PROCEDURE 31 Tibial Shaft Fractures

Indications

• For patients with narrow canals and thick cortices (e.g., young athletes), one must ensure the availability of appropriate nail diameters (especially in centers with smaller inventories), and be open to other non-nailing options.

• Malunited or un-united fractures may have an occluded or misaligned canal that can be difficult to manage with intramedullary (IM) techniques.

• Established infection (including external-fixator pin track infections) is a contraindication to immediate IM nailing.

• Some surgeons are reluctant to use IM nailing for Gustilo-Anderson type IIIB and type IIIC open fractures, although the available evidence suggests that acute nailing of such fractures is not associated with higher infection rates.

Examination/Imaging

Key elements in the history that are worth emphasizing are the patient’s social and psychological history, which can have an important impact on healing.

Key elements in the history that are worth emphasizing are the patient’s social and psychological history, which can have an important impact on healing. Physical examination

Physical examination• A standard Advanced Trauma Life Support approach is used to look elsewhere for associated musculoskeletal and other injuries (including the ipsilateral femur, proximal tibia, and distal tibia).

• The soft tissues are examined carefully and the extent of soft tissue damage, including the location, size and contamination of any open wounds, is documented.

• The limb’s vascular status and the sensory and motor function of all its nerves are carefully documented.

• The patient’s pain level and analgesic demand are documented, and the status of the leg’s four compartments (including the passive stretch test) is thoroughly evaluated, reassessing it periodically for the development of compartment syndrome.

Imaging studies

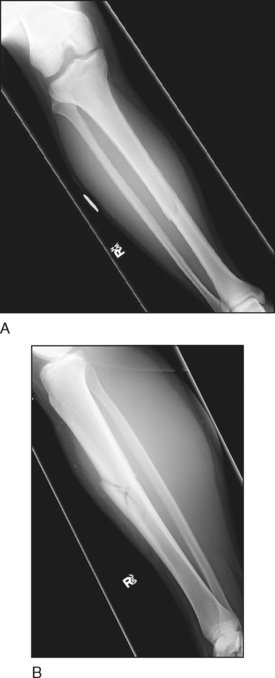

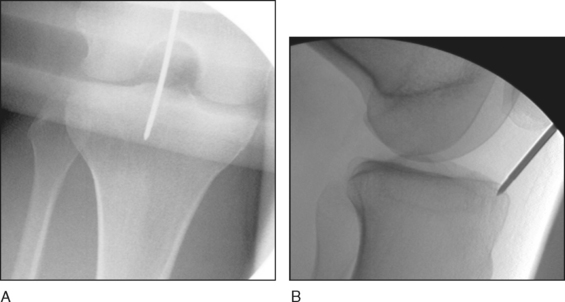

Imaging studies• Anteroposterior (AP) (Fig. 1A) and lateral (Fig. 1B) views of the tibia and fibula, showing the knee and ankle joints, are obtained. The radiographic views must be orthogonal and include the whole tibia and fibula.

• If the fracture extends to the proximal or distal third of the tibia, or if there are symptoms or signs to suggest injury to the knee or ankle, views focused on the appropriate joint should be included.

Surgical Anatomy

Osseous anatomy

Osseous anatomy• The proximal tibia has an apex-anterior angulation of about 15°. Its medullary canal becomes tubular 5–10 cm from the tibial tubercle and has thick walls, especially anteriorly, where the crest occupies approximately one third of the bone’s diameter. Those walls become narrower distally (a feature that makes that segment prone to spiral fractures under torsional forces).

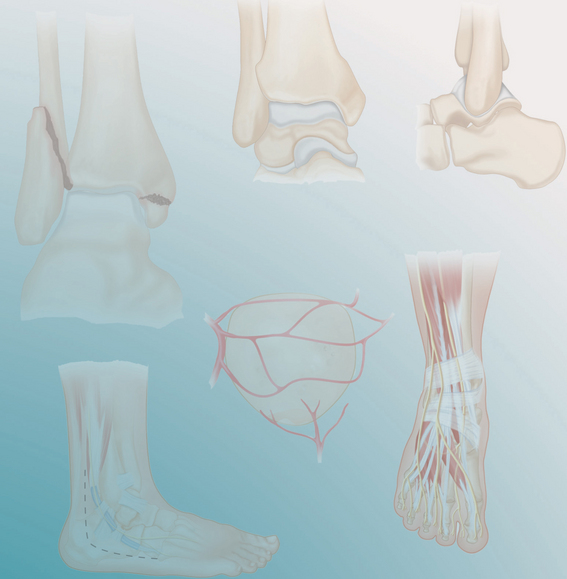

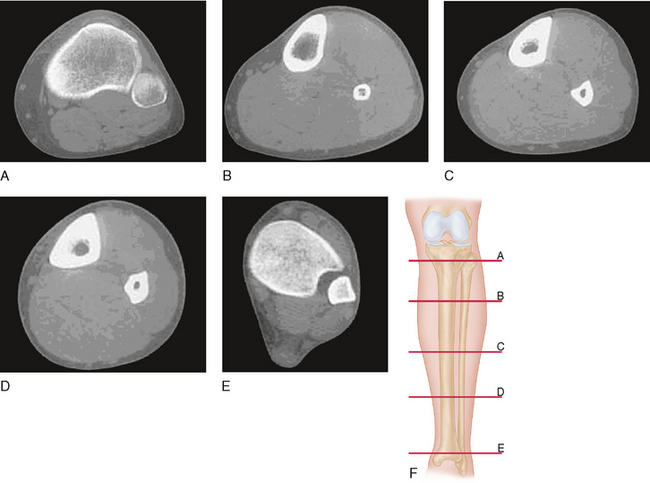

• The diaphyseal canal is significantly rounder in cross section than the tibia’s external appearance would suggest (Fig. 2A–F). Still, even after reaming, a snug fit for an intramedullary (IM) nail can be obtained only in the middle few centimeters (the isthmus) of the tibia.

• The anteromedial surface of the distal tibia is noted to have a fairly consistent concave contour—enough to suggest a varus deformity if one looks at the subcutaneous outline rather than the bone’s central axis. Restoring this concavity is an essential part of reducing distal tibial shaft fractures.

Vascular anatomy

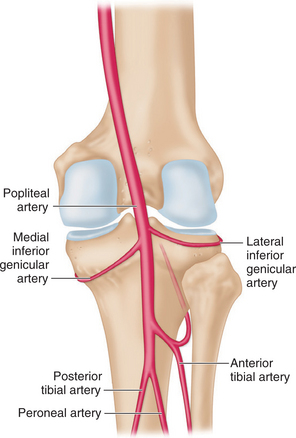

Vascular anatomy• The trifurcation of the popliteal artery begins with the branching and anterior migration of the anterior tibial artery about 5 cm distal to the tibial plateau and just proximal to the interosseous membrane. About 3.5 cm further distally, the posterior tibial artery gives off the peroneal artery, which remains in the posterior compartment (Fig. 3)

• In greater than 90% of patients, the tibia has a single proximal nutrient artery coming from the posterior tibial artery. This artery is easily injured in its long foramen by displacement of a diaphyseal fracture.

• The tibial diaphysis has few extraosseous vessels compared to the metaphyses. After a fracture, the extraosseous vessels—normally vascularising only one quarter to one third of cortical thickness—take over much of the cortical arterial supply adjacent to the fracture site. They also nourish the metabolically active peripheral callus.

• If the diaphysis distal to the injury loses its extraosseous blood supply through severe soft tissue stripping, it is placed at risk for osteomyelitis and nonunion.

Structures at risk

Structures at risk• At the proximal tibia, the popliteal artery is tethered closely to the bone, placing it (as well as the adjacent tibial nerve) at risk of avulsion or laceration with proximal tibial fractures. Another instance in which the popliteal artery can be at risk is during the insertion of AP locking screws or blocking screws.

• The deep peroneal nerve enters the anterior compartment at the level of the tibial metaphysis and is thus at risk of injury during proximal locking screw insertion.

• Running anteromedial to the distal tibia are the saphenous nerve and vein, which can be damaged during mediolateral distal locking screw insertion. Similarly, the anterior tibial vessels, tibialis anterior tendon, and long extensor tendons can also be injured or irritated by AP distal locking screws.

• Ensure that the femoral bolster is not compressing the popliteal fossa and the lateral stop is placed well away from the fibular head.

Positioning

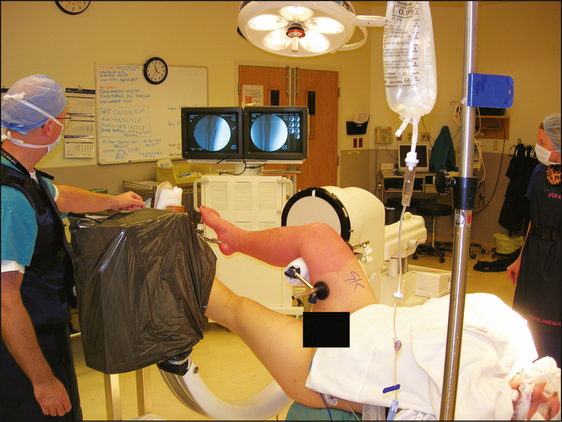

Tibial nailing is done with the patient in a supine position. Image intensification is essential for closed nailing, and so a radiolucent table must be used.

Tibial nailing is done with the patient in a supine position. Image intensification is essential for closed nailing, and so a radiolucent table must be used. A number of reduction and temporary fixation strategies are available for nailing of tibial shaft fractures, and each influences positioning.

A number of reduction and temporary fixation strategies are available for nailing of tibial shaft fractures, and each influences positioning.• Positioning and closed reduction over a triangular frame is a common technique that is done with the patient placed supine on a radiolucent table. Temporary fixation with an external fixator is also done with the patient supine on a radiolucent table.

Using sterile technique, a transcalcaneal traction wire is inserted, using a sturdy Kirschner wire inserted into the medial aspect of the calcaneus approximately 2.5 cm anterior and 2.5 cm proximal to the heel’s posterior and plantar edges, respectively. In Figure 4, the patient’s right leg had undergone débridement and irrigation for an open fracture, and his left was immobilized due to ligamentous instability.

Using sterile technique, a transcalcaneal traction wire is inserted, using a sturdy Kirschner wire inserted into the medial aspect of the calcaneus approximately 2.5 cm anterior and 2.5 cm proximal to the heel’s posterior and plantar edges, respectively. In Figure 4, the patient’s right leg had undergone débridement and irrigation for an open fracture, and his left was immobilized due to ligamentous instability. The involved side’s hip is flexed to just under 90° and the knee to just beyond 90°. This position is maintained with a padded bolster posterior to the distal thigh, but proximal to the popliteal space. Neutral hip abduction/adduction is ensured with medial and lateral stops attached to the bolster. The thigh and leg should be aligned as viewed from the distal end of the table.

The involved side’s hip is flexed to just under 90° and the knee to just beyond 90°. This position is maintained with a padded bolster posterior to the distal thigh, but proximal to the popliteal space. Neutral hip abduction/adduction is ensured with medial and lateral stops attached to the bolster. The thigh and leg should be aligned as viewed from the distal end of the table. With the involved limb in the above position, the calcaneal traction wire is attached to the traction table through the appropriate connector, and its sharp tips are bent inward for safety.

With the involved limb in the above position, the calcaneal traction wire is attached to the traction table through the appropriate connector, and its sharp tips are bent inward for safety. With its foot well padded and secured in its traction boot, the uninvolved limb is placed in knee extension and slight hip flexion, its foot adjacent to the foot of the operative side. This allows easy movement of the image intensifier while not obstructing access to the operative side (Fig. 5).

With its foot well padded and secured in its traction boot, the uninvolved limb is placed in knee extension and slight hip flexion, its foot adjacent to the foot of the operative side. This allows easy movement of the image intensifier while not obstructing access to the operative side (Fig. 5). At this point, the image intensifier is brought in from the lateral side of the involved limb, and adequate biplanar imaging ensured at all levels of the tibia.

At this point, the image intensifier is brought in from the lateral side of the involved limb, and adequate biplanar imaging ensured at all levels of the tibia. Then, closed fracture reduction is performed with the necessary traction applied under fluoroscopy. Adequate reduction of length, alignment, translation, and rotation must be obtained prior to surgical preparation and draping, with minor changes to the reduction made later during the procedure.

Then, closed fracture reduction is performed with the necessary traction applied under fluoroscopy. Adequate reduction of length, alignment, translation, and rotation must be obtained prior to surgical preparation and draping, with minor changes to the reduction made later during the procedure.• Only the skin should be incised sharply when placing locking screws, with all deeper dissection done bluntly with a hemostat. This avoids injury to the structures mentioned in the Surgical Anatomy section.

• During nail entry point selection, if the tibia is in external rotation (as it tends to fall), the selected location will tend to be quite different from the optimal one shown in Figure 6. This is especially important for proximal-third tibial fractures.

Portals/Exposures

Before the proximal incision is made, fluoroscopy can be used with a guidewire laid onto the skin to reference the optimal entry point position and guidewire orientation.

Before the proximal incision is made, fluoroscopy can be used with a guidewire laid onto the skin to reference the optimal entry point position and guidewire orientation.• The optimal nail entry point, in terms of minimizing damage to the articular tissues as well as alignment with the tibial canal, has been demonstrated to be “just medial to the lateral tibial spine” on the AP view (Fig. 6A) and “immediately adjacent and anterior to the articular surface” on the lateral view (Fig. 6B).

• The cadaveric photograph in Figure 7 shows the intra-articular structures at risk with an entry point located too posterior (Hernigou and Cohen, 2000).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree