PROCEDURE 47 Stabilization of Thoracic, Thoracolumbar, and Lumbar Fractures

Indications

Instability of the posterior ligamentous complex, including fracture-dislocations/subluxations, unstable burst fractures, and flexion-distraction injuries

Instability of the posterior ligamentous complex, including fracture-dislocations/subluxations, unstable burst fractures, and flexion-distraction injuries• Basic principles for fracture management are (1) early decompression ± reduction, (2) stabilization, and (3) early mobilization.

• Surgical approaches are anterior, posterior, or combined approaches depending on the injury morphology, the integrity of the posterior ligamentous complex, and the patient’s neurologic status (intact vs. incomplete vs. complete).

• Methylprednisolone is a treatment option and is not mandatory for blunt spinal cord trauma in many spine centers. There are potential adverse events related to high-dose steroids, including higher incidence of early infections.

Examination/Imaging

Advanced Trauma Life Support protocols should be followed, including complete primary and secondary survey and ASIA assessment and detailed documentation of preoperative neurologic status.

Advanced Trauma Life Support protocols should be followed, including complete primary and secondary survey and ASIA assessment and detailed documentation of preoperative neurologic status. Plain supine radiographs are obtained in anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views, including areas outside of the primary injury site to rule out noncontiguous fractures (can occur in 20% of patients with thoracolumbar and lumbar fractures).

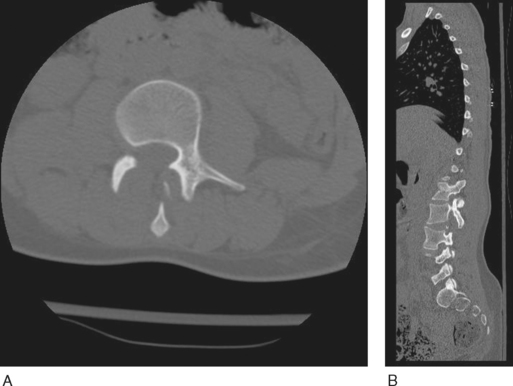

Plain supine radiographs are obtained in anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views, including areas outside of the primary injury site to rule out noncontiguous fractures (can occur in 20% of patients with thoracolumbar and lumbar fractures). Computed tomography (CT) scans with axial images and sagittal/coronal reconstructions are obtained for assessment of bony morphology and canal encroachment by bony fragments.

Computed tomography (CT) scans with axial images and sagittal/coronal reconstructions are obtained for assessment of bony morphology and canal encroachment by bony fragments.• CT visualizes the cervicothoracic region, which is difficult to assess with radiographs. CT scans also assess levels above and below the injury to see if there are additional fractures and to assess pedicle diameters/trajectories for screw insertion.

• In Case 1, preoperative axial (Fig. 1A) and sagittal (Fig. 1B) CT scans show disruption of the posterior ligamentous complex through the facet joint.

• In Case 2, a preoperative CT scan shows a burst fracture of L2 with retropulsion of the posterior vertebral body wall; however, the posterior ligamentous complex is intact (Fig. 2). This patient had symptomatic cauda equina compression.

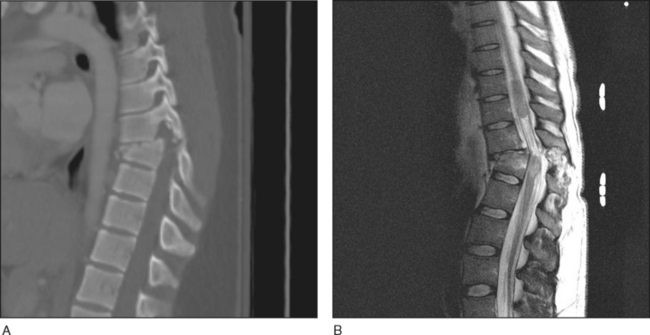

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is done in selected patients to assess the spinal cord for signal change and neural element compression by soft tissue structures such as traumatic disk herniations and epidural hematomas, and evidence of disruption of the posterior ligamentous complex.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is done in selected patients to assess the spinal cord for signal change and neural element compression by soft tissue structures such as traumatic disk herniations and epidural hematomas, and evidence of disruption of the posterior ligamentous complex.• In Figure 4A, a sagittal CT reconstruction shows a thoracic fracture-dislocation with perched facets.

• A sagittal T2-weighted MRI of the same patient (Fig. 4B) shows significant spinal cord edema and contusion at the level of the bony injury extending proximally. Clinically, this patient’s sensory level matched the bony injury level.

Surgical Anatomy

POSTERIOR APPROACH

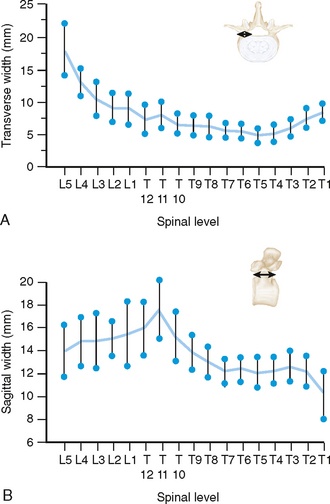

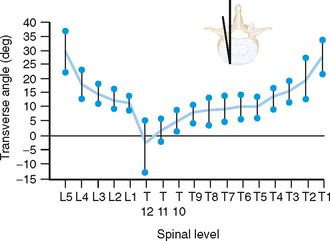

Surgeons performing instrumentation should be familiar and comfortable with pedicle screw insertion landmarks, as well as pedicle screw trajectories and diameters, which vary from T1 down to S1.

Surgeons performing instrumentation should be familiar and comfortable with pedicle screw insertion landmarks, as well as pedicle screw trajectories and diameters, which vary from T1 down to S1.• Figure 5 shows changing pedicle diameters in terms of transverse width (Fig. 5A) and sagittal width (Fig. 5B). In the thoracic spine, the transverse width of the pedicles is smaller than 9 mm, with the narrowest at T5. In the lumbar spine, the narrowest transverse width occurs at L1.

The spinal cord is at risk from medial pedicle screw breaches.

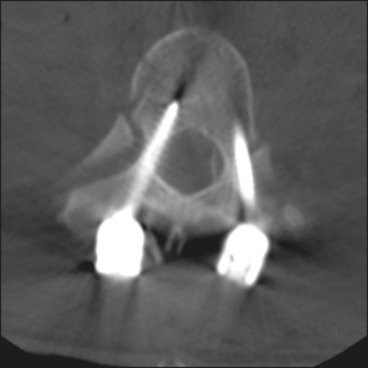

The spinal cord is at risk from medial pedicle screw breaches.• Figure 7 shows a right-sided medial breach by a thoracic pedicle screw as seen on CT scan. Mild breaches such as this one have no impact on the patient’s clinical outcome. Inferior pedicle breaches can lead to nerve root injuries.

• Perforation of the anterior vertebral body may lead to vascular complications, including aortic perforation.

The thoracic spinal canal is narrowed, with decreased space for the cord, and there is a watershed zone for the blood supply. Both factors can lead to spinal cord injury with less canal intrusion than in other regions of the spinal column.

The thoracic spinal canal is narrowed, with decreased space for the cord, and there is a watershed zone for the blood supply. Both factors can lead to spinal cord injury with less canal intrusion than in other regions of the spinal column.• Posterior approach

Pad all bony prominences with gel padding, including the chest, arms, pelvis, knees, feet, and the malleoli between the ankles.

Pad all bony prominences with gel padding, including the chest, arms, pelvis, knees, feet, and the malleoli between the ankles.

A Jackson table also allows a protuberant abdomen to hang freely. This minimizes intra-abdominal pressure, reducing blood loss from venous bleeding during spinal decompression. This also minimizes changes in pulmonary compliance, making ventilation easier in an obese individual in the prone position.

A Jackson table also allows a protuberant abdomen to hang freely. This minimizes intra-abdominal pressure, reducing blood loss from venous bleeding during spinal decompression. This also minimizes changes in pulmonary compliance, making ventilation easier in an obese individual in the prone position.

Pad all bony prominences with gel padding, including the chest, arms, pelvis, knees, feet, and the malleoli between the ankles.

Pad all bony prominences with gel padding, including the chest, arms, pelvis, knees, feet, and the malleoli between the ankles. A Jackson table also allows a protuberant abdomen to hang freely. This minimizes intra-abdominal pressure, reducing blood loss from venous bleeding during spinal decompression. This also minimizes changes in pulmonary compliance, making ventilation easier in an obese individual in the prone position.

A Jackson table also allows a protuberant abdomen to hang freely. This minimizes intra-abdominal pressure, reducing blood loss from venous bleeding during spinal decompression. This also minimizes changes in pulmonary compliance, making ventilation easier in an obese individual in the prone position.• Heavier weighted individuals can develop complications related to prone positioning after prolonged surgery, such as meralgia paresthetica, despite adequate padding.

ANTEROLATERAL APPROACH

Vital structures vary depending on whether the level being approached is thoracic, thoracolumbar, or lumbar.

Vital structures vary depending on whether the level being approached is thoracic, thoracolumbar, or lumbar. In the thoracic or the thoracoabdominal approach, the neurovascular bundle under the rib is at risk during initial rib resection, and during closure from stitches.

In the thoracic or the thoracoabdominal approach, the neurovascular bundle under the rib is at risk during initial rib resection, and during closure from stitches. With a thoracic anterolateral approach, structures at risk include but are not limited to the aorta, lung, heart, nerve roots in the foramen, and segmental vessels, including the artery of Adamkewitz.

With a thoracic anterolateral approach, structures at risk include but are not limited to the aorta, lung, heart, nerve roots in the foramen, and segmental vessels, including the artery of Adamkewitz.Positioning

POSTERIOR APPROACH

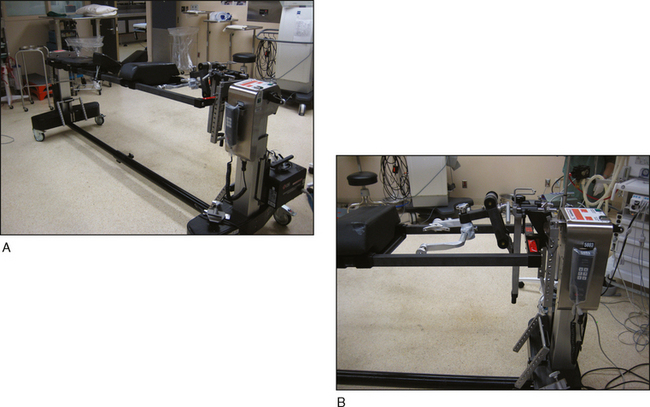

For incomplete spinal cord injuries with an unstable thoracic or thoracolumbar spine fracture, a Jackson table utilizing 360° rotation provides safer rotation into the prone position than manual logrolling with assistants (Fig. 8A).

For incomplete spinal cord injuries with an unstable thoracic or thoracolumbar spine fracture, a Jackson table utilizing 360° rotation provides safer rotation into the prone position than manual logrolling with assistants (Fig. 8A). For high thoracic fractures, Mayfield pins attached to the Jackson table (Fig. 8B), rather than a foam cushion or pad, can minimize external pressure on the eyeballs, which can be a factor in the development of blindness following spine surgery.

For high thoracic fractures, Mayfield pins attached to the Jackson table (Fig. 8B), rather than a foam cushion or pad, can minimize external pressure on the eyeballs, which can be a factor in the development of blindness following spine surgery.ANTEROLATERAL APPROACH

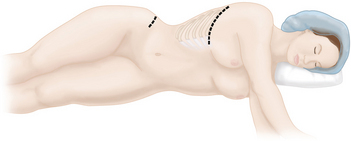

Lateral decubitus positioning with the left side up is used for most lumbar retroperitoneal, thoracoabdominal, and thoracotomy approaches to the spine (Fig. 9).

Lateral decubitus positioning with the left side up is used for most lumbar retroperitoneal, thoracoabdominal, and thoracotomy approaches to the spine (Fig. 9).• Left side up, over a beanbag, on a radiolucent operating table is used for injuries at the level of T5 and below.

The patient is positioned over the break in the table so flexion of the table will permit lateral flexion.

The patient is positioned over the break in the table so flexion of the table will permit lateral flexion.• For lumbar retroperitoneal approaches, the lumbar spine should be placed directly over a break in the table, which is then flexed down to increase the opening between the ribs and the pelvis. However, this break in the table should be straightened out prior to reconstructing the vertebral body; otherwise the cage will be placed in a angled position relative to the end plates.

A roll is placed under the axilla, and the upper arm is placed in a position over a pillow or armboard.

A roll is placed under the axilla, and the upper arm is placed in a position over a pillow or armboard. The beanbag should not come higher than the umbilicus anteriorly and the spinous processes posteriorly.

The beanbag should not come higher than the umbilicus anteriorly and the spinous processes posteriorly.• Posterior approach

A Jackson table provides a radiolucent frame that also allows for 360° rotation, making positioning safer.

A Jackson table provides a radiolucent frame that also allows for 360° rotation, making positioning safer.

A Jackson table provides a radiolucent frame that also allows for 360° rotation, making positioning safer.

A Jackson table provides a radiolucent frame that also allows for 360° rotation, making positioning safer.Portals/Exposures

A decision needs to be made whether the injury will be treated from the back only, front only, or both.

A decision needs to be made whether the injury will be treated from the back only, front only, or both.• Reasons for selecting a particular approach depend on bony fracture morphology, neurologic status, and integrity of the posterior ligamentous complex.

The posterior-only approach can be performed in patients with disruption of the posterior ligamentous complex who are intact neurologically or if neurologically complete.

The posterior-only approach can be performed in patients with disruption of the posterior ligamentous complex who are intact neurologically or if neurologically complete. Reasons for an anterolateral approach are (1) to restore anterior column biomechanical support and (2) a need for decompression.

Reasons for an anterolateral approach are (1) to restore anterior column biomechanical support and (2) a need for decompression.• The anterolateral approach can be done as the primary means of decompression and stabilization without a posterior approach if the posterior ligamentous complex is intact.

• If the spine is not stabilized adequately after use of the anterolateral approach (i.e., the posterior ligamentous complex is disrupted, such as in a severe burst fracture, or the bone quality is poor), a posterior approach may then be needed to supplement fixation and restore stability to the posterior ligaments.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree