Working with parents

Today, therapists recognise the importance of working with the parents of each child and for some time home programmes have been shown to them (Collis l947; Finnie 1997; among others). This chapter emphasises client-centred or person-centred therapy and learning (Rogers 1983), which may not be used by professionals who devise home programmes for parents. A more person-centred view presenting home programmes is given in a book for carers and parents of children with multiple disabilities (Levitt 1994).

King et al. (1997) and Rosenbaum (2004), in their many studies of the wishes of parents of children with disabilities, found that parental involvement in decisions about their child lowers stress levels and improves parents’ mental health. This was the top priority of the parents’ list of what they wanted from a service. This chapter conveys a belief that this also applies to parent participation in therapy programmes.

In the last 21 years, I have been developing a practical style of working which involves a child along with his parents in a collaborative learning experience with a physiotherapist. All share responsibility in assessments, therapy plans, methods and evaluations (Levitt & Goldschmied 1990; Levitt 1991b, 1999: 153–155). Ross and Thomson (1993) have recommended this specific collaborative approach (outlined in Levitt & Goldschmied 1990) following their studies on the evaluation of parents’ involvement in physiotherapy. Piggot et al. (2003) also find this approach of interest in their qualitative research project on parental adjustment and participation in home therapy.

This collaborative learning approach is a creative learning process, not only for a child and his parents but also for any therapist. The therapist learns what the hopes and expectations of a child and his parents are and what they already know and can do. Using these resources, therapists are better able to draw on their technical expertise for a more relevant programme. The respect and trust given to what parents and child already understand and can manage develops their confidence. More positive relationships grow between parents, child and therapist. There is more motivation as parents and child respond positively to a therapist who appreciates their desires and their ideas for solving some of their own problems.

The idea of joint goal setting and involving the parents and child in the shared decision-making process fits well with the United Kingdom’s National Service Framework for disabled children and young people with complex health needs (Department of Health and Department for Education and Skills 2004).

Odman et al. (2007) carefully studied parents’ perceptions of the service quality of two training programmes for a range of severity in children with cerebral palsy. Most parents were ‘influenced by high service quality rather than by perceived functional improvements’. The researchers used a measure (given in the appendix to their volume). This measure, ‘Patient Perspective on Care and Rehabilitation Process’ (POCR), was slightly adapted and has seven dimensions of the needs of the parent or child. Experience with the collaborative learning approach has shown substantial agreement with many of the findings of Odman et al. (2007).

Collaboration with other adults

When considering parents as adult learners, it is useful to draw on the studies of Rogers (1983, 2003, recent books following his many writings since the 1960s), Knowles (1984) and others in adult education. Rogers developed his ideas on human behaviour and the process of learning from studies of adults in psychotherapy. Rogers and Knowles applied ‘whole-person’ learning, together with other studies, to adult education. Similar concepts underlie the collaborative learning model developed from practical teaching experience not only for parents but also for other adults such as family members, other professionals and carers assisting a child’s development. This approach is also relevant to older people with disabilities (Chapter 7). The therapist will grow both professionally and personally as she or he learns and takes into account the knowledge, priorities and preferred learning style of these adults. A therapist becomes better able to select and devise methods to suit individual adults involved with a child. She or he also gains information from adults about various environments and cultures in which a child needs to function.

When family members and carers assist with the therapy programme in the way that parents wish, time needs to be given for them to become familiar with these programmes to maximise the child’s potential. This inclusive team approach facilitates both parents’ and family’s participation and helps them feel of value to their child with cerebral palsy. However, some family members may find working with their child stressful and prefer to give their personal strength to support the parents and child emotionally.

Family members also need support from therapists whether they participate or not in therapy programmes. The well-being of families positively affects the development of their child. Therapists need to listen respectfully to their views and concerns and promote their education about therapy.

Consideration must also be given to the fact that babies and young children with disabilities prefer being handled by one or two adults as they have to relate to an adult and adapt to different ways of being handled. No two adults are precisely the same in their touch, speed of ‘hands-on’ therapy and manual guidance. This is particularly relevant to those babies and young children who experience many unexpected spasms, uncontrolled reflexes and unreliable control of their posture and movements.

The therapists themselves are assisted and supported by other members of their team such as psychologists, social workers and paediatricians who work specifically with the families in ‘family-centred care’. Family-centred care has broadened from being child-centred to include not only the child but also the practical and psycho-social needs of parents and families. As services have evolved for children with cerebral palsy, the concept of family-centred care has become central to service provision. A number of research studies on family-centred care by Rosen-baum et al. (1998), King et al. (1997, 1999), Larsson (2000) and Odman et al. (2007) give evidence of increased satisfaction with services with lower stress levels and better mental health.

It is reassuring that family-centred care continues to grow in physiotherapy. However, the collaborative learning approach differs from various models in that it emphasises that learning processes are involved not only in ‘changing function of a disabled person’s body but also in changing ideas, behaviour and attitudes’ (Levitt & Goldschmied 1990). The person with disability and his or her family members and carers are changing as they embrace new ideas, new attitudes and behaviour as well as alternative ways of solving problems. Therapists also become learners as they deepen their understanding, gain new ideas, change any of their attitudes and give up old assumptions. A person’s willingness to change is facilitated by desires to learn, achieve more and feel more satisfaction in daily life. It is the quality of rapport between a therapist and a disabled person and her or his family that is fundamental during mutual learning experiences in collaborative work.

This chapter focuses in a practical way on the role of therapists working with children, older people, their parents and families.

Family cultures

Family-centred care needs to be culturally competent in order to be sensitive to different cultural values of families. Therapists can be culturally aware but not culturally competent. Cultural differences are not right or wrong regarding the ways families adapt, cope and develop their own strengths in living with a child with a disability. Non-judgmental listening, avoidance of direct questions which may offend and a genuine interest in a child’s family are needed even more than for families a therapist is familiar with in her or his own culture. There may also be a need for an English interpreter with positive attitudes to disability.

We are aware that families in our own culture do not all bring up their children in exactly the same way. In our multicultural societies, therapists are faced with more diverse cultural differences in their families. Diverse cultural backgrounds can provide challenges for the professional in terms of communication of functional techniques and appropriateness of the tasks given. For example, a therapist can learn from a Muslim family that a mother cannot be in a pool with her child during a swimming session unless the pool has a ‘women only’ time as this would be prohibitive for her. Special bath chairs and other equipment may not be appropriate for some parenting customs and a special chair may not be relevant to floor sitting used socially in a particular culture.

Normal motor developmental patterns differ in different cultures (Chapter 9). Lying on the floor or crawling may not be welcomed. Some consider floor work in the home as unhygienic. Some families do not expect play activities used for ‘medical treatment’ or child developmental guidance. Creative adaptations to familiar child rearing methods need to be made. In other situations, communication of unfamiliar methods does not need much verbalisation in parents’ own language, as physical methods are demonstrated, pointing out immediate positive abilities revealed in a child or perhaps in another child similar to the child being treated. Parent–child groups are helpful as some mothers show willingness to try methods which inspire those more hesitant.

Therapists need to have a general practical knowledge of different cultural groups with whom they are involved. This can include likely health beliefs, religious practices and social customs. However, the collaborative learning approach offers therapists a direct working knowledge of the customs of individual parents and families (Levitt 1999). This approach for individuals avoids stereotyping a child, parent or family as being the same as all families in the cultural group. This stereotyping is less likely to happen when therapists are willing to learn from the individual older children, parents and family. A qualitative research study of physiotherapists’ perceptions in cross-cultural interactions by Lee et al. (2006) found that some participants did not recognise that they stereotyped ‘clients’ perceptions of pain, the desire for passive treatments, dependency on family members and male dominance in specific cultures’. This small study shows implications for the quality of physiotherapy.

The collaborative learning approach

A child and his parents are offered:

Opportunities to discover what they want to achieve.

Opportunities to discover what they want to achieve. Opportunities to clarify what is needed for these achievements.

Opportunities to clarify what is needed for these achievements. Opportunities to recognise what they already know and can do.

Opportunities to recognise what they already know and can do. Opportunities to find out what they still need to learn and do.

Opportunities to find out what they still need to learn and do. Participation in the selection and use of methods.

Participation in the selection and use of methods. Participation in the evaluation of progress.

Participation in the evaluation of progress.Genuine participation in all these aspects by child and parents helps them feel more committed to the programme of work. It gives them some sense of control which decreases many of their anxieties and builds their confidence. They become more able and more willing to absorb ideas, information and practical suggestions from therapists.

Parents and an older child are accustomed to being asked ‘What are your problems?’ or ‘What are your concerns?’ This may well decrease their confidence as to them it emphasises the impairments, sadness and inadequacies. A positive, hopeful introduction about what could be learned and achieved is preferable. For example, a therapist might say ‘Tell me what you would like to do better in your daily life’. More detail is given below.

The collaborative learning approach considers not only the views of parents and child but also the perspectives of therapists. There can be consensus and also different views between parents and therapists. Different views are managed by negotiation for an option both find acceptable. There can be a mutual understanding that there are different paths to the same common goal, which is carefully stated in the words of the parents. Early in the growing quality of the relationship, a professional can concede to follow the parents’ choice until the relationship is strong (see also ‘Participation in the selection and use of methods’ below).

This style of work with parents coincidentally tunes in with the views of Bailey and Simeonsson (1988) in the field of developmental disabilities and that of Larsson (2000) among others. Bailey and Simeonsson found in their many studies that parents and families want the following:

Education and information.

Education and information. Parental training in skills to help their child.

Parental training in skills to help their child. Emotional support.

Emotional support.This collaborative learning approach takes account of all these aspects. The studies of Sluijs et al. (1993) call for more education of patients by their physiotherapists and this approach offers a response to this as well by being more family-centred (Levitt 1991b). A pilot study by Ahl et al. (2005) found that parents’ expectations were of a functional training approach in daily life settings. When such a programme was used, parents’ perceptions of the rehabilitation process were enhanced. The collaborative learning approach focuses on parents’ and child’s choice of daily life functions (Levitt and Goldschmied 1990). Jahnsen et al. (2003) in their review of studies on parental experience with physiotherapy quote a number of studies which support many aspects of this approach and find positive responses in parents.

Opportunities to discover what parents and child want to achieve

Many parents are quick to say what their expectations from therapy are. Others want time to discuss this with their families. Some parents are unaccustomed to asserting what they want as they have anxieties and ‘learned helplessness’ (Greer & Wethered 1984; Seligman 1992). They may also not wish to upset their specialised therapist as they wrongly or rightly sense this might be so if they choose what therapy might focus on for their lives. Avoid using direct questions (which feature in some parent questionnaires) as this may feel like an uncomfortable confrontation with their many needs.

The therapist gains their trust by inviting them to talk about a typical day in their lives by saying which daily activities they would like to improve further and which daily activities are most stressful or time-consuming. These may be the same or different activities such as a child’s feeding, washing, dressing, toileting, playing and a child going from place to place at home, school or in other environments. The therapist prompts parents and child to think about these activities as they are familiar to them. She explains that if she knows about their daily activities then she can plan a more relevant therapy programme with them. She also tells them that she can then clarify what she can offer from her profession for their wishes. If a child cannot communicate what he would like to achieve or do better, then he is observed to see what interests him. He may enjoy bath time, mealtime or special times for play with his parents. In a more specific situation, if possible in his familiar environment, a baby, child or a severely disabled individual at an early stage of development has facial expressions of pleasure and body language that can easily be observed, such as wanting to touch a person they like or a toy of interest. Their pathological symptoms may be used to show pleasure or displeasure, such as extensor thrusts or increasing involuntary motions.

It is essential to start with the priorities of child and parents rather than set aims or goals for them. Even if we set goals and then ask for their agreement, we are really setting the goals. This does not enable them to discover their own aims, formulate their own expectations and so improve their ability to share their ideas and feel more confident. Once parent or child states their wishes, the therapist repeats what they have said with a check such as ‘Have I got that right?’ This places parents and child in a more independent position. It is necessary to acknowledge when a child’s wants differ from a parents’ wants.

In their study on the values of activities of daily living in stroke patients with hemiplegia, Chiou and Burnett (1985) compared the choices of these patients with the choices made by their therapists. It was found that in 29 therapist–patient pairs, only one pair showed similar views regarding specific values placed on the daily activities. We need to recognise that professionals with clinical wisdom and experience do know what is needed for parents or patients, but do not really know what is needed for particular parents or patients at specific times. This leads to frustration on the part of both therapists and their recipients. Physiotherapists often say ‘they [parents] do not really understand our aims’ (Levitt 1986, 1991a). This is despite technical explanations clearly given by a therapist. It is the connection or marrying of a therapist’s ‘goals’ with an individual’s ‘goals’ that matters to facilitate mutual understanding.

Opportunities to clarify what is needed for these achievements, to recognise what they already know and can do and to find out what they still need to learn and do

These opportunities are given in the following ways:

A therapist needs to continue her studies on task analyses in different types and degrees of severity in cerebral palsy so that she draws attention to the most successful components of functions (tasks) in each child. Parents are also learning from a therapist how to break down their chosen task into components needed for their own child. This is one of the ways that can be used to assist in solving a motor problem of a child. Each parent will have their own pace of learning this task analysis.

Although the therapist is also observing obvious impairments such as hypertonus, weakness, involuntary motion or deformities, these are not yet stated in these words. Her comments on such problems relate to ‘what needs to be learned’ such as a child ‘still needs to stretch an elbow more’ or ‘still needs to learn how to sit more steadily’ or ‘how to stand up really tall’. This is a more motivating style.

Once child and parents show what they can do, the therapist validates their achievement and shares their pleasure. She might say something like ‘That is good, and it could be even better if we try the following suggestions’. She can then demonstrate additional positioning, modification of the physical environment, appropriate manual support, handling or physical guidance to reveal more of their abilities and functions. As parents and child have had their capabilities acknowledged by a therapist, they are more willing to listen to what this therapist adds to the programme.

Task or functional analyses. The task analyses are also outlined in Chapter 6 about a child learning motor function. Analyses of components of a child’s function are also given in Chapter 9, which outlines details of developmental functions, some of which are more detailed for therapists rather than for most parents. The motor learning models give more small achievable steps which are more clearly observed by parents and family members. This can show what has been achieved, no matter how minimal, for example, in a sequence of components, such as rising from a chair to standing. There are sequences of actions in activities such as feeding, washing and dressing which can be seen in small achievable steps, some of which may have already been achieved to show a baseline of abilities. This allows parents and child to experience initial success. This is a particularly encouraging way of looking at tasks to be learned and counters feelings in parents or child of ‘I’ll never do this!’ There is also a hopeful future that additional components and perhaps the full function will develop.

Once parents and child have stated their wants, these are analysed into steps. Steps or components towards parents’ functional wishes are usually termed ‘goals’ because they are expected in a short time. Goals are clearly defined, apply to daily lives and once again checked that parents feel they know the goals and can achieve them at home. Goals are usually given by professionals (termed ‘sub-skills’ in the study by Ahl et al. 2005). However, this collaborative learning model enables parents to learn general task analyses so that short-term goals are jointly created with therapists. Facilitation interviews are used for parents who need extra support to create goals.

The therapist’s specialised assessment. Once the motor and sensory components of a task have been observed by a therapist within a whole task, she decides how much more she needs to assess. She can then carry out more detailed assessments of components of the task and impairments of muscle work, joint ranges and tone, abnormal postures and other sensorimotor details. However, the advantage of first seeing all these separate aspects within a whole task reveals many ideas which challenge the accuracy of only using separate examinations of impairments or motor components (motor abilities, prerequisites) to plan physiotherapy home programmes.

The tasks or daily functions have been chosen by the parent or child and are thus being performed by motivated persons. Results of such an assessment tend to be more positive. There is interaction between all aspects of a task, so ability in one component activates any residual ability in another component. In my experience, tests of reflexes may be abnormal if carried out in isolation, but if observed within the context of parent–child interactions during daily activities, the assessment shows a more positive result. For example, a grasp reflex may become immediately modified as a baby places her hand on her mother’s breast during feeding; an asymmetrical tonic neck response or a Moro reaction is modified or overcome as a child puts both her arms around her father’s neck or holds her head up in eye-to-eye contact during social and specific daily activities (Levitt 1986).

Participation in the selection and use of methods

There is no sharp division between the assessments just described and methods. As mentioned above, a therapist’s assessment methods of positioning, physical guidance and amount of manual support reveal more of a child’s abilities and function. These methods then serve as treatment methods and are extended to include equipment, orthoses, furniture, footwear and playthings. It depends on the severity of the cerebral palsy together with the views of the parents, child or older person as to the content of the therapy programme.

As with a child, a parent is first observed practising his or her method of training his or her child and then guided physically or verbally by the therapist as they carry this out. This allows them to improve their method. Details are added according to what each parent can absorb and manage. Once their own style of parenting and handling is used, some parents welcome additional methods from therapists. Each parent also has their own pace of learning and some need many more repetitions of a method than others. Videos of methods with the child can be taken home for reviewing what parents have learned with their therapist and to show to their family. One parent may make notes or list exercises in their own words, whilst the other carries them out with the therapist.

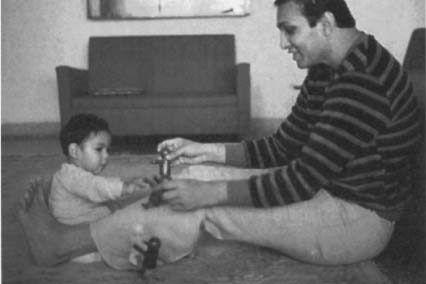

As parents and child develop their confidence, they will share their own ideas with their therapist (Fig. 2.1). She always welcomes their ideas as they are showing an eagerness to take some responsibility in the programme and not become totally dependent on her. The therapist considers their suggestions, and if inappropriate, modifies them or shelves them for a later stage in a child’s development. With any validation of the ideas of parents or child they become more able to cope with times when some of their ideas are incorrect. As parents have been learning and gaining information on their child’s condition within a positive relationship, there can be negotiation on which methods are suitable. Clearly a therapist needs to become more flexible so she can be open to what parents and child offer. This means that she cannot stick rigidly to any system of therapy. The therapist also needs to learn what is realistic in the parents’, carers’ and child’s daily life. This includes cultural considerations, time constraints and a child’s general health as well as the physical environment.

Figure 2.1 There is pleasurable interaction between this father and his child as the child’s postural control with hand function is being developed. Father chose to use his feet to assist his child in symmetrical weight bearing on hips and weight shifting from side to side or forwards and backwards during play.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree