1

English version

This text is divided into three sections. The first section is devoted to the diagnosis of shaken baby syndrome (revealing signs, risk factors, investigations to be performed, possible lesions, etc.) and ends with suggested diagnostic criteria based on the infant’s clinical history and lesions. The second section looks at whether certain mechanisms, The second section looks at whether other mechanisms (some of which are often cited, such as being dropped often-cited(such as being dropped or the performance of resuscitation manoeuvres) can induce injuries similar to those seen in shaken baby syndrome. It also looks at whether certain factors can favour the occurrence of injuries. The third and last section focuses on the consequences (according to French regulations and legislation) of a diagnosis of shaken baby syndrome.

1.1

Abbreviations

CIVI

commission d’indemnisation des victimes d’infraction pénale (crime victim compensation commission)

CRIP

cellule de recueil, de traitement et d’évaluation des informations préoccupantes (county child abuse prevention office)

ESAS

enlargement of the subarachnoid space

MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

OPP

ordonnance de placement provisoire (temporary care order)

RH

retinal haemorrhage

SBS

shaken baby syndrome

SDH

subdural haematoma

1.2

Participants

This public audition was organized by the French Society for Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (SOFMER), with the participation of the following bodies:

- •

National College of Lecturers in General Practice

- •

INSERM – The French National Institute of Health and Medical Research

- •

InVS – The Health Surveillance Institute

- •

The French Society for Anaesthesia and Resuscitation

- •

The French Society for Emergency Medicine

- •

The French Society for Forensic Medicine

- •

The French Society for Paediatric Neurosurgery

- •

The French Academy of Neuropediatrics

- •

The French Academy of Pediatrics

- •

The National Union of Associations of Families of Victims of Brain Injury (UNAFTC).

1.2.1

Funding

- •

The Provincial Liberal Professions Health Insurance Fund

- •

The General Directorate for Health

- •

France Traumatisme Crânien

- •

The French Society for Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (SOFMER)

- •

The French-Language Society for Paediatric Disability Research (SFERHE)

- •

The Île-de-France Liberal Professions Health Insurance Fund.

1.2.2

Organizing committee

- •

Dr Anne Laurent-Vannier, physical and rehabilitation medicine specialist, Saint-Maurice – Chairperson of the Organizing Committee

- •

Dr Juliette Bloch, epidemiologist, InVS, Saint-Maurice

- •

Thierry Boulouque, Division Commissioner, Head of the Child Protection Unit, Paris

- •

Dr Jeanne Caudron-Lora, emergency physician, Créteil

- •

Professor Brigitte Chabrol, paediatrician, Marseille

- •

Frédéric De Bels, HAS, Saint-Denis, La Plaine

- •

Dr Patrice Dosquet, HAS, Saint-Denis, La Plaine

- •

Françoise Forêt, Honorary Professor, National Union of Associations of Families of Brain Injury Victims (UNAFTC), Paris

- •

Dr Jose Guarnieri, neurosurgeon, Valenciennes

- •

Professor Vincent Gautheron, physical and rehabilitation medicine specialist, Saint-Étienne

- •

Dr Cyril Gitiaux, paediatrician, Paris

- •

Anne-Sophie Jarnevic, magistrate, Chartres

- •

Thérèse Michel, social worker, Tours

- •

Professor Gilles Orliaguet, specialist in anaesthesia and resuscitation, Paris

- •

Dr Claude Rougeron, general practitioner, Anet

- •

Professor Michel Roussey, paediatrician, Rennes

- •

Yvon Tallec, magistrate, Paris

- •

Professor Gilles Tournel, forensic physician, Lille

- •

Dr Anne Tursz, Research Director, INSERM, Villejuif

1.2.3

Hearing Commission

- •

Dr Mireille Nathanson, paediatrician, Bondy – Co-Chairperson of the Hearing Commission

- •

Fabienne Quiriau, Director of the National Convention of Child Protection Associations (CNAPE), Paris – Co-Chairperson of the Hearing Commission

- •

Aurélie Assie, social worker, Paris Child Assistance Unit, Family Reception Service, Ecommoy

- •

Dr Joseph Burstyn, ophthalmologist, Paris

- •

Dr Christine Cans, paediatrician, Grenoble

- •

Dr Catherine Arnaud, paediatrician, Toulouse

- •

Violaine Chabardes, gendarme (police officer), Lyon

- •

Hélène Collignon, journalist, Paris

- •

Dr Marie Desurmont, forensic physician, Lille

- •

Isabelle Gagnaire, childcare nurse, Saint-Étienne

- •

Professor Nadine Girard, radiologist, Marseille

- •

Professor Étienne Javouhey, resuscitation specialist, Lyon

- •

Dr Anne Laurent-Vannier, physical and rehabilitation medicine specialist, Saint-Maurice

- •

Philippe Lemaire, magistrate, Paris

- •

Dr Caroline Mignot, paediatrician, Paris

- •

Philippe Lemaire, magistrate, Riom

- •

Dr Sylviane Peudenier, neuropaediatrician, Brest

- •

Dr Bruno Racle, paediatrician, Versonnex

- •

Dr Pascale Rolland-Santana, general practitioner, Paris

- •

Dr Thomas Roujeau, neurosurgeon, Paris

- •

Dr Nathalie Vabres, paediatrician, Nantes

- •

Roselyne Venot, police officer, Versailles

1.2.4

Literature review coordinators

- •

Dr Elisabeth Briand-Huchet, paediatrician, Clamart

- •

Jon Cook, anthropologist, Villejuif

1.2.5

Experts

- •

Professor Thierry Billette de Villemeur, paediatrician, Paris

- •

Professor Jean Chazal, neurosurgeon, Clermont Ferrand

- •

Professor Catherine Christophe, radiologist, Brussels

- •

Dr Sabine Defoort-Dhellemmes, ophthalmologist, Lille

- •

Dr Gilles Fortin, paediatrician, Montreal

- •

Dr Caroline Rambaud, forensic physician, Garches

- •

Professor Jean-Sébastien Raul, neurosurgeon, Strasbourg

- •

Dr Caroline Rey-Salmon, paediatrician, Paris

- •

François Sottet, magistrate, Paris

- •

Elisabeth Vieux, honorary magistrate, Paris

- •

Professor Mathieu Vinchon, neurosurgeon, Lille

- •

Professor Rémy Willinger, Professor of Biomechanics, Strasbourg

Illustrations supplied by the Société francophone d’imagerie pédiatrique et prénatale (SFIPP).

1.3

Recommendations

1.3.1

Shaken baby syndrome: the diagnostic work-up

SBS is a type of inflicted, non-accidental or abusive head injury caused by shaking (either alone or combined with an impact). It mainly occurs in babies under the age of one.

It is thought that 180 to 200 children per year are victims of this type of abuse in France, although this value is certainly an underestimate. Failure to diagnose SBS increases the likelihood of recurrence.

1.3.1.1

In a baby (alive or dead), which clinical signs are or may be suggestive of a diagnosis of shaken baby syndrome or may lead to misdiagnosis?

1.3.1.1.1

Initial symptoms

The initial symptoms are as follows:

- •

in the most serious cases, “the child is found dead”. In such an event, it is essential to follow the guidelines issued by the French National Authority for Health1 5

5 Management of the unexpected death of a baby (under the age of 2): good practice guidelines. HAS. February 2007.

. In particular, an autopsy is essential. Unless otherwise decided by the State Prosecutor for forensic and legal reasons, performance of an autopsy requires the parents’ consent;

- •

“Serious neurological damage” may be immediately apparent by: severe malaise, impaired vigilance (extending to coma), severe apnoea, convulsions, fixed upward gaze, signs suggesting acute intracranial hypertension and even tentorial herniation;

- •

“Other signs suggestive of neurological damage”: poor contact and a decrease in the child’s capabilities;

- •

“Some non-specific signs of neurological damage” can lead to misdiagnosis: behavioural changes (irritability, changes in sleep or feeding patterns), vomiting, interruption of breathing, paleness and apparent pain.

The clinical examination must be thorough and performed after undressing the child; in particular, it should include palpation of the fontanel, measurement of the head circumference (which should be checked against the growth chart to see whether there has been a change in the percentile class) and examination of the whole body (including the scalp) for bruises.

Given the lack of specificity of certain signs, “a combination of signs” may provide much more information: a combination of vomiting with a bulging fontanel, convulsions, axial hypotonia or vigilance disorders; a combination of convulsions with axial hypotonia or a bulging fontanel; a bulging fontanel with a sharp shift upwards of the head circumference curve.

1.3.1.1.2

Absence of a lucid interval

In most cases (or even in all cases), shaking produces immediate symptoms.

Of course, it must be borne in mind that the consultation may take place some time after shaking has occurred.

1.3.1.1.3

Other elements that can be suggestive of shaking

The other elements are:

- •

data from the medical history and interview:

- ∘

a delay in seeking medical assistance,

- ∘

the lack of an explanation for the symptoms, an explanation that is not compatible with the child’s clinical status or developmental stage or an explanation that changes over time or differs from one person to another,

- ∘

a spontaneous report of a minor head injury that had occurred in the past,

- ∘

prior consultations for crying or any type of injury,

- ∘

a history of unexplained sibling death;

- ∘

- •

risk factors:

- ∘

Boys, premature babies and children from multiple pregnancies are more likely to be shaken,

- ∘

Although the shaker is usually a man living with the mother (who may be the child’s father or the mother’s partner), babysitters or carers are involved in about one case of shaking in five,

- ∘

Although shaking occurs in all socioeconomic, cultural and intellectual settings, it has been noted that: a history of alcoholism, drug abuse or family violence is a risk factor and the shaker often has very poor knowledge of a child’s needs or normal behaviour,

- ∘

The parents are often socially isolated.

1.3.1.1.4

Should the child be hospitalized?

If the physician suspects a diagnosis of SBS, he/she must tell the parents about his/her concern for the child’s status and inform them that emergency hospitalization is indicated.

1.3.1.2

What type of lesions occur and what clinical and paraclinical assessments are necessary and sufficient to detect them?

1.3.1.2.1

Lesions observed in shaken baby syndrome

In SBS, the meninges, brain, eyes and spinal cord are likely to be damaged. Other lesions may also be present: injury to the neck and cervical spine, limb, rib and/or skull fractures and bruising and haematomas in the teguments and/or neck muscles:

- •

intracranial lesions:

- ∘

SDH:

- –

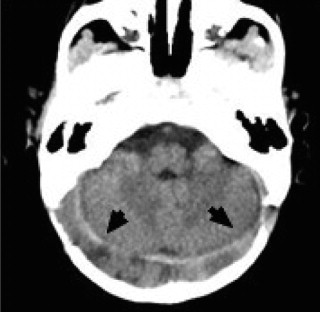

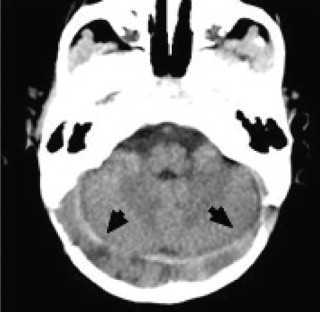

SDH is generally multifocal ( Figs. 1–3 ). and may be accompanied by subarachnoid haemorrhages,

- –

However, it can also be localized,

- –

haemorrhage of the falx cerebri or posterior fossa is very suggestive of SBS,

- –

SDH is not always present in SBS;

- –

- ∘

brain injury: this may be anoxic, oedematous or contusion-like.

- ∘

- •

RH:

- ∘

multiple RH are almost pathognomonic for SBS when profuse or flecked across the retina up to the periphery, with haemorrhagic retinoschisis or a perimacular retinal fold in some cases (type 3 RH, Table 1 ),

- ∘

however, other types of RH can be seen,

- ∘

RH are absent in about 20% of cases of SBS. They are therefore not essential for a diagnosis of SBS but, when present, are strongly suggestive of shaking;

- ∘

- •

skin lesions: in the absence of medical causes, bruising in a child that cannot walk unaided is very suggestive of abuse;

- •

bone injury: bone injuries are suggestive of abuse (particularly rib fractures, signs of costal callus formation, metaphyseal fractures and periosteal spurs;

- •

damage to neck muscles, the spine or the spinal cord.

| Type 1 | Intraretinal haemorrhage, flame-shaped, blot or punctiform, situated at the posterior pole of the eye |

| Type 2 | Small, dome-shaped, preretinal haemorrhages located at the posterior pole of the eye, around the papilla and along the vascular arcades or nearby. Type 2 RH may occur alone or in combination with type I RH |

| Type 3 | Multiple, profuse haemorrhages of all types (intra-, pre- or subretinal haemorrhages) across the whole retina or splattered out to the periphery, combined with premacular haemorrhagic cysts, in one or both eyes |

1.3.1.2.2

Clinical and paraclinical examinations in a living child

This part is as follows:

- •

clinical examination: a thorough examination, particularly the head circumference curve, screening for traumatic injuries (which must be photographed, if found), the state of the fontanel and a neurological examination;

- •

brain CT: the first-line examination. It reveals haemorrhagic lesions and cerebral oedema. In the event of doubt and if the initial result is normal, the CT scan can be repeated 12 or 24 hours later;

- •

ophthalmological examination after dilatation: this must be performed by an experienced ophthalmologist within 48 to 72 hours, at the latest;

- •

MRI: this examination should be performed as soon as the child’s state has stabilized. It is of significant diagnostic value in the acute phase and gives a complete overview of axial and extra-axial lesions (whether haemorrhagic or not). It also probes the brain stem, the spinal cord and the neck region. This forms part of the lesion screening that must be performed before the child is discharged from hospital;

- •

other required examinations:

- ∘

a complete blood count, PT, APTT, coagulation factors,

- ∘

X-rays of the whole skeleton, performed according to the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines 6

6 A skeletal survey is mandatory in all cases of suspected physical abuse in children younger than 2 years (not a “whole body” X-ray): radiographies of the axial skeleton (anteroposterior and lateral views of the thorax, and possibly an oblique view to see the ribs, the upper dorsal and lumbar spine; anteroposterior and lateral views of the pelvis, in order to see the medial lumbar spine; a lateral view of the lumbosacral spine, anteroposterior and lateral views of the cervical spine, anteroposterior and lateral views of the skull [and other views, if necessary]) and all limb segments.

,

- ∘

bone scintigraphy can show evidence of bone lesions that are not apparent on X-rays.

1.3.1.3

Differential diagnoses for shaken baby syndrome

The main differential diagnosis is accidental head injury.

Some rarer medical diagnoses also need to be ruled out:

- •

congenital or acquired disorders of haemostasis (thrombopenia).

- •

cerebral arteriovenous malformations are extremely rare below the age of 1.

- •

metabolic diseases (very rare):

- ∘

glutaric aciduria: diagnosed using chromatographic analysis of urinary organic acids,

- ∘

menkes disease: diagnosis according to the results of serum copper and ceruloplasmin assays.

Although osteogenesis imperfecta is sometimes cited as a differential diagnosis, the overall clinical picture is very different and a causal relationship with the presence of SDH has never been established.

1.3.1.4

Medical criteria enabling a diagnosis of non-accidental head injury (and more precisely, shaken baby syndrome) in a child younger than one year, once differential diagnoses have been ruled out.

1.3.1.4.1

Action to be taken, depending on the clinical situation

Actions to be taken are:

- •

a dead child: autopsy (requiring the parents’ consent) is recommended for all unexpected infant deaths – especially when non-accidental head injury is suspected. The physician must report the case to the State Prosecutor, who may order a forensic autopsy;

- •

early, acute neurological distress: a brain CT scan in the emergency unit, in order to screen for intracranial haemorrhage and other signs;

- •

signs that point towards neurological damage and certain non-specific signs (vomiting, respiratory disorders, paleness, apparent pain):

- ∘

palpation of the fontanel and measurement of head circumference,

- ∘

note whether several signs are present,

- ∘

look for other signs of abuse,

- ∘

any description of a shaking-like act.

It is essential to consider shaking and perform a comprehensive examination, including a brain CT scan and fundoscopy.

When confronted with the slightest suspicion of SBS, the physician must tell the parents about his/her concern for the child’s safety and inform them that emergency hospitalization is required.

High diagnostic value is given to:

- •

a history that is absent, incoherent, changes over time or is incompatible with the observed lesions or the child’s age;

- •

multifocal SDH ( Figs. 1–3 ), particularly at the falx cerebri or posterior fossa;

- •

RH that are profuse or blot the retina out to the periphery, with dome-shaped or plaque-shaped haemorrhages or to a perimacular retinal fold.

1.3.1.4.2

Diagnostic criteria as a function of the observed lesions

In a child under one, after differential diagnoses have been ruled out, a diagnosis of head injury inflicted by shaking is:

- •

highly probable (or even certain) if all the following are present:

- ∘

Multifocal extra-axial haemorrhage: SDH ( Figs. 1–3 ), subarachnoid haemorrhage,

- ∘

AND RH profuse or flecked across the retina out to its periphery,

- ∘

AND a history that is absent, incoherent, changes over time or is incompatible with the observed lesions or the child’s age.

The coexistence of the three above diagnostic elements should prompt a diagnosis of inflicted head injury (probably by shaking);

- ∘

- •

possibly accompanied by:

- ∘

hypoxic brain lesions,

- ∘

cervical lesions (spinal cord haematoma, medullary damage and lesions to the occipitovertebral or cervicodorsal junctions),

- ∘

description of violent shaking by an eyewitness.

- ∘

- •

a diagnosis of head injury inflicted by shaking is probable if:

- ∘

multifocal extra-axial haemorrhage ( Figs. 1–3 ), “with or without” any type of RH,

- ∘

OR localized, extra-axial haemorrhage with type 2 or 3 RH,

- ∘

AND a history that is absent, incoherent, changes over time or is incompatible with the observed lesions or the child’s age;

- ∘

- •

in the event of localized SDH and RH limited to the posterior pole (type 1), with a clinical history that is absent, incoherent, changes over time or is incompatible with the observed lesions or the child’s age, “there was no consensus within the Hearing Commission as to whether the diagnosis of shaking must be considered as «probable» or «possible»”;

- •

a diagnosis of head injury inflicted by shaking is possible if both the following are present:

- ∘

localized SDH,

- ∘

AND a history that is absent, incoherent, changes over time or is incompatible with the observed lesions or the child’s age;

- ∘

- •

the diagnosis of shaking can be ruled out when there is:

- ∘

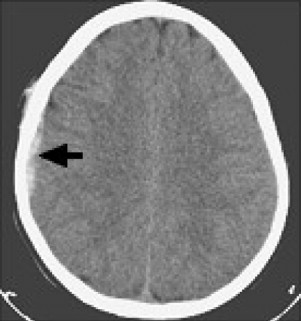

localized SDH ( Fig. 4 ), with a potentially linear fracture and adjacent bruising,

- ∘

AND an unvarying clinical description that is compatible with the lesions and the child’s age and describes a violent, accidental head injury.

1.4

The causal mechanism for lesions

Since the lesions observed in SBS are not highly specific (even though some are highly suggestive), it is important to determine, which lesions can be produced by the acts and incidents frequently mentioned by an adult when a child is taken to hospital after denied shaking. The most frequent explanations are falls and attempts to resuscitate the infant after loss of consciousness. Indeed, some people consider that shaking alone is not sufficient to create lesions and that an accompanying impact is essential. This is why the following question is dealt with here, with a view to facilitating the diagnosis of SBS: which mechanisms or circumstances may be involved in the occurrence of SDH (in the presence or absence of subarachnoid haemorrhage) and RH (alone or in combination)?

The following mechanisms and circumstances are discussed below:

- •

shaking in the absence of an impact;

- •

mild head injury caused by a fall from a low height;

- •

playing;

- •

childbirth;

- •

hypoxia or anoxia;

- •

resuscitation manoeuvres;

1.4.1.1

Shaking in the absence of an impact

This is discussed below:

- •

SDH: SDH can occur during shaking in the absence of an impact. The occurrence of SDH (in even the very youngest children) is more strongly associated with the act of shaking than the existence of an impact;

- •

RH: all types of RH (type 3 but also types 1 and 2) can occur during shaking in the absence of an impact. RH appear to be more strongly associated with the act of shaking than the existence of an impact. Type 3 RH (which are very rare under other circumstances) are almost pathognomonic for SBS.

1.4.1.2

Mild head injury by falling from a low height

It is particularly important to assess the mechanism of falls from a low height, since this is the main explanation given by adults to justify the symptoms observed in an infant:

- •

mortality: the rate of immediate or delayed mortality after a fall from a low height (less than 1.5 m) is very low and has been estimated at no more than 0.48 per million under-fives per year. The low risk of mortality by falling from a low height is emphasized by the fact that even falls from a great height have a very low mortality rate;

- •

clinical signs: a fall from a low height does not cause any major clinical symptoms in most cases: less than half the children have bruising and sometimes a simple skull fracture, with no sequelae;

- •

SDH:

- ∘

on the clinical level, a fall from a low height extremely rarely gives rise to SDH. If present, the SDH is localized and under a fracture line,

- ∘

in biomechanical terms, and even though further studies are needed to determine damage thresholds in children (which are not yet known), convergent results (with values well below the damage thresholds for adults) show that severe brain damage is very unlikely to result from this type of fall;

- ∘

- •

RH: a fall from a low height may very occasionally cause RH. When the latter do occur, they are:

- ∘

never extensive in terms of surface area (they are localized in the posterior pole of the eye) or depth,

- ∘

generally unilateral,

- ∘

generally associated with extradural haematoma but not SDH;

- ∘

- •

SDH + RH: There are no literature reports of a child under the age of 1 with a combination of SDH and RH after a fall from a low height.

1.4.1.3

Shaking by a child

The only literature results concerning this mechanism relate to biomechanical data. Children under the age of 9 are unable to shake masses of 7 kg (the weight of a 6-month-old baby). Furthermore, when older children shake babies, the acceleration involved is roughly half that generated by an adult.

1.4.1.4

Activities considered to be “play” by the carers

Adults sometimes mention a mechanism that involves playful use of a “baby bouncer” seat:

- •

biomechanics: The acceleration generated by rocking an infant in a “baby bouncer” chair is not intense enough to cause lesions;

- •

clinical data: No cases of traumatic head/brain injury with RH or SDH resulting from “play” of this type were found in the literature, nor in the experience of the experts.

There are no literature data on other activities considered to be play.

1.4.1.5

Childbirth

Childbirth is sometimes suggested as being responsible for SDH or RH. Hence, the lesions that may be observed after childbirth and their change over time in an asymptomatic child are usefully specified below.

Subdural lesions occurring during childbirth are not related to an impact but correspond to “static” compression:

- •

SDH:

- ∘

asymptomatic SDH may be seen soon (< 72 h) after birth. The frequency varies from 9 to 46%, depending on the imaging technique, the time interval between birth and the examination and the type and circumstances of the delivery,

- ∘

the incidence of intracranial haemorrhage is greater after vacuum-assisted delivery, forceps delivery and caesarean section performed after induction of labour than for non-instrumented delivery or caesarean section performed before induction of labour,

- ∘

in studies of asymptomatic neonates (who had not undergone fundoscopy), SDH may be seen on brain imaging. They are generally situated in a supratentorial location in the posterior half of the skull (and not in the anterior half) or in the posterior fossa – sites that are found in inflicted head injury. These SDH are often multifocal. When described, the lesions are homogeneous and appear to have arisen at the same time. The SDH resolved spontaneously within a month or less.

- ∘

- •

RH: particularly after the use of a vacuum-assist device or forceps, RH of all types (but mainly types 1 or 2) can be observed in a third of asymptomatic neonates. The RH disappear within a month (usually within a few days),

- •

RH + SDH: no data are available.

1.4.1.6

Hypoxia and anoxia

This is as follows:

- •

SDH:

- ∘

by using imaging techniques, three retrospective studies have demonstrated the absence of SDH in children with serious hypoxia, including children with prolonged cardiac arrest,

- ∘

post-mortem studies: whereas the death of children under the age of 1 is frequently related to severe hypoxia, SDH is rarely found at autopsy and, in this type of case, the cause is known.

In a particular population (constituted of foetuses and neonates that die during the first month of life, usually during the first week), hypoxia is likely to cause, contribute to or be associated with histologically detectable haemorrhage and very thin posterior, supratentorial and infratentorial subdural effusion at most. Hypoxia does not induce macroscopic SDH in children older than one month of age.

- ∘

- •

RH: although acute hypoxia (as can occur during suffocation) frequently produces petechiae at the surface of the lungs, heart or other internal organs, it does not induce RH.

1.4.1.7

Resuscitation manoeuvres

Cardiorespiratory resuscitation manoeuvres are sometimes alleged to have caused SDH:

- •

SDH: there are no known literature reports of an association between SDH and cardio-respiratory resuscitation. The intracranial lesions observed following resuscitation are above all related to whatever circumstances had justified the use of resuscitation manoeuvres;

- •

RH: there are few available studies concerning pre-hospital or hospital-based resuscitation by healthcare professionals. RH are very occasionally found in young babies with neither head injury nor haemorrhagic disease and who have received cardiorespiratory resuscitation (even prolonged). In such cases, the RH are punctiform or flame-shaped, localized (sometimes with a white centre) and situated in the posterior pole in one or both eyes.

1.4.1.8

Other circumstances that may be invoked as causing retinal haemorrhages

The other circumstances are:

- •

convulsions extremely rarely give rise to RH;

- •

coughing: no RH was observed in a series of 100 children with a persistent cough;

- •

vomiting: no RH was observed in a series of 100 children with vomiting due to pyloric stenosis.

1.4.2

To what extent can the date of shaking be determined?

Dating is based on a set of clinical, radiological (from repeated examinations, if need be) and, in some cases, pathological data and on interview data.

1.4.2.1

Dating based on a set of clinical symptoms

Several publications have analysed comprehensive accounts of shaking given by the perpetrators or by third parties in contact with the child soon after shaking; they indicate that the symptoms (when present) occur immediately: the child immediately displays unusual behaviour.

1.4.2.2

Dating based on additional tests

1.4.2.2.1

Retinal haemorrhages

It is difficult to date RH.

Intra-RH disappears within a few days. Only their association with scars, the sequelae of preretinal or sub-RH (circular white scars of retinal folds, macular retraction syndrome, zones of pigmentation and retinal atrophy, particularly in macular areas or at the extreme periphery of the retina, and fibroglial scarring) can be considered as demonstrating the coexistence of older and recent lesions.

1.4.2.2.2

Subdural haematoma and subarachnoid haemorrhage

The time range for dating acute SDH is wide (and always more than 10 days, whether on CT or MRI). It is thus difficult to obtain an accurate date by using imaging data.

Furthermore, it must be noted that:

- •

heterogeneous SDH is not specific for a particular mechanism and does not imply repetition;

- •

heterogeneous SDH can reflect new bleeding from the capillaries of a neoformed membrane in the absence of new shaking;

- •

a child may have been the victim of several shaking episodes, with a possible superposition of lesions of differing ages. The presence of several SDH with different density then becomes highly informative.

1.4.2.3

Dating based on pathology laboratory data

Pathology-based dating is relatively accurate but can only be performed comprehensively after autopsy. The accumulation and crosschecking of all the clinical, imaging and pathology data helps to considerably narrow the time window for the occurrence of trauma – sometimes down to a single day or half a day.

SDH must be studied macroscopically and histologically. Dating depends on the appearance of the clot, the dura mater and the meningeal surface. The study of possible brain contusions (and immunohistochemical analysis of macrophages in particular) can help to date the lesions. Another non-specific element that helps to date the stress is the presence or absence of acute thymic involution. Hence, only an autopsy can provide a precise date.

1.4.3

Are some babies predisposed to the occurrence of subdural haematoma?

1.4.3.1

Expansion of the subarachnoid space

The observation of a widening of the pericerebral spaces coexisting with a SDH has given rise to two hypotheses:

1.4.3.1.1

First hypothesis: the observed widening of the pericerebral spaces is part of an expansion of the subarachnoid space (ESAS) – a clinical entity which may predispose the child to subdural haematoma

No data were found in the literature to support the hypothesis whereby ESAS predisposes to SDH in babies.

1.4.3.1.2

Second hypothesis: the observed expansion of the pericerebral space is the consequence of a previously undiagnosed head injury

Two prospective studies suggest that widening of the pericerebral space discovered during the initial phase of head injury corresponds to damage resulting from a previously undiagnosed head injury, rather than from ESAS.

A follow-up study of changes in brain images in a cohort of: young babies with ESAS and shaken babies would very useful in terms of understanding the natural history of these clinical entities.

1.4.3.2

Can subdural haematoma occur during a CSF circulation disorder?

SDH can occur in a context of excessive CSF drainage or severe dehydration and also as a postsurgical complication of an arachnoid cyst. However, these cases correspond to a particular diagnostic context.

1.4.3.3

Osteogenesis imperfecta

On one hand, osteogenesis imperfecta constitutes a differential diagnosis for diaphyseal and not metaphyseal fractures. On the other hand, even though two articles report the occurrence of SDH in babies with osteogenesis imperfecta, no link between the latter and the occurrence of SDH has been established. SDH is not part of the usual set of symptoms of osteogenesis imperfecta.

1.4.3.4

New bleeding after subdural haematoma

The capillaries of a neoformed membrane can bleed anew, regardless of whether the baby has been shaken again or not.

1.5

How does the probable diagnosis affect the actions to be taken?

Two hypotheses can be envisaged:

- •

the diagnosis of SBS is highly probable (even certain) or probable;

- •

the diagnosis of SBS is possible.

A set of practical guidelines is given below.

1.5.1.1

First hypothesis: a diagnosis of shaken baby syndrome is highly probable (even certain) or probable

The child must be protected and his/her rights as a victim of abuse must be safeguarded.

1.5.1.1.1

Should the shaking be reported? If so, for what reasons?

The term “report” refers to any communication with the State Prosecutor concerning a child in danger or likely to become so.

A report to the State Prosecutor (with a copy sent to the Chairperson of the County Council) is essential. This will trigger a civil procedure (placing the child in care without delay) and a criminal inquiry (because shaking is an offence).

1.5.1.1.2

Discuss the case before reporting

An initial meeting involving at least two professionals must take place straight away. A meeting report must be drafted. An initial report can thus be submitted without delay. A more extensive medical, psychological and social evaluation will be performed later.

1.5.1.1.3

What happens once a report has been submitted?

1.5.1.1.3.1

The civil procedure

The State Prosecutor may deliver an OPP; this means that the child will be immediately placed under care and prevents the parents from recovering him/her when discharge to home would endanger the child. This decision has no right of appeal and is valid for one week, during which the case can be referred to a juvenile court. The latter will give a ruling within two weeks of taking up the matter and after having summoned the legal guardians. The judge may extend the OPP, issue a permanent care order (which can be appealed by the parents) or implement other educational assistance measures.

1.5.1.1.3.2

The criminal procedure

Referring the matter to the State Prosecutor will trigger an immediate criminal inquiry, in order to identify and potentially prosecute the perpetrator(s). In the event of death and if there is medical opposition to burial, a forensic autopsy can be ordered by the State Prosecutor.

1.5.1.1.4

Who can report a case of child abuse?

A report must be made to the competent authority without delay by: any person becoming aware of child abuse, any person working in a public- or private-sector establishment that becomes aware that a child is in danger or likely to become so, any public authority or any public servant becoming aware of a crime or offence in the exercise of his/her official duties.

It is important to bear in mind articles 226-13 and 226-14 of the Penal Code, which define physician-patient confidentiality. The other important articles in the Penal Code, the Social Action and Family Code, the Criminal Procedure Code and the French Code of Medical Ethics (article 44), are detailed in the Public Audition Commission’s advisory report.

1.5.1.1.5

To whom should shaking be reported?

Shaking is a serious act, which justifies referral of the matter to the State Prosecutor, in order to protect the child. A report is also justified by the fact that shaking is a criminal offence.

The State Prosecutor can issue an OPP, start a criminal inquiry and name an ad hoc legal guardian. He can also refer the matter to the CRIP (Section 1.8.5.2.1).

1.5.1.1.6

What information should the report contain?

The report per se is not defined in law. There are no legal or regulatory texts specifying the content of the report and the procedures for transmission to the State Prosecutor.

However, a certain number of rules must be followed, in order to provide an objective opinion:

- •

the person who reports the shaking must not accuse or refer by name to the perpetrator of what may be a criminal offence;

- •

it is important to make a clear distinction between the observed facts on one hand and reported accounts on the other. Always specify the source of the information (e.g. statements made by the parents or social services staff), in order to avoid any ambiguity for the recipient of the report. Use the conditional tense and an indirect style or put reported statements between quotes.

The report’s content may be as follows

Essential information:

- •

the recipient’s name and address.

- •

the report writer(s) name(s), job title(s) and professional address(es).

- •

the parents’ names, address(es) and telephone number(s).

- •

a chronological description of the facts concerning the child.

- •

initial medical observations, with the results of the main additional examinations and hypotheses concerning the cause of the lesions. If the initial medical certificate is attached, it is considered a separate document from the main report.

- •

information on the severity of the situation, justifying direct reporting to the State Prosecutor’s office.

- •

details on the immediate follow-up envisaged by the physician or medical staff.

- •

the date and signature(s).

Add the following to the initial report whenever possible:

- •

detailed administrative information concerning the family: composition, ages, professions, etc.;

- •

childcare procedures: parents, child-minder, crèche, other people;

- •

explanations for the observed lesions provided by the carers and the degree of compatibility between these explanations and the medical observations;

- •

people already contacted concerning the incident, citing the names, job titles and addresses of other professionals potentially contacted or involved (the County Childcare Office or Maternal and Child Health Office, a crèche, a day nursery, etc.).

Each hospital establishment should define the procedure to be followed by its staff in the event of a report to the State Prosecutor concerning shaken baby cases. The following advice can be given:

- •

draw up a document signed by both the hospital physician attending to the child and the social worker (and potentially completed by the psychologist or psychiatrist who had spoken with the family);

- •

when immediate child protection seems necessary, it is advisable to contact the State Prosecutor’s office by telephone and then confirm the report in writing, as follows:

- ∘

send the report by fax and by registered post with signed-for delivery, keeping a copy in the hospital file,

- ∘

send a copy to the Chairperson of the County Council, in accordance with article L. 226-4 of the Social Action and Family Code.

The report’s authors should ask to be kept informed of any subsequent action taken by the State Prosecutor.

1.5.1.1.7

When should a report be filed?

It is advisable to report the main details as rapidly as possible, in order to protect the child and not jeopardize the criminal inquiry: the sooner after the event the report is filed, the sooner an effective criminal inquiry can start.

However, this does not remove the imperative need to consult with colleagues before completing the report.

1.5.1.1.8

What impact will failure to report shaking have on the child?

A child can only receive legal protection if the State Prosecutor has taken up the case; the criminal inquiry, subsequent compensation and appointment of an ad hoc legal guardian also depend on this report.

1.5.1.1.9

What risks are incurred by professionals who do not report cases of shaking?

1.5.1.1.9.1

Risks incurred by the physician

Article 44 of the French Code of Medical Ethics obliges the physician, except under particular circumstances that he/she shall consider in all conscience, to alert the judicial, medical or administrative authorities in the event of abuse or privation in a child aged 15 or under.

For cases of severe abuse, a report to the State Prosecutor is recommended by the French Medical Council.

The fact that this obligation is accompanied by a conscience clause does not make it any less imperative. Hence, if the physician does not alert the authorities, he or she must explain the circumstances that prompted this decision. If a physician does invoke the conscience clause, he/she must nevertheless ensure that effective protective measures are implemented in order to avoid recurrence of the shaking or other abuse.

In the event of death and if shaking seems highly probable, the physician who delivers the death certificate must mention the fact that the death raises legal issues; if he/she does not, he/she may face criminal charges for falsification as well as disciplinary sanctions.

1.5.1.1.9.2

Risks incurred by other professionals

People subject to a professional duty of confidentiality may or may not choose to report crimes and abuse but always have a legal obligation to assist a person in danger.

1.5.1.1.10

What risks are incurred by professionals who report shaking?

There are no risks, except when the report could be considered as a knowingly false accusation, i.e. if it can be proved that the author of the report acted in bad faith with the intention to harm the accused person. The last paragraph of article 226-14 of the Penal Code states that “when performed under the conditions set out in the present article, reporting to the competent authorities cannot be the object of any disciplinary sanctions.”.

1.5.1.1.11

What information should be given to the parents? What are their rights?

The hospital staff must reconcile: the need for dialogue with the parents and the provision of information and the effectiveness of a criminal inquiry.

The parents must be informed of the report (except when this is not in the child’s interest) and the possibility of filing a complaint against person or persons unknown if they deny the shaking and attribute it to someone else.

The report is part of the legal file (and not the medical records) and can only be transmitted to the parents by the legal authorities.

1.5.1.1.12

What information should be given to other hospital staff and professionals outside the hospital?

The information circulated within the care team must be limited to the strict minimum required by each professional to establish a diagnosis, provide care or make a multidisciplinary evaluation of the situation or the need to protect the child.

The duty of confidentiality concerning this information applies not only to hospital staff but also to other people involved with the healthcare establishment (members of a patient association or volunteers, for example).

Regarding professionals based outside the healthcare establishment (social services staff, for example), it is important to communicate information that is required for protecting the child as part of their care duties (when evaluating the situation or deciding on whether the child should be placed under care or for follow-up).

1.5.1.1.13

What feedback will professionals receive following their report?

In return, the State Prosecutor’s Office must inform the reporter of any action subsequently taken: an on-going criminal inquiry, referral of the case to a juvenile court judge, etc. It is recommended that a form for this purpose be set up for communicating between the State Prosecutor’s Office and the person who filed the report.

1.5.1.1.14

Which measures may be taken by the State Prosecutor following a report of shaking?

A report sent to the State Prosecutor’s Office can trigger a child protection procedure and/or a criminal inquiry. Two parallel, complementary procedures may thus be launched. At the same time, an ad hoc legal guardian can be appointed.

The ad hoc legal guardian can be appointed by the State Prosecutor, the investigating magistrate, the juvenile court judge, the jurisdiction to which the criminal offence has been referred and the judge supervising a guardianship (if applicable).

The ad hoc legal guardian has both a legal duty and a role as a contact person and a support provider. He/she is independent with respect to the judge and the parents but must keep the judge informed about the major steps in the procedure and the performance of his/her duties.

The ad hoc legal guardian can refer the matter to the CIVI without waiting for the conclusion of the legal procedure.

1.5.1.1.14.1

The criminal inquiry

In France, criminal inquiries are led by the police force or the gendarmerie (usually a specialist child protection unit under the supervision of the State Prosecutor’s Office).

The members of the hospital team and professionals in contact with the family may be interviewed. They must state their knowledge of the situation and pass on any information or documents required for the purposes of the inquiry . Hospital and social services staff workers cannot claim an overriding professional duty of confidentiality when information is requested by a crime squad officer duly mandated and overseen by a legal authority.

If the physician receives a summons as part of a preliminary inquiry, he/she may communicate the facts known to him/her but is not obliged to do so – he/she can plead a professional duty of confidentiality.

Medical records may be requisitioned during the inquiry or investigation. This procedure must comply with and maintain physician-patient confidentiality.

Importantly, experts who become involved in the matter after the start of the judicial inquiry should be competent in the field concerned: paediatrics, ophthalmology, neurology, physical and rehabilitation medicine, radiology and even biomechanics.

1.5.1.1.14.2

The outcome of the criminal inquiry

The case may: be closed forthwith if the offense cannot be proven due to lack of evidence or lack of an identifiable perpetrator or give rise to a prosecution that may lead to dismissal of charges or a trial before a Magistrates Court (if the incident is considered to be a minor offence) or a Court of Assizes (for serious offences).

1.5.1.1.14.3

Initiation of a child protection procedure

If the matter is referred to a juvenile court judge, the latter usually orders an investigation and a 6-month care review procedure ( investigation et orientation éducative , IOE 7

7 Due to be renamed as a mesure judiciare d’investigation educative (MJIE).

, which may involve the child being taken into care immediately) and may decide on the subsequent application of a supervision order at the child’s domicile ( action éducative en milieu ouvert, AEMO) or placement of the child with a foster family or in institutional care.If the presumption of innocence leads to the dismissal of legal proceedings (in the event of doubt as to the intention to cause harm or the identity of the perpetrator), this of course should be no obstacle to the protection of the child.

1.5.1.1.14.4

What are the potential criminal charges and sentences for perpetrators of shaking?

There is no specific criminal charge of “shaking” per se but the latter act always constitutes a violation of the law. The usual criminal charges relate to involuntary or voluntary assault with aggravating circumstances. It is important to differentiate between the intent to shake and consideration of the consequences of this act: shaking cannot be qualified as an involuntary act.

The severity of the sentences handed down by the courts very clearly illustrates the importance of the disapprobation associated with all violent acts inflicted on a child under the age of 15 by an ascendant (the legal, natural, or adoptive parents or the grand-parents, if the child has been entrusted to them) or a person with responsibility for the child (a child-minder, the latter’s spouse or partner, a partner of one of the parents or any other person charged with looking after the child). The possible sentences are presented in detail in the Advisory Report.

In addition to the main perpetrator, other people in the child’s environment may be prosecuted for not having prevented a crime or offence against the child, failure to assist a person in danger or (for ascendants or persons with authority over the child) lack of care and endangerment of the child’s health.

Additional sentences may be handed down: a temporary or permanent professional ban for the person charged with looking after the child, for example.

1.5.1.1.14.5

Under which conditions can the victim receive compensation?

Compensation is possible once the act of shaking is established – It is therefore important that it be established, even if the perpetrator is never identified. Reporting the shaking to the legal authorities is essential for enabling the possible award of long-term compensation to the shaking victim.

The appointment of an ad hoc legal guardian compensates for the fact that the child has no legal competence.

Referral to the Crime Victim Compensation Committee (CIVI) is essential, regardless of whether the perpetrator is economically disadvantaged or has not been identified. The matter can be referred to the CIVI immediately, within three years of the date of the offence or in the year following the final verdict issued in a public or civil prosecution before the criminal courts. The fact that the victim is a child suspends the time restriction; The victim can pursue the matter before the CIVI up until his/her 21st birthday.

1.5.1.2

Second hypothesis: a diagnosis of “possible” shaken baby syndrome

If the diagnosis is one of “possible” SBS, the hospital team must consider the child’s situation: does home discharge pose a potential danger to the child? Does the child require protection?

1.5.1.2.1

Must “cause for concern” be reported or passed on?

Article L. 226-3 of the Social Action and Family Code (as modified by the French Child Protection Act dated March 5, 2007) states that “The Chairperson of the County Council is responsible for gathering, processing and evaluating (at any time and regardless of the source) disclosures of concern for children in danger or who may become so. The State representative and the legal authorities shall provide the said Chairperson with their assistance. A process for determining the procedures for collaboration between the State, the legal authorities, cooperating institutions and not-for-profit associations must be established”.

In this respect, hospital staff must report their concerns to the CRIP, in compliance with article L. 226-3 of the Social Action and Family Code.

1.5.1.2.2

Why should cause for concern be disclosed?

Notifying the CRIP of concern enables the need for child protection to be considered.

The CRIP may variously require additional psychological and social information, evaluate the situation, immediately or subsequently refer the matter to the State Prosecutor or suggest administrative protection.

1.5.1.2.3

What information should be given to the parents following a disclosure of concern?

The parents must be informed when a disclosure of cause for concern involves their child, except when this is contrary to the child’s interest.

1.5.1.2.4

Administrative protection of the child

The Chairperson of the County Council can, with the parents’ approval, implement administrative protection. He/she may refer the matter to the State Prosecutor if the parents refuse administrative protection or if the latter does not protect the child sufficiently.

1.5.1.2.5

Parental support

If child protection does not appear to be necessary but a need for help and support is apparent, certain parental support measures can be envisaged. Recourse to child protection staff (notably through home visits) must be considered. “Parent and child drop-in centres” at which the relationship between the parents and the child can be built or strengthened are recommended solutions.

1.5.1.3

Practical guidelines

In all cases, “all decisions must be guided by the child’s interest and consideration for its fundamental, physical, intellectual, social and affective needs and the defence of its rights”, in compliance with the first article of France’s Child Protection Act 2007-293 dated March 5, 2007 (codified as article L. 112-4 of the Social Action and Family Code).

1.5.1.3.1

Guidelines for hospital staff

1.5.1.3.1.1

Team coordination

For a diagnosis of “probable” SBS, the medical team (at least two healthcare professionals) must meet and review the symptoms and the reported facts, pool and compare the gathered information, make a diagnosis, consider (as appropriate) any other associated mistreatments, clarify each person’s positions and discuss whether a report should be filed. This meeting must take place without delay and must be summarized in writing. A report may be filed immediately.

In addition, a multidisciplinary medical, psychological and social evaluation of the situation is essential, in order to analyse the child’s situation, identify risk factors and consider the child’s future and potential protection measures. Consulting with colleagues is never a waste of time. The healthcare professional should not confuse speed and haste.

1.5.1.3.1.2

Reporting

Each hospital service should define the reporting procedures to be followed by its staff in cases of shaking, as follows:

- •

in urgent cases, establish an initial report that includes the essential information (see the text box above Section 1.8.5.1.6) and then add further information after a multidisciplinary evaluation;

- •

the report should be signed by the attending hospital physician and social services staff. In some cases, it may be completed by the psychologist or psychiatrist who has interviewed the family. It is essential to provide information on context and congruency as well as recording the medical facts;

- •

the report should be sent by both fax and registered post with signed-for delivery, while keeping a copy for the hospital records;

- •

if the report is sent directly to the State Prosecutor’s Office, a copy must be sent to the Chairperson of the County Council.

An OPP temporary placement order ordered by the State Prosecutor will not influence subsequent legal proceedings and is recommended – if only to provide the child with immediate protection.

Reporting should be performed as quickly as possible, in order to provide the child with immediate protection and not jeopardize the inquiry: the sooner after the event the report is filed, the sooner an effective criminal inquiry can start.

In this respect, the County’s procedure (established in compliance with the French Child Protection Act 2007-293 dated March 5, 2007) and involving the council itself, the State Prosecutor’s Office, hospitals and other parties likely to be aware of children in danger in general and shaking victims in particular) should contain advice that is clear and is applicable to the county as a whole.

As soon as a diagnosis of SBS is stated as the cause of (or one of the possible causes of) a baby’s death, the physician who delivers the death certificate must mention the fact that this death raises legal issues.

1.5.1.3.1.3

Dialogue with the parents and the family

In the diagnostic phase, dialogue with the parents is essential – notably in order to obtain their explanations concerning the child’s injuries. It is not a question here of forming an opinion on the circumstances of and justifications for shaking, identifying the perpetrator and deciding whether the latter should be prosecuted – these issues are the sole responsibility of the State Prosecutor.

The physician should inform the parents that in light of the severity of their child’s condition, the State Prosecutor’s Office will be contacted. He/she should also specify that the State Prosecutor will decide on any further actions to be taken. This approach, which means taking time and making an effort to listen, is best led by a senior physician in the presence of another staff member. It is essential to try to make the parents understand that the goal is not to denounce them but to draw attention to a dangerous situation and protect their child.

The parents must be informed of the report (except when contrary to the child’s interests), the possibility that an OPP may be issued by the State Prosecutor and the possibility of filing a complaint against person or persons unknown if they themselves agree there was shaking but attribute it to someone else.

However, this necessary dialogue and the obligation to provide the parents with information must not hinder or jeopardize the criminal inquiry.

1.5.1.3.1.4

Exchanging information with the State Prosecutor’s Office

It is recommended that a form be used for the exchange of information between the State Prosecutor’s Office and the reporting person. In order to establish this practice, the form should be part of the reporting protocol.

1.5.1.3.1.5

Requisition of medical records

It is advisable to photocopy requested documents prior to their transmission, in order to: comply with the healthcare establishment’s obligation to store its medical data and counter the risk of not having the requisitioned items returned.

It is advisable to request the return of requisitioned items. This request must be sent to the investigating judge if it is made during the legal proceedings (article 99, paragraph 1 of the Criminal Procedure Code) or to the ruling jurisdiction if the case is closed (Article 373 and article 484, paragraph 2 of the Criminal Procedure Code).

1.5.1.3.1.6

Disclosure of cause for concern

To disclose concern to the CRIP, the physician should follow the county’s procedure, in compliance with article L. 226-3 of the Social Action and Family Code 8

8 “…procedures to this end must be established by the Chairperson of the County Council, the State’s representative in the county and the legal authorities with a view to centralizing disclosures of concern within a specialist unit for gathering, processing and evaluating this information”.

.1.5.1.3.2

Guidelines for non-hospital-based medical staff

A medical condition as serious as SBS requires hospitalisation. Private practitioners and staff in child protection units should refer the child towards a paediatric care unit if they are in any doubt as to potential SBS.

The physician who refers the child must first contact the hospital staff. He/she must verify that the baby is taken to the hospital by the parents (failing which the physician remains fully responsible for the child’s safety).

Private practitioners and child protection units must be trained to diagnose SBS and to refer cases to an appropriate facility.

Joint continuing professional education sessions on SBS must be organized for all physicians practising outside hospital.

1.5.1.3.3

Guidelines for staff in county services

A disclosure of cause for concern pertaining to SBS must be processed as rapidly as possible (within one month at most) by the CRIP itself or by field-based professionals (in the district or from voluntary organizations).

Each CRIP should appoint a physician responsible for promoting the exchange and processing of medical information.

It is recommended to maintain continuous dialogue with the parents, in the spirit and letter of the French Child Protection Act dated March 5, 2007. The objective is to not only protect the child but also to help parents in difficulty with their baby.

County staff must inform the parents and obtain their consent for any administrative care procedures, in compliance with the parents’ rights and by encouraging the exercise of the said rights.

1.5.1.3.4

General guidelines

1.5.1.3.4.1

For professionals in contact with young children

Since many shaking incidents occur in child care facilities), initial training, continuing professional education and staff support must be implemented in order to maintain high levels of awareness.

In general, any professional likely to become aware of shaking incidents in some way must receive at least basic training on this issue: social services staff, child aid supervisors, magistrates, police officers, etc.

When justified by the context, it is advisable to identify all the resources that can potentially be leveraged in the family environment to help parents better fulfil their parental role. In general, personal and life problems experienced by people looking after children should act as a warning sign for any professionals who know about them.

1.5.1.3.4.2

For parents and families

It is advisable to organise frequent, appropriate awareness-raising and information campaigns (targeted at people in contact with babies, above all) on the dangers of shaking and the precautions that should be taken.

In maternity wards and in the days following discharge to home, parents should always be made aware of the danger of shaking.

“Parent and child drop-in centres” at which the relationship between the parents and the child can be built or strengthened are recommended solutions.

It is important to offer appropriate support to parents and implement support measures when requested. Referral to maternal and child health professionals (notably with home visits) must be envisaged. The same is true for various forms of home help (provided by social and family services).

1.5.1.3.4.3

In the child’s interest

We recommend that France borrows elements of Canadian law in which an ad hoc legal guardian can be appointed whenever necessary in the child’s interest and in defence of the child’s rights.

2

Version française

Ce texte est composé de trois parties. La première consacrée au diagnostic de secouement (signes d’appel, facteurs de risque, investigations à mener, lésions possibles) se conclut par la proposition de critères diagnostiques fondés sur l’histoire clinique et les lésions.

La deuxième partie étudie la possibilité pour des mécanismes souvent allégués telle la chute ou les manœuvre de réanimation d’induire des lésions comparables à celles du SBS. Elle étudie également l’éventualité de facteurs favorisant la survenue de lésions.

La troisième partie, enfin, est consacrée aux conséquences (dans le contexte réglementaire et législatif français) du diagnostic de secouement.

2.1

Abréviations

CIVI

commission d’indemnisation des victimes d’infraction pénale

CRIP

cellule de recueil, de traitement et d’évaluation des informations préoccupantes

EESA

expansion des espaces sous-arachnoïdiens

HR

hémorragie rétinienne

HSD

hématome sous-dural

IRM

imagerie par résonance magnétique

OPP

ordonnance de placement provisoire

SBS

syndrome du bébé secoué

2.2

Participants

Cette audition publique a été organisée par la Société française de médecine physique et de réadaptation (Sofmer), avec les participations suivantes :

- •

Collège national des généralistes enseignants

- •

Inserm

- •

InVS

- •

Société française d’anesthésie-réanimation

- •

Société française de médecine d’urgence

- •

Société française de médecine légale

- •

Société française de neurochirurgie pédiatrique

- •

Société française de neuropédiatrie

- •

Société française de pédiatrie

- •

Union nationale des associations de familles de traumatisés crâniens et cérébro-lésés (UNAFTC)

2.2.1

Financement

- •

Caisse d’assurance maladie des professions libérales de province

- •

Direction générale de la santé

- •

France traumatisme crânien

- •

Société française de médecine physique et de réadaptation

- •

Société francophone d’étude et de recherche sur les handicaps de l’enfance

- •

Caisse d’assurance maladie des professions libérales d’île-de-France

2.2.2

Comité d’organisation

- •

Dr Anne Laurent-Vannier, médecin de médecine physique et de réadaptation, Saint-Maurice – présidente du comité d’organisation

- •

Dr Juliette Bloch, médecin épidémiologiste, InVS, Saint-Maurice

- •

M. Thierry Boulouque, commissaire divisionnaire, chef de la brigade de protection des mineurs, Paris

- •

Dr Jeanne Caudron-Lora, urgentiste, Créteil

- •

Pr Brigitte Chabrol, pédiatre, Marseille

- •

M. Frédéric De Bels, HAS, Saint-Denis La-Plaine

- •

Dr Patrice Dosquet, HAS, Saint-Denis La-Plaine

- •

Mme Françoise Forêt, professeur honoraire, Union nationale des associations de familles de traumatisés crâniens et cérébro-lésés (UNAFTC), Paris

- •

Dr José Guarnieri, neurochirurgien, Valenciennes

- •

Pr Vincent Gautheron, médecin de médecine physique et de réadaptation, Saint-Étienne

- •

Dr Cyril Gitiaux, pédiatre, Paris

- •

Mme Anne-Sophie Jarnevic, magistrat, Chartres

- •

Mme Thérèse Michel, assistante sociale, Tours

- •

Pr Gilles Orliaguet, anesthésiste-réanimateur, Paris

- •

Dr Claude Rougeron, médecin généraliste, Anet

- •

Pr Michel Roussey, pédiatre, Rennes

- •

M. Yvon Tallec, magistrat, Paris

- •

Pr Gilles Tournel, médecin légiste, Lille

- •

Dr Anne Tursz, directeur de recherche, Inserm, Villejuif

2.2.3

Commission d’audition

- •

Dr Mireille Nathanson, pédiatre, Bondy – coprésidente de la commission d’audition

- •

Mme Fabienne Quiriau, directrice de la Convention nationale des associations de protection de l’enfant (CNAPE), Paris – coprésidente de la commission d’audition

- •

Mme Aurélie Assié, assistante sociale, Aide sociale à l’enfance de Paris, service d’accueil familial, Ecommoy

- •

Dr Joseph Burstyn, ophtalmologiste, Paris

- •

Dr Christine Cans, pédiatre, Grenoble

- •

Dr Catherine Arnaud, pédiatre, Toulouse

- •

Mme Violaine Chabardes, gendarme, Lyon

- •

Mme Hélène Collignon, journaliste, Paris

- •

Dr Marie Desurmont, médecin légiste, Lille

- •

Mme Isabelle Gagnaire, infirmière puéricultrice, Saint-Étienne

- •

Pr Nadine Girard, radiologue, Marseille

- •

Pr Étienne Javouhey, réanimateur, Lyon

- •

Dr Anne Laurent-Vannier, médecin de médecine physique et de réadaptation, Saint-Maurice

- •

M. Philippe Lemaire, magistrat, Paris

- •

Dr Caroline Mignot, pédiatre, Paris

- •

Dr Sylviane Peudenier, neuropédiatre, Brest

- •

Dr Bruno Racle, pédiatre, Versonnex

- •

Dr Pascale Rolland-Santana, médecin généraliste, Paris

- •

Dr Thomas Roujeau, neurochirurgien, Paris

- •

Dr Nathalie Vabres, pédiatre, Nantes

- •

Mme Roselyne Venot, fonctionnaire de police, Versailles

2.2.4

Chargés de la synthèse bibliographique

- •

Dr Élisabeth Briand-Huchet, pédiatre, Clamart

- •

M. Jon Cook, anthropologue, Villejuif

2.2.5

Experts

- •

Pr Thierry Billette de Villemeur, pédiatre, Paris

- •

Pr Jean Chazal, neurochirurgien, Clermont-Ferrand

- •

Pr Catherine Christophe, radiologue, Bruxelles

- •

Dr Sabine Defoort-Dhellemmes, ophtalmologiste, Lille

- •

Dr Gilles Fortin, pédiatre, Montréal

- •

Dr Caroline Rambaud, médecin légiste, Garches

- •

Pr Jean-Sébastien Raul, neurochirurgien, Strasbourg

- •

Dr Caroline Rey-Salmon, pédiatre, Paris

- •

M. François Sottet, magistrat, Paris

- •

Mme Élisabeth Vieux, magistrat honoraire, Paris

- •

Pr Mathieu Vinchon, neurochirurgien, Lille

- •

Pr Rémy Willinger, professeur de mécanique, Strasbourg

Iconographie mise à disposition par la Société francophone d’imagerie pédiatrique et prénatale (SFIPP).

2.3

Recommandations

2.3.1

Secouement : démarche diagnostique

Le SBS est un sous-ensemble des traumatismes crâniens infligés ou traumatismes crâniens non accidentels, dans lequel c’est le secouement, seul ou associé à un impact, qui provoque le traumatisme crânien. Il survient la plupart du temps chez un nourrisson de moins de 1 an.

Chaque année, 180 à 200 enfants seraient victimes, en France, de cette forme de maltraitance ; ce chiffre est certainement sous-évalué. La méconnaissance du diagnostic expose au risque de récidive.

2.3.1.1

Chez un nourrisson, vivant ou décédé, quels sont les signes cliniques pouvant ou devant faire évoquer le diagnostic, ou risquant d’égarer le diagnostic ?

2.3.1.1.1

Symptômes initiaux

Les symptômes initiaux sont comme suit :

- •

dans les cas les plus graves, « l’enfant a été trouvé mort ». Il est essentiel de suivre dans ce cas les recommandations de la Haute Autorité de santé 9

9 Prise en charge en cas de mort inattendue du nourrisson (moins de deux ans). Recommandations de bonne pratique. HAS. Février 2007.

. En particulier l’autopsie est essentielle ; sauf indication médicolégale et décision du procureur de la République, elle requiert l’autorisation des parents ;

- •

« une atteinte neurologique grave » peut être évoquée d’emblée : malaise grave, troubles de la vigilance allant jusqu’au coma, apnées sévères, convulsions, plafonnement du regard, signes orientant vers une hypertension intracrânienne aiguë, voire vers un engagement ;

- •

« d’autres signes orientent aussi vers une atteinte neurologique » : moins bon contact, diminution des compétences de l’enfant ;

- •

« certains signes non spécifiques d’atteinte neurologique » peuvent égarer le diagnostic : modifications du comportement (irritabilité, modifications du sommeil ou des prises alimentaires), vomissements, pauses respiratoires, pâleur, bébé douloureux.

L’examen clinique doit être complet, sur un nourrisson dénudé ; il comprend en particulier la palpation de la fontanelle, la mesure du périmètre crânien qu’il faut reporter sur la courbe en cherchant un changement de couloir, la recherche d’ecchymoses sur tout le corps, y compris sur le cuir chevelu.

Étant donné l’absence de spécificité de certains signes, « leur association » présente un intérêt majeur : association de vomissements avec une tension de la fontanelle, des convulsions, une hypotonie axiale, un trouble de la vigilance ; association de convulsions avec une hypotonie axiale, une tension de la fontanelle ; tension de la fontanelle avec cassure vers le haut de la courbe de périmètre crânien.

2.3.1.1.2

Absence d’intervalle libre

Dans la majorité des cas, sinon dans tous les cas, le secouement entraîne immédiatement des symptômes. Cela est bien sûr distinct du fait qu’il peut y avoir un délai entre le secouement et la consultation.

2.3.1.1.3

Autres éléments pouvant faire évoquer un secouement

Les autres éléments sont :

- •

données de l’anamnèse :

- ∘

retard de recours aux soins,

- ∘

absence d’explications des signes, ou explications incompatibles avec le tableau clinique ou le stade de développement de l’enfant, ou explications changeantes selon le moment ou la personne interrogée,

- ∘

histoire spontanément rapportée d’un traumatisme crânien minime,

- ∘

consultations antérieures pour pleurs ou traumatisme quel qu’il soit,

- ∘

histoire de mort(s) non expliquée(s) dans la fratrie ;

- ∘

- •

facteurs de risque :

- ∘

les bébés secoués sont plus souvent des garçons, des prématurés ou des enfants issus de grossesses multiples,

- ∘

l’auteur du secouement est la plupart du temps un homme vivant avec la mère (qui peut être le père de l’enfant ou le compagnon de la mère), mais les gardiens de l’enfant sont en cause dans environ 1 cas sur 5,

- ∘

tous les milieux socioéconomiques, culturels, intellectuels peuvent être concernés, mais il a été noté, d’une part, qu’une histoire de consommation d’alcool, de substance illicite ou de violence familiale est un facteur de risque, d’autre part, que les auteurs du secouement ont souvent une méconnaissance importante des besoins ou comportements normaux de leur enfant,

- ∘

il existe fréquemment un isolement social et familial des parents.

2.3.1.1.4

Faut-il hospitaliser ?

Penser au diagnostic de secouement doit conduire le médecin à faire part aux parents de son inquiétude sur l’état de l’enfant et à poser l’indication d’une hospitalisation en urgence.

2.3.1.2

Quelles sont les lésions et quel est le bilan clinique et paraclinique nécessaire et suffisant à leur mise en évidence ?

2.3.1.2.1

Lésions observées en cas de secouement

Sont susceptibles d’être lésés dans le SBS les méninges, l’encéphale, l’œil et la moelle épinière. D’autres lésions peuvent être associées : lésions du cou et du rachis cervical, fractures des membres, des côtes, du crâne, ecchymoses et hématomes des téguments, des muscles du cou:

- •

lésions intracrâniennes :

- ∘

hématomes sous-duraux (HSD) :

- –

habituellement plurifocaux ( Fig. 1–3 ) qui peuvent être associés à des hémorragies sous-arachnoïdiennes,

- –

mais l’HSD peut être unifocal,

- –

une hémorragie au niveau de la faux du cerveau ou de la fosse postérieure est très évocatrice du diagnostic,

- –

les hématomes sous-duraux ne sont pas constants dans le SBS ;

- –

- ∘

lésions cérébrales : elles peuvent être anoxiques, œdémateuses ou à type de contusion ;

- ∘

- •

hémorragies rétiniennes :

- ∘

les hémorragies rétiniennes (HR) sont quasi-pathognomoniques de SBS quand elles sont multiples, profuses ou éclaboussant la rétine jusqu’à sa périphérie, avec parfois rétinoschisis hémorragique, pli rétinien périmaculaire (HR de type 3, Tableau 1 ),

- ∘

mais d’autres types d’HR peuvent se voir,

- ∘

elles sont absentes dans environ 20 % des cas. Elles ne sont donc pas indispensables au diagnostic, mais leur présence est un argument fort en faveur du diagnostic de secouement ;

- ∘

- •

lésions cutanées : les ecchymoses sont, en l’absence de cause médicale, très évocatrices de mauvais traitements chez un enfant qui ne marche pas seul ;

- •

lésions osseuses : les lésions osseuses sont évocatrices de mauvais traitements, particulièrement les fractures de côtes ou les images de cals costaux, les arrachements métaphysaires, les appositions périostées ;

- •

lésions des muscles du cou, du rachis ou de la moelle cervicale.