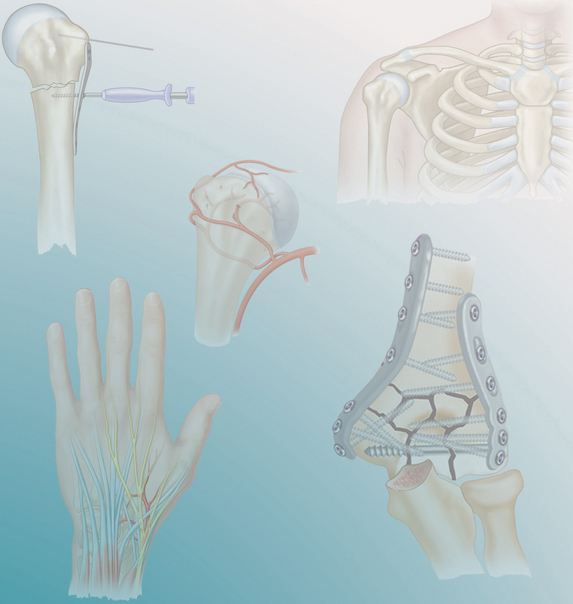

Indications

• Prioritize commonly associated life-threatening injuries: head, spine/spinal cord, chest, brachial plexus, vascular

• Anterior rim fractures may be treated nonoperatively if the glenohumeral joint remains concentric.

Specific indications: relative to the portion of the glenoid involved

Specific indications: relative to the portion of the glenoid involved• Glenoid neck fractures (extra-articular fractures)

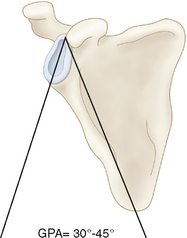

♦ Significant angulation: transverse or coronal plane greater than 20–40° or glenopolar angle (GPA) less than 20° (normal, 30–45°) (Romero et al., 2001). The GPA is measured on an anteroposterior radiograph as the angle between the line connecting the most cranial with the most caudal point of the glenoid cavity and the line connecting the most cranial point of the glenoid cavity with the most caudal point of the scapular body (the lateral boder of the scapula) (Fig. 1).

Examination/Imaging

PLAIN RADIOGRAPHY

Shoulder trauma series

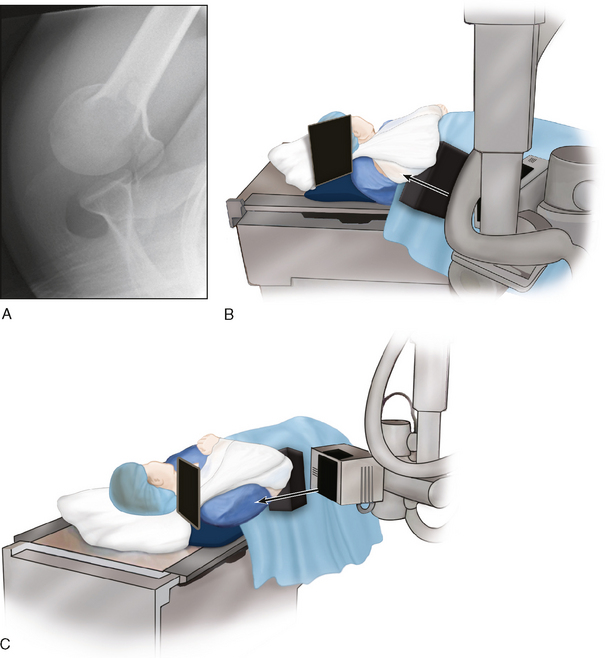

Shoulder trauma series• Obtain anteroposterior (x-ray beam tangential to glenoid/perpendicular to the plane of the scapular body), trans-scapular lateral, and transaxillary views.

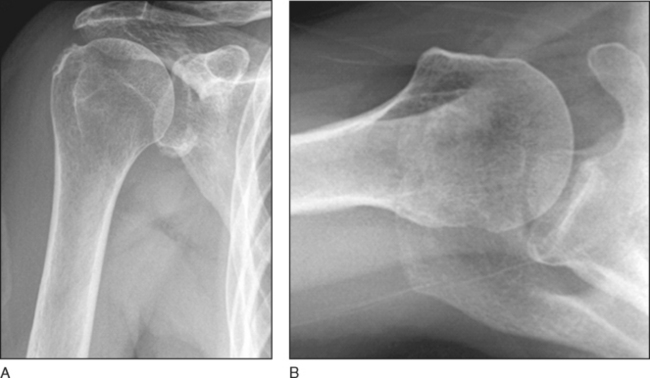

Assess scapula-glenoid fractures and detect associated shoulder girdle injuries: clavicle; proximal humerus; disruptions of the acromioclavicular, glenohumeral, sternoclavicular, and scapulothoracic articulations; suspensory ligamentous complex injury.

Assess scapula-glenoid fractures and detect associated shoulder girdle injuries: clavicle; proximal humerus; disruptions of the acromioclavicular, glenohumeral, sternoclavicular, and scapulothoracic articulations; suspensory ligamentous complex injury. It is important to differentiate true fossa fractures from anterior and posterior rim fractures.

It is important to differentiate true fossa fractures from anterior and posterior rim fractures.• Anterior and posterior rim fractures (type I; see Surgical Anatomy) are larger than Bankart “bony avulsions,” which occur when the humeral head loses its congruity as it dislocates anterior to the glenoid. Rim fractures result from a relatively eccentric lateral force that drives the humeral head against the anterior or posterior portion of the glenoid fossa depending on arm position.

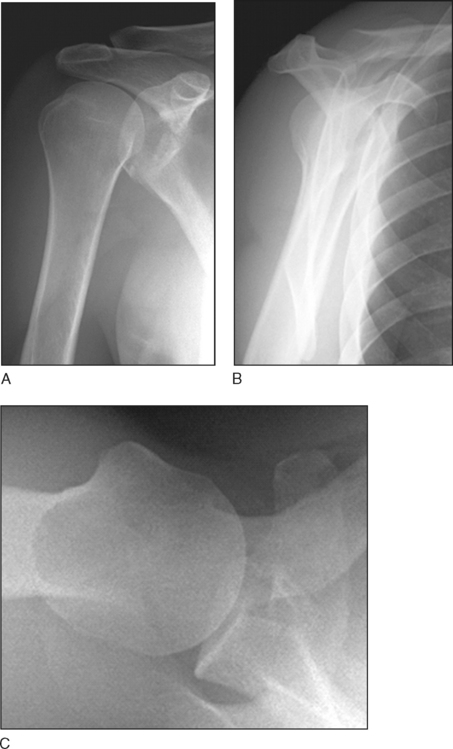

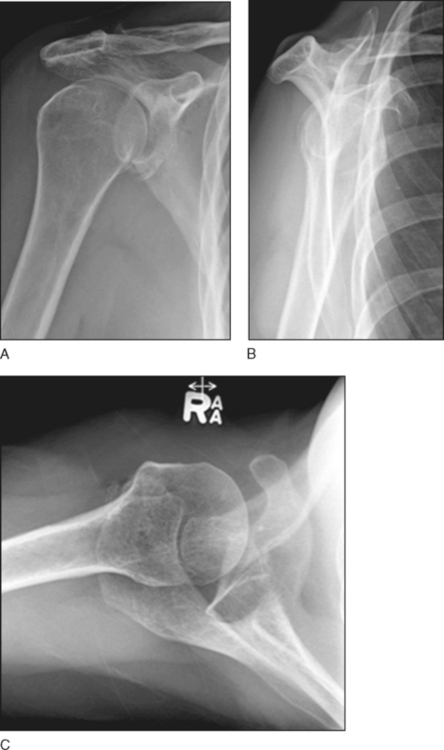

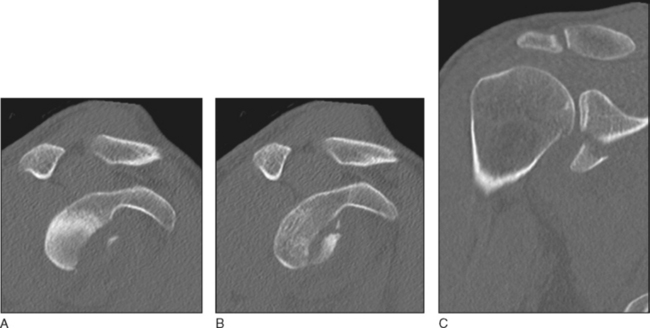

♦ Figure 3A–C shows an anterior rim fracture with maintained concentric glenohumeral alignment in a 63-year-old female accountant who was treated nonoperatively (Case 1).

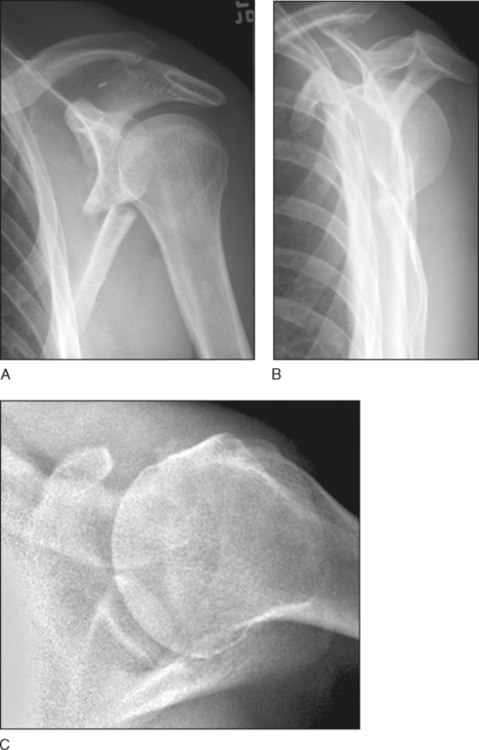

♦ Figure 4A–C shows an anterior rim fracture with loss of glenohumeral alignment in a 36-year-old male who sustained this injury while skimboarding, when he noticed his shoulder dislocate and self-reduce (Case 2).

• In contrast to type I, true glenoid fossa fractures (types II–VI; see Surgical Anatomy) follow a more centrally applied lateral force producing, in most cases, a transverse fracture of the glenoid, which then extends in one of several directions depending on the direction of the load.

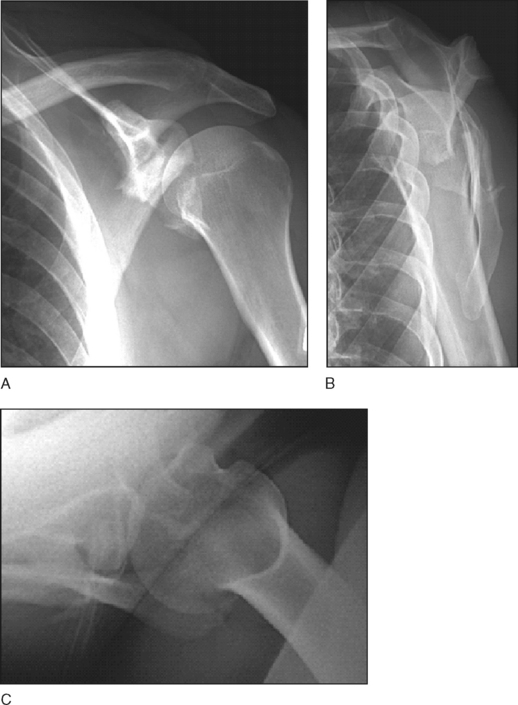

♦ Figure 5A–C shows a displaced extra-articular fracture of the scapula in a 31-year-old overhead worker (electrician) who sustained this injury while mountain biking (Case 3). He has a significant past history of an acromioclavicular joint injury treated with late distal clavicle resection.

♦ Figure 6A–C shows a displaced comminuted, intra-articular fracture of the scapula (glenoid fossa type VI) in a 39-year-old male who sustained this injury catching his front wheel and falling from his bicycle (Case 4).

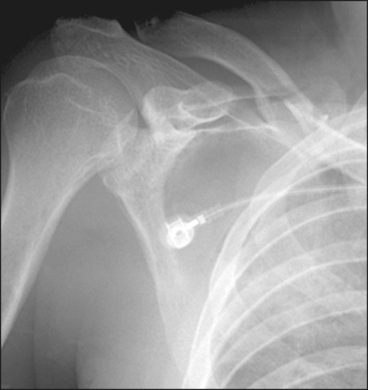

♦ Figure 7 shows a displaced intra-articular transverse fracture of the glenoid fossa (type III) with associated clavicle and first rib fractures in a 36-year-old male triathlete who sustained this injury while road cycling (Case 5). He was neurovascularly intact with symmetric blood pressure in both upper extremities.

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY AND MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Two-dimensional CT reconstruction may be useful in preoperative assessment if done in orthogonal planes to the glenoid to assess fragments and their relative displacement.

Two-dimensional CT reconstruction may be useful in preoperative assessment if done in orthogonal planes to the glenoid to assess fragments and their relative displacement.• Figure 8A–C shows two-dimensional CT views of the large anterior rim injury sustained by the skimboarder in Case 2.

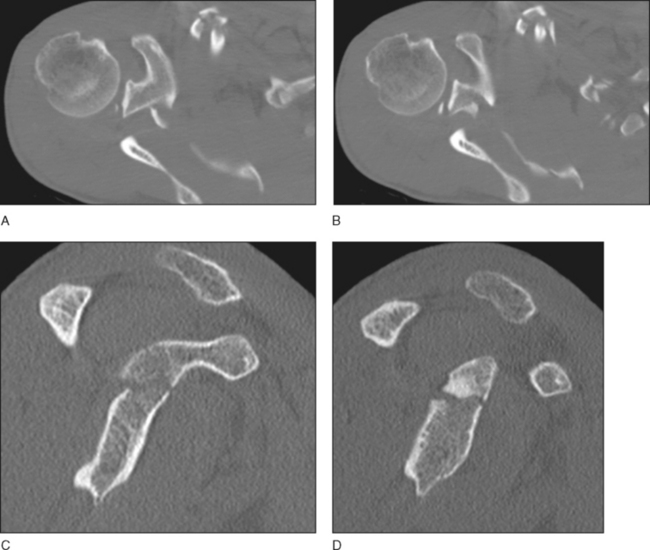

• Figure 9A–D shows two-dimensional CT views of the type III injury sustained by the triathlete in Case 5.

Axial CT slices with three-dimensional reconstruction are the most useful modality in fracture assessment and preoperative planning. Centers could decide to make these part of chest trauma CT studies (time, resource utilization, radiation minimization).

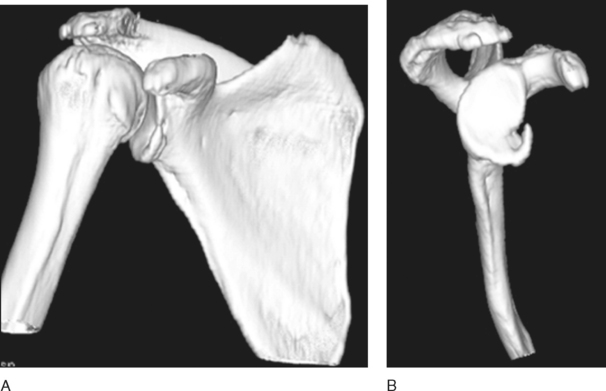

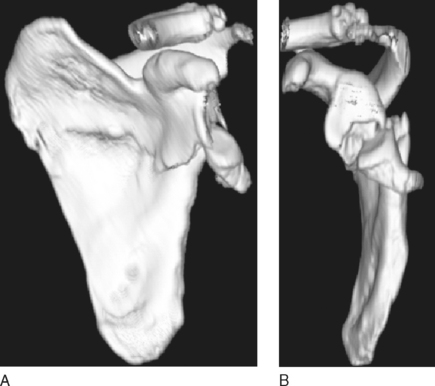

Axial CT slices with three-dimensional reconstruction are the most useful modality in fracture assessment and preoperative planning. Centers could decide to make these part of chest trauma CT studies (time, resource utilization, radiation minimization).• Figure 10A and 10B shows three-dimensional CT views of the small anterior rim injury sustained by the 63-year-old accountant in Case 1.

• Figure 11A and 11B shows three-dimensional CT views of the large anterior rim injury sustained by the skimboarder in Case 2.

• Figure 12 show a three-dimensional CT view of the extraarticular glenoid neck/body fracture sustained by the mountain biking electrician in Case 3.

• Nonoperative treatment is advocated for undisplaced/minimally displaced fractures, severely comminuted unreconstructible fractures (when stable fixation cannot be expected), and cases in which no functional use of the limb is expected.

• Operative care includes open techniques, closed reduction and percutaneous fixation techniques, and arthroscopically assisted techniques. Figure 14A and 14B shows postoperative radiographs confirming preserved glenohumeral alignment of the anterior rim fracture in the 63-year-old accountant in Case 1.

• Figure 13A and 13B shows three-dimensional CT views of the type VI injury sustained by the bicyclist in Case 4.

Magnetic resonance imaging may be of value in detecting associated rotator cuff tears or ligament injuries; however, it is not practical in an acute trauma setting.

Magnetic resonance imaging may be of value in detecting associated rotator cuff tears or ligament injuries; however, it is not practical in an acute trauma setting.