A 45-year-old ex-ballerina presents with a painful great toe and dorsal swelling as shown in Figure 14.1.

1 This patient had virtually no movement at her MTP joint. What terms are used to describe restricted movement at the first MTP joint?

2 Young patients with this condition often report that they have participated in competitive sport. Which sports are particularly bad for your toe and what other conditions will lead to the radiographic appearances shown in Figure 14.2?

|

| Fig. 14.2 |

3 What functional variations may predispose a patient to this condition?

4 Outline an appropriate grading system.

5 What conservative treatments might lessen this patient’s pain?

|

| Fig. 14.1 |

Hallux limitus/rigidus (aetiology/conservative management)

2 Degenerative joint arthritis arises from direct cartilage damage, and players of any sport who kick a ball repetitively are prone to hallux rigidus. In American footballers the condition is labelled ‘turf toe’. Sepsis, inflammatory arthritis or excessive repetitive weight transfer (a similar factor to that causing osteochondritis of the second metatarsal head) all potentially lead to the same end result.

3 Metatarsus elevatus and first ray hypermobility, as occur secondary to abnormal stance phase pronation, are reportedly associated with an increased risk of acquiring hallux rigidus, although empirical data in support of these theories are lacking.

4 A number of grading systems are available for hallux rgidus. A five-point scoring system is provided in Table 14.1.

| Grade | Dorsiflexion | Radiographic findings | Clinical findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 40–60° and/or 10–20% loss compared with normal side | Normal | No pain: only stiffness and loss of motion on examination |

| 1 | 30–40° and/or 20–50% loss compared with normal side | Dorsal osteophyte is main finding, minimal joint space narrowing, minimal periarticular sclerosis, minimal flattening of metatarsal head | Mild or occasional pain and stiffness, pain at extremes of dorsiflexion and/or plantarflexion on examination |

| 2 | 10–30° and/or 50–75% loss compared with normal side | Dorsal, lateral and possibly medial osteophytes giving flattened appearance to metatarsal head, no more than ¼ of dorsal joint involved on lateral radiograph, mild to moderate joint space narrowing and sclerosis, sesamoids not usually involved | Moderate to severe pain and stiffness that may be constant: pain occurs just before maximum dorsiflexion and maximum plantarflexion on examination |

| 3 | ≤10° and/or 75–100% loss compared with normal side. There is notable loss of MTP plantarflexion as well (often ≤10° of plantarflexion) | Same as in grade 2 but with substantial narrowing, possibly periarticular cystic changes, more than ¼ of dorsal joint space involved on lateral radiograph, sesamoids enlarged and/or cystic and/or irregular | Nearly constant pain and substantial stiffness at extremes of range of motion but not at mid-range |

| 4 | Same as in grade 3 | Same as in grade 3 | Same criteria as grade 3 but there is definite pain at mid-range of passive motion |

5 Two factors produce symptoms and it may be important to address one or both of these. Firstly, as osteoarthritis of the MTP joint progresses, the joint space narrows, which leads to tendon and ligament contractures and associated stiffness. Secondly, osteophytes form around the margins of the joint, particularly dorsally and laterally, leading to a mechanical block to extension and sometimes hallux flexus.

Transient benefits may be gained from simple conservative treatments. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, rest and elevation of the foot may all help if the toe is particularly sore. Intra-articular steroid injections provide short-term pain relief, but a rigid insole should restrict joint movement sufficiently to lessen pain (Fig. 14.3). A rocker on the sole is also worth fitting as this acts to offload the first metatarsal head by reducing the need for joint extension at ‘toe-off’ (Fig. 14.4). If these treatments fail, then patients will generally consider surgery.

|

| Fig. 14.3 |

|

| Fig. 14.4 |

Key Points

• Hallux limitus/rigidus is a degenerative condition.

• Painful joint extension prevents normal gait.

• A scoring system is available to aid decision making.

• In-shoe orthoses should be considered in grade I or grade II hallux limitus/rigidus.

• A rocker sole may be helpful.

Further reading

Coughlin, MJ; Shurnas, PS, Hallux rigidus. Grading and long term results of operative treatment, Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 85-A (11) (2003) 2072–2088;

Horton, GA; Park, Y-W; Myerson, MS, Role of metatarsus primus elevatus in the pathogenesis of hallux rigidus, Foot and Ankle International 20 (1999) 777–780.

Smith, RW; Katchis, SD; Ayson, LC, Outcomes in hallux rigidus patients treated nonoperatively: a long-term follow-up study, Foot and Ankle International 21 (2000) 906–913.

Solan, MC; Calder, JD; Bendall, SP, Manipulation and injection for hallux rigidus. Is it worthwhile? Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 83-B (5) (2001) 706–708.

Case 15

A distinctive bony prominence has developed overlying this lady’s second metatarsal head (Fig. 15.1). She is 61 years old, retired and has a long-standing history of pain in her right foot. On examination, movement at her MTP joint was severely restricted.

1 Given the objective symptoms, explain the presence of this dorsal prominence.

2 Does this condition only occur in adolescents?

3 Describe the pathology of the condition.

4 Do conservative measures have anything to offer this patient?

5 What are the surgical options?

Freiberg’s infraction

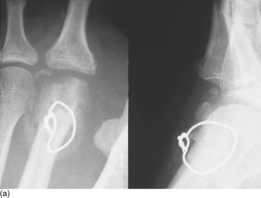

2 No. Most of the literature describes the cause as an insult to the blood supply of the open epiphysis of the metatarsal head. However, Figures 15.2a and 15.2b show radiographs of a 64-year-old man taken 4 years ago for a coincidental injury and then this year for recent forefoot pain. Clearly this shows the development of a ‘new Freiberg’s’ and is evidence that avascular necrosis of the metatarsal head can occur in later life.

3 The head of the metatarsal progressively collapses or ‘infracts’ into the avascular segment (Fig. 15.3). This leads to flattening of the metatarsal articular surface, head compression and loss of joint space. The later changes are those of secondary osteoarthritis (Fig. 15.4). The classic description of the pathology of Freiberg’s was provided by Smillie In 1967 and the five stages are summarized in Table 15.1.

| Stage 1 | A fissure fracture develops in the ischaemic epiphysis |

| Stage II | Absorption of bone has taken place and the central portion begins to sink into the head, altering the contour of the articular cartilage |

| Stage III | Further absorption has occurred and the central portion sinks into the head leaving projections on either side. The plantar articular cartilage remains intact. |

| Stage IV | The plantar isthmus of articular cartilage has given way and the loose body separated. Fractures of the lateral and dorsal projections have occurred. Restoration of the anatomy is no longer possible. The epiphysis is probably closed at this stage. |

| Stage V | Final stage of flattening, deformity and arthrosis. |

4 A rocker sole (Fig. 14.4) may be advantageous as it will aid dorsiflexion of the foot. Local injections of corticosteroid provide only short-term symptomatic relief.

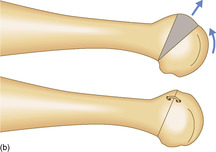

5 In the older patient, where degenerative changes are the cause of discomfort, either a proximal hemiphalangectomy or, as in this case, a joint replacement arthroplasty will be required (Fig. 15.5). In younger patients, Gauthier’s procedure restores joint congruity by rotating the ‘normal’ dorsal cartilage onto the articulating surface (Fig. 15.6).

|

| Fig. 15.5 |

Key Points

• The condition is an avascular necrosis of the metatarsal head.

• Secondary osteoarthritis always develops.

• In older patients, replacement or resection arthroplasty may be necessary.

Further reading

Hay, SM; Smith, TWD, Freiberg’s disease: an unusual presentation at the age of 50 years, The Foot 2 (1992) 176–178;

Smillie, IS, Treatment of Freiberg’s infraction, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 60 (1967) 29–31.

Smith, TWD; Stanley, D; Rowley, DI, Treatment of Freiberg’s disease: a new operative technique, Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 73-B (1991) 129–130.

Townshend, DN; Greiss, M, Total ceramic arthroplasty for painful, destructive disorders of the lesser metatarso-phalangeal joints, The Foot 17 (2) (2007) 73–75.

Case 16

Hammer toe

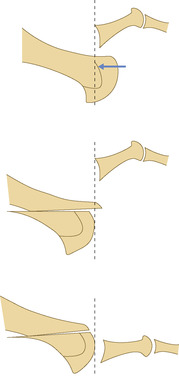

1 The photograph shows the typical appearance of hammering of the second toe. It is potentially serious, particularly if healing is compromised as shown in Figure 16.2. This condition is distinguishable from claw toe (Fig. 16.3) in which there is greater flexion of the distal interphalangeal (IP) joint and dorsal subluxation of the MTP joint. In mallet toe the distal IP joint only is flexed (Fig. 16.4).

|

| Fig. 16.2 |

|

| Fig. 16.3 |

|

| Fig. 16.4 |

2 PIP joint fusion is probably the most commonly performed surgical procedure for hammer toe. Articular cartilage is removed from the head of the proximal phalanx and from the base of the middle phalanx and the surfaces apposed. The fusion is held with a fine Kirschner wire or a biodegradable pin. Hohman has recommended excision of the head of the proximal phalanx and reefing of the dorsal extensor tendon only. We have generally found that this produces an inferior result to fusion, as some patients will experience continuing discomfort from the mobile joint. Hemiphalangectomy (Fig. 16.5) may leave a redundant and shortened digit and amputation produces gapping which in the case of the second toe will cause the hallux to move across into valgus (Fig. 16.6).

3 Pain elicited at the MTP joint on ‘drawing’ the toe dorsally on the metatarsal will signify joint instability. Resection of the IP joint does produce a relative lengthening of the dorsal extensor tendon that may be sufficient to prevent subluxation of the proximal phalanx dorsally on the metatarsal. If not, it is worthwhile performing a dorsal capsulotomy of the MTP joint and possibly also a transfer of the dorsal extensor tendon to the flexor below the metatarsal head. If this is still inadequate then a Weil’s sliding osteotomy may be required (Fig. 16.7 and Fig. 16.8).

|

| Fig. 16.7 |

4 After PIP joint arthrodesis it is worthwhile prescribing a metatarsal dome insole to support the second metatarsal head (Fig. 16.9).

|

| Fig. 16.9 |

Key Points

• Operative treatment is generally beneficial.

• PIP joint fusion is probably the most common procedure performed.

• A metatarsal dome support may be helpful.

Further reading

American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons, Hammer toe syndrome, Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery 38 (1999) 166–178;

Harmonson, JK; Harkless, LB, Operative procedures for the correction of hammer toe, claw toe, and mallet toe: a literature review, Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery 13 (1996) 211–220.

Trnka, H-J; Gebhard, C; Muhlbauer, M; Ivanic, G; Ritschl, P, The Weil osteotomy for treatment of dislocated lesser metatarsophalangeal joints: good outcome in 21 patients with 42 osteotomies, Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica 73 (2002) 190–194.

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue