signs that suggest neurological damage:

- ∘

changes in muscle tone (axial hypotonia),

- ∘

poor contact (the child does not respond well to stimuli and/or no longer smiles),

- ∘

a decrease in the child’s capabilities,

- ∘

increased head circumference, with a sudden change in the percentile class in the growth chart (which emphasizes the value of keeping a regularly updated family health notebook),

- ∘

a bulging fontanel;

- ∘

- •

the child presents non-specific signs that can lead to misdiagnosis:

- ∘

behavioural changes described by carers: crying, moaning, irritability, changes in sleep or feeding patterns, less smiling,

- ∘

vomiting,

- ∘

respiratory pauses,

- ∘

pallor,

- ∘

suspected pain.

- ∘

In all cases, the clinical examination must be thorough and performed after undressing the child; in particular it should include palpation of the fontanel, measurement of the head circumference (which should be checked against the growth chart) and examination of the whole body (including the scalp) for bruises.

Given the lack of specificity of several of these signs, a combination of signs may provide much more information ( Table 1 ). Thus, vomiting (which is a very frequent and banal symptom) is a warning sign if combined with a bulging fontanel, axial hypotonia, vigilance disorders and a shift towards the top of the head circumference curve.

| Signs observed | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Axial hypotonia and an epilepsy attack | 53 |

| An epilepsy attack and bulging fontanel | 46 |

| Vomiting and bulging fontanel | 38 |

| Vomiting and axial hypotonia | 34 |

| A shift towards the top of the head circumference curve and bulging fontanel | 31 |

| Vomiting, an epilepsy attack and bulging fontanel | 25 |

| Vomiting and vigilance disorders | 24 |

| Vomiting, axial hypotonia and bulging fontanel | 23 |

| Vomiting, vigilance disorders and bulging fontanel | 19 |

The child’s medical history (family health notebook) should also be screened for the above-mentioned signs, since they may testify to previous HI.

Certain items of information in the infant’s medical history can suggest the occurrence of an AHI:

- •

a delay in seeking medical assistance and/or a lack of responsiveness by the family/carers;

- •

an absence of explanations for the observed clinical signs:

- ∘

in the series reported by Mireau , the family/carers did not report any trauma at all in 71.6% of the cases, despite repeated questioning,

- ∘

according to Hettler and Greenes , the fact that a history of trauma is not immediately reported is very discriminant for AHI, compared with non-inflicted (accidental) HI [in 69.3% and 3% of cases, respectively ( P < 0.001), with a high specificity (0.97) and a high positive predictive value (0.92)];

- ∘

- •

more suggestive, implausible explanations: for example, bruising supposedly related to a fall in an infant who cannot yet walk unaided;

- •

an explanation that changes over time or differs from one person to another;

- •

spontaneous reporting of a mild HI;

- •

a child who reportedly cries a lot or a prior consultation for crying;

- •

a history of trauma of any sort;

- •

a history of unexplained sibling death.

If the physician suspects a diagnosis of SBS, he/she must tell the parents about his/her concern for the child’s status and inform them that emergency hospitalization is indicated.

1.3.2.2

Is there a lucid interval between the shaking and the onset of symptoms?

A variety of studies have established that there is no lucid interval in most cases:

- •

Willman et al. performed a retrospective study of 95 children having suffered a fatal HI and concluded that there was no lucid interval (except for the cases with EDH);

- •

Starling et al. established that in cases where shaking (with or without impact) had been admitted, the symptoms appeared immediately after the trauma 52 times out of 57. In five cases, it was difficult to date the symptom onset but it must have been within 24 hours of the shaking;

- •

according to Biron and Shelton’s study of 52 cases of shaking investigated by the police and considered to be “serious”, the symptoms were immediate in cases with a full description.

It appears thus that in the great majority of cases of SBS (or perhaps even in all cases), shaking immediately leads to symptoms. Of course, it must be borne in mind that the consultation may take place some time after shaking has occurred.

1.3.2.3

Risk factors for abusive head injury

It is important to remember that a risk factor is a variable with a statistically significant association with a phenomenon, disease or syndrome but is not the cause.

1.3.2.3.1

Risk factors related to the child

The gender ratio: there is male predominance, with a boy/girl ratio of between 1.3 and 2.6.

Prematurity: there is a higher proportion of premature infants among SBS victims (11 to 21%, with 11% in the series reported by Mireau ) than among the general population (7 to 8%).

Multiple pregnancies are more frequent in SBS (in 5% of cases reported by Mireau ) than in the general population (1.5% of all births).

Crying cannot be considered as a risk factor per se but may trigger abuse of the infant , given that parents’ tolerance of crying in a child is very variable. A consultation for crying in a young baby should not only search for the cause but also evaluate the parents’ feelings and reactions.

1.3.2.3.2

Risk factors related to the shaker

In cases where the perpetrator has been identified (regardless of whether he/she has admitted the act), the latter is usually (70%) male (more often the child’s father than the mother’s partner).

Unrelated adults also constitute a significant category of potential shakers: in the series of 151 AHI cases examined by Starling’s group , the mother’s partner was implicated in 20.5% of cases and a female carer/babysitter was implicated in 17.3% of cases.

1.3.2.3.3

Risk factors related to the parents

In terms of the socio-economic context, the results are very contradictory. All backgrounds are concerned by SBS but the suggested vulnerability factors remain to be documented (a first child, a new pregnancy, a return to work, poor knowledge of a child’s needs or normal behaviour, social and family isolation, a history of domestic violence, past or current psychiatric disorders, drug or alcohol abuse, etc.). In 2005, Mireau noted that the parents had very poor knowledge of a child’s needs or normal behaviour. Low parental age is frequently emphasized by researchers and has been reported as a potential risk factor .

A prospective study examined the socio-economic context of 25 cases of non-accidental HI observed over almost 10 years (January 1998 to September 2006) in a region of Scotland: 76% of the cases came from the most deprived areas in terms of education, learning and social capacities, with 72% in areas with the highest crime rates, 68% in areas with poor healthcare facilities, 60% in low-income areas, 52% in areas with poor housing and 48% in areas with high unemployment.

These results are in sharp contrast to those of earlier studies: of the two studies published in 2000 on the same cohort of children, one noted that most parents had a stable job (81% of the mothers were in work) and the other found that the majority of the parents had been in secondary or higher education.

Ruling out a diagnosis of AHI because of an apparently favourable sociofamilial context may lead to so-called “missed” diagnoses .

However, in general, a healthcare professional should pay attention to a difficult sociofamilial context for the child’s carers.

The relationship between SBS and ethnic factors has been studied. Fortin reviewed the literature on this topic and concluded that ethnic origin is no more significantly associated with SBS than it is with accidental HI. In fact, the data suggested rather that the “ethnic origin” parameter constituted a risk factor for other social markers that increased in the risk of AHI in the child.

In summary , the currently available data (although fragmented and sometimes contradictory) suggest that children who are male, first born, aged under 6 months, born prematurely after a complicated or multiple pregnancy, living with parents with a history of psychoactive substance abuse (alcohol, drugs) or family violence and/or with poor knowledge of strategies for managing the relationship with their infant are at a greater risk of being SBS victims. Of course, this violent act can occur in the absence of any socio-economic and cultural risk factors. Even though it is right to consider that SBS victims are more likely to belong to one or more of the above-mentioned risk groups, it is wrong to believe that the majority of children presenting these characteristics are victims of this type of abuse.

1.3.3

What types of lesions occur and which clinical and paraclinical assessments are necessary and sufficient to detect them?

1.3.3.1

The lesions

1.3.3.1.1

The meninges (with subdural or subarachnoid haemorrhage), the brain, the eyes and the spinal cord are likely to be damaged in SBS

Other lesions may also be observed: fractures of the limbs, ribs or skull; bruising of the scalp, hematoma of the neck muscles and posterior spinal lesions.

Although the most detailed data have been provided by autopsy series, the latter obviously correspond to the most serious forms of SBS because they have led to the child’s death.

On the basis of 93 neuropathological examinations of SBS victims lacking visible cranial trauma, Billette described:

- •

81 cases of subdural hematoma (SDH), 65 cases of subarachnoid haemorrhage, 14 cases of intraparenchymatous haemorrhage, 69 cases of brain oedema and 41 cases of cerebral herniation;

- •

56 cases of intraocular haemorrhage;

- •

21 spinal cord lesions.

The state of the spine was not mentioned. The lesions observed here were not specific for the mechanism of death.

Another study found cervical epidural haemorrhages and focal axonal lesions of the brain stem and the roots of the spinal nerves in 11 of 37 AHI cases and in none of 14 control cases (i.e. deaths from other causes).

Different types of damage to the brain parenchyma can be observed:

- •

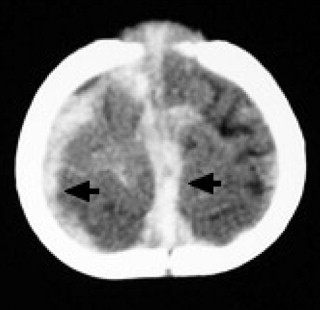

anoxic lesions of the cortex, grey nuclei and thalamus: these lesions translate into (rarely haemorrhagic) hypodensities associated with a loss of contrast between white matter and grey matter ;

- •

brain oedema, translating into a decrease in the volume of liquid-filled spaces;

- •

contusions, in particular in the frontal and temporal regions and at the white matter–grey matter junction.

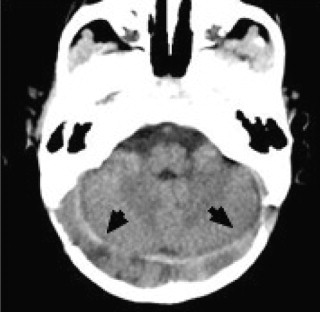

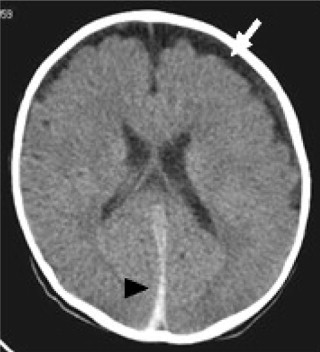

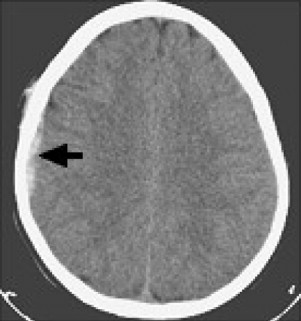

Intracranial extra-axial, blood collections (SDH, potentially combined with subarachnoid haemorrhage) present some particular features in SBS ( Figs. 1–3 ). They are generally multifocal, bilateral and faint (with no mass effect). They cover the convexity of the brain hemispheres and accumulate in the longitudinal fissure in an inclined position and along the insertion of the tentorium cerebelli. The detection of a haemorrhage in the falx cerebri is very suggestive of SBS , as are subdural collections in the posterior fossa. It is nevertheless noteworthy that SDH is not observed in all shaken babies: it was only seen in 72–93% of the cases in the articles reviewed by Christophe .

EDH results more from accidental HI than SBS, where it is extremely rare.

1.3.3.1.2

Eye lesions

RHs are NOT always present in SBS: according to Defoort-Dhellemmes , they are seen in about 80% of cases (ranging from 50 to 100%, depending on the series). They are described in terms of:

- •

whether they are bilateral or not: most are bilateral, which contrasts with the generally unilateral RH that can be observed in accidental HI . Nevertheless, RH are unilateral in 10 to 17% of cases of SBS;

- •

their appearance, size (small, large, more or less than two optic discs) and shape (flame-shaped, blots, punctiform, dome-shaped), which depend on their location in the eye;

- •

their location at the posterior pole of the eye (peripapillar, macular, along the vascular arcades) or at the periphery of the fundus (near to the periphery or extending out across the very edge to the ora serrata);

- •

their location relative to the retinal layers ( Table 2 ):

- ∘

dome-shaped, preretinal haemorrhages situated just under the internal limiting membrane, whether small (classic, pearl-shaped RH) or large (haemorrhagic retinoschisis),

- ∘

superficial haemorrhages (that disappear very rapidly, sometimes in less than 24 hours) or deep intraretinal haemorrhages,

- ∘

subretinal haemorrhages.

- ∘

| Preretinal haemorrhages | Dome-shaped, small (< 1 optic disc diameter) |

| Dome-shaped, large (> 1 optic disc diameter) | |

| Haemorrhagic retinoschisis | |

| Intraretinal haemorrhages | Superficial intraretinal |

| Deep intraretinal | |

| Subretinal haemorrhages | |

Defoort-Dhellemmes distinguishes between three types of RH, depending on their number and their extent ( Table 3 ):

- •

type 1: intraretinal haemorrhages, flame-shaped, blots or punctiform, situated at the posterior pole of the eye;

- •

type 2: preretinal dome-shaped haemorrhages that are small (no larger than the diameter of the optic disc) and pearl-shaped, situated at the posterior pole, around the optic disk and along the vascular arcades or mid-way out towards the periphery. These haemorrhages may occur alone or in combination with type 1 RH;

- •

type 3: profuse, multiple haemorrhages of all types (intra-, pre- or subretinal), coating the whole retina or flecked out to its periphery, combined with unilateral or bilateral premacular haemorrhagic plaques (which are sometimes immediately suggestive of haemorrhagic retinoschisis). Type 3 haemorrhages are extremely suggestive of SBS. They can be considered as almost pathognomonic, especially when combined with SDH, massive brain oedema or bone lesions that are very suggestive of abuse. However, they can be observed extremely rarely in violent, accidental HI (road accidents).

| Type 1 | Intraretinal haemorrhage (flame-shaped, blots or punctiform, situated at the posterior pole of the eye |

| Type 2 | Small, dome-shaped, preretinal haemorrhage, situated at the posterior pole of the eye, around the optic disk and along the vascular arcades or mid-way out towards the periphery. They may occur in isolation or in combination with Type 1 RH |

| Type 3 | Profuse, multiple haemorrhages of all types (intra-, pre- or subretinal) coating the whole retina or flecked out to its periphery, combined with unilateral or bilateral premacular haemorrhagic plaques |

Other lesions can be seen in the fundus: vitreous matter and choroidal haemorrhage and papillary oedema due to intracranial hypertension.

Intra-orbital haemorrhage (scleral haemorrhage and haemorrhage of the optic nerve sheath, muscles and orbital fat) can be detected on autopsy .

1.3.3.1.3

Lesions of the neck muscles, spine or spinal cord

Neck damage was noted in 4% of the children studied by King et al. . Billette reported that several observations of spinal cord SDH have been described in the literature. Christophe pointed out that violent shaking can provoke: (i) widespread axonal lesions near the brain stem and the upper spinal cord and (ii) epidural haematoma near the neck/head junction.

1.3.3.1.4

Skin lesions

In the absence of medical causes, bruising is very suggestive of abuse in an infant that cannot yet walk unaided . In the latter article, only 0.6% of the children under 6 months and 1.7% of the children under 9 months of age had one or several bruises. It is particularly important to look for bruising on the scalp: in a study on HI in infants, Greenes and Schutzman found that 93% of the infants presenting bruising of the scalp also had intracranial lesions.

1.3.3.1.5

Bone lesions

Bone lesions are particularly suggestive of abuse:

- •

rib fractures (in the absence of prior, aggressive, respiratory physiotherapy) are posterior, at the costovertebral junction. There are generally multiple fractures on contiguous, symmetric ribs;

- •

metaphyseal fractures;

- •

periosteal spurs;

- •

some skull fractures: multiple fractures and depressed occipital fractures.

1.3.3.2

Clinical and paraclinical assessments

1.3.3.2.1

Clinical assessments

Check and update the height, weight and head circumference curves.

Thorough clinical screening for trauma, which must be photographed if found.

A neurological examination is, of course, essential; one should note the head circumference (in comparison with earlier figures), the state of the fontanel, axial tone and possible motor impairments.

1.3.3.2.2

Additional assessments

When faced with neurological clinical signs or a combination of the signs described above, the following additional examinations are required:

- •

a computed tomography (CT) brain scan is the first-line examination in an emergency . It is a sensitive method for detecting haemorrhagic lesions: SDH, subarachnoid haemorrhage and (more rarely) haemorrhages of the brain parenchyma. The brain scan can also define the extent of any oedema. If symptoms persist (and even when the first scan is normal) a second scan can be performed 12 to 24 hours later;

- •

an ophthalmological examination: it must be performed after dilatation, by an experienced ophthalmologist, within 48 to 72 hours at the latest (due to the rapid resorption of some types of RH). Photos must be taken whenever possible;

- •

the value of MRI:

- ∘

when performed in the acute phase as soon as permitted by the child’s state, MRI is of significant diagnostic value for revealing lesions that are not visible on CT (i.e. small SDH, oedema and hypoxic lesions). Performance of an MRI scan depends on the child’s clinical state (stability). This is the examination of choice for having a complete overview of axial and extra-axial lesions, whether haemorrhagic or not . MRI enables the brain stem, spinal cord and neck region to be assessed, in addition to the brain itself.

Kemp et al. reviewed the literature on children with severe spinal cord damage (24 children described by 15 studies) and recommended that head and neck MRI should be performed in any infant in whom HI is suspected, especially if there is unexplained deformation of the spine, focal neurological signs or skeletal lesions.

Useful conventional sequences include the T1- and T2-weighted spin-echo sequences and the T2* echo gradient sequence. All are sensitive to the paramagnetic effect of the haemoglobin degradation products and enable determination of the approximate age of intraparenchymatous haemorrhage.

The fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence is very good for detecting subarachnoid haemorrhage and small SDH .

So-called “advanced” techniques (such as magnetic susceptibility imaging, spectroscopy and diffusion imaging) have further increased the sensitivity and the diagnostic and prognostic value of MRI:

- –

magnetic susceptibility imaging can visualize very small areas of bleeding, whether recent or old ,

- –

spectroscopy can provide information on anatomical and functional damage to neurons and axons ,

- –

diffusion imaging can estimate changes in the volume and configuration of extracellular spaces and/or intracellular viscosity ,

- –

studies on SBS have demonstrated that early anomalies in diffusion imaging are compatible with cytotoxic-type oedema – probably as part of an associated ischaemic, hypoxic encephalopathy ;

- –

- ∘

it is less urgent to perform MRI as part of the lesion screening process but it must be performed before discharge from hospital. The brain stem, spine and spinal cord must be studied and not just the brain. Furthermore, the MRI can reveal hypoxic lesions and lesions of different ages;

- ∘

- •

other necessary examinations:

- ∘

a complete blood count + platelet count, PT, APTT, coagulation factors,

- ∘

X-rays of the whole skeleton, performed according to the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines . A skeletal survey is mandatory in all cases of suspected physical abuse in children younger than 2 years (not a “whole body” X-ray): radiographies of the axial skeleton (anteroposterior and lateral views of the thorax, and possibly an oblique view to see the ribs, the upper dorsal and lumbar spine; anteroposterior and lateral views of the pelvis, in order to see the medial lumbar spine; a lateral view of the lumbosacral spine, anteroposterior and lateral views of the cervical spine, anteroposterior and lateral views of the skull [and other views, if necessary]) and all limb segments. One should thus screen for recent or older fractures – particularly in the locations suggestive of SBS cited earlier.

There are then three possibilities: the bone lesions are (i) very suggestive of abuse or (ii) not typical or (iii) absent. In the last two cases and if abuse is strongly suspected, scintigraphic examination can reveal lesions that are not visible on X-rays (e.g. rib fractures that do not yet show callus formation, very small diaphyseal fractures and early periosteal thickening). Another option (if the child can be placed in a safe environment) is to repeat the skeletal X-rays 10 or 15 days later and see whether there are any changes .

- ∘

If the child is dead on admission to the hospital, the family/carers must be questioned as to any abnormal signs in the hours or days before death. In February 2007, the French National Authority for Health (HAS) recommended performing the following examinations (in addition to an analysis of the circumstances in which the child was found and the medical history) in all cases of unexpected infant death: a thorough clinical examination, a fundoscopy and an X-ray examinations by a paediatric radiologist (X-rays of the skull, spine, pelvis, all four limbs and the thorax) and CT or MRI imaging of the brain and, if possible, the whole body. Autopsy is essential but requires the parents’ consent (unless otherwise decided by the district prosecutor for forensic and legal reasons) and so must always be suggested. It must include a fundoscopy and a neuropathological examination of the brain, eyes and spinal cord. Several authors have described autopsy techniques in the young child . Ehrlich et al. insist on the need to evidence rupture of the corticodural veins. Several techniques for this have been suggested .

Some time after shaking, certain neurological or neuropsychological symptoms and some neuroradiological images can suggest shaking a posteriori. It is then necessary to look for a drop in the head circumference curve (at this stage, microcephaly is observed) and perform MRI.

1.3.4

What are the differential diagnoses for shaking and which clinical and paraclinical assessments are necessary and sufficient for an aetiological diagnosis?

1.3.4.1

The main differential diagnosis is accidental HI. Rarer, disease-related diagnoses must be ruled out

1.3.4.1.1

Disorders of haemostasis

Congenital coagulation disorders (factor V, X or XIII deficiencies and haemophilia A) can lead to intraparenchymatous or extra-axial haemorrhage .

Severe thrombopenia can lead to intracranial haemorrhage (mainly intraparenchymatous haemorrhage).

1.3.4.1.2

Arteriovenous malformations

These are extremely rare below the age of 1 year and trigger subarachnoid haemorrhage (often associated with an intracerebral or intraventricular haemorrhage) rather than subdural haemorrhage.

1.3.4.1.3

Metabolic diseases

Depending on the context, one must screen for:

- •

type 1 glutaric aciduria: 1 in 30,000 births. This condition often manifests itself by acute neurological distress in the first months of life, with a pseudoencephalitic clinical picture in children with macrocephaly and pre-existing hypotonia. Imaging can reveal suggestive anomalies: a broad lateral sulcus and lesions in the central grey nuclei. During disease progression, SDH is frequent and RHs are reported in 20 to 30% of cases . Faced with this characteristic clinical and radiological picture, a diagnosis of this metabolic disease is confirmed by the chromatographic assay of urinary organic acids ;

- •

Menkes disease: this affects boys only (as a recessive, X-linked disease) and is also rare (1 per 250,000–300,000 births). It is a metabolic disease of copper absorption and induces multiple bone lesions, SDH , hypotonia, early convulsions and severe mental retardation in children surviving beyond the neonatal period. The twisted appearance of the hair is suggestive. Serum copper and ceruloplasmin assays make a biochemical diagnosis very easy.

1.3.4.1.4

Osteogenesis imperfecta

Two articles have stated that SDH is possible in this syndrome but did not indicate its frequency and a causal relationship has not been established. The clinical picture is quite different; the constitutive bone fragility results in diaphyseal fractures and not metaphyseal damage.

1.3.4.2

Are retinal haemorrhages required for diagnosis of SBS?

RHs are observed in about 80% of cases of AHI, on average (with values ranging from 50 to 100%, depending on the series).

In fact, the frequency of RH is difficult to estimate because:

- •

as reported in the literature, the frequency increases when the fundoscopy is performed by a senior ophthalmologist on admission to the emergency room, after dilatation or when photos (taken on admission by specialists in paediatric resuscitation) show these haemorrhages;

- •

many ophthalmologic studies consider their presence to be necessary for the diagnosis of SBS – thus introducing circularity bias because the RH is both the subject of the study and an obligatory diagnostic criterion.

One can nevertheless conclude that RH (absent in about 20% of the cases reported by Defoort-Dhellemmes ) are not essential for a diagnosis of SBS. In accidental HI due to road accidents, RHs are much rarer (ranging from 0 to 17%, with a frequency of 8.9% for all the literature cases collated by Kivlin et al. ). However, their frequency has certainly been underestimated, since fundoscopy is not performed systematically in child victims of road accidents or may be performed too late. The most frequent RH in accidental HI corresponds to type 1 and 2 in Defoort-Dhellemmes’ classification and disappear rapidly – sometimes in less than 2 days .

1.3.4.3

Clinical criteria for a diagnosis of shaking

This question can be addressed from two standpoints:

- •

according to the clinical situation;

- •

according to the lesions found upon examination.

1.3.4.3.1

Different clinical situations can suggest a diagnosis of SBS

When an infant is brought in dead and does not correspond to terminal progression of a known pathology , a diagnosis of AHI must always be considered as a potential cause of unexpected death. The interview with the family must be performed with respect but must also be detailed, in order to establish the circumstances surrounding the death.

Some signs must be given special attention:

- •

implausible explanations;

- •

statements that change over time (although the parents’ emotional state can be an explanation);

- •

suspicion of previous abuse and other poorly explained deaths in the family.

For all cases of unexpected infant death, it is advisable to obtain the parents’ consent for an autopsy that will potentially enable collection of data on shaking (bearing in mind that any indication of SBS should be reported to the district prosecutor, who will be able to order an autopsy as part of a forensic procedure).

When faced with inaugural, acute, neurological distress , the clinician should perform a brain CT scan as soon as possible and, if intracranial haemorrhage is evidenced, look for the simultaneous presence of other signs of shaking:

- •

RH;

- •

signs of abuse (skin and/or bone lesions);

- •

explanations given by the family that are implausible or change over time.

If all these signs are found together, the diagnosis of SBS is highly probable, or even certain.

When faced with signs that strongly suggest neurological damage , such as those described above (changes in behaviour, poor food intake, poor contact, less smiling, decrease in the child’s capabilities; change in tone [axial hypotonia] or certain non-specific signs (vomiting, respiratory disorders [pauses, apnoea], pallor or an infant who appears to be in pain), it is essential to consider shaking:

- •

palpation of the fontanel, measurement of the head circumference and examination of the growth curve (acts that must always be performed when examining an infant) can evidence a bulging fontanel and enlargement of the skull with a sharp upwards shift on the head circumference curve;

- •

look for:

- ∘

a combination of the above-mentioned signs ( Table 1 ), found in a significant percentage of cases of shaking,

- ∘

other signs of abuse via clinical examination and analysis of the medical history;

- ∘

- •

note during the interview:

- ∘

the existence of any delay in seeking medical care,

- ∘

the fact that the explanations given by the family/carers are implausible, barely plausible or change over time or from one person to another;

- ∘

- •

look for RH;

- •

perform a brain CT scan immediately (MRI being performed later, when permitted by the child’s state).

Some of these elements may be absent and it is impossible (given our current state of knowledge) to assess the relative importance of each of those elements present. However, certain data have more specific value:

- •

in clinical terms: in addition to the interview data, the existence of apnoea, bruising (on the scalp or elsewhere);

- •

the CT results: subdural or subarachnoid haemorrhages are more frequent (refer to the description above) than intraparenchymatous bleeding and EDH is extremely rare in cases of SBS;

- •

the fundoscopy: the existence of RH of all types (even on one side only; Table 3 ), especially when profuse or flecked across the retina to the outer periphery, combined with one or several large, dome-shaped or plaque-shaped haemorrhages (sometimes with the characteristic aspect of haemorrhagic retinoschisis) or a perimacular retinal fold (Defoort-Dhellemmes type 3, which is almost completely pathognomonic for SBS).

One of these signs alone will not enable the physician to affirm a diagnosis of SBS. The combination of two or more of these signs is strongly suggestive, as long as differential diagnoses have been ruled out. The description of an act of shaking (sometimes by the perpetrator but more often by an eye witness) is, of course, a key element.

In any case, any suspicion of shaking must prompt the physician to tell the parents about his/her concern and the absolute need to hospitalize the child.

1.3.4.3.2

At the end of the clinical and radiological assessments (whatever the initial symptoms), the probability of a diagnosis of SBS will vary according to the lesions observed

In a child under 1 year of age and after having ruled out differential diagnoses:

- •

a diagnosis of shaking is highly probable (or even certain) in cases with:

- ∘

multifocal extra-axial haemorrhages (SDH, subarachnoid haemorrhage) ( Figs. 1–3 ),

- ∘

AND RH that is profuse or flecked across the retina out to its periphery (Defoort-Dhellemmes type 3) ( Table 3 ),

- ∘

AND a clinical history that is absent, incoherent, changes over time or is incompatible with the observed lesions or the child’s age.

The coexistence of these three diagnostic elements (as described here) prompts a diagnosis of AHI (probably by shaking).

Other elements can be present and reinforce the diagnosis of shaking:

- –

hypoxic brain lesions,

- –

cervical lesions (spinal canal haematoma, spinal cord lesions and lesions of the occipitovertebral or cervicodorsal junctions),

- –

description of violent shaking by an eye witness;

- –

- ∘

- •

a diagnosis of shaking is probable in cases with:

- ∘

EITHER multifocal extra-axial haemorrhages ( Figs. 1–3 ), in the presence or absence of RH of any type ( Table 3 ),

- ∘

OR localized extra-axial haemorrhage with type 2 or 3 RH,

- ∘

AND a clinical history that is absent, incoherent, changes over time or is incompatible with the observed lesions or the child’s age;

- ∘

- •

in cases of localized SDH and RH limited to the posterior pole (type 1 RH), with a clinical history that is absent, incoherent, changes over time or is incompatible with the lesions observed or the child’s age, there was no consensus within the Hearing Commission as to whether diagnosis of shaking must be considered as probable or possible;

- •

a diagnosis of shaking is possible in cases with:

- ∘

localized SDH,

- ∘

AND a clinical history that is absent, incoherent, changes over time or is incompatible with the observed lesions or the child’s age;

- ∘

- •

a diagnosis of shaking can be ruled out in cases with:

- ∘

localized SDH ( Fig. 4 ), with a linear fracture and adjacent bruising in some cases,

Fig. 4

Localized right frontoparietal SDH and adjacent bruising of the scalp (indicated by an arrow) in a case of accidental head injury (HI).

- ∘

AND an unchanging clinical history compatible with the observed lesions and the child’s age and which features a description of a violent, accidental HI.

- ∘

In all cases, the observation of any of the following is strongly suggestive of a diagnosis of abuse and should prompt the implementation of appropriate measures:

- •

abuse-specific bone lesions and bruising (particularly on the scalp) in a child too young to walk unaided;

- •

a history of abuse, or of unexpected poorly explained sibling death(s);

- •

a delay in seeking medical assistance.

1.4

The causal mechanism of lesions

1.4.1

In the presence of subdural haematoma (in the presence or absence of subarachnoid haemorrhage) and retinal haemorrhage (alone or combined), which causal mechanisms or circumstances may be invoked?

Since the lesions observed in SBS are not highly specific (even though some are highly suggestive), it is important to determine which lesions can be observed during activities frequently invoked by the adults when a child is brought to hospital after denied shaking. The most frequent explanations are falls and attempts to resuscitate the infant after loss of consciousness. Indeed, some people consider that shaking alone is not sufficient to create lesions and that an accompanying impact is essential. This is why the following question is dealt with here, with a view to facilitating the diagnosis of SBS: which mechanisms or circumstances may be involved in the occurrence of SDH (in the presence or absence of subarachnoid haemorrhage) and RH (alone or in combination)?

The following mechanisms and circumstances are discussed below:

- •

shaking in the absence of an impact;

- •

mild HI by fall from a low height;

- •

playing;

- •

childbirth;

- •

hypoxia or anoxia;

- •

resuscitation manoeuvres.

1.4.1.1

Shaking in the absence of an impact

1.4.1.1.1

Subdural haematoma

Biomechanical evidence.– In their first study in 1987, Duhaime et al. estimated that shaking in the absence of an impact could not cause brain lesions or SDH. However, the reference values used in the study had been obtained in primates and the transposition to infants had not been validated.

Some more recent biomechanical studies have indicated that shaking in the absence of an impact is sufficient to rupture the corticodural veins. Roth et al. , by using a finite element model of the infant head to show that even though the pressure and shearing values are significantly higher in cases of impact, the relative extension of the corticodural veins is similar in the presence and absence of impact (180%) and exceeds the degree of stretching need to rupture the said veins in children under 3 months of age (150%) .

Clinical evidence.– Several clinical studies have confirmed that SDH may be caused by shaking in the absence of an impact . Moreover, SDH are more frequent in confirmed cases of AHI by shaking than in accidental HI in children of the same age .

Autopsy data.– Autopsy data confirm also the existence of SDH in the absence of any signs of external impact .

In conclusion.– There are sufficiently clinical, radiological, autopsy and biomechanical arguments to affirm that SDH can occur with shaking in the absence of any impact.

1.4.1.1.2

Retinal haemorrhage

Shaking in the absence of an impact can cause RH. In fact, RHs seem more strongly linked to the mechanism of shaking than to the occurrence of an impact.

Biomechanical elements.– Modelling of the infant eye has shown that during shaking, significant stress is applied to the posterior pole as a result of the strong traction exerted by the optic nerve on the retina. This explains the predominance of lesions to the posterior part of the retina .

Clinical elements.– RHs are found in cases of SBS both with and without cranial impacts and may be even more frequent during shaking alone (in the absence of an evidenced impact) .

Further evidence in favour of a link between the shearing mechanism and RH is the fact that in cases of AHI (compared with accidental HI), RH are:

- •

more frequent: 80%, on average (ranging from 50 to 100%, depending on the study) in cases of shaking vs. 8.9% on average for all the cases in the literature on road accidents collated by Kivlin et al. ;

- •

bilateral in the great majority of cases (83 to 90%) ;

- •

often more abundant ;

- •

more abundant in cases of certain SBS than in cases of probable SBS ( P < 0.0001) .

Type 3 RH extending out to the periphery are extremely rare after accidental HI:

- •

they are extremely rare in road accidents ;

- •

they have been reported only five times in other circumstances that were not simple falls (a television set or a 63 kg person falling on the child’s head; a child falling off a platform in a play area ), some of which are controversial because there were no independent eye witnesses, no autopsy data and no fundoscopy data from an ophthalmologist .

According to Betz et al. , massive RH covering more than 20 to 30% of the whole retina’s surface area cannot be explained by a simple, accidental HI and a banal fall in particular. According to Defoort-Dhellemmes , type 3 RH are considered as almost pathognomonic for shaking .

In conclusion.– Type 3 RH (but also types 1 and 2 RH) can occur during shaking in the absence of an impact and seem even more related to the mechanism of shaking than to the existence of an impact.

Type 3 RH are extremely rare in other circumstances and are thus almost pathognomonic for shaking.

1.4.1.2

Mild head injury: falls from a low height

In the absence of a formal definition of “mild” injury, examples of trauma considered to be mild (falls from a low height, in particular) and for which some evidence exists in the scientific literature have been extrapolated.

1.4.1.2.1

Falls are the main explanation given by adults

It is particularly important to study the mechanism of falls because the latter explanation is that most frequently alleged by adults to justify the lesions observed in an infant .

It is probably often accepted in error in the absence of other plausible explanations, as very strongly suggested by several studies:

- •

in 1991, Chadwick et al. reviewed the medical records of 317 consecutive admissions to a children’s trauma centre in San Diego between 1984 and 1988, for which a history of a fall was reported by the parents as being the cause of HI. The researchers analysed the data on the history as reported and did not evaluate their probability or credibility with respect to the diagnosis and the outcome. For the 283 children for whom the height of the fall was known, they found 7% of deaths for falls reportedly from a height of less than 1 metre (7 out of 100), compared with a rate mortality of 0% for falls from a height of between 1 and 3 m (0 out of 65) and of 0.8% for falls from a height of between 3 and 12 m (1 out of 118). The age of the child was not always specified but of the seven deaths for alleged falls from a height of less than 1 metre, two children had fallen from their own height (and thus were under the age of four because a 4-year-old is 1 metre tall, on average), two had fallen from a bed or a table (which suggests a young age) and two children (aged 6 weeks and 13 months) had fallen from someone’s arms. Lastly, the remaining case (an 11-month-old child) had fallen down the stairs;

- •

in a prospective study of 398 falls by children admitted to Oakland Children’s Hospital over a 2-year period, Williams compared two populations of under-3s for whom the alleged causal mechanism was either a fall reported by family members or carers (53 cases) or by a neutral eye witness or several eye witnesses (106 cases). The researchers observed a death rate of 3.8% and a serious HI rate of 34% for cases with related eye witnesses and no deaths (other than a child who fell 21 m) and no serious HIs for cases with neutral or several eye witnesses;

- •

in an editorial , Chadwick insisted on the fact that reliably witnessed cases in mechanistic studies are those occurring in hospital or an authorized care setting under certain conditions. He considered that cases for which the eye witnesses are carers or other children should not be included in databases concerning alleged mechanisms.

1.4.1.2.2

Mortality due to falls from a low height

In the child under 5 years of age, the immediate or differed mortality rate after a fall from a low height (< 1.5 m) is very low:

- •

on the basis of a review of three databases in the United States, five book chapters, the work of two learned societies, seven literature reviews and 177 articles published in peer-reviewed journals, Chadwick et al. estimated the mortality rate at less than 0.48 per million under-5s per year (some cases were included in this study despite doubtful circumstances of occurrence). The estimation of the incidence under the age of 1 year was not specified;

- •

in five studies, none of the 708 children who fell in a hospital setting (at least 94 of whom were under the age of one) died .

Denton and Mileusnic published the case of a 9-month-old child (looked after by its grandmother) who died 72 hours after a backwards fall from a 76-cm-high bed where it was sitting. The child (which did not have any clinical symptoms until the evening before death) was found dead in the morning. The autopsy evidenced mild parenchymatous brain lesions and slight SDH above a linear parietal fracture, without disjunction of the edges in spite of massive brain oedema (1035 g for an expected weight of 750 g). There were no RHs. However, this case (not considered by Chadwick et al. as resulting from a fall from a low height) cannot be taken into account since (i) the eye witness was not neutral and (ii) the absence of disjunction of the sutures (despite a large oedema) argues in favour of a very recent HI – which casts doubt on the alleged mechanism of a fall from a low height.

The article by Plunkett on 75,000 playground accident reports over a period of 11.5 years showed that death is possible but extremely rare after a fall from a low height. Eighteen children (0.024%) aged from 12 months to 13 years had died “following a fall from playground equipment from a height of between 0.6 to 3 m” (the height was judged in terms of the part of the body nearest to the ground at the time of the fall, rather than the distance above ground of the child’s centre of gravity). However, the following points must be noted for the eight deaths of children aged three or under (cases 1 to 8):

- •

none of the children was under 1 year of age and the four youngest cases (cases 1 to 4) were 12 to 20 months old;

- •

the eye witnesses were either family members in five of the eight cases (cases 1 to 4 and 6). This was particularly the case for the four youngest children and one other child (case 8);

- •

an autopsy was not performed in three cases (cases 1, 2 and 7). In a fourth case (case 4), the autopsy was “limited”;

- •

only one of the four youngest children received a full autopsy (case 3);

- •

being swung or rocked was associated with the fall in three of the eight cases (cases 1, 3 and 6), including two of the four youngest children;

- •

the lucid interval between the fall and the first symptoms was always less than 15 minutes and was even zero in three cases (cases 1, 3 and 6);

- •

brain oedema was indicated as the cause of death – even for cases lacking an autopsy.

In the eight youngest children in this series, only case 5 (a 23-month-old child having fallen over a barrier around a platform situated 0.7 m above the ground) appears to be an incontestable HI due to a fall from a low height (a filmed case, with an autopsy). There was a 10-minute lucid interval before coma. The lesions observed before death were:

- •

bilateral RH evidenced 24 hours after admission but with no other details (the fundoscopy was not performed by an ophthalmologist) and not described later at autopsy either;

- •

a large right SDH with disappearance of the lateral ventricle and mild subfalcine herniation on the initial CT scan. Soft tissues were not studied. The SDH had been evacuated.

At autopsy, the following were found:

- •

a right frontal impact;

- •

a small residual SDH;

- •

a right parietal parenchymatous contusion;

- •

brain oedema with cerebellar herniation.

The low risk of death by falling from a low height is emphasized by the fact that even falls from a great height have a very low mortality rate:

- •

two studies found no deaths for falls from heights of less than three storeys:

- ∘

Smith et al. : a study on falls from three storeys or less by 70 children aged from 10 months to 15 years (50% of whom were under 3 years of age),

- ∘

Barlow et al. : 61 children under 16 years of age;

- ∘

- •

in the series by Chadwick et al. , only one of the 118 children admitted after a fall from more than 3 m died (it was 11 months old). None of the 65 children having fallen from 1 to 3 m died.

1.4.1.2.3

Which clinical signs result from falls from a low height?

A few studies provide reliable data falls from a low height (corresponding to a mild HI) that have occurred in well-established circumstances (as observed by objective or several eye witnesses):

- •

five studies concerning falls of hospitalized children found the same results: no deaths and one case with vigilance disorders (a neonate having fallen 1 m off a delivery table) among 708 children in total, including 493 children under the age of seven. On the basis of the details given by the articles, one can establish that at least 94 of the children were under the age of one ;

- •

a prospective study of 106 children under 3 years of age with neutral eye witnesses did not find any serious clinical manifestations (bruising, abrasions, cuts or neurological disorders) and found only three skull fractures without loss of consciousness (a fall against a hard edge) for falls from a height of less than 1.5 m;

- •

other data came from questionnaires put to parents on possible previous falls and consequences. Kravitz et al. questioned the mothers of children under 1 year of age ( n = 536) and established that over half of these children had fallen from a low height at some moment in their life, with very few serious injuries and no fatalities . Fifteen children had been hospitalized. The reported symptoms were lethargy in 14 cases, a loss of consciousness in two cases, vomiting in eight cases and convulsions in two cases. The total number of consultations has not been indicated;

- •

of 3357 falls (including 97% concerning the head) in 2554 children monitored longitudinally from birth to the age of 6 months, an injury was reported in 437 cases (as bruising in 244 cases and as a fracture or mild HI [commotion] in less than 1% of cases [21 times]) .

On the basis of these studies, it is clear that a fall from a height of 1.5 m hardly ever leads to death (fewer than 0.48 per million under-5s per year ) and rarely produces clinical signs.

1.4.1.2.4

Can subdural haematomas be observed after falls from a low height?

Available data.– A few articles are available:

- •

on the basis of two studies of infant death [first study: 63 accidental deaths, including 10 by accidental HI and six by falls, excluding deaths due to drowning, fires, burns and road accidents, with 25 (39%) children under 1 year of age, 18 (28%) between 1 and 2 years of age and five (8%) between 2 and 3 years of age; second study: 21 accidental deaths, including two due to HI and with nine children (43%) under 1 year of age] performed in a city with two million inhabitants over a 24-year period (1975 to 1985 and 1986 to 1999) and other studies in the literature, Case concluded that in cases of falls from a height of less than 1.8 m (6 feet), fractures of the skull were observed in 1 to 3% of cases. The factures are generally linear and are not accompanied by intracranial haemorrhage or neurological impairments. Fewer than 1% of these fractures caused EDH (1–3 per 10,000) and even fewer caused a contact subdural haemorrhage. When these haemorrhages are sufficiently voluminous to create a mass effect, death can occur by intracranial hypertension. In all these cases, the EDH and SDH were focal and were situated at or adjacent to the fracture;

- •

based on his experience and a literature review, Dias found that:

- ∘

falls from a height of less than 1.5 m (5 feet) can cause intracranial damage, albeit very rarely (usually skull fractures, EDH and subarachnoid haemorrhage but also localised SDH),

- ∘

diffuse SDH and brain hypodensities “are extraordinarily rare if they exist at all” (Dias did not find any case reports),

- ∘

the lesions are often silent or poorly symptomatic and do not leave sequelae,

- ∘

falls from a low height are even less likely to be lethal. Sixty-seven to 75% of the deaths were due to lesions with a mass effect (EDH, SDH);

- ∘

- •

Matschke et al. found just one case of SDH due to accidental HI (a road accident) in a study of 715 consecutive autopsies of children under 1 year of age [with deaths due to malformation (almost 300), perinatal complications (175 cases), infections (under 100 cases) and metabolic damage (30 cases)]. The SDH was localized.

Biomechanical aspects.– Bertocci et al. have studied linear accelerations of the head for falls from the height of a bed onto different types of surfaces. Even though further research is still necessary to determine the lesional limits of the child (since the values obtained [55 to 418 m/s 2 ] are very much lower than the lesional threshold in the adult [900 m/s 2 ]), the work suggests that (for the falls studied) serious brain lesions (such as acute SDH or intracerebral haemorrhage) cannot occur, since the linear acceleration is too low.

Conclusions concerning SDHs.– SDH after falls from a low height are extremely rare and are localised. They are mostly adjacent to the fracture line. Given the extreme rarity of this situation, the observation of SDH after an alleged fall from a low height should prompt the healthcare professional to first consider AHI as the cause.

1.4.1.2.5

Retinal haemorrhage after a fall from a low height

Regardless of the height of the fall, RHs are rarely described in falls with one or more neutral, reliable eye witnesses.

After a fall from a low height, RHs (when observed) are never widespread in terms of either surface area or depth, as described in cases of AHI. The RHs are then more likely to be associated with an EDH and are moderate: small intraretinal or preretinal haemorrhages, situated on the posterior pole of the eye . They are usually unilateral but can be bilateral and often asymmetric (in the series reported by Defoort-Dhellemmes ).

1.4.1.2.6

Subdural haematoma and retinal haemorrhages after a fall from a low height

Christian et al. have reported three cases of traumatic SDH occurring at home, including two cases with RHs that were limited to the posterior pole (with pre-, intra- or subretinal haemorrhage) in one eye only. However, none of these cases corresponded to a fall from a low height:

- •

a fall down 13 steps by a 13-month-old child, with local signs of impact (skin contusions on the forehead, nose abrasion) and RH on the same side as the SDH;

- •

a fall through banisters onto a concrete floor by a 7-month-old child, with a skull fracture and right-side brain parenchymatous contusion but no RH;

- •

a fall suffered by a 9-month-old infant after being swung: it was stated that the father lost his grip while swinging the child in his arms. The rear of the child’s head had then hit the ground. This case cannot be considered as an example of a fall from a low height because:

- ∘

the eye witness (a family friend) was not neutral,

- ∘

the combination of swinging and a loss of grip during swinging cannot be likened to a simple fall from a low height,

- ∘

the height was very low (30 cm),

- ∘

there was no lucid interval,

- ∘

in contrast to the significant internal lesions (parieto-occipital SDH and RH), there were no external lesions, bruising or soft tissue damage observed in the other two cases to suggest an impact.

- ∘

Vinchon et al. gathered 3 years of prospective data on 150 under-2s having suffered an HI. Seventy-three cases were considered to be accidental. There were 12 road accidents. The trauma occurred at home in 55 cases and was been reported as a fall in 53 of these: 13 falls from a seat, 10 down the stairs, nine from the arms of an adult, nine from a table, eight falls when standing or from a great height and two from a bed. The eye witness (when there was one) was a family member or friend in all cases. In some cases, the traumatic nature of the incident has been deduced from the observed lesions. RHs were observed in five of the 73 children but Vinchon et al. did not state which children were concerned, how old they were and what the associated intracranial lesions were. On the basis of this article, it is impossible to identify any case of a child with both SDH and RH after a fall from a low height (especially in the absence of any neutral eye witnesses).

For the four cases of children aged between 12 to 20 months of age who died after playground accidents described by Plunkett , only one (case 4) had undergone fundoscopy and presented SDH and bilateral RH (RH in several layers). The fundoscopy had not been performed by an ophthalmologist. The eye witness was not neutral.

In summary, there are no literature cases of children under the age of one presenting both SDH and RH after a fall from a low height.

1.4.1.3

Can shaking be performed by another child?

There is only one biomechanical study on this subject . Morison asked some children aged from 3 to 15 years of age to shake masses corresponding to infants weighing 3 to 10 kg. The children under four were unable to shake 3 kg weights, those under six were unable to shake 5 kg weights, those under nine were unable to shake 7 kg weights (which corresponds to the weight of a 6-month-old child) and those under 13 were unable to shake 10 kg weights (which corresponds to the weight of a 1-year-old child). The acceleration of the shaking (when the latter was possible) was well below that generated by an adult: for example, for a 7 kg weight (corresponding to the weight of a 6-month-old child), the acceleration was estimated to be 2125 cm/s 2 , whereas shaking by an adult produces almost twice as much (3954 cm/s 2 ).

1.4.1.4

Activities considered to be play by the family or carers

Very few studies have addressed this question.

1.4.1.4.1

Biomechanical aspects

Adults sometimes mention a mechanism that involves shaking the infant in “baby bouncer” seat by an older child.

Jones et al. studied a manikin corresponding to a 5-week-old child and submitted it to rocking in a “baby bouncer” seat. The acceleration values ranged from 6 to 16 G (compared with the 50 G peak acceleration considered to be lesional, 750 G resulting from an impact against a wall and 177 G corresponding to violent shaking). Moreover, when the duration of action is taken into account, the resulting index ranged from 2 to 52 (in comparison with a value of 1000 for a 50% chance of severe neurological damage in an adult). Even though if further studies are necessary to determine the lesional limits in the child, the values obtained (2 to 52) are well below the lesional threshold in the adult (1000) and suggest that it is very likely that serious brain lesions cannot occur through shaking in a “baby bouncer” seat.

1.4.1.4.2

Clinical aspects

There are no literature reports or expert feedback on any cases of HI with RH or SDH having occurred during play.

1.4.1.5

Childbirth

Childbirth is sometimes suggested as being responsible for SDH or RH. Hence, the lesions that can be observed after childbirth and their change over time in an asymptomatic child are specified below.

1.4.1.5.1

Subdural haematoma

Biomechanical elements.– The subdural lesions occurring during childbirth correspond to “static” compression phenomena, rather than impacts.

Clinical aspects.– The type of delivery influences the frequency of occurrence of intracranial haemorrhage, which occurs above all in cases of abnormal labour. Towner et al. studied 583,340 consecutive live, first births of children weighing 2500 to 4000 g (excluding multiple pregnancies) registered in a Californian database between 1992 and 1994, and examined the relationship between morbidity and the type of delivery. The rate of intracranial haemorrhages is higher after vacuum-assisted delivery, force forceps delivery and caesarean section performed after induction of labour than for non-instrumented delivery or caesarean section performed before induction of labour. This suggests that the risk is above all related to an abnormal course of labour.

We reviewed prospective studies on asymptomatic children . None of these children had undergone fundoscopy.

Asymptomatic SDH can be seen soon after childbirth (within 72 h), with a variable frequency of 9 to 46% depending on the investigational technique (ultrasound vs. MRI), the MRI field strength and the use of coronal slice to differentiate between supratentorial and subtentorial locations, the date of the examination and the type of delivery.

SDH is found more frequently when investigated soon after birth, with a more powerful MRI system, after vaginal delivery (14 to 33%), for vacuum-assisted delivery (40 to 77%) or forceps delivery (30 to 33%), for higher birth weights , lesions in the genital area , premature deliveries (24% in the study by Sezen ) and for first children (20% in the study by Sezen ).

These SDHs are situated on the subtentorial level, the supratentorial level or both. Whitby et al. and Looney et al. described a preponderance of subtentorial sites – in contrast to Rooks et al. .

Supratentorial SDH can be occipital but also parietal or temporal. In the series reported by Rooks et al. , all 46 cases of supratentorial SDH were situated in the posterior half of the skull: 30 out of 46 (65%) were interhemispheric and posterior, 29 out of 46 (63%) were occipital and 22 out of 46 (22%) were close to the tentorium cerebelli. Twenty children (43%) had also SDH of the posterior fossa. None of the cases of asymptomatic, supratentorial SDH in the series was frontal, as also reported by Whitby et al. . In the series reported by Rooks et al., 74% of the cases (34 out of 46) had SDH in two or three areas. The SDH was always homogeneous in all the MRI sequences . In the study by Looney et al. (using a 3 Tesla MRI machine), the 12 cases of multiple SDH were homogeneous and the lesions had the same age. The haemorrhage was often mild and appeared in the form of a thin film. None of the 46 cases described by Rooks et al. had an extradural subarachnoid or intraparenchymatous haemorrhage.

In summary, in the context of childbirth, SDH can be evidenced by brain imaging in asymptomatic neonates. The SDH is generally situated generally in a supratentorial site in the posterior half of the skull (not the anterior half) or in the posterior fossa – sites which are found in SBS. These SDHs are often multifocal. They are homogeneous and have the same age (when this information is given).

In the referenced studies, the follow-up data (when complete) showed that these asymptomatic SDHs did not progress to chronic SDH and resolved spontaneously within 1 month , except for one case in Rooks et al. which initially had (i) bilateral occipital SDH and (ii) SDH of the posterior fossa and then developed (at 26 days of age) a new left-side, frontal SDH. An examination at 5 months confirmed the disappearance of the SDH but enlargement of the pericerebral spaces.

1.4.1.5.2

Retinal haemorrhage

On the basis of several prospective studies, it seems that about one in three term neonates have RHs. They are found after all types of childbirth but occur more frequently after forceps or (even more so) vacuum-assisted deliveries. These haemorrhages are almost always superficial and deep intraretinal and uni- or bilateral (52%, i.e. 26 out of 50 of the cases reported by Emerson). They are often numerous (> 10) and extend out to the periphery in a third of cases. In 15 to 25% of cases, the RH has a white centre. They disappear very rapidly – often in less than 3 days . The RHs are very rarely still found at 1 month of age (two out of 202 cases, both of which involved vacuum-assisted delivery) and are never found after 2 months .

In summary, in a context of childbirth (particularly after forceps and vacuum-assisted deliveries) in asymptomatic neonates, RH of various types exist in a third of cases. These are mainly Defoort-Dhellemmes type 1 or 2 and disappear in less than a month (and mostly within a few days).

RH and even haemorrhages of the vitreous matter can also occur as a complication of prematurity-associated retinopathy in 1 to 2% of premature infants and can last for longer.

1.4.1.6

Hypoxia and anoxia

1.4.1.6.1

Subdural haematoma

Radiological aspects.– Three retrospective studies on the radiological signs of serious hypoxia have shown the absence of SDH in children (including some with prolonged cardiac arrest ).

Autopsy data.– Byard et al. did not evidence any macroscopic SDH in a series of 82 autopsies with histological proof of hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy in children under the age of three, other than in a context of SBS. They did not differentiate between foetuses and neonates.

Matschke et al. (who did not differentiate between foetuses and neonates either) found only 50 macroscopically observable cases of SDH in 715 consecutive autopsies performed in children under 1 year of age, most of whom had suffered from hypoxia before death [malformation (40.4%), the outcome of a perinatal complication (24.3%), infection (12.2%), metabolic disease (4.5%), sudden infant death (3.4%), inflicted trauma (2.4%) and other non-natural causes (2.1%)]. A cause was found for all the cases of SDH when a full dataset was available, i.e. in 48 cases out of 50: 14 cases of SBS, one case of accidental injury, 13 haemostasis disorders, 13 perinatal deaths, four deaths due to metabolic causes, three due to infectious disease and cases of two very localised SDH after sudden death. The most frequent cause was inflicted trauma (14 cases) and the latter mechanism was also mentioned for the two cases with incomplete data.

Thus, SDH in a hypoxic context is extremely rare. This is also what clinical studies show .

Upon histological examination, Geddes et al. found 36 intradural haemorrhages (IDH) in 50 foetuses and children but only one (unilateral) SDH was found macroscopically (in a child born after 25 weeks of pregnancy, who died of an infection after 1 week of life). In the 30 children born alive, only 13 had a histologically manifest IDH. Twelve of the 13 deaths occurred very early in perinatal period (during the first week for 11 of them) or the neonatal period (the first month of life for the 12th case) and only one of the children with clear IDH corresponded to the average age for SBS. Childbirth had been excluded as a possible cause of bleeding in 72% of the cases (36 out of 50: in 11 of the 17 in utero deaths but also in 13 of the 18 children who had lived more than 5 days [median: 23 days]), whereas haemorrhages due to childbirth can last up to 1 month. The difference in the frequency of occurrence of IDH (pooling “+” cases and “++” cases) according to whether there was hypoxia and anoxia or not was not significant ( P = 0.15) but it was stated that this lack of significance was due to the small number of cases. Despite this lack of significance, a “unified hypothesis” was presented. It supposed that subdural bleeding seen in some cases of HI in the child can result from passage of blood from the intracranial veins to the subdural space, due to a combination of severe hypoxia, brain oedema and an elevation in the central venous pressure. According to Geddes et al., subdural bleeding may thus not be due to rupture of the corticodural veins but may testify to immaturity – with no need for an impact or considerable force.

Cohen and Scheimberg evidenced clear IDH and signs of hypoxia of various degrees of severity in 25 foetuses and 30 children who died within the 19 first days of life, including 25 in the first week. SDH was found in two thirds of cases (16 foetuses and 20 neonates). The IDH was predominantly in the posterior part of the falx cerebri and the tentorium cerebelli.

In summary, hypoxia:

- •

is likely, in a particular population constituting of foetuses and children who died in the first month of life (mostly in the first week), to cause, contribute to or be associated with histologically detectable IDH and, at most, very mild posterior supratentorial and subtentorial subdural effusion (a thin film). Intradural suffusions may be missed on imaging or even on autopsy when the sample is inadequate;

- •

does not produce any macroscopic SDH in children over the age of 1 month.

1.4.1.6.2

Retinal haemorrhages

Acute hypoxia (such as that produced during suffocation, which frequently produces petechiae at the surface of the lungs, the heart or other internal organs) does not cause any RH.

1.4.1.7

Resuscitation manoeuvres

At the time of diagnosis of SDH, cardiorespiratory resuscitation manoeuvres are sometimes alleged to have caused bleeding.

1.4.1.7.1

Subdural haematoma

There are no known literature reports of an association between SDH and cardiorespiratory resuscitation.