CHAPTER 8. Introduction to bodywork

8.1. Assessment of the maternity client

Introduction

It is important for the therapist to make an appropriate assessment for the maternity client in order to know the most effective treatment plan and to understand the few cases where work would not be appropriate. Many therapists use the SOAP charting procedure (Thompson 2002) – formulating Subjective (S) (client perceptions) Objective (O) (therapists findings) Assessment (A) into the (Treatment) Plan (P). The maternity assessment will include understanding the relevance of existing assessment skills and awareness of any modifications to the assessment which need to be made.

Assessment procedure

Depending on their training and skill set, the bodyworker will have variations in emphasis in their intake/assessment. Common components include:

Observation/visual assessment

Visual assessment should begin with the first moment of contact. This may begin before the client has even crossed the doorway into the therapy room. How is the client carrying herself in her pregnancy? How is she holding the newborn? How does she approach the therapist, both in her demeanour and her mobility? What does her face express?

Some therapists prefer to keep the visual assessment informal and simply observe the client’s posture while others conduct a more formal postural assessment including use of a plumb-line and specific orthopaedic tests. Another option is to observe clients while they are carrying out any suggested exercises.

It is important to understand the common postural patterning of the maternity client in order to guide and inform specific tests. This understanding will also inform the therapist regarding the appropriateness of exercises.

In Chinese medicine this aspect of the assessment is called Bo shin and includes observation of the colour of the skin and the tongue. In pregnancy there is a greater circulating blood volume, the core body temperature is higher and there are various changes in the skin. Understanding thoroughly how the body changes will influence this aspect of the assessment and the therapist’s ability to determine effective ways of treatment.

Listening and questioning

Filling in the health history form forms a significant part of this aspect of assessment. The form which is used for the non-maternity client may well be inappropriate both in its inclusion and exclusion of certain questions. Understanding the potential emotional as well as physical changes of the maternity period will help guide the therapist in determining appropriate questions to ask in order to elicit relevant information.

In Chinese medicine these are two distinct assessment categories. Bun shin is the listening aspect which includes listening to the type of sound and tone of the voice and how the client is talking rather than specifically what they are saying. It also includes the use of smell, as specific body odours relate to expressions of different organ energies.

The second assessment category is Mon-shin – questioning which would include more specific information gathered verbally from the client.

Touch/palpation

This may occur as part of the postural assessment and during specific orthopaedic tests. For some therapists it may include pulse or Hara (abdomen) and back energy assessment. However, the client is also being continually assessed during the treatment. As the therapist touches the tissues of muscle, ligaments, and the joints of the body, as well as contacting lymph and the pulses, and different types of energy, their work is constantly being informed. Again, understanding how the body changes will affect the understanding of this information. The Chinese referred to this aspect of assessment as: Setsu shin.

The maternity health history form: modifications

For most therapists, the form that is used for non-maternity clients is incomplete with respect to obtaining comprehensive information. For example on many forms pregnancy is listed as a ‘condition’ or even a ‘caution’ or ‘contraindication’ for bodywork. Furthermore, common case history questions are not specific enough to elicit the kind of information which is needed in order to work safely and effectively with this population group.

Taking a good health history provides the basis for assessment and treatment decisions. However, sensitivity is needed in eliciting appropriate information. Asking open questions may be the most non-invasive way to receive information. For example, it may be inappropriate to ask directly if the client has had a previous miscarriage (spontaneous abortion) but by asking if they have had previous pregnancies the possibility is opened up for the client to share information about any pregnancy losses she has experienced. It may not seem appropriate to ask direct questions about the woman’s partner, since she may not be in a relationship, but the therapist can ask whether the woman has people who can provide support to her.

The therapist should be aware that some questions may be construed as invasive or irrelevant for the client. The ability to connect with a new client and good communication skills are essential when asking potentially challenging questions. Ensure clients are able to refrain from responding if they so choose. The therapist may also need to explain why they are asking specific questions and their relevance to the session. The client’s right to privacy as well as confidentiality must be underscored.

As each bodyworker has different needs for their health history form, we have focused on general items that the therapist might consider including with their own form. These items are in addition to the information which is gathered with non-maternity clients. General information gathered for any client such as previous health history issues, injuries or medical conditions, lifestyle factors, and goals of the treatment are obviously also relevant for the maternity client.

Common abbreviations in clinical notes

In some countries the woman may carry her clinical care notes from her primary care provider. She may willingly share this information with her therapist. Common abbreviations used in clinical notes are:

Para 0 – no previous birth

Para 1 or 2 – 1 or 2 previous births

Para 2+1 – 2 previous births plus a miscarriage before 28 weeks

LMP – last menstrual period

EDC/EDB/EDD – expected date of confinement/birth/delivery

Alb – albumin in urine (protein). This may be a sign of pre-eclampsia

Hb – haemoglobin. If less than 10.5 considered anaemic

Hct – haematocrit: percentage of red blood cells. If less than 32% considered anaemic

Fe – iron

BP – blood pressure

FHT/R – fetal heart tones/rate

H/NH – usually refers to heart tones

Fundus – top of uterus

Cx – cervix

PP – presenting part of fetus

Vx/Vtx – vertex (head down)

Ceph – cephalic

LOA – left occiput anterior

LOP – left occiput posterior

LOT – left occiput transverse

ROA – right occiput anterior

ROP – right occiput posterior

ROT – right occiput transverse

RSA – right sacrum anterior; the most common breech presentation

Eng/E – engaged

T – term

The areas covered below may be included on the case history form or asked as additional questions.

Pregnancy history

• Menstrual history. A longer menstrual cycle may indicate a tendency for a longer pregnancy, a shorter cycle a shorter pregnancy; a history of heavy bleeding may indicate a tendency to bleed.

• History of previous pregnancies, length of gestation, any complications. This provides a foundation for possible issues or conditions which may be relevant for care in the current pregnancy.

• Was the pregnancy planned? This may elicit information about whether the pregnancy involved assisted reproduction.

• Gestational age/EDB. This is needed so the therapist knows what to expect in terms of possible symptoms, as well as positional and technique adaptations.

• Any issues in the current pregnancy history to date. This will help highlight key issues such as nausea, backache, fatigue, stress, etc.

• History of vaginal bleeding. This may or may not mean that bodywork is contraindicated depending when the bleeding commenced, how heavy it is, whether it is resolved, and so on. The cause of any bleeding in pregnancy should be assessed by the primary care provider before the therapist proceeds to do any treatments. Current bleeding would, in most cases, be a contraindication to bodywork (Box 8.1).

Box 8.1

Bleeding in maternity care

Active uterine bleeding: immediate referral; no bodywork

Any case of active uterine bleeding needs immediate medical attention. If the bleeding has settled, a detailed health history needs to be taken to establish the cause, if known, in order to determine appropriate work. Possible causes of bleeding are:

First trimester

• Implantation bleeding; if mild not necessarily an issue once settled.

• Threatened abortion/miscarriage. Once this has settled, if the fetus is still alive, then work may continue.

• Ectopic pregnancy or hydatidiform mole: immediate referral if active bleeding and once diagnosed the woman would receive appropriate medical treatment. Work can then be done to support the recovery process.

• Cervical lesions: once these have been assessed and there is no bleeding then work may continue.

• Vaginitis: again work may continue once the bleeding has settled.

Second and third trimesters

• Placenta praevia; may be from mild to severe; if no bleeding can work with modifications (see high-risk chapter)

• Placental abruption: may only present with mild bleeding, but is always a potential emergency, particularly if the pregnant woman shows signs of shock and a hard uterus.

Labour

• Placental detachment.

Postnatally

• Retained placenta.

• Placental issues.

• Infection.

Exception

Where there is bleeding but the woman knows she is miscarrying and that the fetus has died, and wants support in that process then it is her choice to receive bodywork.

• Abdominal pain. This will determine whether abdominal care will be included in the treatment – is the client suffering from overstretched skin, ligamentous discomfort, or experiencing more serious issues such as premature labour, placental issues or blood pressure problems (HELLP)? (See Box 9.2 and p. 254.)

• Problems with urination. Frequency or burning could indicate a urinary tract infection. Lack of urination may indicate a more serious complication which would require immediate referral.

• Groin pain or discomfort. Could indicate possible PGI/SPD.

• Blood pressure: current and previous history. Some therapists take the BP at the beginning and/or ending of the treatment. If not, the therapist needs to know when blood pressure was last taken, and whether it was within normal limits. Blood pressure is an important indicator of health in the maternity period.

• Varicose veins, leg cramping or pain, sensory loss (numbness). These kind of issues are fairly common and it is important to identify them in order to establish appropriate work to the legs.

• Clotting issues/suspected DVT. This is potentially an emergency situation and needs to be screened for. It is rare in healthy pregnant clients.

• Date of last visit to primary care provider. This will ensure that the client is receiving regular antenatal care, and inform the therapist of the type of care received whether midwife, obstetrician, or family physician.

• Position of baby (from week 28) if known. If it is not known then the therapist may feel it is appropriate to encourage the woman to be aware of her baby, ask if she is feeling movements, and perhaps elicit a discussion about how she feels about her pregnancy, her baby, birth, and so on.

• History of previous labours. This can indicate problems or anxieties which may affect the client in her current pregnancy. It can also provide useful information for the therapist who offers birth preparation work or who attends births.

• Birth plans for this labour. This is more appropriate to ask during the last trimester, unless it is relevant earlier. It opens the possibility of talking about bodywork as an option during the birthing process and potentially as a means of pain relief.

• History of the previous postnatal period. This is important to establish if there were any problems with postpartum depression, or issues adapting to motherhood or breastfeeding in order that preventative type of work may be done.

• Family information, e.g. how many other children, family support. This gives an idea of the kind of demands made on the client, for example if she is well supported, single or with partner and so on.

• Available support. This elicits further information about family set-up but also emphasises the need for support in pregnancy.

Labour support form

If a therapist is attending their client’s birth, there will be additional information that will need to be obtained both in advance of the birth and during the birthing process. Note taking during the delivery would be in alignment with the requirements of the therapist’s scope of practice. A post-birth debriefing session may also be included as part of client care.

Questions/information to be gathered include:

What are your hopes for this delivery?

Are there specific reasons for why you want a doula/birth support person for your birth?

What are your beliefs about birth? What sort of births did your mother/sister/close family members have? What was your own birth like? (This information gathers the kind of beliefs, conscious and unconscious, the woman may have about birth and also memories/imprinting of her own birth.)

Birth record:

Gestational age at delivery (in weeks)

Time labour contractions began

Time labour contractions were 5 mins apart

Dilatation/effacement/station when admitted to hospital if applicable

Spontaneous rupture of membranes? Yes/ No

If Yes, what time?

Place of rupture (home, hospital, car, other)

Dilatation, if known, at time of rupture

Colour of the amniotic fluid? Was meconium present? Yes/No Light/Moderate/Thick

What was the approximate length of first stage (0–10 cm)?

How did the mother feel during first stage? What kind of support did you offer? Bodywork given. Effect.

Second stage (bearing down)?

How did the mother feel during second stage? Positions. What kind of support did you offer? Bodywork given. Effect.

What was the approximate time/length of third stage (delivery of placenta)? Were there any third stage complications?

If yes, please explain

How were the mother and baby? Any support given?

Was the mother breastfeeding? Who helped her establish breastfeeding?

Any other issues before you left? Bodywork given? Further emotional support?

Time doula arrived. Time doula departed. Total time doula in attendance.

Debriefing visit:

How did the mother feel after the birth? Any issues? Was any postnatal work done? How did the therapist spend time with the mother after the birth?

Date of first postnatal visit.

Postnatal work

Pregnancy questions

If the therapist is seeing the client for the first time in the postnatal period, then relevant information about the pregnancy and birth history as well as previous pregnancies/births should be obtained. This includes questions about stress, fatigue, and family/friend support.

• What kind of labour?

If the therapist attended the birth this will have been recorded in detail (as above). If the therapist did not attend the birth, then they will need to find out what happened during the birth, both physically and emotionally, in order to inform the postnatal approach.

• How many weeks postnatal?

This is important in order to know what to expect in terms of types of conditions and cautions.

• How are they recovering postnatally?

This includes both emotional and physical aspects of recovery.

• Breastfeeding/feeding issues?

If the mother is breastfeeding, she may need lymphatic work and breast massage or another treatment modality. If she does not wish to have treatment directly from the therapist, she could be shown some self-care modalities.

• Baby.

How is the baby? Any health issues or concerns related to the baby? If the therapist is trained in baby massage, some simple techniques can be shown. Regardless, if the baby is with the mother, it is usually helpful to try to include the baby in the session, perhaps by letting the baby lie beside the mother, encouraging the mother to tend to her baby’s needs, cuddling, feeding or changing her baby. Postpartum care on the floor can be effective in allowing more space for mother/baby bonding.

• Any specific pain in the perineal or groin area?

This is important to screen for possible PGI/SPD. As this could be caused by the birthing process itself, it is worth repeating as a postpartum question.

• Incisions: healing of caesarean section and episiotomy scars.

This is vital to know in order to establish appropriate postnatal work.

• Temperature/fever/discharge of lochia issues.

Cautions/contraindications/modifications

One of the aims of questioning is to establish if there are any situations where the client would need to be referred or if there are any cases where bodywork needs to be modified (Box 8.2, Box 8.3 and Box 8.4).

Box 8.2

Urgent referral in pregnancy

Urgent referral: no bodywork should be carried out until medical diagnosis is made. Women need to be referred immediately to their primary care provider.

• Current uterine bleeding (many causes – see box 8.1 p. 183).

• Loss of amniotic fluid prior to 37 weeks and/or strong contractions; pre-term labour.

• Inability to urinate; UTI with possible bladder complication.

• Severe facial oedema; possible PET.

• Oedema which is visibly increasing and which does not respond to elevation or mobilisations; possible PET, hypertension or kidney issues.

• Severe headache, blurry vision, flashing lights; possible PET.

• Symptoms of shock in woman: pale face, mental confusion, dizziness; possible placental separation or DIC.

• Lack of fetal movement which the woman feels is of concern; possible still-birth or fetal issues.

• Severe vomiting; T1 possible hyperemesis, hydatidiform mole. T2 and 3 premature labour.

• Signs of severe depression or psychosis.

• Suspected thrombosis.

Box 8.3

Signs of eclampsia/toxaemia (PET)

Eclampsia may be a medical emergency. It occurs in the second or third trimesters as it is dependent on there being a placenta.

It may be fine to work with a pre-eclampsic woman with modifications (see high-risk chapter) but if it starts to develop into eclampsia then it is becoming a medical emergency and needs immediate medical referral. The therapist needs to be clear that all the following are possible signs:

• Severe frontal headaches.

• Visual disturbances, e.g. blurry vision, flashing lights.

• Swelling of face; severe including swelling of eyelids.

• Epigastric pain/pain in upper right upper quadrant of abdomen (HELPP syndrome).

• Generalised oedema, more than just some oedema in the legs and arms. It would be experienced throughout the leg and not just in the extremities.

• Severe abdominal pain.

• General malaise, agitation, nausea.

Box 8.4

Urgent referral in the postnatal period

Potential postnatal emergency situations. Immediate referral to primary caregiver without bodywork. After diagnosis bodywork may be an adjunctive therapy to support the healing process.

• Fever. It may indicate uterine infection, bladder or kidney infection, breast infection (mastitis), or other illness.

• Burning with urination, or blood in the urine. This could indicate bladder infection.

• Inability to urinate. Swelling or trauma of urethral sphincter.

• Swollen, red painful area on leg (especially calf) which is hot to touch. Thrombophlebitis – development of blood clot in blood vessel. However, remember that DVTs are not always symptomatic.

• Sore reddened painful area on the breast in addition to fever and flu-like symptoms. Breast infection, mastitis.

• Passage of large red clots, pieces of tissue or return of bright red vaginal bleeding (lochia) after flow has decreased and changed to brownish, pink or yellow

– retained fragment of placenta

– uterine infection

– overexertion.

• Foul odour to vaginal discharge, vaginal soreness or itching. Uterine infection, vaginal infection.

• Increase in pain in episiotomy site, may be accompanied by bleeding or foul-smelling discharge. Infection of episiotomy, reopening of incision or tear, stitches give way.

• Slight opening of caesarean incision, may be accompanied by foul discharge and blood. Infection of caesarean incision.

Testimonial: do not be afraid to refer if you have concerns

I am usually able to work out if a mum has cholestasis from the feet and the abdomen and I have had four cases of this where it has been dismissed by the medical professionals, but I have insisted that the women leave my session and go straight to the hospital for a blood test. It has always proved positive. One women said that her reflexology session saved her life. On arrival at the hospital, the doctor was so shocked at the results of her liver function test that he ordered an immediate caesarean section. Hospital protocols have been changed as a result of this. He said if she had left it for another day then it would have been fatal for her.

(Catherine Tugnait, UK Maternity Reflexologist and Reflexologist Therapist)

Modifications to treatments

In order to understand how treatments should proceed, a clear understanding of the physiological changes occurring in the maternity period is crucial.

If the client is presenting with more pathological conditions, then often work can be done but with modifications. These types of conditions are outlined in the high-risk section. Conditions warranting early referral to primary caregiver but where the therapist may be able to work are outlined in Box 8.5.

Box 8.5

Conditions warranting early referral to primary caregiver but where therapist may decide to work

• Extreme skin itching of hands or feet prior to 37 weeks; possible obstetric cholestasis.

• UTI suspected.

• Suspected diabetes: increased urination, thirst, sweet-smelling breath.

• Soreness in the kidneys with no other symptoms: suspected kidney infection.

• Painful urination with no other symptoms.

• Early signs of potential lymphodynamic oedema with no other symptoms.

Postural assessment

This is key to assessment. It should include some assessment from anterior, lateral and posterior view of the body. It must include an understanding of the physical structures such as joints and muscles as well as how the meridian pathways may be distorted through decompensated posture. The therapist may wish to palpate the bony landmarks of the body. The woman’s posture will show significant movement to change in the areas of most flexibility. Physiotherapy studies (Polden & Mantle 1990) suggest that the increase in kyphosis and lordotic sways in the spine will be exaggerated as the pregnancy progresses.

Usually assessment is made from assessment in the standing posture; considering the anterior, lateral and posterior view. However, in pregnancy alignment may also be assessed while the client is sitting or while she is on all fours.

While the client is sitting (for example on the ball) it can be helpful to notice how the legs support the sitting posture and any alterations in position. The hips will be externally rotated increasingly as the fetus grows in size. While the client is on all fours (for example resting over the ball) assessment can be made of lumbar lordosis and supportiveness of the abdominal muscles. Observation can be made of the shoulders and neck and which way the client places the head.

Assessment can be made of the comfort of the knees in this position and any knee issues may become apparent.

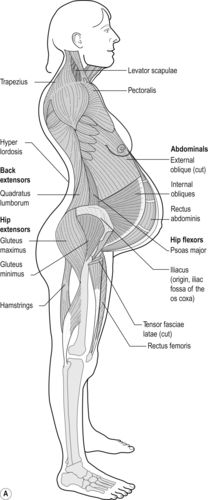

Typical posture of pregnancy

Postural habits pre-pregnancy tend to be exaggerated. The typical posture in later pregnancy is caused by:

• Hyperlordosis. The increasing weight of the abdomen, accompanied by lengthening of the muscle and some weakening of muscle tone, increases anterior pelvic tilt, especially when accompanied by a lack of postural awareness. The increasing weight causes additional work load on the lower vertebrae, lower erectae spinae and transversospinalis groups. The muscles respond to this lengthening by contracting and tightening. This means that lordosis of the lower back is increased.

• Other muscles which tend to be involved in this pattern are:

– Weak or inhibited (hypotonic) – rectus abdominis, transverse abdominus, external and internal obliques, pelvic floor.

– Short and tight (hypertonic) – gluteus maximus and minimus, hip flexors (psoas major and iliacus), rectus femoris, tensor fascia lata (TFL), quadratus lumborum, lumbar erector spinae, iliotibial band as they engage to stabilise the lower back.

• The knee joints tend to be slightly hyperextended. The ankle joints tend to be slightly plantarflexed. There can also be a narrowing of the intervertebral discs and foramen, leading to possible nerve root irritation.

• Sometimes the woman responds to this by bringing the weight back onto the heels to compensate for the forward pull of her body.

• Weight of the baby. Factors here include the weight of the baby and also softening of pelvic joints, external rotation of the hips and compression of the lumbosacral area. The weight of the fetus in the pelvis, combined with the hormonally induced softening of the pelvis, causes a widening of the hips and external rotation.

• This relative pelvic instability may also lead to sacroiliac (SI) joint instability or sacral misalignment. The weight of the fetus may also put pressure on the sacroiliac and sciatic nerves, causing sciatica.

• If the baby is lying in the posterior position, its pressure is likely to be more uncomfortable.

The pelvic floor muscles contract and the uterine tilt is increased anteriorly which perpetuates the postural fatigue of the skeletal muscles with prolonged upright postures and increases the likelihood of uterine muscle contraction.

(Averille Morgan, personal communication, 2008)

Effects on the rest of the body

The neck and shoulders may express patterns of compensation in response to the changes in the pelvis. Typical patterns here can be grinding of the jaw and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) issues and excessive tension in the neck and shoulders:

This is due to the cranial membranes being strained via the sacral attachment. If, for instance, the sacral drag is a result of pelvic muscular or ligament weakness then the spinal membranes are also straining from their interspinal attachments and cranial base attachments. The resultant inferior drag can manifest as throat, sinus and jaw contraction.

(Averille Morgan, personal communication, 2008)

The pelvic position and weight will affect the legs, positions and joints. The gastroncnemius and soleus tend to be hypertonic in addition to the tensor fascia latae and rectus femoris. The adductors tend to be hypotonic. Often there can be a collapsing of the inner arches of the feet (pes planus).

The changing weight necessitates adaptations to changes in the centre of gravity via stretch or contraction of skeletal muscles and disproportionate loading on viscera or fascial structures, eg uterus and mesenteries. Balance may become an issue for pregnant women.

Hyperkyphosis

The increasing weight of the breasts contributes to the postural imbalance in the maternity period. They tend to pull down on the front of the upper body meaning that hyperkyphosis may be an issue. The lungs and front of the body – rib cage and intercostals, diaphragm – tend to become compressed with the result that breathing may become more laboured and there may be thoracic outlet syndrome issues:

With increased anterior fascial strains of the thorax, the thoracic inlet tension increases. This area is important for lymphatic drainage via the lymphatic ducts. Improved respiration using the abdominal diaphragm will encourage the thoracic inlet to reciprocally pump and aid spinal circulation and drainage, gradually improving postural compensation mechanisms.

(Averille Morgan, personal communication, 2008)

Typical patterns

• Short and tight (hypertonic). Sternocleidomastoids, upper trapezius, suboccipitals, levator scapulae, scalenes, pectoralis major and minor, subclavius, serratus anterior, anterior intercostals, splenii, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor.

• Weak or inhibited (hypotonic). Rhomboids, middle trapezius, thoracic erector spinae, suprahyoids, infrahyoids, longus capitis, longus cervicis.

Energy patterns

• Collapsed Lung energy; Kyo patterns more common.

• Wood energy, especially Gall Bladder around the shoulder blade is tight/Kyo sometimes even though the muscles may be weak.

• There can be a narrowing of the intervertebral discs and foramen, leading to possible nerve root irritation.

Individual variations

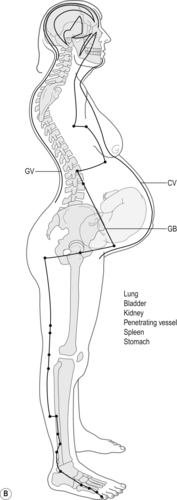

The ‘typical’ presentation of pregnancy will vary (Fig. 8.1). Individual assessment will be needed to determine which of the muscle patterns is present for each client. This is particularly necessary relative to pre-existing musculoskeletal issues. For example if the pelvis is already in lordosis this pattern will be exaggerated. If the pelvis is rotated or higher on one side this will add variation to the basic pattern.

|

|

| Fig. 8.1A and B Typical posture of late pregnancy, showing muscle groups and energy patterns. |

If the client has pre-existing imbalances in their legs, this will affect the pelvic alignment. Shortened or lengthened quads/hamstrings affect the pull on the pelvis and the ASIS and sacrum may be out of alignment.

The focus of postural alignment in pregnancy is primarily to correct excessive anterior pelvic tilting. This includes exercises and techniques which lengthen the lower back, helping to aid posterior tilting of the pelvis to a more neutral position and shortening the abdominal muscles as well as opening the chest and lungs.

Passive movements and joint mobilisations are especially helpful as the fetus tends to create compression in areas of the mother’s body, especially in the pelvis and ribs. Where the fetus is pushing on the maternal pelvis, ligaments and muscles will stretch and at times, strain. Care needs to be taken to monitor the stability of the pubic bone, as PGI becomes a possibility and would result in avoiding movements which could aggravate the symphysis pubis.

Energy patterns: postural

• The postural changes will in turn have an effect on the meridians of the body which will affect the various energies. The main energy that is weakened is the energy of the Kidneys, due to their role in storing the Jing which is sent to the baby and their relationship to the Extraordinary Vessels. This is the energetic root of the lordosis pattern. It would be aggravated by weakness in the lower Bladder area.

• Changes in the pressure on the discs reflect patterns of the Governing Vessel. Blocked energy in the back also reflects blockages in energy of the three burners. The lower burner is considered to be ‘blocked’ by the fetus which in turn affects the middle burner and upper burner energy.

• These postural changes would affect the Yin meridian of the front of the body. There is a tendency for weaker energy in the Yin meridians, especially CV and KD, PV.

• The Yin meridians of the legs are often weaker – SP, LV, KD. The Yang meridians of the legs often compensate by contracting.

• Due to the weakness of the Kidney there is often excess energy blocked in the neck and shoulders, particularly in the Wood meridians of Gall Bladder and Liver.

• All of these patterns need to be assessed individually.

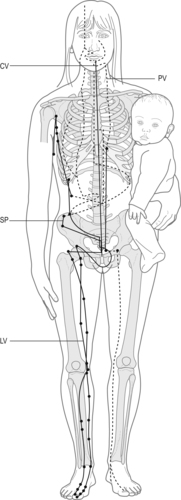

Typical posture postnatally (Fig. 8.2)

|

| Fig. 8.2 Areas weakened through pregnancy and strains placed on the body through caring for young children, showing muscle groups and energy patterns. |

Weakness in the pelvis

The muscles which have been weakened due to the demands of pregnancy (abdominals and pelvic floor), if not appropriately strengthened, may remain potential areas of weakness for the rest of the woman’s life. In the initial postnatal period, the pelvis tends to be even less stable than during pregnancy, due to the pressures of the fetus descending and the forces of opening out in labour and the resulting weakness in the musculature and ligaments. It takes time for the muscles and ligaments to strengthen. Some women continue to have lower back and pelvic issues into the postpartum and beyond. These type of issues will tend to be aggravated by the additional weakness in the abdominal wall caused by a caesarean.

Women may have PGI issues, especially PGI, caused by strain placed on the pubic bone during labour through either prolonged straining in second stage in a squatting position or lying in lithotomy for extended periods straining.

Postnatally women often have tight psoas muscles as these work to support the pelvis.

One-sided patterns due to carrying infant on one hip

Weakness in the pelvis can be further exacerbated by poor posture postnatally. Many mothers carry their infant on one hip, especially as the baby gains weight in the weeks and months post delivery. This creates imbalance in the pelvis and associated muscles with increased strain on that side, especially in the quadratus lumborum, hip flexors, gluteals, and external hip rotators.

Additionally many mothers lift their infant awkwardly, using the lower back rather than the legs for proper leverage. This places additional strain on this area.

Generalised upper body tension

This is due to feeding, lifting and compensating for weakness in the pelvis. This can be accompanied by tension/excessive energy in the head, neck and shoulders, which may be from tension accumulated in delivery and also from poor postural habits when feeding and carrying the baby. The thoracic spine is likely to be kyphotic.

Energy patterns: postnatally

• The area of weakness continues to be the lower back and pelvis which is the Kidney and lower burner. The Hara itself, after the initial changes, expresses with an overall weakness of energy.

• Spleen energy tends to be weak.

• Gall Bladder and Liver energy tends to be blocked; with the upper body tensions.

8.2. Orthopaedic assessment and the maternity client

Caroline Martin

Bodyworkers are trained in the importance of postural assessment as well as in performing orthopaedic tests which provide more specific assessment information. Some tests need to be modified for the pregnant client in order to ensure comfort and safety for her, as well as to gain accurate information about her body during the pregnancy.

A well-performed orthopaedic assessment should include active, passive, resisted and special tests that are specific to the suspected disorder. When performing resisted tests the therapist must create a safe amount of resistance and ask the client to slowly meet his/her resistance. In tests where the abdomen prevents full range it is acceptable to apply gentle pressure against the pregnant abdomen, to the client’s comfort level.

Together all the tests will help better determine what muscles, tendons, joints or nerves are involved and/or affected. These tests are very important in making a differential diagnosis because minor disorders can mimic very serious problems. A proper orthopaedic assessment can mean the difference between a minor inconvenience and a fatal medical condition.

The bodyworker’s role is not to diagnose medical conditions, but to play an important part in referring the client back to her primary healthcare provider for further assessment when it is thought necessary. Whether or not the questions lead to any conclusive assessment, it is still necessary for the therapist to refer the client to the MD with all negative and positive findings documented.

Below is a list of some physical disorders that have similar symptoms but very different diagnoses and which the therapist may encounter with the maternity client:

1. Low back pain caused by tight/strained low back muscles is similar to that caused by kidney problems. This is important because kidney issues may be a factor in pregnant clients. Findings from a back assessment may show that the client has tenderness with certain active ranges of motion (AROM) but if the resisted tests are negative then this suggests there is no muscle involvement. If the passive tests are also negative then this suggests it is not ligament or joint related either. At this point it is important to run through the low back special tests including myotomes and dermatomes, and if these are all negative then the therapist should consider involvement of the kidneys. The therapist can ask questions regarding colour of urine, frequency of urination as well as any signs of burning and unusual odour. The therapist should then refer the client to the appropriate healthcare professional who in turn should do the necessary urine tests to determine if there is any urinary tract or kidney involvement.

2. Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) that presents with left-sided weakness may actually be the signs and symptoms of a mild stroke. It is therefore imperative that the therapist can properly test for TOS.

3. Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) needs to be assessed to determine if it is being caused by tightness of the fascia/muscles/tendons due to excessive swelling in the wrists or whether active trigger points in the neck/shoulder muscles are the cause. The therapist must also consider blood pressure (BP) in addition to swelling. They must determine if the onset of swelling is sudden, dramatic, in the face as well as the arms and legs, and be aware of the additional symptoms as listed in the BP section 1.4 and p. 20. The client may be suffering from pre-eclampsia which needs immediate medical attention.

4. Shoulder pain is often caused by tight neck, shoulder, chest, upper back muscles or may sometimes be due to a rotator cuff bursitis/tendonitis/strain. But shoulder pain that has a sudden onset and is isolated to the left side, and that may or may not show other symptoms of a heart attack, must be properly assessed – referral to a physician may be wiser than a shiatsu/massage treatment.

5. Pain in a client’s leg may be caused by tight, fatigued or cramping calf muscles which are very common during pregnancy. However, these symptoms may actually be due to a deep vein thrombosis (DVT), so it is important to know the difference.

6. Low back pain that exhibits symptoms of a tight iliopsoas muscle is identical to pain caused by an aortic aneurysm. This is an extremely rare complication, especially in pregnancy, so the therapist is unlikely to encounter it. However, any attempt to release an iliopsoas could rupture an aneurysm, and the misdiagnosed client would likely die on the massage table. Although an MRI would be needed to diagnose an aortic aneurysm, an orthopaedic assessment can determine the involvement of the iliopsoas.

Having the training and ability to assess a client orthopaedically ensures an accurate clinical impression and improves quality of care for the client. The knowledge of the individual bodyworker in regards to orthopaedic tests may vary from country to country and there are specific books that discuss orthopaedic testing in great length. We have included tests which cover the main areas of the body most likely to be affected by maternity changes.

Orthopaedic testing and positioning

Generally, near the end of the first trimester, the expectant client will find the prone position too uncomfortable during orthopaedic testing. The therapist will need to adjust and modify their assessment techniques specifically when the pelvic/hip joints are involved. From the middle of the second trimester she is likely to find supine less comfortable. In the postnatal period, prone and supine become testing options once more, although care needs to be taken with clients after surgery, that there is no pain experienced in different positions due to incision discomfort.

Table 8.1 lists the typical joints assessed actively, passively and with restriction. It notes their movements and approximate normal ranges of motion (ROM). For the most part these tests can be done in a seated, semi-reclined or standing position. Often a seated position will be the least compromising, most comfortable, and safest for the maternity client. If supine is the only option, avoid keeping the client in this position for any longer than she is comfortable and be alert to any signs or symptoms of supine hypotension. The values in italic font are the orthopaedic tests that are usually performed prone or supine and positional modifications will be discussed later in this chapter.

| Cervical spine | Thoracic spine | Lumbar spine |

|---|---|---|

| Flexion – 45° | Flexion – 30–40° | Flexion – 80° |

| Extension – 45° | Extension – 20–30° | Extension – 20–30° |

| L/R sideflexion – 45° | L/R sideflexion –20–25° | L/R sideflexion – 35° |

| L/R spinal rotation – 60° | L/R spinal rotation – 35° | L/R spinal rotation – 45° |

| Hip | Knee | Ankle |

| Flexion – 120° | Flexion – 135° | Plantarflexion – 30–50° |

| Extension – 30° | Extension – 0–10° | Dorsiflexion – 20° |

| External rotation – 60° | External rotation – 40° | Eversion – 10° |

| Internal rotation – 40° | Internal rotation – 30° | Inversion – 20° |

| Abduction – 45° | ||

| Adduction – 30° | ||

| Shoulder | Elbow | Wrist |

| Flexion – 180° | Flexion – 140–150° | Flexion – 80–90° |

| Extension – 45–60° | Extension – 0–5° | Extension – 70–90° |

| Abduction – 180° | Pronation – 80–90° | Ulnar deviation – 40° |

| Adduction – 45° | ||

| External rotation – 90° | Supination – 90° | Radial deviation – 30° |

| Internal rotation – 90° | ||

| Horizontal abduction – 45° | ||

| Horizontal adduction – 135° | ||

| External rotation with 90 degrees elbow flexion | ||

| Internal rotation with 90 degrees elbow flexion |

Modifying basic orthopaedic tests for the maternity client

Before discussing maternity positional modifications during an orthopaedic pelvic assessment, it is important to ensure the therapist remembers the minor modifications for other joint assessments.

When testing the cervical spine have the client seated to avoid loss of balance. The therapist will need to support the client at the hips when performing the active range of motion for the thoracic spine while having the client in a standing position. Resisted ranges of motion of the thoracic spine can be done with the client seated.

Active, passive and resisted tests of the shoulder, elbow and wrist can also be achieved with the client in a seated position whereas the knee and ankle assessments can be completed successfully with the client either semi-reclining or seated.

Always test the uninjured side first to determine the client’s normal ranges and rule out the joints above and below the chief complaint site to ensure there are no other complications. Give a full explanation and, where necessary, a demonstration of the testing movements prior to performing the test.

Pelvic assessments of the maternity client

When assessing pelvic disorders a gait analysis and postural assessment should be done first. The therapist should note any strained walking gait such as a ‘waddle’ or limp and use a plumb line for a proper postural assessment to determine the degree of increased kyphosis or lumbar lordosis.

Following the gait and posture analysis a full hip and lumbar assessment must be completed as both regions affect pelvic movement. For example, when the lumbar region is flexed forward a problem with the articulation of the ilia on the sacrum could be detected, just as hip tests can uncover lesions at the sacroiliac joint. The therapist must be aware of any imbalanced movement which could expose hyper- or hypomobility.

Forward lumbar flexion can be performed safely and effectively, even in the later stages of the third trimester, by having the woman seated with her feet firmly on the floor and her legs spread apart enough to accompany her growing belly (Fig. 8.3). As noted in Table 8.1, the hip is tested in six different ranges of motion and the lumbar in four, two bilaterally. Special tests are performed after a full hip and lumbar assessment is completed, followed by palpation. The special tests for the pelvis are discussed later in this chapter.

In assessing the pelvis the therapist must initially test the client in her active range to see if any limitations exist. It is important not to physically stress the client and therefore the therapist needs to avoid having the client switch back and forth from standing, to seated, to semi-reclined and so on. All the active and resisted ranges of motion of the lumbar assessment can be done in the seated position; therefore it is more efficient to test this region first (Fig. 8.4). Due to the increased laxity of ligaments and weight of the perinatal client passive testing can sometimes be awkward and the results inconclusive. Therefore it is best to place a gentle overpressure at the end of each active range of motion as long as the client exhibits normal and pain-free ranges. A normal overpressure end-feel should be a ‘tissue stretch’ sensation for all ranges of the lumbar spine. During the active testing phases in the seated position always stand within a safe close range of the client to assist her should she lose her balance.

|

| Fig. 8.4 Therapist spotting active lumbar extension. |

For the hip assessment all tests that can be done standing should be performed first as the rest will be done with the client semi-reclined. These are: active extension, abduction, adduction, then passive and resisted extension. Position the client beside the therapy table so she can utilise it for support then direct her to extend her leg backwards, out to the side and then across the body. At this stage it is best to test the passive and resisted actions of the client’s hip while she is still standing (Fig. 8.5 and Fig. 8.6). When applying resistance always have the client just meet your resistance and hold the test for 5–15 seconds (Fig. 8.8A).

|

| Fig. 8.5 Active hip adduction. |

|

| Fig. 8.6 Passive hip internal rotation. |

|

|

| Fig. 8.8A and B Resisted hip flexion. (A) Passive external rotation and (B) resisted internal rotation. |

Next position the client semi-reclining. The most logical order of testing in this position is hip flexion, internal rotation, and external rotation actively, passively then resisted. Finish off with passive and resisted abduction and adduction. For active flexion direct the client to bring her knee toward her chest. Have her relax and repeat the movement passively (Fig. 8.7) then with resistance (Fig. 8.8). Again, the expanding abdomen will determine the amount of range enabled. For external and internal rotation have the client turn her foot inwards and outwards while the hip and knee are at 90° of flexion. Next perform the passive and resisted tests of these ranges and then move onto testing abduction and adduction. When performing abduction stabilise the opposite side at the pelvis and thigh. For adduction assist the client by lifting the opposing leg. Resisted adduction can be done with the client semi-reclining, while resisted abduction is most effective with the client side-lying (Fig. 8.9).

|

| Fig. 8.7 Passive hip flexion. |

|

| Fig. 8.9 Resisted hip abduction. |

Throughout the tests note any decreased ranges of motion, abnormal end-feels and pain or discomfort.

Special testing and modifications for common maternity conditions

There are a number of special tests that can be performed to help determine what anatomical structures are involved in a condition. Listed below are just a few examples of common and effective tests. It is highly recommended that therapists should get further training with instructors who are skilled in teaching orthopaedic special tests and assessments if they have not covered this skill in their professional bodywork training.

Compression syndrome tests

Wright’s test

Objective: Test for thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) due to tightness in the pectoralis minor muscle.

Test: With the client seated palpate her radial pulse and then hyperabduct the client’s arm so her hand is brought over her head. Instruct her to take a breath and note if her pulse dissipates. If there is no change have her rotate or extend her head and neck as this may also create a positive test result.

Results: Positive if pulse dissipates or she experiences tingling and numbness in the upper limb.

Adson’s manoeuvre

Objective: Test for TOS related to compression of the brachial plexus caused by tight anterior scalenes.

Test: Locate the radial pulse, have client rotate her head toward the test shoulder. Next ask her to extend her head back while the therapist passively externally rotates and extends the client’s shoulder. Ask the client to take a deep breath and hold it for approximately 15 seconds.

Positive sign: If the pulse fades or disappears.

Travell’s manoeuvre

Objective: Test for TOS related to compression of the brachial plexus caused by tight middle scalenes.

Test: Locate the radial pulse, have client rotate her head away from the test shoulder. Next ask her to extend her head back while the therapist passively externally rotates and extends the client’s shoulder. Ask the client to take a deep breath and hold it for approximately 15 seconds.

Positive sign: If the pulse fades or disappears.

Phalen’s test

Objective: Tests for carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) caused by pressure on the median nerve.

Test: The therapist fully flexes the client’s wrists bilaterally and places them so the posterior aspects of the client’s hands are touching. Gently compress the wrists together for approximately 60 seconds.

Positive sign: Tingling in the first to third digits and the lateral half of the fourth digit.

Straight leg raising (SLR) test

Objective: Tests for disc-related compression disorders.

Test: Position the client in semi-reclined. With the client’s leg straight the therapist internally rotates, slightly adducts and flexes the leg at the hip; discomfort in the posterior leg indicates the hamstrings are tight.

Positive sign: Pain within 40–90° is indicative of a disc-related condition and/or tension on the lumbosacral nerve roots between L4 and L5. If both legs are lifted passively and pain is felt prior to 30° then this is suggestive of an SI joint dysfunction.

Valsalva’s test

Objective: Tests for compression to a spinal nerve due to a herniated disc/tumour/osteophyte.

Test: With the client seated, ask her to take a deep breath and hold it for approximately 15 seconds. At the same time instruct the client to moderately bear down as if emptying her bowels.

Positive sign: Localised pain at site of compression which may radiate downwards. This indicates a possible disc-related disorder.

Note: Avoid this test if the client is beyond 36 weeks or has had any signs or symptoms of early delivery.

Slump test

Objective: Tests for compression/impingement of the dura and/or spinal nerves.

Test: The client is seated, with feet on the floor and legs slightly open. Ask the client to slump so that the spine flexes forward and the shoulders drop toward the floor. At the same time the therapist holds the client’s chin and head up. If there is no reproduction of symptoms then the therapist flexes the client’s neck forward. If there is still no reproduction of symptoms, passively extend the client’s knee and if this does not recreate any symptoms, dorsiflex the foot. Perform test bilaterally (as in Fig. 8.3).

|

| Fig. 8.3 Forward lumbar flexion. |

Positive sign: Pain along the spine or symptoms of sciatica. The pain is usually felt at the site of the lesion.

Hip/sacroiliac joint

Kemp’s test

Objective: Tests for facet or SI joint dysfunction and/or a nerve root lesion due to a herniated disc.

Test: With the client standing the therapist positions him- or herself behind her. The client must extend the spine while laterally flexing and rotating to the affected side. At the same time the therapist controls the movement by holding the client’s shoulder while directing the client to reach towards the back of the opposite knee. Gentle overpressure is applied in extension while the client side-flexes and rotates to the side of pain. Movement continues until limit of range or until symptoms are produced.

Positive sign: If symptoms are reproduced.

Patrick’s/Faber test

Objective: Tests for SI joint dysfunction or a tight piriformis muscle.

Test: With the client seated, the therapist places the client’s leg so that the foot of the test leg is on top of the opposing knee. This places the hip so it is flexed, abducted and externally rotated. The therapist must stabilise the client by placing one hand on the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) of the non-test leg and gently push the test leg down towards the table (Fig. 8.10).

|

| Fig. 8.10 Patrick’s/Faber test. |

Positive sign: If the leg remains above the non-test leg or if the client feels pain in the hip or SI joint.

Transerverse anterior stress test/sacroiliac joint ‘gap’ test

Objective: Tests the stability of the anterior ligaments of the SI joints.

Test: Facing the client, who is semi-reclined, the therapist places his/her left hand on the inside aspect of the client’s left ASIS and the right hand on the right ASIS. Gently apply cross-armed pressure outwards. Normally the direction of pressure is also downwards but this is difficult to do later in the pregnancy. However, the unidirectional position is still quite successful during pregnancy.

Transverse posterior stress test/sacroiliac joint ‘squish’ test

Objective: Tests for stability of the posterior ligaments of the SI joints.

Test: Facing the client, who is semi-reclined, the therapist places his/her right hand on the outside aspect of the client’s left ASIS and the left hand on the right ASIS. Gently apply pressure downwards and inwards.

Positive test: If the client feels discomfort/pain in the SI joints or gluteal region.

Trendelenberg test

Objective: Tests for weakness of gluteus medius or hip instability on the stance side.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree