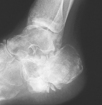

A 36-year-old window cleaner presents, having slipped 20 feet off a ladder. He landed awkwardly on his left heel, which immediately became extremely swollen. In casualty a radiograph confirmed that he had fractured his calcaneus (Fig. 54.1).

1 What is the most common mechanism of injury and what other fractures might have been sustained when the patient fell?

2 How are calcaneal fractures classified? What methods might be used to ascertain the exact type of injury?

3 What treatment is appropriate for this patient?

4 Will the long-term prognosis be favourable?

|

| Fig. 54.1 |

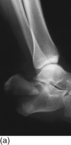

Fracture of the calcaneus

1 Most frequently patients land on a pronated foot, destroying their medial longitudinal arch and forcing the heel into valgus. The peroneal tendons will generally be held in their groove on an intact lateral wall. Vertical shear force will produce an initial fracture line (described by Palmer; Fig. 54.2), splitting the bone into two parts: an anteromedial fragment including the sustentaculum tali and a posterolateral fragment including the calcaneal tuberosity. Further fractures propagate according to the force and exact direction of injury.

Calcaneal fractures are bilateral in 5–10% of patients, associated with other lower limb fractures in up to 25% and with a lumbar spinal fracture in 10%.

2 In terms of future disability, fractures with an intra-articular extension will generally have a poorer prognosis than those that do not. Calcaneal fractures are no exception and early radiological classifications (by Böhler and Essex-Lopresti) subdivided the fracture types into two primary groups, according to whether the posterior subtalar articular surface was involved.

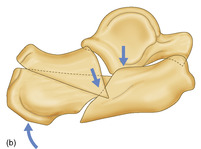

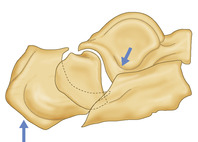

Transarticular fractures are less easily classified. Essex-Lopresti considered two primary subgroups. In the first type a downward force causes heel eversion at the subtalar joint and a ‘tongue-type’ fracture (Fig. 54.3). In the second, a shear force typically fractures off the sustentaculum tali, depressing the centrolateral articular segment into the calcaneal body, as shown in Fig. 54.1 and Fig. 54.4. This classification was further refined by Sanders et al in 1990 based on the number and location of the articular fracture fragments on a coronal CT (Fig. 54.5).

3 Heel fractures are invariably accompanied by massive soft tissue contusion, and immediate high elevation of the injured foot is essential (Fig. 54.6). In this case, the patient’s fracture was also extremely comminuted and it was felt that the joint surface was destroyed beyond salvage. However, as noted on the CT image, the heel was excessively splayed. A closed manipulation was performed under general anaesthetic, once the initial swelling was down, and a well-padded plaster cast applied. After a further period as an inpatient with his foot elevated, the patient was allowed to mobilize on crutches without weightbearing. The cast was retained for 6 weeks. Despite intensive physiotherapy during the next 3 months the joint progressively ankylosed (Fig. 54.7).

If surgery had been possible, then the essence of treatment would have been to realign the subtalar joint, restoring Böhler’s calcaneal-tuber joint angle (the angle between the superior surfaces of the calcaneus) to that of the opposite foot (normal range 25–40°). A tongue-type fracture may simply be displaced back into position using a lever, sometimes termed a Gissane spike, inserted posteriorly into the bone. The fracture can be held with a couple of screws or staples (Fig. 54.8).

Open reduction and fixation is generally required for joint depression fractures. Often bone grafts must be inserted to buttress the joint and the fracture is then usually held by a plate (Fig. 54.9).

4 Rehabilitation after a calcaneal fracture is prolonged and the average time off work for patients in most reported series is about 6 months. Function is impaired by any ankle, subtalar or midtarsal joint stiffness.

Heel cushioning may help relieve pain caused by disruption of the heel fat pad, but if bone spurs on the sole or lateral calcaneal wall cause localized pressure or tendon impingement respectively, then bone resection may be necessary. A few patients, such as the one illustrated, will still complain of unremitting pain 12 months after injury. A formal subtalar fusion may then be the only option.

|

| Fig. 54.2 |

|

|

| Fig. 54.3 |

|

| Fig. 54.4 |

|

| Fig. 54.7 |

|

| Fig. 54.9 |

Key points

• Bruising on the inner aspect of the sole suggests a heel fracture: ‘the Oxford sign’.

• High elevation of the foot will lessen initial discomfort.

• Restoration of subtalar joint congruity is the key to a good clinical outcome.

• Bone grafting may be required to buttress the joint surface.

• Physiotherapy is essential to prevent stiffness.

Further reading

Bridgman, SA; Dunn, KM; McBride, DJ; Richards, PJ, Interventions for treating calcaneal fractures, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Issue 4) (1999).

Essex-Lopresti, P, The mechanism, reduction technique and results in fractures of the os calcis, British Journal of Surgery 39 (1952) 395–419.

Magnan, B; Bortolazzi, R; Marangon, A; Marino, M; Dall’Oca, C; Bartolozzi, P, External fixation for displaced intra-articular fractures of the calcaneum, Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 88-B (2006) 1474; 9.

Sanders, R, Current concepts review – displaced intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus, Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 82 (2000) 225; 50.

Stephenson, JR, Treatment of displaced intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus using medial and lateral approaches, internal fixation and early motion, Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 69-A (1987) 115; 30.

Case 55

Despite braking as hard as possible, a 22-year-old student was unable to prevent his Alfa Romeo crashing at speed into an oncoming car. He suffered the compound fracture shown in Figure 55.1.

1 What exactly has caused this injury?

2 Who described these injuries and what type would this be?

3 Is subchondral bone atrophy significant? When is avascular necrosis likely to be evident?

4 Would there be merit in any form of hindfoot arthrodesis? If so, which and when?

|

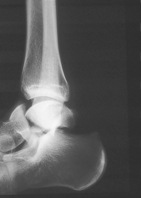

| Fig. 55.1 |

Fracture dislocations of the talus

1 It was always assumed that talar neck fractures were caused by the leading edge of the tibia striking the talus when the foot was excessively and forcibly dorsiflexed. Cadaveric modelling, however, suggests that it is more likely that it is simply the midfoot which is hyperextended on the talus, when the leg and foot are outstretched, i.e. the hindfoot is held rigid by a taut Achilles tendon. Such a position typically occurs in a ‘head-on’ motor vehicle accident when the foot is pushed upwards by the pedals or, as originally described, by a similar mechanism in a light aircraft crash, ‘the aviator’s fracture’. Recently, a boy of 9 years was admitted after sledging backwards (Fig. 55.2).

2 Hawkins classified injuries of the talar neck into three groups: type I, undisplaced talar neck fracture; type II, fracture of the talus with subluxation of the subtalar joint; type III, fracture of the talus with dislocation of the bone from both the subtalar and ankle joints. A fourth type has since been added to take into account any associated subluxation or dislocation of the talar head off the navicular bone.

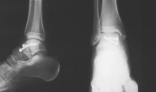

The 22-year-old patient described suffered a type II injury. He was treated by wound debridement and stabilization of the fracture with two lagged cortical screws (Fig. 55.3).

3 Although fracture malunion can occur, leading to impingement of the dorsal bone surface on the margin of the distal tibia on dorsiflexion, we have found that the protuberant lip of bone is generally resectable and patients regain normal foot function. In stark contrast, avascular necrosis develops slowly and it may be up to 2 years before the condition becomes clinically evident. Avascular necrosis occurs in up to 50% of type II injuries, however treated. Subchondral bone atrophy (Hawkins’ sign), seen approximately 6 weeks after a talar fracture is said to be a good prognostic indicator. The sign is probably a reflection of increased localized bone vascularity and healing (Fig. 55.4).

4 Once avascular necrosis sets in, or if there is significant articular damage to either the subtalar or ankle joints, then further surgery is generally required. Unfortunately, the loss of talar height will mitigate against a successful single joint arthrodesis. Pantalar hindfoot arthrodesis may be the only viable option and some leg length discrepancy from shortening is an inevitable result. Most trauma surgeons would not consider astragalectomy (talus excision).

|

|

| Fig. 55.2 |

|

| Fig. 55.3 |

Key Points

• Avascular necrosis may not be evident for up to 2 years.

• Hawkins’ sign indicates a favourable prognosis.

Further reading

Hawkins, L, Fractures of the neck of the talus, Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 52-A (1970) 991–1002;

Lindvall, E; Haidukewych, G; DiPasquale, T; Herscovici, D; Sanders, R, Open reduction and stable fixation of isolated, displaced talar neck and body fractures, Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 86-A (2004) 2229; 34.

Metzger, MJ; Levin, JS; Clancy, JT, Talar neck fractures and rates of avascular necrosis, Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery 38 (1999) 154; 62.

Case 56

This 58-year-old women presents with a 6-week history of dull aching pain in the forefoot experienced on prolonged weight-bearing; she denies any injury to her foot. She is diffusely tender across her forefoot and there is a tender swelling over her metatarsals. An AP radiograph is shown in Figure 56.1.

1 What is her diagnosis and what is the cause of this ‘injury’?

2 What are the risk factors for this condition in middle-aged women?

3 How should her injury be treated?

4 Why are radiographs of limited value in the diagnosis of this condition?

5 What other investigation(s) can be used?

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|