7 The Knee

7.1 Arthroscopic Synovectomy/Baker’s Cyst

Indication

Larsen 0–III destruction. There must be no significant knee joint instability.

Specific disclosures for patient consent

Recurrence. Infection.

Position

The Baker’s cyst is usually excised first with the patient secured in the lateral position with two pelvic supports. Tilting the table and internally rotating the knee provides a good starting position for a posterior approach to the knee joint.

The pelvic supports are removed following the extirpation, and the patient is turned supine. Arthroscopic synovectomy can then be performed using the same drapes.

Specifics

Preoperative ultrasound of the popliteal fossa (on the day before surgery) to determine the cyst dimensions (Fig. 7‑1 ).

Surgical technique

Baker’s cyst extirpation

Approach, see Fig. 7‑2 . Surgical technique, see Fig. 7‑3, Fig. 7‑4.

Arthroscopic synovectomy

Approach, see Fig. 7‑5 . Surgical technique, see Fig. 7‑6, Fig. 7‑7, Fig. 7‑8, Fig. 7‑9, Fig. 7‑10, Fig. 7‑11, Fig. 7‑12 . For clinically significant synovitis, arthroscopic synovectomy is combined with radiosynoviorthesis 6 weeks postoperatively.

Postoperative aftercare

As a rule, this procedure is followed by radiosynoviorthesis 6 weeks postoperatively.

7.2 Knee Endoprosthesis

Total knee replacement is one of the most common procedures in rheumatoid patients. The knee joint is affected in 90% of patients.

Indication

Larsen III–V destruction with significant clinical symptoms.

Principles for determining treatment

Treatment is initiated in rheumatoid patients earlier than in osteoarthritis patients. This lessens the likelihood of having to treat multiple joints simultaneously in progressive forms, and thereby avoids the lengthy phases of treatment needed to restore mobility.

Regular and relatively close clinical and radiographic monitoring is important if surgical intervention is deferred for a rapidly progressive inflammatory form. It is not uncommon for these progressive forms to develop significant bone degeneration in the space of 3 to 6 months. This significantly worsens the underlying conditions requiring surgical correction. It is also essential to monitor the supporting ligaments. Progressive laxity of the medial collateral ligament poses a difficult problem surgically, particularly in a knee with valgus deformity.

A highly individualized approach is needed when determining indications for endoprosthesis placement in the lower extremities. Certain basic principles, however, have proved successful:

Reconstruction of a knee and hip on the same extremity in order to achieve a strong functional leg.

Proximal before distal: frequently the hips are replaced first.

For significant flexion contracture of the knee and hip, evidence suggests that it is necessary to address the other ipsilateral joint within a very short period of time so as to avoid the formation of a fixed flexion contracture postoperatively.

In specific situations (such as rapid deterioration of multiple joints), unilateral procedures on multiple joints are possible.

Specific disclosures for patient consent

Prosthetic loosening. Bone fracture/perforation. Approximately 3-fold increase in risk of infection. Skin injury (steroid atrophy).

Instruments

Prosthesis system from the manufacturer of choice. Uncoupled (cruciate retaining [CR], anterior stabilized [AS], posterior stabilized [PS]), partially coupled, coupled.

Position

Supine. Leg holder or sandbag with leg support. A radiograph may be needed.

Surgical technique

Synovitis

See Fig. 7‑13, Fig. 7‑14, Fig. 7‑15.

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)

There are no general guidelines as to whether the PCL should be resected or preserved. This ultimately depends upon the operative findings.

Alignment of the components

Rotational alignment is commonly complicated by considerable bone destruction that is found in a number of rheumatoid patients.

Femoral components: Rotational adjustments are made using multiple reference lines simultaneously. See also Fig. 7‑16.

Valgus deformities of up to 20° are often associated with a 5° external rotation with respect to the dorsal femoral condyles. This external rotation can also be significantly greater in more severe deformities. See Fig. 7‑17, Fig. 7‑18, Fig. 7‑19.

Tibial components: In rheumatoid patients, a functional alignment is used for the tibial component. Following implantation of the trial component, the knee is fully mobilized and the position marked.

In addition, an anatomical alignment is carried out based on anatomical landmarks: using the middle of the tibial prosthesis at the junction of the middle third of the patellar ligament as a guide, externally rotate toward the posterior margin of the tibial plateau.

We therefore often alter our surgical procedure for a severe valgus knee deformity: the tibia is osteotomized first, and is then reconstructed. For difficult femoral anatomical landmarks, rotational alignment of the femur is based on the tibia with the aid of the reference lines: Whiteside’s line, epicondyle axis, line of the dorsal condyles.

Aligning

Knee prostheses are implanted with stronger fixation in rheumatoid patients than in osteoarthritis patients. Our experience has shown that knee prostheses have a tendency to loosen again after 5 to 7 years in patients with inflammatory disease. The opposite is true, however, for men with spondyloarthritis. They tend to develop stiffness in the affected knee joint and, therefore, their ligaments should never be tightened excessively during the procedure.

Rheumatoid valgus knee deformity

Rheumatoid valgus knee deformity is more difficult to address than varus deformity.

Classification of valgus knee deformity

Grade I: mild valgus deformity. Stable medial ligament. Synovectomy of the knee joint. Standard approach.

Grade II: lateral contracture, medially still stable. A release of the lateral contracted elements is essential. Testing is performed in both flexion and extension.

Grade III: severe lateral contracture.

Grade IIIa: medial laxity, can be realigned (usually up to approximately 40° deformity under load). Intraoperatively, the femoral and tibial weight-bearing surfaces are first resected. Next, spacers are placed, and the knee is initially released in extension. A coupled prosthesis is used if the knee cannot be adequately aligned in extension.

Grade IIIb: severe medial laxity.

Grade IV: severe medial and lateral laxity.

A coupled prosthesis is specifically indicated in patients with rapidly progressive and highly inflammatory forms. Approximately 1 to 2% of rheumatoid knee joints fall into this category.

Realigning the contracted lateral structures

Extension contracture: the flexion gap is expanded with a bent Hohmann retractor with the knee placed in flexion. The osteophytes are removed by keeping the osteotome continually aimed toward the bone and as perpendicular to the femur as possible. The posterior capsule is elevated off the femur and pushed proximal with a curved rasp. See Fig. 7‑20 for alternative.

Iliotibial band

The iliotibial band is dissected extra-articularly. This is accomplished by identifying and exposing the iliotibial band extra-articularly at the level of the joint. The most severely contracted fibers are palpated and released with stab incisions. The tract is then manually stretched. This is repeated until adequate alignment is achieved.

Alternatively, the tract can be exposed intra-articularly; however, the operative view is significantly reduced, so much so that we use this approach only for mild contractures. See also Fig. 7‑21.

If an underlying lateral contracture persists, and the situation warrants, the popliteal tendon is then released.

The lateral ligament is addressed next. An initial release is performed by making stab incisions with subsequent re-expansion. If this is not adequate, the ligament itself can be released or the bones can be osteotomized and subsequently refixed. The latter, however, requires that the remaining joint stabilizers be of sufficient caliber.

Rheumatoid varus knee deformity

Rheumatoid varus knee deformity with medial ligament contracture is less common. See Fig. 7‑22.

Anchoring

Bone cement should be used for fixation of prosthesis components because most patients have preexisting osteopenia.

For severe osteoporosis, the shaft of the tibial component is cemented. If necessary, the stability of the entire assembly can be increased with a tibial shaft extension. An overall extension of 80 mm is usually adequate, even in complex cases. See Fig. 7‑23.

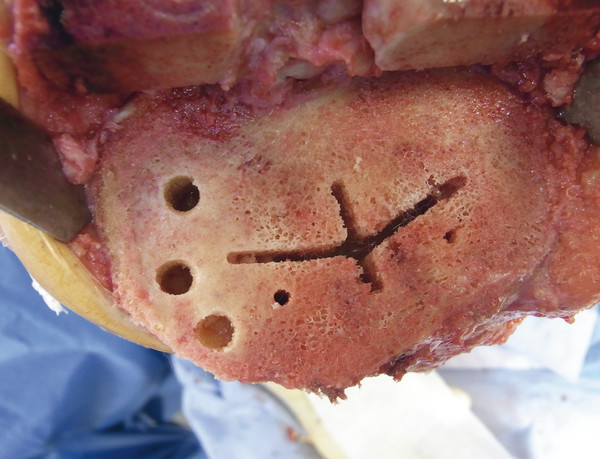

Bony defects

Multiple techniques can be used for reconstruction of tibial defects. Very small, contained defects are filled with cancellous bone or cement. Reconstruction of large defects is often performed with resected bone/transplants taken from the opposite side of the tibia. Augmentations for repair of large defects have also become commonplace. See Fig. 7‑24, Fig. 7‑25, Fig. 7‑26, Fig. 7‑27, Fig. 7‑28, Fig. 7‑29.

Complex instability

See Fig. 7‑30, Fig. 7‑31, Fig. 7‑32, Fig. 7‑33.

Retropatellar facet replacement

According to the literature, rheumatoid patients have slightly better clinical results if they also undergo retropatellar facet replacement. For us, the amount of clinical destruction plays an important role in determining surgical indications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree