Chapter 8. A model for dementia care

Chapter Contents

Introduction117

The reflective phase118

The symbolic phase122

The sensorimotor phase126

The reflex phase130

INTRODUCTION

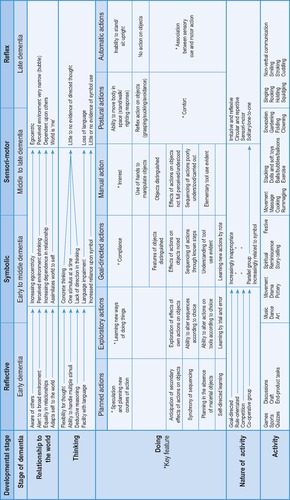

This model (we will continue to use this term simply because it is the easiest and most descriptive) is based upon the Piagetian theory of cognitive development first discussed in Chapter 3. We have also been influenced by the developmental models of occupational therapists Ann Cronin Mosey, 1981 and Mosey, 1986 and Claudia Kay Allen (the ‘doing’ section of Fig. 8.1 is adapted from Allen, Earhart & Blue’s six cognitive levels, 1992). However, it would be true to say that both Mosey and Allen were also influenced by Piaget, amongst others. We have, in addition, drawn from the ideas of Donald Winnicott, whose seminal work on human development and the development of ‘self’ cannot be ignored.

We have attempted to put together a model which illustrates the cognitive changes that take place across the course of a dementia, and thereby the changes to an individual’s ability to ‘do’. Perhaps a word needs to be said, before proceeding further, about the use of stages and categories, columns and boxes. There are those who are uncomfortable about applying stages to dementia, believing this to be somehow a denial of individuality and personhood, and counterproductive to the therapeutic task. There is little logic in such a notion, though there may for some be a temptation to put people into boxes alongside the information, understanding their experience as having clearly defined parameters. We hope that our model will not be used in such a way. We use boxes for the purpose of ordering and structuring concepts, not people. The model should bend to the person, not the other way round, and we believe that this schema is sufficiently flexible to accommodate the diversity of individual experience over the course of dementia.

We like to understand the model in terms of the four developmental stages broadly described by Piaget as the reflective, the representational (we prefer the term symbolic, but the meaning is the same), the sensorimotor and the reflex. We shall address this discussion to those four headings, although it goes without saying that there are no definitive dividing lines between stages, and a considerable blurring of edges.

THE REFLECTIVE PHASE

In the young person whose cognitive development is progressing normally, this is the period of mid to late teens, characterised by a move towards mature, adult functioning. In dementia, we understand this to be that period where the first tell-tale signs of a dementing condition are starting to intrude into an otherwise healthy cognition.

Relationship to the world

Awareness of people, things and events is intact, even in the broader unseen environment represented by the individual’s ability to use symbol and image. Fully developed intellectual powers and social faculties foster the capacity for self-maintenance and change, and adaptation to the vicissitudes of life in the world is a key feature. A person can bend to the influences of the environment upon him, and allow himself to change in order to accommodate them. This retention of a social awareness permits new relationships to be established, and existing relationships to continue in an equality of give and take.

Doing

Doing is inextricably linked to thinking in this phase, and is characterised by planned actions, actions in which many component parts are set in sequence. Known sequences are understood and new sequences may be explored. The flexibility of thinking which characterises this stage permits changes to be made to existing relationships between actions, and between actions and objects, and facilitates the creation of new relationships. Learning is self-determined and self-directed.

Nature of activity

The type of activity predominantly engaged in by those with cognitive faculties intact is both goal-directed and rule-oriented. There is invariably a goal, an end-in-view; a person has the ability to retain that goal in his inner vision, to make plans, and to effect actions and employ objects which will enable him to move towards that goal. Rules also will often dominate activity at this stage, although they may be more commonly understood as methods or procedures or patterns. They are nevertheless rules – specified ways of doing things. Memory and comprehension are intact, and rules are therefore retained and understood, and used to structure and drive actions. Where such activity is carried out with other people, it will often be in the context of a cooperative group setting, where it is the interdependency of the parties involved which determines the achieving of the goal. Competition is often a feature of the cooperative group setting, and can contribute an additional dimension of zeal and zest in the drive towards attaining the goal.

Possible activities

Any activity which fulfills the criteria outlined above has potential for inclusion at this stage. Structured crafts which follow a pattern or a set of instructions are appropriate, such as a knitted garment, a soft toy, painting by numbers or a wooden bird table. Tasks perceived as more ‘work’ oriented also fit the bill: for example, typing a letter, doing the washing up, getting the shopping, building a wall. Games and sports also operate in the context of goals and rules, and have the added components of cooperative interaction and competition. There are the ‘head-to-head’ games of chess, draughts and snooker; small group games of Monopoly, cards and Scrabble; and games with a potential for larger group participation such as darts and bowls and party games of all sorts. The variety of course is almost endless. Quizzes also may be embraced under this heading, as may discussions. The rules governing discussions may be less evident and more informal than in a game, but they are there nevertheless: rules (usually unwritten) about leadership and turn-taking and sequencing, without an understanding of which chaos is likely to ensue. Goals too are often less clear – to convey information, to solicit opinion, to resolve argument – but still an integral feature.

It is important to note at this point that activities which we have categorised under ‘earlier’ developmental stages, i.e. the symbolic, the sensorimotor and the reflex, are not excluded from this reflective phase. Any of the activities listed in other phases may, of course, be welcomed by the person in early dementia. As a general rule, we might say that any activity categorised by the model at an earlier stage to the one the person is in, has a potential for therapeutic benefit. The reverse is not necessarily the case. Any activity categorised by the model at a later stage to the one the person is in has a potential to be counterproductive, perhaps even damaging. For example, a person who is in the reflective phase of a dementia may of course welcome, enjoy and derive great benefit from an activity which we have included at the sensorimotor stage, such as a massage, or a party balloon game. We all know the potential for pleasure and relaxation of activities where we don’t have to think or plan. However, a person who is in the sensorimotor stage of a dementia is very unlikely to enjoy or even participate in a quiz or a game of dominoes, and attempts to encourage such a person in this direction are likely to exert pressure and induce stress; they will not be therapeutic. This is discussed in more detail below.

Examples

This section under each phase heading is designed to illustrate how a core activity may be used across all four phases of the model, with changes to accommodate it to the differing requirements of each phase. There are a number we could have chosen, but we have opted for activity related to food, activity involving music, and, perhaps because it is still a contentious issue for some people, activity using a doll.

There are a number of options related to working with food in this reflective category. One person may simply benefit from the experience of following a well-loved recipe, stage by stage, task by task; another may want to prepare a snack for a visiting relative, another to make some jam for the local fête. A cooperative element may be introduced with a group session to provide the food for a Caribbean (Thai? Scandinavian?) evening or a ‘hunger lunch’ for charity. A competitive dimension might be introduced in encouraging entries for the Victoria Sandwich Class at the local horticultural show.

There is a large range of possibilities for using music at this stage, from learning an instrument, to forming a small choir, to participating in a music appreciation class, to a karaoke competition.

Working with dolls in this phase could actually involve making or constructing a doll or puppet for a child or for a children’s hospital or group, or possibly even putting on a puppet show; it could be in the nature of a ‘dress the doll’ competition for the sewing circle; or it could be the group design and building of a dolls’ house to be donated to a good cause.

THE SYMBOLIC PHASE

Relationship to the world

This is a phase of which a key feature is an increasing egocentricity or, as we have described it elsewhere (p. 63/64), a failure to perceive a progressively narrowing environmental field. The growing difficulty in perceiving and understanding the world of ‘other’ and ‘out there’ leads to difficulties in relationship, and to increasing dependence upon others for wellbeing and survival. The ability to adapt to external environmental influences is diminishing, and is being replaced by a delusory mechanism in which it is the world which changes. So for example, the lady whose purse is not in her handbag when she goes to look for it, is no longer able to say, ‘I must have put it somewhere else; I’d better look for it’ (adapting self to the world), but is quite likely to accuse the nearest other person of having stolen/removed it (assimilating world to self): ‘It cannot be me, because I always keep my purse in my bag, and I have no recollection of putting it anywhere else. It must therefore be someone else’.

Piaget has suggested that in the child, this symbolic period gives way to the reflective period as the child finds more and more opportunity to satisfy needs through his inter-relationships in real life; he has less and less need of recourse to symbolic ‘make-believe’:

‘In a general way it can be said that the more the child adapts himself to the natural and social world the less he indulges in symbolic distortions and transpositions, because instead of assimilating the external world to the ego he progressively subordinates the ego to reality.’ (Piaget 1951)

In our dementia care, we need to turn this statement around and recognise implicit in it the suggestion that the dementing person, unable by reason of cognitive impairment to ‘subordinate the ego to reality’, uses symbolic distortion and transposition to ‘assimilate the external world to the ego’.

The example of Frank comes to mind. Frank, though disoriented and memory impaired, was able at one level to acknowledge his wife’s death and his own admission to a residential home. However, much of the time he clearly chose to ‘live’ on another level, in which the residential home was The Queens (a local ballroom), where he was waiting for his wife to join him for the evening dance. He was able to acknowledge that on this level he could be in some measure content. He was, in effect, using symbol (wife alive and waiting, and The Queens ballroom) to assimilate a harsh and unacceptable external world to the ego. He appeared at this stage to be hovering on the border between the reflective and symbolic condition. As time went by, his thinking seemed to become more entrenched, settling him ever more firmly in the symbolic. We would suggest that this proposition accounts also for the innumerable episodes of ‘Mother will be waiting for me’ and ‘I must get home to get dinner for the boys’, that are so familiar to every dementia carer.

Thinking

Thinking is becoming increasingly ‘concrete’, inflexible and fragmented. The number of stimuli that can be accommodated in the course of mental processing is reduced, and the ability for sustained and focused thinking is declining. Language difficulties appear, and reflect disordered thought processes. There is an increased reliance upon symbol and ‘fantasy’ as higher critical powers diminish.

Doing

‘Doing’ in the symbolic phase tends to reflect the lack of flexibility evident in the cognitive realm. The ingrained actions of long-standing habits and routines and tool use are retained. Familiar objects will, by and large, be used and handled appropriately. But this is a phase which is characterised by a retreat from newness and complexity. Learning is possible (and demonstrable), but only through constant repetition, over and over again.

Nature of activity

Those principles which govern the activity of the previous, reflective phase are becoming increasingly inappropriate as a dementia progresses. The cognitive faculties required to hang on to future goals, and to make sense of sets of rules and procedures, are declining. There is therefore a need to look away from activities which are so driven. Competition also needs careful handling here. It may still, in some circumstances, provide a healthy buzz to an activity, but we need to beware of pitting somebody against his own dwindling abilities, and setting him up for failure. The quiz is a good example of an activity which can be (and often has been) misused in such a way – we need to be absolutely sure that we are not reinforcing a person’s self-awareness of cognitive losses. It is only too easy to do.

As the social world of the person in this phase begins to fracture, the group setting which relies upon cooperative interaction for its function becomes increasingly inappropriate. Socialising naturally continues to be important, but we might expect that a parallel group setting will now be more comfortable for the person whose social skills are declining. A parallel group, such as the reminiscence group or the knitting circle, provides opportunity for sociality, without the demand or expectation of interaction. People can be together, without having to work together, and the group will function with or without any given individual.

The key to understanding therapeutic activity at this stage is that it is increasingly related to symbol. If, as suggested above, a person is sufficiently cognitively impaired that they are using symbolic distortion and transposition to assimilate the external world to the ego, then maybe we need to give credence to the world of fantasy in a way that we have not done before. Traditionally pragmatic, occupational therapists may have some difficulty with such a notion, but it is nevertheless an idea which merits attention. Cox (see Chapter 5) attributes great weight to the value of fantasy in human survival, seeing it as essentially a creative mechanism which facilitates adaptation, innovation and change. It is not hard to see the delusional talk and behaviour of dementia in such a light: that it is a creative way of surviving, of accommodating the loss and damage of cognitive impairment. Such in fact is the basic theory underpinning Naomi Feil’s validation therapy; indeed her alternative title was ‘fantasy therapy’, though this is not commonly used (Feil 1982). The essential principle of such an approach then, is that practitioners should actively address and explore the ‘fantasy’ statement or action, acknowledging its survival function and understanding its creative drive. This may be a new departure for many practitioners, but it must be addressed if we are serious about the wellbeing of our clients with dementia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree