PROCEDURE 36 Fractures of the Talus

Introduction

Talus fractures have traditionally been challenging injuries for orthopedic surgeons for a number of reasons.

Talus fractures have traditionally been challenging injuries for orthopedic surgeons for a number of reasons.• Displaced fractures of the talar neck were considered surgical emergencies as time to reduction was thought to play a role in the risk for osteonecrosis.

• Outside of trauma centers, these are relatively infrequent injuries, representing less than 1% of all fractures (Santavirta et al., 1984); their rarity coupled with the technical challenge of reduction and fixation make for surgeon discomfort.

• Given they are associated with high-energy injury mechanisms, these fractures are often accompanied by other injuries in a polytrauma scenario.

Some of these considerations have evolved.

Some of these considerations have evolved.• Evidence has suggested that time to reduction is not a risk factor for eventual osteonecrosis of the talar body following talar neck fractures (Lindvall et al., 2004; Vallier et al., 2004).

• Standard approaches involving two incisions, with malleolar osteotomy if needed, have improved ease and accuracy of reduction, while smaller and more adaptable implants have widened fixation options.

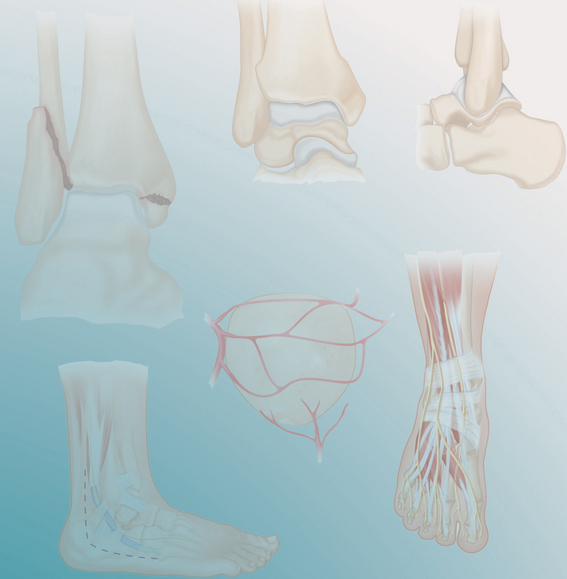

Talus fractures can be divided by the part of the bone affected: body, neck, and lateral process.

Talus fractures can be divided by the part of the bone affected: body, neck, and lateral process.• Talar neck fractures are defined as those occurring anterior to the lateral process, while those of the body occur through or posterior to this process.

• On the plantar side of the talus, the former may involve the tarsal canal or more rarely the middle facet of the subtalar joint, whereas the latter damage the larger and more critical posterior facet of the subtalar joint in addition to the tibiotalar joint on its dorsal surface (Inoguchi et al., 1996).

Extruded talar bodies are dramatic injuries.

Extruded talar bodies are dramatic injuries.• The decision is between reducing the body, with the inherent risk of infection, versus its removal, with the loss of significant bone stock resulting in greater reconstruction challenges.

• A study by Smith et al. (2006) has underlined the safety of retaining and reducing the extruded talus following aggressive irrigation and débridement.

The most widely referenced classification for talar neck fractures is that of Hawkins (1970). Its utility relates to understanding fracture displacement as well as prognosis with regard to osteonecrosis.

The most widely referenced classification for talar neck fractures is that of Hawkins (1970). Its utility relates to understanding fracture displacement as well as prognosis with regard to osteonecrosis.• Although time to reduction and fixation has not been correlated to the eventual incidence of osteonecrosis following a fracture of the talar neck, there remain indications for the emergent reduction of a displaced fracture, including skin compromise and impending necrosis, vascular and/or neurologic compromise from compression or tension, and open injuries.

Closed or percutaneous manipulation of closed fractures can be employed for the initial reduction, followed by formal open reduction and internal fixation when soft tissue and manpower conditions are optimal.

Closed or percutaneous manipulation of closed fractures can be employed for the initial reduction, followed by formal open reduction and internal fixation when soft tissue and manpower conditions are optimal.

In the case of irreducible dislocation, open reduction and fixation should be carried out immediately.

In the case of irreducible dislocation, open reduction and fixation should be carried out immediately.

In the case of talar body dislocation, reduction can be rendered difficult by buttonholing of the body between the posteromedial tendons. Patience coupled with judicious traction, rotation, and angulation will typically result in reduction. Pins and Kirschner wires in the talus can be used as joysticks, while a calcaneal pin can aid in distraction.

In the case of talar body dislocation, reduction can be rendered difficult by buttonholing of the body between the posteromedial tendons. Patience coupled with judicious traction, rotation, and angulation will typically result in reduction. Pins and Kirschner wires in the talus can be used as joysticks, while a calcaneal pin can aid in distraction.

Closed or percutaneous manipulation of closed fractures can be employed for the initial reduction, followed by formal open reduction and internal fixation when soft tissue and manpower conditions are optimal.

Closed or percutaneous manipulation of closed fractures can be employed for the initial reduction, followed by formal open reduction and internal fixation when soft tissue and manpower conditions are optimal. In the case of irreducible dislocation, open reduction and fixation should be carried out immediately.

In the case of irreducible dislocation, open reduction and fixation should be carried out immediately. In the case of talar body dislocation, reduction can be rendered difficult by buttonholing of the body between the posteromedial tendons. Patience coupled with judicious traction, rotation, and angulation will typically result in reduction. Pins and Kirschner wires in the talus can be used as joysticks, while a calcaneal pin can aid in distraction.

In the case of talar body dislocation, reduction can be rendered difficult by buttonholing of the body between the posteromedial tendons. Patience coupled with judicious traction, rotation, and angulation will typically result in reduction. Pins and Kirschner wires in the talus can be used as joysticks, while a calcaneal pin can aid in distraction.Indications

Talar neck fractures

Talar neck fractures• True Hawkins type I fractures (i.e., those that are completely undisplaced) are rare and can be treated nonoperatively with cast immobilization until fracture union (6–8 weeks).

• Displaced talar neck fractures (Hawkins types II–IV) require surgery if the patient’s overall condition permits it.

Examination/Imaging

Physical examination reveals circumferential swelling of the hindfoot in all types of talus fractures.

Physical examination reveals circumferential swelling of the hindfoot in all types of talus fractures.• Talar neck fractures

♦ Gross deformity is noted in cases of dislocation of the subtalar joint, typically posteromedially.

♦ Tension on the flexor tendons will cause toe flexion deformity, and plantar sensation may be decreased if the tibial nerve is affected.

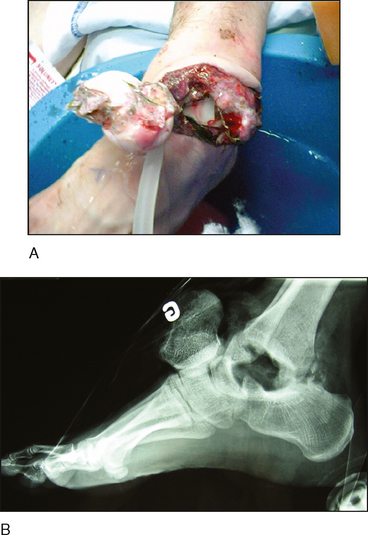

♦ Open injuries typically occur on the medial hindfoot and may include extrusion of the talar body (Fig. 1A).

Radiographic imaging of talus fractures includes anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and oblique views of the ankle and foot. Figure 1B shows a lateral radiograph of the talus extrusion seen in Figure 1A.

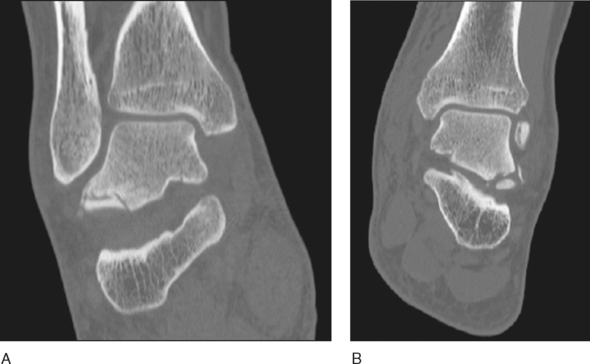

Radiographic imaging of talus fractures includes anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and oblique views of the ankle and foot. Figure 1B shows a lateral radiograph of the talus extrusion seen in Figure 1A. The precise degree and direction of displacement, as well as associated injuries, in all three fracture types can be ascertained with computed tomography (CT) scanning of the hindfoot, including multiplanar reconstructions.

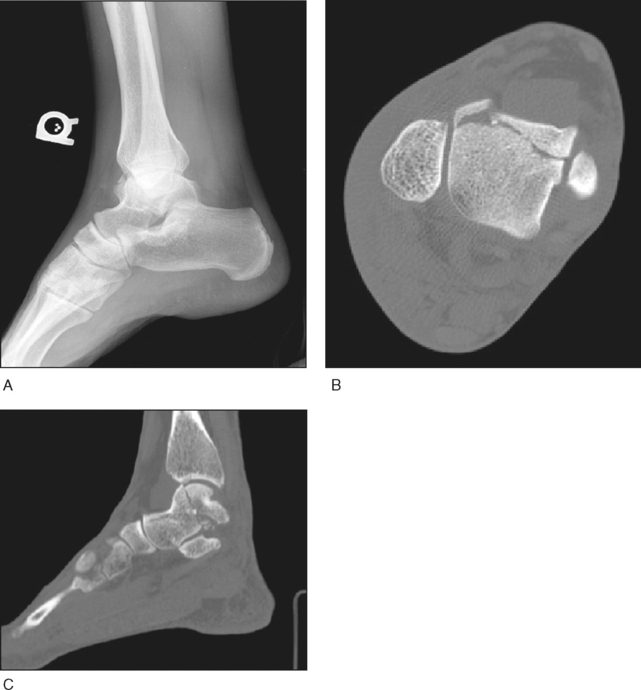

The precise degree and direction of displacement, as well as associated injuries, in all three fracture types can be ascertained with computed tomography (CT) scanning of the hindfoot, including multiplanar reconstructions.• Talar body fracture

♦ In Case 2, the talar body fracture with comminution of the anterolateral talar dome seen on a lateral radiograph (Fig. 3A) was confirmed on an axial CT scan (Fig. 3B). Note that the fracture line involves both the ankle and subtalar joint surfaces on a sagittal-plane CT scan reconstruction (Fig. 3C).