CHAPTER 2. Western approach to labour

Introduction

‘Labour’ is the process by which the fetus is born. It is variable in its onset and duration for each woman. Term pregnancy is defined as 37–42 weeks. Dating by last monthly period (LMP) alone provides a reasonably accurate indicator of the length of gestation; however, an early ultrasound scan has been shown to provide a more accurate expected date of delivery (Crowley 2003).

There is an increased likelihood of neonatal complications if the fetus is born either earlier or later than this timeframe (RCOG 2001a). While most fetuses born after 42 weeks will be perfectly healthy, some may experience complications during the birthing process and primary care providers face complex situations in deciding whether to induce labour. Supporting ‘nature’ to take its course versus utilisation of medical intervention is also complex, and decisions occur in the context of many factors including the training and attitudes of the individual care provider and their team, the environment where the birth is taking place, and current obstetric policies and trends.

Due to increased technology, babies can now survive delivery at an earlier gestational age. Ethical issues arise in determining the appropriate antenatal and birthing care for a baby born in the range of 23–32 weeks, and decisions relating to the pregnancy and birth are made by parents in consultation with neonatal and perinatal specialists. Along with mortality concerns, there are short- and long-term consequences for an infant born in these earlier timeframes (McGrath et al 2000).

As well as considerable variation in the length of gestation, there are also variations in both the process and the length of labour. The duration of labour can vary from as little as 45 minutes or less to days.

Since the Second World War, there has been an increased medicalisation of the birthing process, and today most labours include various forms of medical care (Downe et al 2001, Department of Health 2005). Some of the interventions improve both maternal and fetal health and save lives and this is reflected in decreased maternal mortality rates in many countries. Medicine has helped women with pre-existing medical conditions in succeeding in bringing their pregnancy to term. However, this means that these women are more likely to need medical intervention. Increasing infertility, age and obesity rates also add medical complexity to pregnancies.

However, there is concern, even within the medical community, that medical care during pregnancy and birth has led to the utilisation of practices which may not improve maternal or fetal outcome. Sometimes, standards of care which may be relevant in a higher-risk pregnancy may be over-utilised in lower-risk situations. The current high mortality rate in some countries may be best addressed through appropriate support with issues such as nutrition and basic health care rather than increased use of technology (Wagner 1994).

Some practitioners have expressed concern that the process of birth, which for healthy women and babies should be essentially a ‘natural’ process, is being unnecessarily interfered with and that the natural variability of labour is becoming lost.

There is considerable need for ongoing research into the effects of specific practices such as the rise of caesareans, and commitment to such research presents challenges for everyone involved in the perinatal community. ‘There is an urgent need for a systematic review of observational studies and a synthesis of qualitative data to better assess the short and long-term effects of caesarean section and vaginal birth’ (Lavender et al 2006). Bodies of knowledge such as the Cochrane Database help to inform and challenge existing maternity care.

The importance of providing encouragement, and continuous emotional and physical support for women in labour has received worldwide recognition:

Given the clear benefits and no known risks associated with intrapartum support, every effort should be made to ensure all labouring women receive appropriate support, not only from those close to them but also from specially trained caregivers. This support should include continuous presence, the provision of hands-on comfort, and encouragement.

This has led to an increased focus on the importance of midwifery care for lower-risk birthing women, and the existence of the growing field of labour support provision or doula care.

The ultimate responsibility for ensuring the woman and infant’s health in labour lies in the hands of the maternity care provider, whether obstetrician, family physician or midwife. They make all medical decisions concerning their patient, while ideally providing them with information which underscores informed choice. Respect for this reality is crucial. It is also important that bodyworkers understand current medical practice and its effect on their pregnant and birthing clients and differing variations in different countries.

Even the generic term ‘maternity care provider’ has different connotations. For example, in countries such as the UK and Holland, midwives tend to be the primary maternity care providers for uncomplicated births, while in the USA and Canada, maternity care is most commonly provided by obstetricians regardless of the status of the woman’s health history.

2.1. Physiological basis of labour

What starts labour?

There is no definitive answer to this question. What is known is that the onset of labour is a complex response triggered by hormones released by both the woman and the fetus. For the fetus, these hormonal changes are related to the maturation of the fetal hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal system. For the woman, levels of utero-tonic inhibitors decrease (the ratio of progesterone goes down while oestrogen, oxytocin and contraction association proteins (CAPs) increase). CAPs include gap junction proteins which allow the transfer of current carrying ions in labour. The position of the fetus also seems to be a factor in supporting the onset of labour and it is thought that a poorly positioned fetus may be a factor in contributing to delayed onset of labour.

Changes in the cervix

At the beginning of labour the cervix of a nulliparous women is usually a thick-walled canal of at least 2 cm in length. The cervix may, however, shorten and dilate before the onset of labour. This process is known as ‘cervical ripening’ and caregivers assess it using the Bishop score (1964) which rates:

• Cervical dilatation (from closed to 3+cm).

• Cervical consistency (from firm to soft).

• Length of cervix (from 3 cm to 0 cm, as it shortens in labour).

• Position of cervix (from posterior to anterior).

• Station of the presenting part (usually the head of the fetus) (from −3 above ischial spines to 0).

There can be a ‘bloody show’. This is when the mucous plug from the cervix is discharged. It is a mucousy, slightly bloody vaginal loss. This can happen a couple of days or weeks before labour begins, or during early labour itself.

The first contractions begin by stretching the lower segment of the uterus but the lower part of the cervical canal is initially unaltered. As labour progresses, the internal os is pulled open and the cervix dilates from the top downwards. It becomes shorter until no projection into the vagina is felt but only a more or less thick rim at the external os, the whole cervix being taken up and its cavity made one with that of the body of the uterus.

Prelabour

There are nearly always prelabour contractions which may or may not be perceptible to the woman. These prepare the woman and fetus for labour. They shape the cervix, help with the positioning of the fetus, may begin the process of effacement, and in multiparous women, sometimes the process of dilatation. Many nulliparae will feel prelabour contractions when the fetus engages. In multiparae it is not unusual for the fetus to engage at the onset of or during labour.

Rupture of the membranes

This may occur prior to labour or at any stage in labour, although it usually occurs towards the end of first stage. As the cervix starts to efface and the fetal head descends on to the cervix, the small bag of waters in front of the head (the forewaters) is separated from the remainder (the hindwaters). The forewaters help the early effacement of the cervix and dilatation of the os uteri. The hindwaters help to equalise the pressure in the uterus during uterine contractions and provide some protection to the fetus and placenta.

Changes in the uterus and the mechanism of contractions

All stages of labour are characterised by contractions of the uterus, which are slightly different for each stage of labour. A contraction is an experience which feels different for each woman. Some feel latent labour contractions intensely, others feel only slight discomfort. Some may not even be aware of contractions at all other than a hardening of the abdomen. Usually as labour progresses most women do feel their contractions and experience intense sensations, although a minority of women do not feel them much at all.

How contractions begin varies from woman to woman. Some women enter labour with strong contractions while other women have days of lighter contractions or perhaps several hours of strong contractions and then nothing for hours. It is not uncommon for multiparae to experience uterine contractions which are strong enough to be painful for some days or even weeks before real labour starts. These have been called ‘false pains’ but in fact they are part of the preparation for labour. Elizabeth Davis prefers to call them ‘practice contractions’ because otherwise women may feel that their body is deceiving them by being ‘false’. These early contractions differ from labour ‘pains’ only in that they are less regular and less effective in dilating the cervix.

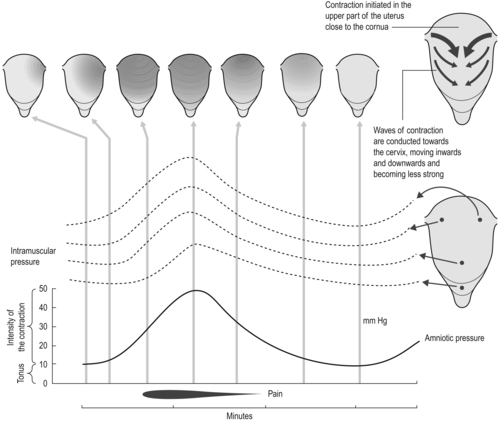

Myometrium contraction (Fig. 2.1)

The uterus is a smooth muscle and is mediated by the action of actin and myosin which is controlled by hormonal, biochemical, neurogenic and physical factors.

|

| Fig. 2.1 Contraction and retraction of uterine muscle cells. |

There is an intrinsic excitability of the uterine muscle which is dominated by hormonal influences during labour. This is due to the number and size of gap junctions. Gap junctions allow the transfer of current carrying ions and the exchange of second messengers between the cytoplasm of adjacent cells. Increased gap junction interaction will increase electrical impulses and therefore the contractility of the myometrium. Gap junctions are absent or infrequent in the non-pregnant myometrium and decline markedly within 24 hours of delivery.

The number and size of gap junctions increase to approximately 1000 per cell during labour (Benito-Leon & Aguilar-Galan 2001, Donaldson 1998, Garfield et al 1988). An increase in gap junctions has been reported in women with pre-term labour, and delay in formation is associated with prolonged pregnancy.

Neurological control of contractions is not critical due to this increase in gap junctions, which means that labour can occur in women with spinal injury. Contractions follow a cycle of activity of slow rhythmic fluctuation in the magnitude of electrical potential across the cell membrane.

What is physically happening is that the abdomen/uterus is tightening. A normal uterine contraction spreads downward from the cornus (top of the uterus) within about 15 seconds. The contractile phase begins slightly later in the lower portion of the uterus but functional coordination is such that the contraction’s peak is attained simultaneously in all portions during active labour. There is an increase in intrauterine pressure of approximately 10–12 mmHg which may increase to 30 mmHg with hypertonia (increased tightness of muscle tone). Contractions can be palpated abdominally with pressure greater than 10–20 mmHg and perceived by the woman at 15–20 mmHg.

A labouring woman generally perceives pain at pressure greater than 25 mmHg, although this varies. This means that the duration of a contraction assessed from palpation or a woman’s perception will be shorter than the actual contraction, and the duration between contractions will seem longer.

The uterus is divided into segments. The upper part of the uterus, known as the upper uterine segment (UUS), contracts strongly, and with each contraction the smooth muscle fibres become shorter and thicker. These muscles not only contract but ‘retract’. This means that when the active contraction passes the fibres re-lengthen, but not back to their former length. If they went back to their previous length, no progress would be made. Retraction means that some of the shortening of the muscle fibres is maintained and each successive contraction starts at the point where the previous one ended. With each contraction the uterine cavity becomes a little smaller. Retraction is a property of other muscles but is most marked in the uterus.

The powerful upper segment draws up the weaker, thinner and more passive lower segment and so the cervix dilates. During early pregnancy the lower segment is not clearly defined but by late pregnancy it is recognisable and corresponds with the lower limit of the firm peritoneal attachment to the uterus. Below this point the uterovesical peritoneum is loosely attached.

These two segments are not clearly formed until the end of the first stage of labour where they can be clearly seen. In labour, as the lower segment is drawn up, its shape changes from a hemisphere to a cylinder. If there is obstruction the restriction of the upper segment is even more pronounced.

In labour the lower uterine segment, cervix, vagina, pelvic floor and vulval outlet are dilated until there is one continuous birth canal. During the second stage the contractions of abdominal muscles and the diaphragm help the baby to be born.

Contractions are not continuous. This is extremely important for both the woman and the fetus. During a contraction blood circulation through the uterine wall is stopped: if the contraction were continuous the fetus would die of oxygen deprivation. The intervals between the contractions allow the placental circulation to be re-established. They also allow the woman time to recover both physically and emotionally from the contraction.

Ina May Gaskin describes the cervix as a sphincter along with the anus and vagina, and has theorised ‘the law of the sphincters’ (Gaskin 2003). She outlines the emotional factors which may contribute to the woman being able to relax and go with her contractions, rather than trying to resist, or block them out. If women are relaxed then dilatation happens. Gaskin also believes that women can go ‘backwards’ in dilatation if they are stressed and that dilation is not necessarily a forward linear process. Many doulas have noticed that if women visualise their cervix opening it can help it dilate. It must be recognised that there is no conscious control over the cervix, while there is over the anus and vagina. Physiologically, the vaginal ‘sphincter’ and anal sphincter are rich in muscle whereas the cervix hardly has any muscle and is mainly collagen. However, it may be that the emotions affect the cervix less directly through their effects on the neuroendocrine system.

Pain in labour

Even though labour is often experienced as painful and uncomfortable, there are some women who feel minimal discomfort, or who are able to use breathing, visualisations or other tools to positively perceive their contractions. Many birthing clients who have used bodywork to support them during labour report positive descriptions of contractions ranging from associating a positive experience of ‘pain’, to feelings of empowerment, or to finding labour an ‘amazing’ and even ‘enjoyable’ experience. There are recorded examples from women who have used hypnobirthing tools (Mongan method), or who refer to contractions as ‘rushes’ and even record feelings similar to orgasm (Gaskin 2002). More recently some women have referred to birth as ‘ecstatic’ (Buckley 2005) or ‘beautiful’ (Yates 2008). Grantly Dick-Reid (1984) was one of the first obstetricians to record his surprise at a woman in labour who did not feel pain but often the possibility of experiencing contractions in this constructive fashion may be met with scepticism by those who assume labour must be a painful experience.

The perception of pain is influenced by physiological, psychological and cultural factors. Anxiety will influence the course of labour, reducing pain toleration. Relaxation seems to play an important role in breaking this cycle (Jimenez 1983). Many writers attribute the naturally released hormones which are produced during labour as being to a large part responsible for experiencing birth in a positive way (Buckley 2005).

Discomfort or pain is experienced as either visceral (due to the contractions of the uterus and how this affects both the uterus and other organs and tissues of the body), or it can be somatic (due to the pressure of the fetus on the cervix and surrounding structures).

Visceral pain

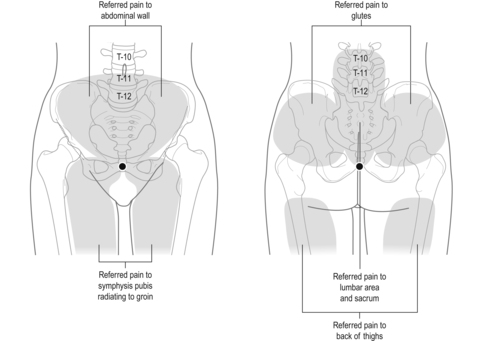

Visceral pain is related to the contractions of the uterus and the dilatation of the cervix. Pain caused by the contraction of the uterus is transmitted by afferent fibres to the sympathetic chain of the posterior spinal cord at T10–T12 and L1. In early labour and during transition this is mostly between T10 and T11. Pain can be referred and may be experienced over the abdominal wall, between the umbilicus and symphysis pubis, around the iliac crest to the gluteal area, radiating down the thighs, and in the lumbar and sacral regions (Smith et al 2000; Fig. 2.2).

|

| Fig. 2.2 Pain sites in labour. |

During second stage, pain is transmitted more through the posterior roots at S2, S3 and S4 and therefore may be experienced lower down, so is likely to be somatic pain.

Pain caused by the dilation of the cervix is usually stronger towards the end of first stage. Sensory impulses from the cervix probably enter the cord via the sacral roots. Pain at the end of the first stage is often referred to the sacral region.

Somatic pain

This is caused by pressure of the presenting part of the fetus on the cervix. It is more likely to be experienced during the second stage of labour.

Gate control theory

This theory postulates that the nervous stimuli can be inhibited at the level of the substantia gelatinosa and the dorsal horn of the spinal cord from reaching the thalamus and cerebral cortex (Melzack & Wall 1983).

The gate control theory is used as a basis for promoting the use of massage and strokes such as effleurage during labour. These modalities are considered to be a distraction from the pain messages that the brain is processing. The gate control theory has also been considered in the development of TENS machines for pain relief.

In simple terms there are thought to be ‘gates’ at the spinal cord. If these gates can be ‘closed’, then whatever pain stimulus arrives at the level of the spinal cord will not be allowed up the cord to the brain and therefore will not be experienced by the woman as pain.

(Dr J Barrett)

2.2. Stages of labour

Labour has traditionally been divided into three different stages, although the stages are not always clearly defined for the birthing woman. They may seem to flow into one another. Some writers have recently suggested that for this reason, it may be more useful to consider labour as a continuum from onset to completion, characterised by particular physiological and psychological behaviours at various points (Downe 2000).

This social model places an emphasis on the differences between individual women’s experiences, and underscores the importance of trusting a woman’s physiology to function optimally. This approach may have a positive impact on the woman’s view of her labour, and tends away from imposing set time frames for different stages of labour (Gould 2000, Green et al 1998).

It is important to recognise that there can be differences between nulliparae and multiparae labours. There can also be differences in labours between women of different cultures and races. For example midwives have observed that, probably due to differences in the pelvis, with Afro-Caribbean women the fetus does not tend to engage before labour begins.

The following information relates to what happens in ‘unmedicated’ labours. In this section, as we consider what supports or impedes the process of labours, we are primarily considering treatment strategies which are within the bodyworker’s scope of practice, including self-help activities for the client. It is important to differentiate this from the care given by the primary care provider. Their scope of practice may include similar tasks to bodyworkers such as providing supportive and encouraging words and behaviour towards their client, but also has the primary task of safe care of the woman and her baby. It therefore also includes medical interventions which are discussed under the medical approach to labour.

Latent and first stage labour

What is happening?

• Contractions serve to thin/efface the cervix from 0 to 100% and to dilate/open the cervix from 0 cm to 10 cm, which is considered full dilatation.

• Latent labour is the phase of labour which takes the longest amount of time and can vary most in its duration. For a nulliparae it may take several days but multiparae may skip the latent phase. Generally, this phase tends to be shorter for multiparae.

• Once the active phase begins then the cervix usually dilates at around 1 cm/h or more from 3 to 10 cm.

• Transition ends the first stage of labour with the cervix dilating from 7 (8) to 10 cm.

One of the most common questions for families to ask during the latter stages of their pregnancy is how to determine whether the woman is in labour or not. This may be challenging for a woman who has never experienced labour before.

Latent first stage labour

This is before labour is ‘established’. It can last for days with irregular contractions, or may even pass unnoticed. It is sometimes known as the ‘stop/start’ phase of labour. The contractions do not get progressively stronger and closer together and can be sporadic in nature. There can be an hour or two of strong, close together contractions, which may even be quite painful, but then they stop. These contractions usually last about 30–40 seconds each, and vary from 3 to 20 minutes apart. What is happening is the uterus is contracting but the contractions are not co-ordinated. Some practitioners refer to them as ‘warm up’ contractions. Sometimes, if the fetus is not in the best position for birth, the contractions of the uterus help to better position the baby rather than dilating the cervix.

Active first stage labour

This is the ‘established’ phase and usually lasts around 10–12 hours in a nullipara, but can be as little as1 hour or as much, or more, than 36 hours. The contractions get closer together and stronger and last longer than in the latent stage. Contractions can last for 40 seconds and are 3–4 minutes apart. They have a more regular pattern of interval and duration, and are progressively building in length and intensity. Eventually they can last for up to 1 minute or more and come every 1.5–3 minutes. After about 6 cm they tend to get closer together and therefore seem more painful and longer as there is not as much time to rest in between. The woman will feel her abdomen hardening, as she may have in latent first stage; this is the uterus contracting. This will happen with more rhythm and strength as first stage progresses. As the baby’s head is pushed deeper into the pelvis it flexes. The pressure of the head stimulates the cervix and perineum which in turn brings about stronger contractions. Although there is pressure from the presenting part there may not necessarily be much actual descent of the baby.

What can impede progress in the first stage of labour

The birthing environment, both ‘within and without’

• Fear and anxiety.

• A location that is noisy, cold, overly bright, or busy.

• Mental activity, e.g. too much ‘expectation’.

• Inertia – sometimes physical activity, such as a long walk, may help get labour established.

If these circumstances cause anxiety in the woman, there may be an increase in the release of adrenaline. This can inhibit the production of oxytocin and endorphins with a result that physiologically labour may become more painful. The release of adrenaline occurs as part of the ‘fight or flight‘ mechanism. It has been observed that if an animal is under threat in labour, she may either give birth quickly (if she has progressed sufficiently along in her labour, i.e. late second stage) or the birthing process will actually cease until she finds a safe place.

The same is probably applicable to humans as stress and interruptions affect the birthing process. An example of this is shifting the location of labour from home to hospital. Regardless of whether women prefer to birth at home or in the hospital, ensuring the woman is in her preferred space in a timely and smooth fashion is important. A major concern related to choice of birthing location is safety, and this means different things to every woman and family. Some women prefer to be in a hospital setting, with medical staff and equipment close at hand. They, or their partners, would feel too anxious delivering within their home situation. However, many women look forward to a home birth because they find the hospital setting to be less familiar and even frightening. The comfort of being in their own home helps them cope better with labour.

Creating ‘safe and comforting strategies’ which help the woman attune to a more relaxed state is an important process in either environment.

Being stationary or immobilised

Ineffective positioning and immobility may make labour more prolonged and/or painful because there is less mobilisation of the pelvis and use of gravity which tend to encourage descent of the fetus. Lying down and static positioning are relatively new events in the birthing process, and may have an effect on the increased use of interventions to deliver babies. Prolonged or static positioning may also increase musculoskeletal discomforts such as low back pain.

Physical activities such as walking, swaying and remaining upright can literally help ‘mobilise’ the birthing process.

Exhaustion

Some women misinterpret the idea of ‘active’ birth to mean they have to be active and in motion from the moment they have their first contraction. If they have a long labour, this could result in exhaustion. It is important to rest and relax as much as possible, especially between contractions. Holding unnecessary physical tension may also tire the woman. Listening to one’s body, staying calm and relaxed, being efficient in terms of energy output and type of physical activity, as well as staying as comfortable as possible is crucial. Exhaustion may slow labour down: as the woman gets tired, so may her uterus, and this can lead to a sense of discouragement and defeat.

Lack of nourishment

Labour can last many hours, and it is not appropriate to deprive a woman of nourishment. It is estimated that labour requires a similar caloric intake to someone engaged in strenuous sport. If there are no carbohydrates available for conversion to glycogen, body fat will be utilised and so the quantity of ketones in the tissue and blood may increase (Foulkes & Dumoulin 1983).

It is important for the woman to eat what she feels like eating, when she feels like it.

For a normal labour, and if the woman is able, it is recommended that she eat frequent, light meals which are low in fat and roughage and easy to digest. Fluids should also be taken to prevent dehydration (Ludka & Roberts 1993, Sharp 1997).

Instinctively, many women have no appetite for heavy meals that take energy and time to digest. Many care providers will leave food choices up to the woman. Some hospitals have policies restricting food intake in the event that the need arises for a general anaesthetic. However, fasting in labour does not ensure an empty stomach and anaesthetic techniques have improved so that aspiration of gastric contents is unlikely (Baker 1996, Johnson et al 1989, Tranmer et al 2005).

Self-doubt and/or giving up

Some women can be managing well in labour when a misplaced word or two from someone around them creates self-doubt about their progress. Everyone involved in the labour process, from care providers, to doula, to partner, needs to be aware of the words they use, their facial expressions, their body language and their attitudes. It is amazing how quickly women can shift from being positive, focused and coping well to feeling overwhelmed and ready to give up! This can occur with a vaginal examination when the woman finds out her cervix is not as dilated as she had hoped. Encouragement from the partner and care providers is vital in helping the labouring woman stay focused and well supported.

Full bladder

Along with feeling uncomfortable, ‘bladder distension can result in uterine atony and affect its ability to contract’ (Bobak & Jensen 1993: 507). The woman needs to empty her bladder at least every hour or two. This also helps to keep her mobilised. If the woman is unable to urinate, she may need to be catheterised.

What supports first stage labour

This is explored in practical labour (refer Ch. 10, section 10.4 p. 297.

Transition

What is happening?

This indicates the end of the first stage of labour with the body beginning to get ready for second stage. The cervix is completing its final stages of dilation (8–10 cm).

In this phase, contractions will be closer together, as frequent as every 2 minutes, and they will also be longer, lasting up to 60 seconds. Things are physically getting more intense. The woman may feel hot and cold, vomit or feel nauseous, have shaky legs, grunt, feel pressure in her anus or empty her bowels. Emotionally it can also be intense. The woman may feel angry, frustrated, or feel that she cannot go on. It is the point in labour when she may berate her partner, or ask for an epidural or caesarean, even though she may have been doing fine with no desire for interventions prior to this phase. She may feel very tired and need to rest. In fact, labour may appear to have stopped. Transition may be brief, a few minutes, or it may last up to an hour or more. The important thing for both woman and partner to remember is that all of this intensity is an indicator that her body is getting on with labour, the cervix is dilating, her body is preparing to give birth. It means things are moving along. If these can be seen as ‘good’ signs and accepted, it is easier to cope. ‘Oh, this is that intense phase of labour!’

The woman may feel an urge to push because of the increased pressure of the baby’s head low in the pelvis, but this can sometimes happen before the cervix is completely dilated. If so, it is usually best for the woman to try not to actively push, but to relax and breathe during the contractions to feel what her body is doing. Telling a woman not to push may be counter-productive because she may then feel confused about what her body wants her to do. Pant breathing, which is often advocated, may make the woman disconnect from her own breathing rhythm and may not be particularly effective in reducing the urge to bear down. It is often preferable to give the woman strategies such as encouraging her to shift into positions such as the knee to chest position, where her pelvis is higher than her head in order to reduce pressure on the cervix.

Sometimes when the cervix is fully dilated there can be a pause in the intensity of the labour. Some women may feel drowsy or like going to sleep, especially if it has been a long first stage. It is important to wait until the woman feels strong second stage contractions before bearing down because the baby may still need to adjust its position and bearing down may force it into the wrong position. Some midwives call it the ‘rest and be thankful’ stage. It makes sense for the body to have a little rest before going into the potentially more physically demanding second stage.

Some women become vigilant and awake (even chatty) which is a sign of an increase in catecholamines. Odent suggests a surge in catecholamines causes the ‘fetal ejection reflex’ (Odent 1992).

What can impede transition

• Exhaustion.

• Feeling unheard and/or unsupported.

• Being in an uncomfortable position.

• Lying supine.

• Feeling frightened.

• Feeling cold or overheated.

• Giving up.

Second stage labour

What is happening?

The contractions are called expulsive contractions as they are now working to push the fetus down the birth canal and out into the world.

It is usually best for the woman to try to be patient and wait, and not to bear down actively until the desire to push is overwhelmingly strong. It is important to let the body take over and for the woman to be able to go naturally with what she feels. Some women do not need to bear down strongly and the baby comes out gently. Some women have strong physical contractions. Some babies are born within one or two contractions, others take their time. Like all phases of labour this can be very different for everyone. Pushing should not be about forcing the baby out, but letting the woman’s body give birth. The woman may start to try to push because she thinks that is what should happen next rather than what her body is actually needing to do. It is important to encourage the woman to listen to the sensations of her body and work with what needs to happen. Studies have shown that women tend to do more effective bearing down when they are responding to their body rather than being told to push (Enkin et al 2000).

The ligaments provide stretch for the bones of the pelvis to move in order to allow this process to happen. This stretch helps give enough space for the delivery of the baby. The coccyx moves slightly out of the way. It is important to know that the bones of the spine and the pelvis move; they are not fixed. The more the woman can understand, envision, and allow this process of opening and stretching to happen, the easier the delivery can be.

With each contraction the presenting part of the baby is forced down on to the pelvic floor, facilitated by the action of the abdominal wall and the diaphragm. In between contractions, the pelvic floor can push the presenting part back up again. This is where uterine retraction is important, as progress is not completely lost. Eventually the presenting part is stationary at the end of the contraction. The baby’s head gradually comes down. With a nullipara, the baby’s head may become visible at the perineum before it exits.

When the widest diameter of the head appears this is what is known as ‘crowning’. For a first time delivery this can be painful as the perineum stretches, and is sometimes described as a burning sensation. Perineal massage or hot compresses may support the process of stretching, while also providing some comfort.

In the second stage there is some moulding of the baby’s head. The sutures of the baby’s skull are not fused which allows movement of the bones to ensure the baby’s head is sized in conjunction with the mother’s pelvis.

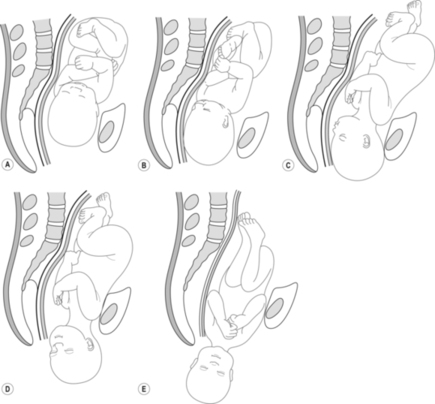

There are four movements of the baby’s head in this stage (Fig. 2.3): (i) internal rotation; (ii) extension; (iii) restitution; (iv) external rotation.

• Internal rotation: when the head meets the resistance of the pelvic floor the occiput rotates forward from the left occiput transverse (LOT) or left occiput anterior (LOA) position to lie under the subpubic arch.

• Extension: as the head advances it passes through the vulva by a process of extension. This causes the anterior part to stretch the perineum gradually until the moment of crowning when the greatest diameter slips through the vulva.

• Restitution: as the head descends the shoulders enter the pelvic brim. When the head has internally rotated it is twisted a little on the shoulder. Once it is born it resumes it natural position and this is called restitution.

• External rotation: as the shoulders descend one shoulder meets the resistance of the pelvic floor first and rotates to the front, and the head also rotates as the shoulders rotate.

|

| Fig. 2.3A–E The various movements the baby makes during the journey of second stage: descent, internal rotation, extension, restitution, external rotation. |

Some maternity care providers help to control the exit of the baby’s head as well as allowing for slow stretch of the perineum by providing direct hands-on contact with the perineum. This may include the application of pressure to the area, or perineal massage to help facilitate the stretch of the tissues and minimise tearing. Other maternity care providers rely on the efforts of the woman’s pushing without any touch contact, allowing the head to be delivered and the perineum to stretch and adapt to the forces of the delivery.

It is helpful if the woman is in tune with bearing down and does not overpush at the moment of crowning because otherwise the perineum can tear and the baby may be born too rapidly.

When the head is born, the maternity care provider slips their fingers over the occiput to see if the cord is around the neck. If so, it must be freed, or a loop made large enough for the shoulders to pass through. The birth of the trunk should not be hurried and usually comes out with another contraction. Following restitution and external rotation of the head, the shoulders should be in the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis. Then they can be delivered safely without the risk of perineal trauma.

This stage is shorter than first stage and actively bearing down would tend not to be more than 2 hours for a nulliparae, and for multiparae may be 15 minutes or less. The end of first stage does not, however, necessarily mean the beginning of second stage. It is important that second stage is measured from the actual start of it, i.e. when the woman experiences the urge to bear down, as otherwise unnecessary time limits may be imposed on the woman.

Sometimes women can be fully dilated but they do not have an urge to push and so there is a period of waiting between the phases.

What can impede the progress of second stage

If a woman does not feel a spontaneous urge to push, is unsure of ‘how to push’ or whether she is ‘doing it correctly’, feels rushed or forced to push, or has any fear related to the final exit of the baby from her perineal area, she may become anxious and tense, or panic. This can result in unproductive attempts to bear down. Further unproductive efforts may occur if there is tension in the upper body, particularly in the neck and shoulder regions, or if the woman is holding back from bearing down into her pelvis and perineum. Straining can be tiring and the woman may find that she runs out of energy.

Lying semi-supine may result in unproductive pushing and other positions such as upright forward leaning, standing or assisted semi-squatting can be encouraged. However, the most important factor is that the woman is as comfortable as possible.

A full bladder can also interfere with second stage by affecting the uterus and its contractility.

Third stage labour

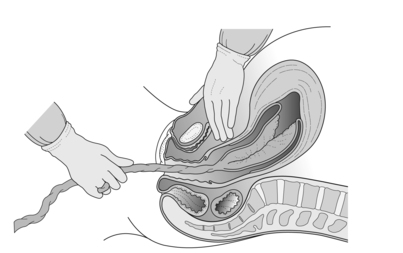

What is happening? (Fig. 2.4)

|

| Fig. 2.4 Placental separation. |

This stage is the delivery of the placenta. If this stage proceeds without intervention (physiological third stage) then it takes about 15 minutes but may take up to 1 hour or longer (Prendiville & Elbourne 1988).

The third stage is similar to second stage, but usually not as intense. Uterine contractions continue so that the placenta is sheared off the wall of the uterus. The placenta is smaller than the baby with no bony structure so it is easier to deliver through the passage already created by the baby. The placenta may be delivered with one contraction. Separation of the placenta usually begins with the contraction which delivers the baby’s trunk and is completed within the next two contractions. Most women feel a difference with these contractions. As there is no longer a head pushing on the pelvic floor, they may feel the contractions as less urgent and intense. Some women, however, are surprised at the strength of contractions with this part of the delivery, particularly if they presumed they would not experience intense pain after the baby has been born.

As the baby is delivered there is a marked reduction in the size of the uterus due to the powerful contraction and retraction which takes place. The placental site reduces substantially in size. When the placental site is reduced by about one half, the placenta, being inelastic, becomes wrinkled and then is shorn off the uterine wall. It is tightly compressed by the contracted uterus. Some fetal blood is pumped back into the fetus’s circulation and maternal blood in the intervillous spaces is forced back into the veins in the deep spongy layer of the decidua basalis. The blood in these veins cannot return to the maternal circulation because of the contracted and retracted state of the myometrium. The result is that the congested veins rupture and this small amount of extravasated blood is sheared off the villi from the spongy layer of the decidua basalis thereby separating the placenta from the uterine wall.

Bleeding is controlled by the action of the interlacing spiral fibres, named ‘living ligatures’, which contract around the torn maternal vessels to prevent further blood loss. This process happens rapidly. Brandt (1993) studied 30 women in third stage and found that in all cases the placenta had completely separated from the uterine wall within 3 minutes of delivery and was lying in the lower uterine segment.

When separation is complete the upper uterine segment contracts strongly forcing the placenta into the lower segment and then into the vagina. Detachment of the membranes begins in the first stage of labour and is completed in the third stage assisted by the weight of the descending placenta which peels them from the uterine wall.

After separation, bleeding from the placental site is controlled by:

1. The powerful contraction and retraction of the uterus.

2. Pressure exerted on the placental site by the walls of the uterus.

3. The blood clots at the placental site.

This stage is potentially dangerous because if the blood vessels which attached the placenta to the wall of the uterus do not close up, then there is a risk of haemorrhage. The woman’s body is designed to deliver the placenta as well as the baby, and in a labour which has progressed without complication, and with a woman who has no history of haemorrhage in previous deliveries, there would be less likelihood of an indication for administration of drugs such as oxytocin.

In order to support a physiological third stage, the cord is not clamped immediately and is allowed to stop pulsating because the baby gets about 50 ml of blood from the placenta as the lungs expand with the first breath. It is best to keep the baby at the same level as the placenta or a little lower. If the baby is held high above the placenta (which may be inadvertently done in caesarean section) blood may run back into the placenta with the risk of hypovolaemia or subsequent anaemia in the fetus. It is also thought holding it lower may reduce the risk of haemorrhage for the mother (Yao & Lind 1969).

During the third stage of labour, supportive care is still essential. Creating an atmosphere of calmness and attention to the woman and her baby are essential. At this time, the high noradrenaline levels of the second stage, which may have kept woman and her baby wide-eyed and alert at first contact, will be decreasing. A warm and comforting atmosphere can counteract the cold, shivering feelings that a woman may have as her noradrenaline levels drop. If the environment is not well heated, and/or the woman is worried or distracted, continuing high levels of noradrenaline will counteract oxytocin’s beneficial effects on her uterus. This, according to Michel Odent (1992), may increase the risk of haemorrhage.

Delivery of placenta with twins

Usually, even if there are two placentas they are both delivered after both twins have been born. If there is one placenta it is delivered after both babies have been born.

What can impede third stage

• Not promoting skin-to-skin contact whereby the baby can nuzzle at the mother’s breast or latch when possible (thereby increasing the release of oxytocin hormones to help the uterus contract).

• Not emptying the bladder.

• Exhaustion.

• Giving up.

• Feeling cold.

• Worry – for example if the baby is taken away from the woman and she cannot see the baby or does not know what is happening.

Fourth stage

Immediately post birth

The fourth stage is essentially the rest of the woman’s, the newborn’s and the family’s life. However, in the immediate period after birth it is important to give space for the initial bonding to happen between the woman and her baby, and for skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding to begin.

The maternity care provider will check that the placenta is intact and therefore has completely separated, and that vaginal blood loss is within normal limits. If any of the placenta remains inside the uterus, it may cause excessive blood loss and/or infection. The perineum will be checked for tearing and suturing will be carried out if necessary.

What can impede the process of fourth stage

• If the woman has had drugs during the birthing process, particularly narcotics which may block the process (Bridges & Grimm 1982, Kinsley et al 1995, Stafisso-Sandoz et al 1998).

• Having the baby taken away unnecessarily.

This is the time for the support people to stand back and allow the woman and the baby’s father/partner or other family members to be with their baby in a nurturing environment.

What supports fourth stage

Relaxation, reassurance, bonding time, providing a space to be together as a family (see postnatal practical, p. 313).

• Knowledge:

It is important to have a sound knowledge of what is happening physiologically as well as emotionally during the different stages of labour.

• Supportive comfort measures:

An understanding of what supports or may impede the progression of each stage in order to provide relevant and encouraging care for the woman and her family.

• The role of emotions and stress:

Understanding the role emotions play during all aspects of the birthing process, and the importance of reducing stress are fundamental elements of the bodyworker’s supportive care.

Studies on doula care have indicated that comfort measures on a physical and emotional level can positively affect the outcome of labour. Stress has been shown to be a factor in women’s perception of their ability to cope during labour and its relationship to birth outcome (Hodnett 2002).

• Environment:

The bodyworker needs to help create and maintain a calm space in the time before labour as well as during labour itself. Most women do need some form of emotional encouragement during labour.

• Pain relief in labour:

There is usually some degree of discomfort for the birthing woman. The following areas of the body are key areas to apply treatment modalities, whether massage, shiatsu, reflexology, etc.: T10–L1, the abdomen, especially between the umbilicus and pubic bone, the iliac crest to the gluteals and greater trochanter region, the lumbar and sacral areas, and the thighs.

2.3. Fetal position/presentation

This section examines the positions and growth of the fetus, fetal presentation, descent of the fetus and movement of the fetus during the birth process.

The ‘position’, ‘presentation’ and ‘lie’ of the fetus at the start of labour will influence the outcome of labour. The position of the fetus as well as the position of the birthing woman are key factors in the progression of labour.

Lie

The ‘lie’ means the relation which the long axis of the fetus bears to the uterus. It may be longitudinal, oblique or transverse.

Presentation

The ‘presentation’ refers to which part of the head or body is in or over the pelvic brim. When the head is first it is called ‘cephalic’ and if the head is flexed on the spine then the vertex presents. If the head is fully extended on the spine there is a face presentation, and if partly extended, a brow presentation. If the bottom presents first then it is called a ‘breech’ presentation.

If the fetus lies obliquely then the shoulder lies over the cervix and this is called a shoulder presentation. Any presentation other than vertex is referred to as a ‘malpresentation’.

Position

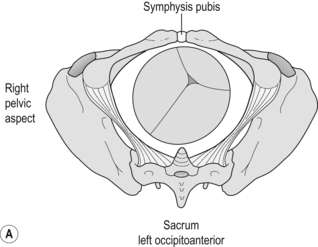

The ‘position’ describes the relationship which a selected part of the fetus (the denominator) is in, in relation to the maternal pelvis. With a vertex presentation the denominator is the occiput. There are six presentations (Fig. 2.5):

• Left or right occiput anterior (LOA or ROA). Anterior means to the anterior of the woman’s body, i.e. the back of the baby’s head (occiput) and its spine are presenting at the front of the woman’s body.

• LOP and ROP (left and right occiput posterior) are the opposite, i.e. the back of the baby’s head (occiput) and spine are facing the direction of the woman’s spine.

• LOT and ROT (left and right occiput transverse) mean the occiput lies in the transverse diameter of the pelvic brim.

|

|

| Fig. 2.5 A and B Different presentations; anterior and posterior. |

The fetus makes various movements, twists and turns on its journey down the birth canal, and it is generally accepted (e.g. Henderson & Macdonald 2004, Lewis & Chamberlain 1990) that the position of the fetus which most supports this process is anterior cephalic.

The position of the first twin is an important consideration if a woman is having twins. The second twin is usually smaller and therefore it is easier to pass through the space already created by the first and larger fetus.

It is important to remember that as the fetus changes position during labour it may subtly move out of position, either due to the shape of the woman’s pelvis or due to the position the woman is in. This can result in the use of interventions in the labour. Labour may slow down or be more painful for the woman if the fetus is stuck within the pelvis or not progressing down the birth canal.

Fetal position can be affected by other factors as well, such as: the shape of the woman’s pelvis, the shape of the uterus, especially with uterine abnormalities, any blockages in the uterus such as fibroids or cysts, the tone of the abdomen, the size of the fetus, the position of the placenta, or issues related to the umbilical cord. Fetal position is also thought to be affected by the position of the woman both leading up to labour and during labour itself.

Traditionally the maternity care provider would assess fetal position from 28 weeks onwards. The UK NICE guidelines recommend assessment only after 36 weeks as prior to this the fetus can change position frequently. However, the fetus usually goes into spontaneous version between 30 and 34 weeks. While it is true that the fetus can change position right up to, and in, labour, and it is difficult to be sure of the position until 34–36 weeks, this aspect of antenatal care is often appreciated by the woman because it may help her to focus on her baby within. Many practitioners include assessing position as a way of supporting the woman’s connection with her baby. It may also encourage the woman to be motivated in terms of practising forward leaning positions, which will not only help strengthen her body, but can also help prepare her for utilising upright birthing positions. From 34 to 36 weeks it is relatively easy to feel if a fetus is posterior or anterior, but harder to assess breech or cephalic. Even the maternity care provider may find it difficult to assess breech through palpation alone at this stage and if there is concern, ultrasound may be required to establish an accurate assessment.

Use of ultrasound for assessment of fetal position and fetal growth

In the third trimester ultrasound may be used for verifying fetal presentation if there is concern, for example in cases of suspected breech. It may also be used for rechecking the position of the placenta if it had been assessed as low lying during the second trimester scan, or if there is vaginal bleeding.

Engagement of presenting part

The other aspect assessed is fetal engagement. If the fetus is cephalic the assessment is how much the fetal head has engaged in the pelvic inlet (i.e. below the level of the pubic bone). This is measured in fifths, with a measurement of  meaning that

meaning that  of the fetal head is palpable above the pubic bone and only

of the fetal head is palpable above the pubic bone and only  has engaged;

has engaged;  is therefore more engaged than

is therefore more engaged than  and

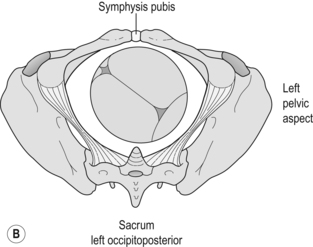

and  is fully engaged. In some countries engagement is assessed according to ‘station’ which is determined by vaginal examination (Fig. 2.6). This relates the head of the baby relative to the ischial spines of the woman’s pelvis. This is assessed as −1, −2 and so on, i.e. how much the head is presenting below the level of the ischial spines. This is also used in labour itself to determine the further descent of the head which occurs during labour.

is fully engaged. In some countries engagement is assessed according to ‘station’ which is determined by vaginal examination (Fig. 2.6). This relates the head of the baby relative to the ischial spines of the woman’s pelvis. This is assessed as −1, −2 and so on, i.e. how much the head is presenting below the level of the ischial spines. This is also used in labour itself to determine the further descent of the head which occurs during labour.

meaning that

meaning that  of the fetal head is palpable above the pubic bone and only

of the fetal head is palpable above the pubic bone and only  has engaged;

has engaged;  is therefore more engaged than

is therefore more engaged than  and

and  is fully engaged. In some countries engagement is assessed according to ‘station’ which is determined by vaginal examination (Fig. 2.6). This relates the head of the baby relative to the ischial spines of the woman’s pelvis. This is assessed as −1, −2 and so on, i.e. how much the head is presenting below the level of the ischial spines. This is also used in labour itself to determine the further descent of the head which occurs during labour.

is fully engaged. In some countries engagement is assessed according to ‘station’ which is determined by vaginal examination (Fig. 2.6). This relates the head of the baby relative to the ischial spines of the woman’s pelvis. This is assessed as −1, −2 and so on, i.e. how much the head is presenting below the level of the ischial spines. This is also used in labour itself to determine the further descent of the head which occurs during labour. |

| Fig. 2.6 Stations of the head. |

If the fetus is breech then the ‘presenting part’ is the buttocks, knees or feet.

The fetus tends to engage earlier in a primipara as opposed to multipara, probably due to the role of tighter abdominal muscles pushing the fetus down. It is also common for babies of Afro-Caribbean women to not engage before birth due to the differing shape of their pelvis (midwives’ clinical observations and Homebirth.org). If the fetus is not engaged with a primapara in the weeks leading to term it may be possible that there is an issue such as cephalopelvic disproportion, low umbilical cord, low lying placenta, or poor fetal positioning such as posterior or transverse, although the last is rare.

During labour itself, the head descends further down into the pelvis and from the level of the ischial spines it is measured as −1, −2 and so on above or below the spines.

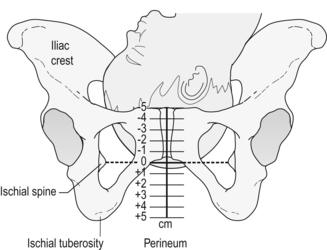

At the onset of labour many fetal heads are asyn-clitic (Fig. 2.7). This means that the head is angled so that one parietal bone enters the pelvis first and the fetal biparietal diameter is not parallel to the plane of the inlet of the pelvis. As labour progresses and the head descends deeper into the pelvis it usually assumes the synclitic position.

|

| Fig. 2.7 Asynclitic head position. |

If the baby’s head remains asynclitic, progress of labour can be slowed. In some cases the head becomes arrested with its long axis in the transverse diameter of the pelvis, the degree of extension being such that neither the occiput nor the forehead is sufficiently advanced enough to influence rotation. This is called ‘deep transverse arrest’.

Positions of the baby and how these affect labour

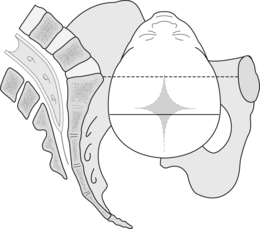

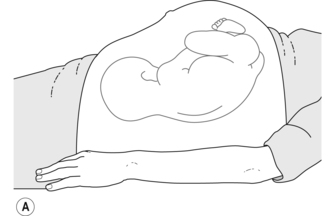

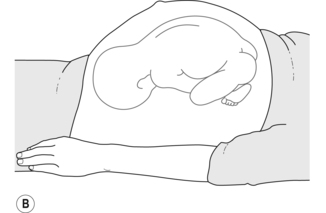

SeeFigure 2.8.

|

|

| Fig. 2.8 Shape of woman’s abdomen near full term pregnancy, OA (A) and OP (B). |

Anterior cephalic position

This is the ‘ideal’ position which most supports the normal process of labour. The head of the fetus is down, with its spine (and head) away from the woman’s spine. The fetus is more often in the LOA position (left occiput anterior), probably due to anatomy (the woman’s spleen and stomach are softer than her liver and gallbladder) and the shape of the pelvis. ROA (right occiput anterior) is less common (Henderson & Macdonald 2004).

An anterior position is not only more comfortable for the woman prenatally and in labour, as there is less pressure on her sacrum, but it also facilitates the descent of the head through the pelvis. The pelvic inlet is widest horizontally (side to side), the outlet widest vertically (top to bottom). The baby’s head in an anterior position tends to be more flexed and stimulates the cervix more. It will therefore pass more easily through the birth canal. The cardinal movements of fetal descent are described in the section on the second stage of labour (i.e. internal rotation, extension, restitution, external rotation) (Lewis & Chamberlain 1990).

Posterior presentation

The occiput posterior (OP) position is the opposite presentation to occiput anterior (OA). In this position, the back of the baby’s head (occiput) and spine lie against the woman’s spine and sacrum. Right occiput posterior (ROP) tends to be more common than left occiput posterior (LOP). It is the most common malposition of the fetus with a vertex presentation. It occurs in about 10–25% of pregnancies during the early stage of labour and in 10–15% during the active phase (Cunningham et al 1997).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree