2 A biological basis

Skin

The first thing to be noticed by the massage student when touching the skin is that it is usually soft and, in most parts of the body, smooth. This top outer layer which can be touched is the epidermis, the epithelium of the skin. It consists of keratinised, stratified, squamous epithelium which is arranged in five laminae according to their cell type (Fig. 2.1). These five layers are arranged in two zones: the deeper is known as the zona germinativa, a single layer of columnar cells, and the more superficial zone is the stratum basale. Terminology, however, varies between anatomists and biologists (Thibodeau & Patton 2007). Cells are continuously being lost from the surface and replaced from the deeper layer.

Figure 2.1 • Layers of the skin and circulatory plexi.

Reproduced, with permission, from Holey (1995). Originally published in Schuh I 1994 Bindegewebsmassage. Fischer-Verlag, Stuttgart.

This natural process occurs constantly, but certain events will speed it up. Friction on the skin, for example, caused by the clothes when dressing or during massage, results in desquamation. Massage will often remove the top layer (stratum corneum), which is readily replaced. This occurs when skin may be seen to ‘rub off’ or may be left on the treatment plinth following treatment. This is a normal and painless process. It tends to be excessive if the skin is very dry or visibly flaky (following removal of a plaster cast, for example) and can be reduced by the application of an oil-based lubricant. In severe cases, a soap and oil solution is particularly beneficial. The epidermal cells become gradually flatter and more keratinised as they move to the surface—more than 90% of epidermal cells are keratinocytes (Thibodeau & Patton 2007). Keratin, a protein, is important for hydration of the skin. Dry skin has reduced water content and the keratin allows swelling when the skin is wet. This is useful information to have when selecting the appropriate media for massage: the choice of oils, creams or talcs should be based not only on the type and purpose of massage but also on the individual skin quality. Keratin provides protection, and skin that has been soaked and has a whitened, wrinkled appearance should not be massaged as the effects of treatment on the superficial layer will be difficult to predict and monitor.

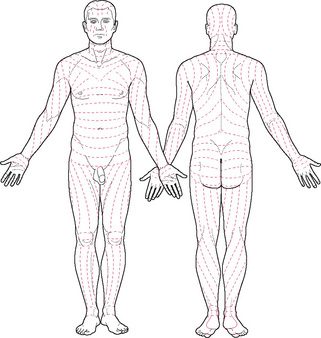

The reticular layer contains mainly thick collagen fibres (for strength) interspersed with reticular and elastin fibres (the latter for stretch and pliability) which form a tough interwoven layer. The directional lay of the skin in different parts of the body results from some of these fibres lying parallel to the skin surface. Skin is always under tension and the lines along which this tension lies are known as Langer’s or Kraissl’s lines (Fig. 2.2). They are important because they dictate the natural variation in tension when the skin resists movement and when it heals. If a cut in the skin follows the tension lines, scarring will be minimal as there will be minimal stress on the wound—an important principle utilised by surgeons. The fibroblast cells (which secrete the precursor for collagen) and phagocytes, important in immune defence mechanisms, are found in this layer.

Figure 2.2 • Tension lines of the skin.

Reprinted from Anatomy: regional and applied, Last (1984), with permission from Elsevier.

Circulation in the skin

Blood vessels within skin are found lying in and running between three flat horizontal plexi, as shown in Figure 2.1. Here, it can be seen that small arteries pierce the superficial fascia and form a horizontal plexus known as the rete cutaneum at the interface between the dermis and superficial fascia. It gives off vessels to supply the adipose tissue, glands and follicles. Some vessels reach the junction between the reticular and papillary layers of the dermis where they form another flat plexus, the rete subpapillare or superficial plexus. From here, capillaries supply the dermal papillae before travelling back to the venous plexus immediately below the superficial plexus, draining into the flat intermediate plexus in the middle of the reticular layer of the dermis which connects to the deep laminar venous plexus at the dermis–superficial fascia junction.

As the vessels tend to lie in plexi at the different interfaces of skin, movement in the form of manipulation between layers will influence the circulation. Capillaries running through the layers will be similarly influenced by gross movements of the tissue as a whole. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

Innervation of the skin

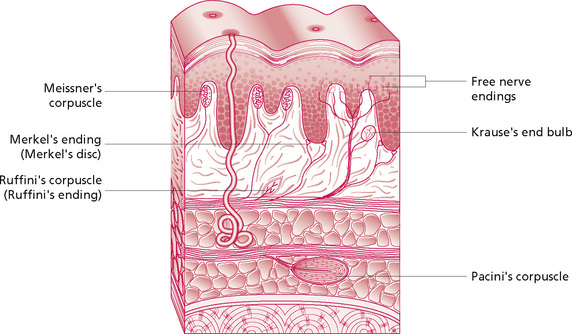

• Merkel discs which respond to shear forces and vertical pressure: this stimuli is magnified by hair follicles and structural ridges grouped into Iggo dome receptors, on the underside of the epithelium;

• Meissner’s corpuscles, found in the dermal papillae: these are rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors which are responsive to mechanical deformation;

• Pacinian corpuscles in the deeper layers of the skin and superficial and deep fascia: they are innervated by a single axon only, and respond to a narrow range of vibration frequencies and rapid changes within the tissues; and

• Ruffini’s corpuscles in the deeper dermis and hypodermis respond to stretch: they have an important tactile function.

The endings show specificity as a result of their differential sensitivities, and interpretation of the modality of sensation is due to the location of their termination in the brain. The endings listed above are those which have most relevance to massage. They are stimulated by mechanical deformation which stretches the membrane, thus opening the channels through which ions pass to depolarise the nerve fibre. The Meissner’s corpuscle consists of a central nerve fibre surrounded by terminal nerve filaments within an elongated capsule. The construction of the Pacinian corpuscle consists of a central nerve fibre surrounded by capsular layers (Fig. 2.3). The fibre is distorted in various ways by compression of any part of the capsule. The fluid in the corpuscle immediately redistributes so that the deformation is no longer transmitted to the central fibre until the force is removed. Thus, repetitive forces rather than continuous ones will affect the nervous system more strongly; this demonstrates the importance of the continuous movement in massage.