CHAPTER 3. Western approach to the postpartum

See labour Chapter 2, Chapter 6 and Chapter 13 and practical section Chapter 10

For more information on:

Effects of birth

• Define the postpartum period for the mother

• Describe the main changes in the different maternal physiological systems

• Discuss the main issues relating to breastfeeding

• Define the different emotional states and be able to identify signs of depression and puerperal psychosis

• Describe the implications for bodywork of these changes

3.1. Definition of postpartum period and overview of changes

It is a matter of debate how long the postnatal period actually is. Traditionally the ‘puerperium’ means the period belonging to the child, and medically it is defined as the 6 weeks following the delivery of the placenta. This is the time during which the pelvic organs return to their normal condition and most of the anatomical and physiological changes of pregnancy and birth are reversed. Many of the changes occur within 10–14 days after delivery. These first few weeks are potentially dangerous. There is the risk of infection due to the open placental site and blood loss. Fever, and in rare cases death, can ensue. There is also a risk of thrombosis developing. (See CEMACH 2006 for UK figures.)

The rate of these changes varies considerably from woman to woman. Recovery depends on the fitness of the mother, her general medical condition pre-, during and post-pregnancy and the kind of birth she has experienced. Recovery from instrumental or surgical delivery is longer as the mother has to recover from the surgery as well as the physiological processes. Some women may experience involution of the uterus within 4 weeks and for some of the systems in the body it can take 10–12 weeks or longer for structures to heal. The changes in the musculoskeletal system are slowest to recover and, if she does not care adequately for herself, the mother may experience long-term patterns of weakness in the areas of the body which had to make the most changes in pregnancy and labour, notably the abdomen, lower back and pelvic floor.

Both immediate and longer-term recovery is dependent on what the mother does, how she looks after herself, the balance she achieves between work and rest. These days, with the increasing demand for mothers to return early to work outside the home, women often have little time to rest and look after themselves and we have yet to see the effects on the long-term health of women of these recent changes in working and childrearing practices.

Midwives’ care (in the UK) for the postpartum period is defined as ‘a period of not less than ten and not more than 28 days after the end of labour, during which time the continued attendance of a midwife on the mother and baby is requisite’ (UKCC 1998). Most northern and western European countries have home-based postpartum visits for up to the first 6 weeks (Kamerman & Kahn 1993). In the Netherlands women receive daily visits from a specially trained helper called the Kraamverzorgester (De Vries et al 2001) and many Chinese mothers have home-based support for the first month (Lee et al 2004). In the USA and Canada postpartum care is less extensive (Cheng et al 2006). A major component of current postnatal care consists of vaginal examination and contraceptive education. One third of women interviewed in a study felt that this was not sufficient and wanted more physical and emotional support and for a longer period (Declercq et al 2002). Postnatal care is being reviewed in many countries and there are recommendations by some that postpartum care could be extended to 1 year (Walker & Wilging 2000).

Many people have argued that the postpartum period should be considered as longer than it has been and include the first year. After 1 year more than 50% of women said they still suffered from fatigue (Saurel-Cubizolles et al 2000).

In many traditional cultures the period of full recovery was considered to be much longer and in ancient Japan and China women were sometimes advised to wait 5–7 years to have another child. Recent research suggests that it is better for women to wait for at least 2 years. Naturally for each mother the recovery will be different, depending on age, number of pregnancies, level of support on so on. It also depends on how long the mother is going to breastfeed. In modern cultures the tendency is more towards 3–6 months, whereas in traditional cultures it was 2–3 years. With the age of childbearing increasing, delaying future pregnancies may not be a viable option but pregnancies close together, especially when older, do tend to place more demands on the mother.

Not only is the body recovering from pregnancy but there are also the changes of labour and initiating lactation, if the mother is breastfeeding. The woman is processing major physical changes, including major hormonal changes which may affect her moods. Emotionally there are also major psychological and social changes to accommodate as she begins to assume care of her new child and integrate him or her into the family system as well as, increasingly these days, to balance work outside the home with family responsibilities. She may also be processing feelings resulting from her labour. The rate of depression at this time is relatively high.

For these reasons, we have chosen here to consider the whole of the first year as the postnatal period. By the end of the first year, the mother is more emotionally stable and longer-term patterns of good or poor health are beginning to be laid down. The completion of the first year often marks the infant’s first steps and the beginning of a new phase of independence for the child. During this year, however, some women will conceive and so then they will be dealing with postnatal and pregnancy changes simultaneously.

For many women, long-term health patterns are poor (MacArthur et al., 1991a and MacArthur et al., 1991b). This could be due to changes in the pregnancy or birth, or to the physical, emotional and lifestyle changes consequent on accommodating a new baby in one’s life. The McArthur et al study, conducted in Birmingham, UK (MacArthur et al., 1991a and MacArthur et al., 1991b) obtained information on the health problems of 11701 women between 1 and 9 years after child birth. One of the main aims of the study was to investigate childbirth-related health problems and so the analysis was restricted to symptoms not previously experienced before the birth and starting within 3 months of it. Almost half the women (47%) reported one symptom which lasted for longer than 6 weeks. There have been other studies (Brown & Lumley 2000, Glazener et al 1995, Kahn et al 2002, Saurel-Cubizolles et al 2000) which have also examined health after birth. The types of symptoms identified are rarely life threatening but can have an effect on the quality of life.

They are also concerning because poor maternal health has been related to poor children’s health (Kahn et al 2002).

Often these changes are not reported to the medical carers. This can be an area where the bodyworker can play a huge role and offer immense support. Postnatal health lays the foundations for a woman’s health for the rest of her life (WHO 1998).

3.2. The female reproductive system

The major hormonal changes of the early postnatal period support rapid changes in the reproductive system. The uterus returns to its pre-pregnant size as early as 4 weeks after a vaginal birth. After a caesarean birth recovery is longer and scar pain may still be felt years later. The pelvic floor recovers within a couple of weeks after a natural birth and up to 4–6 months after an episiotomy. Pregnancy may have a beneficial effect on conditions such as menstrual pain and endometriosis. However, long-term weakness often remains, with stress incontinence and haemorrhoids being common. If the woman is not breastfeeding her breasts return to their normal size and the menstrual cycle will resume within 15 weeks. If the woman is breastfeeding, the breasts will remain altered and fertility will resume usually within 9 months unless nutrition is poor and the mother is feeding frequently. Contraception is an issue as there can be a return to fertility before the first period.

Involution of uterus

Involution means the return of the uterus to normal size, tone and position. During this process the lining of the uterus (decidua) is cast off in the lochia and later replaced by new endometrium. After the birth of the baby and the expulsion of the placenta the muscles of the uterus constrict the blood vessels to reduce the blood circulating in the uterus: vasoconstriction. Oxytocin released from the posterior pituitary induces the strong myometrial contractions. During the first 12–24 hours these contractions (‘after-pains’) are relatively strong, gradually diminishing in intensity and frequency over the next 4–7 days. They tend to be stronger in multiparous women. They can also be stimulated by oxytocin released during breastfeeding.

About an hour after delivery the myometrium relaxes slightly but further active bleeding is prevented by the activation of blood clotting mechanisms which are altered greatly in pregnancy to facilitate a swift clotting response. This is why there is an increase in DVT in the early postpartum period. The primary caregiver will check that there are no ‘retained products’ such as pieces of the placenta, because these may impede the contraction of the uterus and cause abnormal bleeding. They can also cause secondary postpartum haemorrhage as they become the focus of infection.

Redundant muscles, fibrous and elastic tissue have to be broken down. The phagocytes deal with fibrous and elastic tissue but the process of phagocytosis is usually incomplete and some elastic tissue remains so that a once pregnant uterus never totally returns to its nulliparous state. Muscle fibres are digested by proteolytic enzymes in a process known as autolysis. The lysosomes of the cells are responsible for this process. The waste products then pass into the bloodstream to be eliminated by the kidneys.

The decidual lining of the uterus is shed in the lochia. The new endometrium grows from the basal layer, beginning to be formed from around the 10th postnatal day, and is completed in about 6 weeks.

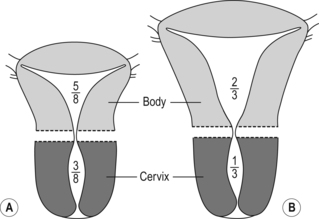

The process of involution takes at least 6 weeks to complete (Fig. 3.1). Immediately after delivery the uterus weighs about 900–1000 g. By 24 hours postpartum the size is similar to its size at 20 weeks (Monheit et al 1980, Resnik 1999). The rate of involution can be assessed by the rate of descent of the uterine fundus. On the first day the height of the fundus above the symphysis pubis is just over 12 cm (Howie 1995). The height of the fundus usually decreases by about 1 cm per day so that by 3 days the fundus lies 2–3 fingers’ widths below the umbilicus, or slightly higher in multigravidas. Primary caregivers feel the uterus each day to note the decrease in size, although the practice of recording and charting the fundal height is decreasing.

|

| Fig. 3.1A and B Return of uterus to size. A is nalliparous; B is parous. |

At about 5–6 days the uterus weighs about 500 g and the cervix is reforming and closing and will admit one finger. Usually by about 10 days the uterus has descended into the true pelvis.

The rate of involution varies from mother to mother and is usually slower in the following cases:

• Multiparous women.

• Multiple gestation.

• Infections.

• Delivery of a large infant.

Involution may be slower if there is retention of placental tissue or blood clot, particularly when this has caused an infection.

Discharge of lochia

Lochia is the name given to the discharge coming from the placental site. The normal pattern is for red discharge in the first 3 or 4 days: lochia rubra or red lochia. It consists mainly of blood mixed with shreds of decidua. This becomes lighter (more brownish) and eventually serous after about 5 or 6 days: lochia serosa or serous lochia. This is altered blood and serum and contains leucocytes and organisms. The final discharge is known as lochia alba, yellowish-white lochia, in which there is little blood. It is mostly white blood cells, cervical mucous and organisms. Discharge decreases in amount as the site heals. The average time for lochia to become colourless is about 3–4 weeks.

Lochia that remain red and abundant for longer than usual may indicate delayed involution of the uterus, which may be due to retention of a piece of placenta within the uterus and/or to infection. If placental tissue is retained the uterus remains enlarged and this may show on an ultrasound scan. Lochia with offensive odour may indicate infection. It is possible for red lochial discharge to still be present at 6–8 weeks. It is more common also after instrumental delivery. Seek medical help if concerned.

Cervix, vagina, ligaments and pelvic floor

The vagina, the ligaments of the uterus and the muscles of the pelvic floor also return to their pre-pregnant state. If the ligaments and pelvic floor do not return and are permanently weakened, a prolapse may occur later. Pre-pregnancy fitness is a factor in supporting the strength, as is fitness during pregnancy and postnatal exercises as well as avoiding constipation and coughing.

Cervix and vagina

After a vaginal delivery the cervix hangs into the vagina and is thin, bruised and oedematous with multiple lacerations. Over the next 12–18 hours it shortens and becomes firmer. During the first 2–3 days it is dilated 2–4 cm and two fingers can be inserted into the cervical os. By 1 week barely a finger can be inserted. By 4 weeks it is a slit (as opposed to a circle in women who have had no children).

The vagina is also oedematous with decreased tone but its epithelium is generally restored by 6–10 weeks (Monheit et al 1980, Resnick 1999).

Ovaries and uterine tubes

These become pelvic organs again. Following the delivery of the placenta, oestrogens and progesterone fall. Eventually negative feedback mechanisms trigger off the ovarian menstrual cycle.

The perineum

The perineum has to recover from stretching during birth and can be damaged during delivery as well as the stretching and additional work of pregnancy. Even after a caesarean, recovery and rehabilitation is necessary.

It is common to feel some soreness in the first few days but some women experience more intense pain. This can be relieved by the use of icepacks. However, especially after deeper tearing and stitches, more pain relief may be needed and women may need to be referred back to their primary caregiver to be prescribed oral analgesics such as paracetamol.

It is important for the mother to exercise the muscles, even if only very gently, within 24 hours of delivery, to promote blood circulation and strengthen the tissue. Pelvic floor exercises need to be gradually increased as the muscles heal, and carried on for the rest of the mother’s life. If there is extensive damage she may need to see a physiotherapist and use ultrasound therapies to rehabilitate the muscles (Glazener et al 1995).

Episiotomies were once thought to limit perineal pain by limiting tearing. However, the most recent studies (Carroli & Belizan 2001) showed that there is little evidence to justify this.

Perineal damage

Types of perineal tear

These are classified according to the severity:

• Superficial – grazes, no treatment, a bit sore.

• First degree – tear in skin, often will heal on its own.

• Second degree – skin tears involve perineal muscle damage; usually these wounds are sutured.

• Episiotomy – a surgical incision falling into same category as second degree tear.

• Third degree – here the muscle of the anal sphincter is involved. Obstetric repair is essential so that the sphincter activity of the muscle is restored, thus avoiding problems of faecal incontinence at a later time.

• Fourth degree – when the tear is extensive and the anal sphincter may become completely divided and the tear continues through the rectal mucosa. Specialist surgical repair is required to ensure the resumption of normal anal function.

Damage to the perineum is associated with problems such as pain, infection, alterations in urination, faecal problems including incontinence, third degree laceration and dyspareunia (painful intercourse) (Brown & Lumley 2000, Glazener et al 1995). Initial healing takes about 2–3 weeks but the site may take 4–6 months to heal completely.

Mammary changes

In women who do not breastfeed, breast involution occurs. With no stimulation by suckling, prolactin levels decrease, milk production ceases and glandular tissue returns to a resting state over the next few weeks. Cold flannels can be used on the breast of non-lactating women to reduce the flow of colostrum. For women who breastfeed many changes occur in the breasts in the early postnatal period.

Physiology of lactation

Breastfeeding and fertility

Breastfeeding delays the recovery of the ovarian–pituitary axis. In non-breastfeeding women body temperature measurements and the first menstrual bleeding suggest that the earliest ovulation may occur at 4 weeks after delivery but is usually delayed to 8–10 weeks (Gray et al 1987). Most non-breastfeeding women have resumed normal menstrual patterns by 15 weeks. The first menstrual cycle is often anovulatory or associated with an inadequate luteal phase, but most cycles are ovulatory by the third cycle. About 50% of non-lactating women who do not use contraception conceive within 6–7 months so contraception needs to be discussed (Coad & Dunstall 2001: 357).

In lactating women menstruation and ovulation return more slowly. Lactational amenorrhoea may last from 2 months to 4 years and its variability seems related to a number of factors, of which the most important is frequency of feeding. In developing countries breastfeeding prevents more pregnancies than all other methods combined. Night-time feeds seem important in suppressing fertility (Howie & McNeilly 1982). Poor nutrition also suppresses fertility when combined with longer breastfeeding patterns (Rogers 1997). Women who have less optimal nutrition can breastfeed their babies but they secrete milk more slowly so infants feed more often and for longer, raising circulating prolactin levels.

Ovarian activity usually resumes before the end of lactational amenorrhoea and so conception can occur before the resumption of menstruation. Between 30% and 70% of first cycles are ovulatory. Neither ovulation nor menstruation usually occur within 6 weeks but about half of all non-contraceptive-protected breastfeeding mothers conceive within 9 months, 1–10% during lactational amenorrhoea.

The precise mechanisms involved in lactational amenorrhoea are not clear but it is due to high prolactin levels blocking the effects of luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and it may possibly affect libido.

Sexual function

Resumption of sex can be uncomfortable for women, especially after an instrumental delivery, such as episiotomy or caesarean section, as there can be pain in the scars. Both emotionally, as well as physically, it may take several months for the mother to feel comfortable having sex again. In some cultures and religions there are taboos on having sex for the first few months.

Some mothers may not feel comfortable with sex for longer after a birth, even a year later, and this may create tension in their relationships.

Lack of oestrogen can aggravate the pain and the use of topical oestrogens may be advised.

• Lochial discharge: be aware during the first 4–6 weeks to ask if there is still lochial discharge.

• While there is lochial discharge, work on the abdomen should be more gentle and care needs to be taken with exercises to not place too much pressure on the abdomen and there is an increased risk of infection.

• Refer if there is any concern re abdominal or pelvic floor pain or bleeding (lochial discharge or discharge from incisions).

• Note that after-pains may be experienced in the first few days, which may cause discomfort for the mother. Abdominal work will need to be adjusted accordingly.

• Sexuality: women may want to talk about their feelings about sex, which is often an issue: e.g. when to have sex, feelings about not wanting sex, the changes in the relationship with partner. While not being sexual counsellors, it may be helpful for bodyworkers to allow the woman space to express her feelings.

• Note that menstruation is not an indicator of fertility and the mother needs to be aware of contraceptive issues and be referred for appropriate follow-up.

Referral issues

• Refer if there is any concern over bleeding or pain, tenderness over the uterus.

• Be alert to any signs of possible infection in the first few weeks and refer to the primary caregiver.

3.3. Neuroendocrine system

Major and rapid changes happen in the hormone levels and many postulate that depression can be in part explained by this. As hormones have both blood and neural pathways they will impact on the mother’s physical and emotional state of being.

Changes occur mostly after birth with the delivery of the placenta and due to changes in prolactin secretion. In general most peptide hormones, enzymes and other circulating proteins reach non-pregnant levels by 6 weeks postpartum.

If the mother is breastfeeding then the two most important hormones are prolactin and oxytocin and her hormone levels remain different from the non-lactating and pre-pregnant woman. These hormones aid with bonding and relaxation and support the process of breastfeeding.

Oestrogens and progesterone

As the placenta is the main source of oestrogens and progesterone, they tend to disappear rapidly following delivery. Plasma oestradiol (an oestrogen) reaches levels that are less than 2% of pregnancy values by 24 hours.

By 1–3 days oestradiol levels are similar to those found during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle and oestrogen levels continue to fall until day 7, when they gradually increase to follicular phase levels over the next few weeks.

Progesterone levels fall rapidly at delivery (Dooley 1984). Generally progesterone levels similar to those found in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle are reached by 24–48 hours and follicular phase levels by 3–7 days. Ovarian production of oestrogen and progesterone is low during the first 2 weeks. The levels gradually increase with the resumption of gonadotropin secretion by the pituitary and ovary (Liu & Yen 1989, Tulchinsky 1994).

These rapid changes are likely to affect mood swings.

Pituitary gonadotropin

This is suppressed during pregnancy. FSH and LH remain low during the first 2 weeks postpartum in both lactating and non-lactating women then gradually increase over the next few weeks, more quickly in non-lactating women.

Prolactin and oxytocin

These are the two main hormones which regulate breastfeeding (Table 3.1).

| TSH = thyroid stimulating hormone; VIP = vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. | ||

| Prolactin | Oxytocin | |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Anterior pituitary gland | Posterior pituitary (synthesised in hypothalamus) |

| Primary control | Lifting of dopamine inhibition | Neural pathway |

| Modulating factors | Positively stimulated by oestrogen, TSH, VIP | Neurotransmitters |

| Peak response | 30 min | 30 s |

| Stimulus | Suckling | Suckling, sound, sight and thought of baby |

| Target cell | Alveolar cell | Myoepithelial cell |

| Effect | Milk synthesis | Milk ejection |

Prolactin

Its levels are increased during pregnancy, although its effects are suppressed by oestrogen. During pregnancy it promotes the development of the mammary alveoli and duct system in preparation for breastfeeding. Its levels vary diurnally and increase during sleep. It increases with stress, anaesthesia, surgery, exercise, nipple stimulation and sexual intercourse (Lawrence & Lawrence 1999).

As labour begins prolactin levels fall, increasing immediately after delivery and peaking about 3 hours postpartum. Postnatally its secretion is triggered by the newborn suckling. In non-lactating women levels fall by 7–14 days to the high end of the non-pregnant range.

If the newborn suckles then levels of prolactin begin to rise within 10 minutes. They result in a complex neuroendocrine response. Levels peak about 30 minutes after initial stimulation and fall back to basal levels within a further 3 hours. Areolar stimulation is necessary for prolactin release.

Levels of prolactin are much diminished after 6 weeks at a rate dependent on suckling frequency and duration (Johnston & Amico 1986). There are higher circulating levels during sleep.

Oxytocin

Oxytocin is probably the main hormone which promotes ‘mothering’ feelings and emotions as well as supporting breastfeeding. Odent refers to it as ‘the Love hormone’ (Odent 2001, Pederson et al 1992). Uvnäs-Moberg (2003) refers to it as ‘the hormone of calm, love and healing’, the mirror hormone of adrenaline, the ‘calm and connection system’. It is linked with intimacy and communication, bonding.

Oxytocin increases during labour. It plays a critical role in the ejection of milk. Putting the infant to breast immediately after delivery many enhance uterine involution (Neville & Neifert 1983). These ‘after-pains’ are experienced as a cramping pain in the abdomen. They usually only last for a few days and seem to be worse if the mother has received syntometrine and with each subsequent pregnancy.

After a caesarean there are less oxytocin impulses. It is not known if this is due to the mode of birth, the effects of delayed skin-to-skin contact, the pain and stress caused by surgery, or the effects of anaesthesia and analgesics (Nissen et al 1996).

Oxytocin helps the body store nutrients and promotes the differentiation and effectiveness of the body’s storage systems. There has to be a balance in the body between nursing and the conservation of energy for the mother. This explains why some nursing mothers lose weight and others gain.

The milk ejection reflex is responsible for transfer of milk from the breast to the baby. It is independent from prolactin. It is released in short-lived bursts of less than a minute immediately in response to stimulus. The largest response is to the baby crying before feeding so maximum release is likely before suckling is started. Covering breasts and use of warm flannels can help with the release of oxytocin.

Unlike prolactin it can be conditioned. It is produced by continuous physical contact with the child and sensitive to inhibition by physical or psychological stresses such as emotional tiredness, embarrassment and worry. The limbic system which coordinates the body’s response to emotions is involved in oxytocic release.

• It is common for the mother to feel emotional in the first week or two due to the huge changes in oestrogens and progesterones in addition to the life changes she is undergoing.

• Be aware of how breastfeeding mothers release high levels of oxytocin – the love hormone. This may help explain why breastfeeding mothers can find the adaptation to the postnatal period easier.

• The tissue remains soft in the early postnatal time as relaxin levels are still quite high.

It helps maintain a state of calmness and relaxation. Blood pressure can drop and cortisol levels drop. More seems to be released during sleep.

Relaxin

Levels fall rapidly after delivery but significant amounts remain for the first 6–8 weeks postnatally. It is still important to be aware of laxity in the pelvic girdle postnatally.

Thyroid

The enlarged thyroid gland regresses to its former size and the basal metabolic rate returns to normal.

3.4. Haematological, haemostatic and cardiovascular systems

The major changes in these systems happen in the first few weeks. The hypercoagulable state of pregnancy is increased in the early postnatal period and during the first 6 weeks the risk of thromboembolic disorders is high. Changes in these systems can lead to an increased risk of infection due to the placental wound site and the lochia, which provides ideal culture conditions for micro-organisms. There is additional risk with instrumental deliveries and the extra incision. Anaemia can also be a cause of infection. Further, the mother can be prone to anaemic conditions if she does not eat adequately, especially if she is breastfeeding.

Haemostasis

There are some changes in the haemostatic system during labour itself, in order to prepare the woman to tolerate the normal blood loss at delivery and prevent significant bleeding with the separation of the placenta. Haemoglobin levels increase slightly during labour and concentrations of clotting factors also increase. This means that the hypercoagulable state of pregnancy is increased in the early postnatal period, in order to protect the mother from haemorrhage and excessive blood loss.

Blood loss

Blood loss at delivery averages around 500 ml with vaginal delivery and 1000 ml with caesarean section or twins. It is more than compensated for by the increase in blood volume in pregnancy. This loss, along with the lochial discharge of the early weeks, accounts for about half of the increased RBC volume acquired during pregnancy (Chesley 1972).

Plasma volume decreases, reaching non-pregnant levels by 6–8 weeks or earlier (Chesley 1972). Increased RBC production ceases early postpartum and means haemoglobin levels decrease slightly in the first 24 hours after delivery and then rise to day 14. Haematocrit values follow a similar pattern and return to non-pregnant levels by 4–6 weeks. However, haemoglobin levels tend to be low postnatally even though they are not routinely tested. As many as 7% of women with no previous low HB have anaemia between 2 and 18 months after birth (Glazener et al 1993). This will contribute to the feelings of tiredness commonly experienced by women.

WBC increases in labour and the immediate postpartum then falls and returns to normal value by 6 days and can complicate diagnosis of infection (Kilpatrick & Laros 1999).

Fibrinolytic activity is maximal for the first 3 hours after delivery although it may return to normal ranges as early as 1 hour and reflects the removal of the fibrinolytic inhibitors produced by the placenta. Clotting factors slowly decrease reaching their lowest levels by 7–10 days. The haematological system returns to its non-pregnancy state 3–4 weeks postpartum. Changes in flow velocity and diameter of the deep veins may take up to 6 weeks to return to pre-pregnant levels. This means that during the first 6 weeks the risk of thromboembolic disorders is high (Hathway & Bonnar 1987).

Thromboembolic disorders

These represent some of the major causes of maternal death.

DVT: risk of thrombosis

Mobilisation after birth is essential to optimise venous return in order to avoid stasis within the vascular bed and reduce the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) formation. Women who are unable to mobilise or at increased risk, owing to obstetric complications such as a lower segment caesarean section (LSCS), are given prophylactic anticoagulant treatment. Women are encouraged to report any discomfort or swelling of the lower legs as this may indicate DVT formation. It has been observed clinically that there is an increased risk of DVT in the left leg especially after caesarean section because blood flow velocity is reduced to a greater extent. Intimal vessel injury (damage to the inner lining of the vein injury) may occur during caesarean section delivery which could conceivably trigger a pelvic vein thrombosis.

Risk factors

Risk factors include: increased maternal age, parity, dehydration following delivery and delivery by caesarean section, previous history of thromboembolic problems, pregnancy-induced hypertension, artificial heart valve, operative delivery (Weiner 1985).

Pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is an obstetric emergency that may arise in the postnatal period as well as pregnancy and though rare, it is one of the main causes of maternal death.

Cardiovascular system

Despite the amount of blood loss, cardiac output is significantly elevated above pre-labour levels for up to 1–2 hours postpartum (Pritchard et al 1962). There are minimal changes in blood pressure and pulse. Stroke volume and cardiac output remain elevated for at least 48 hours after delivery, probably due to increased venous return with loss of uterine blood flow. Cardiac output decreases by 30% by 2 weeks postpartum and gradually decreases to non-pregnant values by 6–12 weeks in most women. Most of the other changes in the cardiovascular system resolve by 6–8 weeks postpartum. Left atrial size and heart rate reach pre-pregnancy values by 10 days postpartum. For 20% of women there is a systolic murmur which persists beyond 4 weeks postpartum.

Blood loss, and the mechanisms which compensate for it, render the cardiovascular system transiently unstable after delivery. During the first week after delivery, many women experience headaches due to this unstable fluid balance. Vascular remodelling persists for at least a year after birth and is enhanced by second and subsequent pregnancies (Clapp & Capeless 1997). This means stroke volume remains relatively high, causing reduced heart rate. It is normal for puerperal women to exhibit a reduced pulse rate. A raised pulse may indicate severe anaemia, venous thrombosis or infection.

During the first week after delivery there is an increase in diuresis which needs to happen in order to dissipate the increased extracellular fluid. Sometimes with women in pre-eclampsia or heart disease there may be no diuresis and so pulmonary oedema can result.

Blood volume returns to its pre-gravid levels and blood regains its former viscosity. Smooth muscle tone in the vessel walls improves and cardiac output returns to normal and the blood pressure to its usual level.

Varicose veins

These often regress after pregnancy, but usually become worse with each successive pregnancy and can become permanent.

• Most of the blood changes are in the early period (6–8 weeks).

• There is a possibility of infection in the early weeks while wound healing occurs, e.g. bleeding from vagina, from caesarean section scar.

• There is an increased risk of thrombosis in the first 6 weeks, especially the first week or so. Encourage mobilisation.

• Tiredness can be due to anaemia rather than simply sleep deprivation and stress.

• There is an increased incidence of varicose veins in women who have had children.

• Raised pulse may indicate severe anaemia, thrombosis or infection.

Referral

• Infection.

• Raised pulse.

• Oedema.

• Fever.

3.5. Musculoskeletal system

These systems take longest to recover and without appropriate exercises and self-care, some weakness may remain long term. While some women regain their fitness and health levels quickly, especially after one pregnancy, for others pregnancy can signal the beginning of patterns of weakness. If the weakened abdominal wall and pelvic floor are not exercised, then this may cause weakness in the pelvic area, leading to lack of support for the internal organs as well as problems with the lower back. Issues with pelvic girdle weakness overlaid on a body which is feeding and lifting young children often cause imbalance in the hip and the shoulders. The softness of the tissue can remain for a few months postnatally, especially if the mother is still breastfeeding as prolactin levels couple with relaxin and maintain the softened tone.

The multiparous breastfeeding mother may have ongoing pubic symphysis instability, anterior uterine strain as ligaments are engorged, coupled with increased lumbar lordosis for several months. There may also be adhesions within the abdominal and pelvic cavities due to the fascial stretching during pregnancy, and so postpartum resolution may take the first 12 months to clear if breast feeding.

(A. Morgan, personal communication, 2008)

Sometimes this muscular weakness, especially in the pelvis, can be triggered during the menstrual cycle.

Pelvic floor

Due to stretching during birth, these may be bruised or swollen and tender to pressure both externally (thighs, buttocks) or internally (coughing, laughing or sneezing). If there has been instrumental delivery, then there will be a need to recover from stitches. Previously it was thought that episiotomy was ‘better’ than a tear but now it is understood that torn tissue heals better, as it can knit together better. Most women suffer from some degree of tearing of the perineum.

After caesarean births women can have pelvic floor dysfunction as much as women who have experienced vaginal births because a lot of the additional strain on the pelvic floor is sustained during pregnancy.

Pelvic floor exercises help to pump blood back to the area and aid healing. Exercise can gradually become more intense. Long-term strength and support will help prevent issues such as stress incontinence and haemorrhoids. Bladder control can be improved (Cardozo & Cuter 1997) and the uterus supported, reducing the incidence of prolapse. Other benefits of strengthening pelvic floor muscles may be to help the mother feel more at ease with that area of her body and help in resuming sex. Sex in turn is good for the pelvic floor.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree