Acetabular fractures in the elderly are most frequently the result of low-energy trauma and present unique management challenges to orthopedic surgeons. Evaluation and treatment should be performed in a multidisciplinary fashion with early involvement of internal medicine subspecialists and geriatricians. Distinct fracture patterns and pre-existing osteoarthritis and osteoporosis necessitate careful preoperative planning. The role of total hip arthroplasty should also be considered when surgical treatment is indicated. The outcomes of acetabular fractures in the elderly have improved, but complications remain higher and results less satisfactory than in younger individuals. The lack of randomized controlled trials has limited the ability to establish an evidence-based treatment algorithm.

Key points

- •

The rate of acetabular fractures in the elderly is on the rise.

- •

Acetabular fractures in the elderly are more frequently caused by a low-energy mechanism, leading to characteristic fracture patterns.

- •

Geriatric patients often have multiple medical comorbidities and a multidisciplinary approach should be taken to their management.

- •

Acute total hip arthroplasty should be considered in a select group of elderly patients.

Epidemiology

As the elderly patient population continues to pursue more active lifestyles, the incidence of pelvic and acetabular fractures in the elderly is on the rise. Epidemiologic studies, starting in the 1970s, have demonstrated a steady increase in the global incidence of pelvic fractures sustained by individuals older than age 60. This trend is expected to continue as the elderly population increases with 20% of the United States estimated to be older than the age of 65 years by 2030. Kannus and colleagues reviewed first time, low-energy, osteoporotic pelvic fractures in patients older than age 60 from the Finnish national trauma registry from 1970 through 1997. They found the number of elderly pelvic fractures increased by an average of 23% per year and the incidence of osteoporotic pelvic fractures as a percentage of all pelvic fractures increased from 18% to 64%. Similarly, Gansslen and colleagues in a large, multicenter study from Germany reviewed 3260 patients of all ages with pelvic trauma and reported an increase in the incidence of pelvic trauma among patients aged 50 to 70 years from 1972 to 1993. The influence of age on the annual incidence of pelvic fractures cannot be overstated, because a four-fold increase is seen in patients greater than 80 years compared with 60 years of age.

Fractures of the acetabulum in elderly individuals are the fastest growing segment of pelvic trauma. Estimated to account for between 10% and 20% of all osteoporotic pelvic fractures, the incidence of acetabular fractures has risen concurrent with all types of pelvic fractures in the geriatric age group. Laird and Keating demonstrated an increase in the average age of individuals with acetabular fractures from 1988 to 2003 at a single institution in Edinburgh, Scotland. In the United States, Ferguson and colleagues retrospectively reviewed records from 1980 to 2007 and found the percentage of displaced acetabular fractures in patients older than age 60 increased from 10% to 24% of the total number of displaced acetabular fractures in patients of all ages.

Epidemiology

As the elderly patient population continues to pursue more active lifestyles, the incidence of pelvic and acetabular fractures in the elderly is on the rise. Epidemiologic studies, starting in the 1970s, have demonstrated a steady increase in the global incidence of pelvic fractures sustained by individuals older than age 60. This trend is expected to continue as the elderly population increases with 20% of the United States estimated to be older than the age of 65 years by 2030. Kannus and colleagues reviewed first time, low-energy, osteoporotic pelvic fractures in patients older than age 60 from the Finnish national trauma registry from 1970 through 1997. They found the number of elderly pelvic fractures increased by an average of 23% per year and the incidence of osteoporotic pelvic fractures as a percentage of all pelvic fractures increased from 18% to 64%. Similarly, Gansslen and colleagues in a large, multicenter study from Germany reviewed 3260 patients of all ages with pelvic trauma and reported an increase in the incidence of pelvic trauma among patients aged 50 to 70 years from 1972 to 1993. The influence of age on the annual incidence of pelvic fractures cannot be overstated, because a four-fold increase is seen in patients greater than 80 years compared with 60 years of age.

Fractures of the acetabulum in elderly individuals are the fastest growing segment of pelvic trauma. Estimated to account for between 10% and 20% of all osteoporotic pelvic fractures, the incidence of acetabular fractures has risen concurrent with all types of pelvic fractures in the geriatric age group. Laird and Keating demonstrated an increase in the average age of individuals with acetabular fractures from 1988 to 2003 at a single institution in Edinburgh, Scotland. In the United States, Ferguson and colleagues retrospectively reviewed records from 1980 to 2007 and found the percentage of displaced acetabular fractures in patients older than age 60 increased from 10% to 24% of the total number of displaced acetabular fractures in patients of all ages.

Mechanism of injury

Low-energy falls from standing height are the predominant mechanism of injury responsible for acetabular fractures in the elderly. This is different from the typical high-energy trauma from motor vehicle accidents or from high falls that are responsible for most acetabular fractures seen in the younger population. The positive correlation of age with fall from standing height resulting in injury is well known and thought to be the result of cognitive decline and motor impairment. An estimated 30% of people older than age 65 and 40% of people older than age 80 fall and sustain an injury significant enough to warrant a visit to the emergency department annually.

Importantly, when compared with younger individuals, seemingly low-energy falls cause significant injury and are the leading cause of injury-related death in the elderly population. Sterling and colleagues retrospectively reviewed data from a level two trauma center registry between 1994 and 1998 and found an injury severity score of greater than 15 in 30% of patients older than 65 compared with only 4% of patients younger than 65 who sustained a same level fall. The older cohort was more likely to sustain head, neck, chest, and pelvic injuries than the younger population and nearly twice as likely to die from a fall from any level.

Acetabular fracture patterns

Overall, associated both-column fractures are the most common acetabular fracture pattern observed in young and old individuals, accounting for 20% to 30% of acetabular fractures. However, several unique features and fracture patterns are observed more commonly in elderly individuals, reflecting the difference in dominant mechanisms of injury.

Although high-energy trauma is responsible for most acetabular fractures in young patients, low-energy falls are the predominant mechanism of injury in the elderly, typically resulting in lateral compression type injuries. The force from a direct impact on the greater trochanter is transmitted anteromedially to the anterior column, anterior wall, and quadrilateral plate. As a result, fractures of these structures are more common in the elderly compared with younger individuals, who are more likely to sustain injury to the posterior column and wall and transverse patterns. In the elderly, posterior wall involvement is more frequently associated with marginal impaction, comminution, and posterior hip dislocation than in young patients. These features, and medial roof impaction, quadrilateral plate fracture, and injury to the femoral head, which are also seen at an increased rate in the elderly, are associated with poor outcomes after open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of acetabular fractures in the elderly.

Initial evaluation

Even before arrival to the hospital, elderly patients are often undertriaged because of failure of emergency responders to recognize potential major injuries. Several studies have demonstrated an increase in morbidity and mortality when elderly trauma patients are delayed in their arrival to a high-level trauma center. Vital to every new clinical encounter, a thorough history should include assessment of the magnitude of the injury and the risk for concomitant injuries. Specific to the elderly, assessment of comorbidities, preinjury ambulatory status, and life expectancy are essential during the initial assessment, because they play a role in treatment decisions. The two most widely accepted and validated methods for assessment of comorbidities in the elderly population are the Charlson index and the American Society of Anesthesiologists Classification (ASA) index.

A high level of suspicion for severe injuries should be maintained during the evaluation of elderly patients, because they report less pain than younger patients for the same injury. Additionally, when elderly patients do sustain high-energy trauma, they are significant more likely to be polytraumatized than younger patients. Preexisting cognitive deficits, hearing difficulty, and other issues confound the use of the Glasgow Coma Scale in elderly patients. Additionally, the initial trauma evaluation and physical examination of geriatric patients is different than for that of younger patients because of changes in their physiology, making evaluation and treatment difficult. Specifically, vital signs considered within normal limits for younger patients, including heart rates greater than 90 beats per minute or systolic blood pressures less than 110 mm Hg, in the trauma setting, are associated with increased mortality in elderly patients. Magnussen and colleagues demonstrated that bleeding in acetabular fractures and age are directly correlated. Frequently lacking the cardiac reserve to adequately compensate, special attention should be paid to adequately resuscitating elderly patients to improve their chance of survival.

Interdisciplinary approaches, with early involvement of geriatric specialists, have been shown to result in decreased hospital stays and reduced cost in protocol-driven programs for elderly patients with hip fractures. In one study by Zuckerman and colleagues, elderly patients with hip fractures treated in a multidisciplinary program were found to have fewer complications, fewer intensive care unit transfers, decreased mortality, improved ambulation, fewer discharges to long-term care facilities, and a 33% reduction in the cost of care when compared with age-matched control subjects not enrolled in the program.

Diagnostic imaging

Following initial assessment, patients with suspected pelvic trauma should undergo conventional radiographs consisting of anteroposterior, obturator, and iliac oblique views. Frequently, patients undergo computed tomographic (CT) scan in their trauma work-up and the transaxial CT scan is useful in further fracture classification and for identifying acetabular impaction when section thickness is 3 mm or less. Reformatted CT images in the sagittal or coronal plan are valuable for identifying central acetabular impaction, whereas three-dimensional CT scans are useful for characterizing rotational deformities of the fragments. Although most fractures can be identified easily with plain radiographs or CT scan, up to 5% of acetabular fractures are not detected on initial imaging. When plain radiographs and CT scans fail to demonstrate pathology, but the clinical suspicion remains high, MRI and technetium bone scan have been found to have increased sensitivity in detecting nondisplaced insufficiency fractures common in osteoporotic bone. In one study by Hakkarinen and colleagues CT scan missed up to 20% of occult hip fractures that were subsequently detected on MRI, leading them to conclude that a negative CT scan is inadequate to exclude the diagnosis of acetabular fracture.

Surgical timing

The timing of surgery for acetabular fractures is a complex issue influenced by the resuscitation status of the patient, the fracture pattern and proposed surgical approach, and the requirement and availability of blood products. Conflicting reports exist in the literature regarding exact timing of surgery for elderly patients and results of studies in younger patients. Vallier and colleagues demonstrated that early definitive fixation reduces morbidity and intensive care stay may not necessarily be generalizable to geriatric patients. Zuckerman and colleagues found that delays of greater than 2 days resulted in a two-fold increase in mortality 1 year postoperatively. However, another study by Sexson and Lehner evaluating patients with three or greater comorbidities found a lower survival rate in those treated within 24 hours of admission. Thus, preoperative evaluation and risk assessment by anesthesia and medicine are essential because elderly patients are susceptible to cardiac and pulmonary events, have decreased compensatory reserve, become coagulopathic more quickly, and have a higher risk of venous tears. Because of the high risk of blood loss attributable to the size of the incision and difficulty in applying reduction clamps to osteoporotic bone, the surgical team should be prepared for blood transfusion. Some purport the benefits of a cell saver machine, although one study by Scannell and colleagues demonstrated that there was no change in intraoperative and postoperative transfusion when cell saver was used during surgical management of acetabular fractures. The use of cell saver was, however, associated with higher total blood-related charges.

Treatment

The treatment of acetabular fractures in the elderly is as varied as their presentation. Also, the heterogeneous nature of this specific population might complicate what is the optimal treatment of this injury. Other considerations include the capabilities of the treatment facility and the surgical skill of the treating surgeon. In the literature, there is a paucity of controlled, systemic reviews that might allow surgeons to reach adequate treatment conclusions. Options for the treatment of acetabular fractures in the elderly include nonoperative management; minimally invasive stabilization; conventional ORIF; delayed arthroplasty; or the combined hip procedure, which includes acute arthroplasty.

Nonoperative management

Nonoperative management should only be undertaken when it is expected to lead to good functional outcome with return to near preinjury activity level and not because no other options are available. This treatment strategy may be undertaken for several reasons pertaining to fracture pattern and patient factors:

- •

Minimally displaced, intrinsically stable injury patterns (eg, transverse type or anterior column fractures).

- •

Fractures with secondary congruence of the hip joint. This is frequently observed with both-column injuries where there is no continuity of the articular surface to the hemipelvis, but a congruent relationship is maintained between the femoral head and the acetabulum.

- •

Significant medical comorbidities that contraindicate surgery.

- •

Severely limited preinjury mobility.

Several acetabular injury patterns have consistently demonstrated poor results with nonoperative management. In these cases, efforts should be made to perform surgical treatment whenever possible.

- •

Posterior instability caused by a large posterior wall fragment or posterior comminution. In these cases, even bed-to-chair transfers cause fracture displacement and possible hip dislocation because the moving from a recumbent to seated position forces the femoral head posteriorly against the unstable fracture.

- •

Involvement of the weight-bearing dome.

- •

Quadrilateral plate impaction with medialization of the femoral head.

Nonoperative treatment should typically encompass bed-to-chair transfers followed by ambulation with assistance. Early mobilization is critical to avoid medical complications associated with prolonged recumbence. Strict bed rest is never indicated in management of these injuries. Partial weight-bearing should be initiated early on the affected extremity as tolerated. Although late displacement is uncommon if radiographs at 1 week are satisfactory, close radiographic follow-up should be performed to monitor for displacement, which may require a change in treatment strategy.

Traction should not be used as definitive treatment of any acetabular fracture in the elderly. Hip capsular ligamentotaxis is unable to reliably correct the deforming forces that are typically rotational, not translational. Additionally, a high rate of complications is observed, including medical issues from the requisite prolonged recumbence and pin site infections or pin pullout from osteoporotic bone.

Minimally invasive fixation

Minimally invasive fixation of geriatric acetabular fractures is a technically challenging technique that may be used for a small subset of minimally displaced yet unstable fracture patterns. Using small stab incisions, modified clamps and ball spike pushers can be used to achieve reduction. Cannulated screws are then inserted in a percutaneous fashion.

Advantages of minimally invasive fixation include a reduced surgical physiologic insult versus traditional ORIF. This allows for surgical stabilization and early mobilization in a patient who otherwise might not be a candidate for a large open procedure.

It also makes future arthroplasty technically easier. Less scar tissue and soft tissue damage are present at the future surgical site, making the approach and dissection easier than if a formal ORIF had been performed. Additionally, reduction and stabilization of the fracture facilitate proper arthroplasty component positioning and fixation.

Disadvantages of minimally invasive fixation include limited access to the fracture site that leads to decreased ability to accurately anatomically reduce the fracture and apply stable hardware. Screw purchase in osteoporotic bone is unpredictable and it is technically challenging with safe zones for screw placement being small and complications from errant screw placement severe and life threatening.

Despite the inability to achieve anatomic reduction with this technique in most cases, several series have reported that elderly patients may tolerate poor reductions better than their younger counterparts. Additionally, if malreduction leads to osteoarthritis, total hip arthroplasty remains a viable option in the elderly age group, which may not be an acceptable option in a younger patient. Most series to date have demonstrated equivalent outcomes with percutaneous fixation and open reduction with internal fixation; however, the authors note a large bias in patient selection for each type of procedure.

Conventional open reduction with internal fixation

ORIF remains standard care for most displaced acetabular fractures in the elderly. In most cases, it allows for direct fracture visualization and anatomic restoration of the joint surface that is a key factor for future prognosis. This is best achieved through a single, nonextensile approach in the elderly. Combined and extensile approaches should be avoided in this age group, because they have been associated with longer operative times and higher rates of complications. However, occasionally they must be used to address displaced or comminuted articular fragments that cannot be otherwise addressed from a single, nonextensile approach.

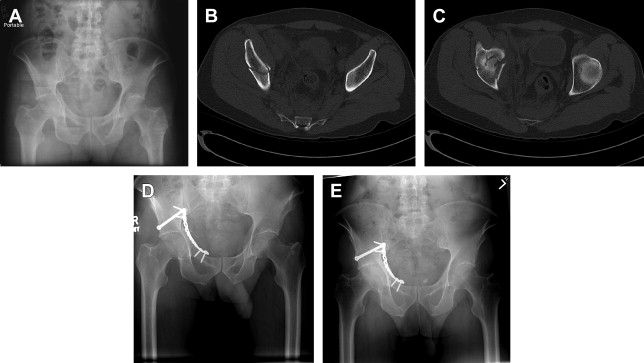

For injuries involving posterior acetabulum or posterior column, a Kocher-Langenbeck approach is recommended. For those involving the anterior acetabulum or anterior column, an ilioinguinal approach is recommended. For fractures involving both columns, an anterior or posterior approach is selected based on the acetabular column with the greatest displacement. The ilioinguinal approach has been the most widely used to address fractures of the quadrilateral plate. However, a Stoppa approach or posterior-based approach may be considered based on certain fracture characteristics ( Fig. 1 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree