Section 2. Assessment and diagnosis of the injured athlete

Introduction40

Examination of peripheral joints41

Common injuries in the upper limb46

Common injuries in the lower limb69

Examination of the spinal region108

Common injuries in the spine120

Introduction

The purpose of this pocketbook is not to be a definitive text on musculoskeletal examination; there are plenty of other texts that deliver this very well. Instead we present the fundamental principles that apply to both the subjective history and objective examination for most peripheral joints and a basic screen for spinal examination. Also included are special questions and tests for specific anatomical areas and injuries. Any of these examinations should detect the majority of common injuries in both the acute and chronic presentations, but they will not pick up every single pathology. The fundamental principles will be covered in this section and special questions and tests will be covered in the injury-specific sections.

We use a novel approach to the injury-specific sections. Clinical reasoning in patient management requires the clinician to generate a number of possible diagnostic hypotheses which are then “tested” using the patient’s responses to both subjective questioning and physical examination. Through interaction with clinicians, the authors have recognized that identifying diagnostic hypotheses is often difficult. The injury-specific section describes several diagnostic possibilities for each region, against which the clinician can test and compare their patient’s presentation. Whilst we all know that two individuals presenting with the same condition will rarely present with exactly the same features, familiar patterns present both in the history and examination. Some of these patterns are more common than others and we have used our years of clinical and teaching experience in an attempt to allocate how frequently these occur in order to assist typical pattern recognition of these injuries. We employ the following tick system to give a rough idea how frequently these signs and symptoms present:

Two other issues to bear in mind when you are using the injury-specific sections:

1. The degree of injury. This could be mild–severe, Grade 1–Grade 3; however you want to classify it. Unless it is indicated otherwise (e.g. rupture of the Achilles tendon) we have accounted for injuries in the middle of the injury spectrum.

2. The timing of your examination. In the acute phase, if you are pitchside and get to examine the athlete straight away, you are more likely to get positive tests where positive tests exist. Examination of the same athlete in the clinic 24–48 hours later may not elicit the same positive signs if sufficient pain and swelling has developed. In this situation it might not be possible to complete a full examination until the acute stage has settled. In the chronic stage this may be not so much of an issue.

Examination of peripheral joints

Subjective history

Taking a good subjective history is a skill that needs to be developed – try and ask open questions and avoid any leading questions. If at the first time of asking you do not have all the information you were seeking, try and paraphrase the question without giving too much information. For example, “can you tell me what your problem is?” i.e. do not presume it is pain that is the problem here – you want to hear the description of their problem in their own words without any autosuggestion of what they should be experiencing or telling you.

A detailed history is important to establish what you are dealing with and you need to determine the following:

1. Differentiate whether you are dealing with an acute or chronic injury.

2. Is it a traumatic or overuse injury?

3. Establish the mechanism – was it a contact or non-contact injury?

4. Did any swelling occur? Where, how quickly and how long did it take to resolve?

5. What are the problems now?

• Location of symptoms – localized or vague? Can they put their finger on it or do they generally rub an area with the palm of their hand? This may be important to differentiate localized or referred pain

• Nature of symptoms. Pain – sharp, dull/ache; deep/superficial?

• Severity? A patient specific activity VAS scale out of 10 (Form 2.1)

Form 2.1

This useful questionnaire can be used to quantify activity limitation and measure functional outcomes for patients with any orthopaedic condition

Initial assessment:

I am going to ask you to identify up to three important activities that you are unable to do or are having difficulty with as a result of your _________________ problem. Today, are there any activities that you are unable to do or having difficulty with because of your _________________ problem? (Clinician: show scale to patient and have the patient rate each activity.)

Follow-up assessments:

When I assessed you on (state previous assessment date), you told me that you had difficulty with (read all activities from list at a time). Today, do you still have difficulty with: (read and have patient score each item in the list)?

Patient specific activity scoring scheme (point to one number):

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Unable to | Able to perform | |||||||||

| perform | activity at the | |||||||||

| activity | same level as | |||||||||

| before injury or | ||||||||||

| problem | ||||||||||

(Date and Score)

| Activity | Initial | |||||

| 1. | ||||||

| 2. | ||||||

| 3. | ||||||

| 4. | ||||||

| 5. | ||||||

| Additional | ||||||

| Additional |

Total score = sum of the activity scores/number of activities

Minimum detectable change (90% CI) for average score = 2 points

Minimum detectable change (90% CI) for single activity score = 3 points

PSFS developed by: Stratford P, Gill C, Westaway M and Binkley J (1995) Assessing disability and change on individual patients: a report of a patient specific measure. Physiotherapy Canada 47:258-263.Reproduced with the permission of the authors.

• Behaviour of symptoms − intermittent or continuous? Need to differentiate between mechanical and chemical pain. In the acute inflammatory stage where a chemical response is underway there may well be continuous pain. In the absence of an acute injury, continual pain is not normal and is indicative of:

– Serious pathology

– Psychosocial factors

– Do the symptoms occur on a daily basis? Try and establish if there is any pattern

– Red flags – check for night pain

6. Irritability – how easily are the symptoms provoked and how quickly once provoked do these settle down? If the irritability is high, this might guide your choice and order of examination techniques. Establish the aggravating and easing factors – the mechanics of these may help indicate what the problem is and also how to manage it. An example of highly irritable back pain may take 5 minutes of sitting to flare it up and then they may have to lie flat for 2 hours for it to settle. Compare this with an example of knee pain that takes all day walking around to come on and will then ease off after sitting down for 5 minutes

7. Family history

8. Medication history

9. Social history

At the end of the subjective examination an experienced clinician should be approximately 80% certain of what they are dealing with and will tailor the physical examination accordingly to prove and/or disprove this working hypothesis.

Physical examination

For peripheral joints, the contralateral limb should be used for comparison as long as there are no problems with the other side. Always assess the contralateral limb first so the athlete knows what you are about to do and what it should feel like before testing the injured side.

From the subjective examination you should know the nature, severity and irritability of the condition and what tests are likely to provoke any symptoms. The order of the examination may need to be modified to take this into account.

Observation

Biomechanical evaluation in standing and walking (Table 2.1). Check for swelling and temperature changes if necessary.

| Note: Analysis of running should ideally be done on a treadmill with a video camera. |

1. What you need to do? 2. What do your findings mean in relation to the presentation? Picking out biomechanical anomalies is easy – most people have them. The KEY feature is linking these to the athletes sign and symptoms (see example in patellofemoral knee pain, page 84). 3. Can you change the signs and symptoms by altering the biomechanics? |

| Part 1: Static Evaluation |

In weight-bearing: Pelvis: In anterior or posterior tilt? If yes, are there any compensatory changes? Hip: Femoral anteversion: Craig test Knee: Varus/valgus/hyperextended Foot: Position: Forefoot pronation or supination; Rearfoot calcaneal eversion |

| Part 2: Dynamic Evaluation |

Step-up and Step-down Observation during task: (i) change in spinal position (ii) pelvic position (iii) hip abd/add/rotation (iv) dynamic knee valgus (v) patella position relative to the femur (vi) foot position |

Active ROM

It is obviously important to see how much movement there is, but perhaps more crucial is to see how willing the athlete is to move the limb, the quality of the movement and to then note the onset of any pain.

Passive ROM

The joint or muscle being tested should be taken to end of range and overpressure applied. The examiner evaluates the range of movement, when resistance occurs during range, the end feel and presence of any pain reported.

Resisted muscle test

The muscle to be tested should be put into mid-range and tested isometrically in the first instance. The examiner should try and ensure that minimal movement occurs during the test and the muscle is tested maximally. The examiner is evaluating for the presence of pain and/or weakness.

Ligament tests

The basic principle for ligament testing is that the examiner should know the anatomy of the ligament to be tested. The joint should be placed in the optimal position to test the ligament and then taken to the end of range to “wind” the ligament up, and overpressure applied. The examiner is evaluating for the presence of laxity and/or pain. The most common ligament injuries are covered in the injury-specific section.

Special tests

These will include anything that does not strictly fit into the other categories.

Functional tests

These should be specific to the presentation and structure being tested. For example, if an athlete presents with anterior knee pain which comes on after running for a mile and little is found on examination, then you may need to send them out to run for a mile and then reassess them. Functional tests should be selected for sport specificity and the stage of the pathology. Additionally, these can be quite provocative, e.g. triple leg cross-over hop (see Fig 4.3), and therefore should be introduced incrementally starting with lower demand tests and progressing appropriately.

At the end of examination you should have established a working diagnosis and a management plan which may consist of further investigation and conservative or surgical management.

Common Injuries in the Upper limb

Shoulder

Acute shoulder injuries

Glenohumeral dislocation

The shoulder is the most commonly dislocated joint. Shoulder dislocation is one of the most common traumatic injuries in sport and occurs frequently in contact sports such as rugby or judo. It can occur in a posterior or inferior direction, but 95% of dislocations occur anteriorly.

Subjective:

Anterior dislocation occurs when the arm is positioned in abduction and external rotation – may be associated with external force from an opponent or a fall ✓✓✓

Immediate, severe pain associated with the injury. The athlete describes a sensation of the shoulder “popping out” ✓✓ ✓

Unable to play on ✓✓✓

Pins and needles, numbness or discoloration through the arm to the hand in the presence of damage to nerve or blood vessels ✓✓

Subsequent feeling of instability or episodes of giving way in the absence of pain ✓✓✓

Objective:

Obvious deformity – head of humerus sitting anteriorly – normal shoulder contours lost ✓✓✓

Active and passive movement – limited by pain and severe muscle spasm ✓✓✓

Patient holds shoulder supported close to the body and resists movements, especially into abduction/external rotation ✓✓

Positive apprehension sign ✓✓✓ (Fig 2.1). This testing is only undertaken in an athlete with chronic symptoms. In acute cases, pain and muscle spasm will prevent the therapist from being able to position the shoulder for testing

Associated injury:

Bankart lesion – tear of the glenoid labrum

Bony Bankart – glenoid fracture associated with labral tear

Hills–Sachs lesion–cortical depression in the head of the humerus as a result of impaction of the humeral head against the anterior inferior glenoid rim

The presence of any of these associated injuries increases the likelihood of recurrent dislocations

Management: (see also Case Study in Section 3 p 213)

Do not attempt to reduce the dislocation on field

Immediate management – sling support/pain relief/medical attention to relocate the joint

Immobilization – external rotation vs. internal rotation

Athletes are initially managed with a conservative rehabilitation programme aimed at improving rotator cuff and shoulder strength and control. The clinician should have a limited tolerance/low threshold for surgical review in elite athletes or people playing contact sports if conservative management does not reduce sensations of instability and apprehension

Presence of instability 3 months after injury would suggest a need for surgical intervention to prevent recurrent dislocations in active individuals

Older athletes, with stiffer shoulders, are less likely to have recurrent symptoms and may manage with a conservative approach

Acromioclavicular joint sprain

Acromioclavicular (AC) joint strains are thought to account for about 40% of all shoulder injuries and almost always occur as a result of either a fall onto the shoulder or the outstretched hand (cycling, judo, horse riding) or a direct blow to the shoulder (contact sports) ✓✓✓

Subjective:

Significant, superficial pain localized to the region of the AC joint ✓✓✓

Difficulty with elevation movements above 60° – degree of limitation dependent upon the severity of the injury ✓✓

Difficulty sleeping on the affected shoulder ✓✓✓

Objective:

Pain and swelling directly over the AC joint ✓✓✓

Step deformity − between the clavicle and acromion ✓

Active movement – limited by pain ✓✓

Full range of passive glenohumeral motion ✓✓✓

Specific tenderness on palpation of AC joint ✓✓✓

Investigations:

An X-ray may be ordered to rule out a fracture and determine the extent of the joint separation

Management:

Immediate management – sling support and pain relief − PRICE (Protection, Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation)

Physiotherapy is often not necessary in the case of mild sprains, but may be required in the case of higher grades of injury or in cases where the athlete is slow to regain range of motion and function. In these instances, manual therapy will be required to regain shoulder mobility, with appropriate strength and control exercises used concurrently

In very rare cases surgery may be required

Rotator cuff tear

Most rotator cuff tears occur as a result of overuse and tend to occur in people over the age of 40 ✓✓✓

Acute tears of the cuff are the result of trauma and may occur in association with other injuries or excessively forceful activation of the muscle group in a long lever situation (gymnastics/kayaking)

Subjective:

Sudden onset of pain over the region of the deltoid insertion (referred pain) ✓✓✓

Pain settles reasonably quickly within a few days ✓✓

“Popping” sensation in the shoulder associated with the injury ✓

Immediate onset of weakness associated with shoulder elevation—dependent upon the severity of the injury ✓✓

Objective:

Painful and limited shoulder elevation (flexion and abduction) ✓✓

Poor movement pattern of elevation with excessive scapular motion to compensate for inefficient glenohumeral motion ✓✓✓

Non-specific tenderness on palpation over the region of the rotator cuff – often difficult to localize tear ✓✓

Specific tests:

Muscle strength tests for the isolated muscle will indicate which element of the cuff is torn

NB: In the acute stage all tests may be pain inhibited

Management:

PRICE

Passive/assisted active range of motion exercises – to maintain mobility and avoid shoulder stiffness

Graduated strengthening exercises targeting the rotator cuff

Chronic shoulder injuries

Shoulder impingement

This is a very general term that describes the etiological process, in which an element of the rotator cuff musculature is “impinged” between the humeral head and the acromion during elevation activities. It is therefore common in athletes involved in repetitive overhead activities. Shoulder impingement is usually described as either primary, where the cause of the impingement is a structural anomaly of the shoulder or secondary, where the impingement occurs because of poor motor control around the shoulder. In this way, an overlap between secondary shoulder impingement and instability exists and the two often occur concurrently ✓✓

Examples of primary causes include an altered acromial shape or bony spurs as a result of degenerative changes.

Subjective:

Minor pain in the shoulder region at rest, increased significantly with elevation movements ✓✓✓

Pain localized to the anterior/ lateral shoulder only extending as far as the deltoid insertion and not into the trapezius region ✓✓✓

Pain and restriction with hand behind back movements ✓✓

Difficulty lying on the affected shoulder at night ✓

Objective:

Patient’s symptoms reproduced with active flexion and abduction – arc of pain from 80° to 120° ✓✓✓

Full passive range of motion ✓✓✓

Motion restricted primarily by pain rather than stiffness ✓✓✓

Active movements which are painful can be performed painfree passively ✓✓

Minor strength deficits ✓

NB: Suspect a cuff tear in any case with significant weakness

Investigations:

In cases of primary impingement, an X-ray (outlet view) is useful in determining whether degenerative changes exist in the AC joint that may be contributing to the impingement

Special tests:

There are several tests for impingement (Neer, Hawkins–Kennedy) and all are designed to reproduce the compression of the rotator cuff between the bony elements (Fig 2.4)

Copeland’s test (an extension of Neer’s test) − abduction in the scapula plane with the shoulder in internal rotation causes mid-arc pain which is abolished with abduction in external rotation ✓✓✓

Neer’s test, in which an athlete’s impingement pain is abolished on administration of a subacromial injection of local anaesthetic, can be useful in confirming the source of pain, but will not help direct treatment

Associated injury:

Secondary impingement is defined as rotator cuff impingement that occurs secondary to a functional decrease in the supraspinatus outlet space due to underlying instability/poor motor control of the glenohumeral joint. It is a more common cause than the presence of degenerative changes in young athletes, and should always form part of the examination process

Ongoing impingement may result in:

• Microtrauma to the tendon and inflammatory changes

• Bursitis

• Calcific tendonitis

In older athletes, rotator cuff tears may result from ongoing impingement

Management: (see also Case Study in Section 3 p 222)

Correction of motor control deficits – scapular or glenohumeral joint

– rotator cuff rotational control

Soft tissue techniques:

Subacromial injection often useful to provide “window of opportunity” for rehabilitation to be effective. Settles inflammatory response

Surgery usually indicated in cases of primary impingement

Shoulder instability

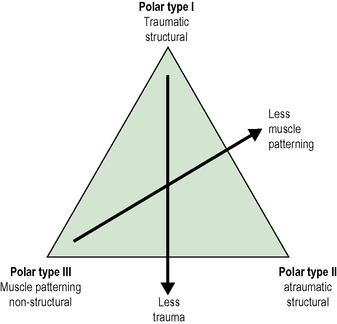

Shoulder instability is a common sporting problem with multiple manifestations that can make its management complex. Numerous classification systems exist. The Stanmore classification is useful in recognizing the spectrum of presentations (Fig 2.7).

|

| Fig 2.7 With permission from www.shoulderdoc.co.uk. |

This suggests that there are three broad reasons why shoulders present with symptoms of instability. Firstly, a structural problem exists, either because the capsuloligamentous structures have become deficient as a result of major injury (traumatic structural), or secondly, already slightly compromised structures have been subjected to repetitive microtrauma that has led to a loss of stability (atraumatic structural). The third broad reason is an alteration in muscle recruitment around the shoulder complex (scapulothoracic/glenohumeral) causing a loss of the ideal orientation of the glenoid and humeral head in relation to each other during movement (muscle patterning).

Degrees of overlap of pathology and therefore signs and symptoms exist that require careful history-taking and examination to determine the presence or absence of each component.

The three broad categories will be discussed below

Subjective:

Traumatic structural

Significant trauma ✓✓✓

Unilateral symptoms ✓✓✓

Dislocating position – abduction/external rotation − anterior ✓✓✓

Unable to self relocate

Atraumatic structural

Common in throwers and swimmers where shoulder is subjected to overload/fatigue – develop microtrauma

Recurrent ✓✓

Minor activity – associated with sensation that shoulder has “popped out” ✓✓✓

Patient reports certain positions that result in dislocation/subluxation ✓✓✓

Bilateral ✓✓

Self relocate/require minimal assistance ✓✓✓

Muscle patterning

Recurrent ✓✓

Bilateral ✓✓

Able to “dislocate” voluntarily – “party trick” ✓✓

Painless dislocation ✓✓✓

Self relocate/require minimal assistance ✓✓✓

Objective:

Traumatic structural

Significant muscle spasm

Atraumatic structural

Positive test for ligamentous laxity ✓✓✓

Evidence of overload/fatigue of shoulder stabilizing muscles ✓

Muscle patterning

Ligamentous laxity testing NAD ✓✓✓

Able to “dislocate” voluntarily – “party trick” ✓✓

Abnormal pattern of shoulder control – scapulo-humeral ✓✓✓

Management:

PRICE

Multidisiplinary team approach essential

Traumatic structural

Reduction of dislocation in A&E

Sling – 2/3 weeks ± painkillers/NSAIDS

± physiotherapy rehabilitation – ROM and strength

Emphasis on proprioceptive re-education

Severe/recurrent – Repair of Bankart lesion

Atraumatic structural

Rehabilitation – motor control

Proprioceptive retraining

Address areas of soft tissue/joint restriction – commonly posterior capsule

Muscle patterning

Rehabilitation aimed at addressing the sequencing pattern of muscle activation – commonly the large muscles of the glenohumeral joint – latissimus dorsi/pectoralis major/deltoids are overactive

Soft tissue work

Address control of glenohumeral joint movement with rotator cuff control

Need to review entire kinetic chain – often poor posture generally – trunk control

Rotator cuff tear

Athletes with chronic cuff damage are usually over the age of 40 ✓✓✓. They often complain of a history of minor shoulder pain and irritation that worsens suddenly as the result of a minor incident or period of excessive activity in which the arm is raised above shoulder height.

Subjective:

Affected shoulder is the dominant arm ✓✓✓

Pain has gradually got worse over time – difficult to localize – most specific in the region of the deltoid ✓✓✓

Restriction to shoulder function due to pain and weakness ✓✓✓

Night pain – unable to lie on affected shoulder ✓✓✓

Objective:

Painful limitation of elevation movement with associated weakness ✓✓✓

Poor movement pattern of elevation with excessive scapular motion to compensate for inefficient glenohumeral motion ✓✓✓

Other movements affected by long-standing changes in cuff function and control ✓✓✓

Non-specific tenderness on palpation over the region of the rotator cuff – often difficult to localize tear ✓✓

Management:

Pain control – may benefit from local injection therapy (local anaesthesia and corticosteroid) to reduce inflammatory changes and pain inhibition in order to provide a window of opportunity for rehabilitation

Graduated cuff control exercises – focus on rotation and control with elevation movements

Specific scapular re-education is necessary if shoulder dysfunction has been present for some time

Surgery may be required if conservative management has failed (large tears) or if the patient has high demands from the shoulder for work or sporting activities

C5 shoulder syndrome

The C5–6 vertebral motion segment is the level most commonly involved in the development of neck and upper limb symptoms. This is probably due to gravitational effects and altered postural alignment. Clinicians treating athletes with upper limb pain often fail to examine the cervical spine  adequately, especially when the athlete’s symptoms are reproduced with movements of the arm.

adequately, especially when the athlete’s symptoms are reproduced with movements of the arm.

Subjective:

Pain in the shoulder and upper arm region ✓✓✓

Dull, aching quality of pain – mimics pain from the somatic structures of the shoulder ✓✓✓

Symptoms aggravated by movements of the arm and shoulder, especially elevation above 90° ✓✓✓

No reported neck pain or other symptoms ✓✓

Objective:

Active cervical movement tests all NAD including overpressure ✓✓✓

Neurological assessment NAD

Hypomobile and tenderness present on manual segmental examination of C5–6 vertebral level – unilateral and comparable with the side of symptoms ✓✓✓

Management:

Manual therapy – mobilization ± manipulation directed to C5–6 level

Correction of upper quadrant movement dysfunctions – important to examine the relationship between spinal movement and upper limb movement and control. Address cervical control, scapular control and rotator cuff function

Elbow

Lateral elbow pain

Lateral elbow pain is commonly referred to as “tennis elbow”, but this entity is certainly not restricted to tennis players. It is also known as “lateral epicondylitis”, but given the current understanding of the underlying pathology, the term “tendinosis” would be more appropriate.

Subjective:

Acute or insidious onset ✓✓✓

Pain with activities requiring gripping ✓✓✓

Localized or diffuse symptoms ✓✓✓

Objective:

Resisted wrist extension – pain ✓✓✓

Palpation – tenderness over ECRB tendon ✓✓✓

Special tests:

Associated injury:

Check no cervical spine involvement

Management:

Eccentric exercise programme (see Alfredson protocols for jumpers’ knee and Achilles tendinopathy for frequency and duration of exercises, page 96)

Sport specific – check technique and racquet grip size, weight and string tension

Treat any neural/spinal involvement

Bracing – epicondylar clasp

Many more invasive treatments have been suggested when conservative management is unsuccessful (see Achilles tendinopathy) including injections (corticosteroid, autologous blood, sclerosant), extracorporeal shock wave therapy or surgery. The evidence regarding their efficacy is mixed

Medial elbow pain

Medial elbow pain can be separated into two different entities. The first involves overactivity of the wrist flexors and has been referred to as “golfer’s elbow”. The second has been more commonly termed “thrower’s elbow”. During this action, especially during the cocking and acceleration phases, the valgus load puts a stress on the MCL and compresses the radio-humeral joint.

“Golfer’s” elbow

Subjective:

Pain with activity ✓✓✓ (golf or heavy top spin on the forehand in tennis)

Objective:

Resisted wrist flexion – pain ✓✓✓

Resisted pronation – pain ✓✓✓

Palpation – tenderness over medial epicondyle ✓✓✓

Special tests:

Associated injury:

Check no cervical spine involvement

Management:

See lateral elbow pain

“Thrower’s” elbow

Subjective:

Pain with activity ✓✓✓ (common in baseball pitchers and javelin throwers)

Objective:

Associated injury:

Osteochondral damage to the radio-humeral joint

Management:

Sport specific – check technique

Taping

Strength and conditioning of forearm flexors and pronators

Wrist and hand

Triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) injury

The TFCC is a small piece of cartilage that separates the ulnar from the carpal bones and is integral to ulnar-carpal stability. Disruption to this complex may be acute or chronic. It occurs in high-velocity sports such as boxing and gymnastics, and hockey and racquet sports.

Subjective:

Pain on the ulnar side of the wrist with activity ✓✓✓

Clicking sound or sensation or clunking in the wrist ✓✓

Objective:

Ulnar swelling in the acute presentation ✓✓

Local tenderness ✓

Investigations:

MR Arthrography is the gold standard for diagnosis

Associated injury:

Differential diagnosis – extensor carpi ulnaris tear

Management:

Bracing

Arthroscopic surgical repair

Scaphoid–lunate dissociation

This is easy to miss and should be suspected in a case of chronic persistent wrist pain. It is caused by disruption of the scapholunate ligament and leads to instability/subluxation of the scaphoid, it is the most common carpal instability.

Subjective:

Acute traumatic episode ✓✓✓

Forced hyperextension of the wrist ± ulnar deviation ✓✓

Subsequent pain with activity ✓✓✓

Clicking/clunking in wrist ✓

Objective:

Tenderness over scapholunate border just distal to Lister’s tubercle ✓✓✓

Grip strength – weakness ✓

Investigations:

Stress X-ray: AP view with a clenched fist reveals a gap between the lunate and scaphoid – the “Terry Thomas” sign in the presence of this condition ✓✓✓

Special tests:

Scaphoid shift test: palpate scaphoid tuberosity whilst moving the wrist from ulnar to radial deviation. This manoeuvre will be painful in this condition ✓✓ (Fig 2.14)

Associated injury:

Radial styloid fracture

Scaphoid fracture

Management:

Surgical repair. Delayed repair leads to degenerative changes

Skier’s thumb

This used to be called gamekeeper’s thumb and is a traumatic injury to the ulnar collateral ligament of the first metacarpal joint, now more often seen in skiers.

Subjective:

Fall where the thumb is forced into abduction and extension ✓✓✓

(The thumb can be forced into this direction during a fall whilst holding a ski pole or if the thumb gets caught in the strap of the pole)

Immediate pain localized to the medial aspect of the thumb ✓✓✓

Objective:

Management:

Complete tear with excessive joint laxity requires surgical repair

Incomplete tear – immobilization with tape or splint for 4−6 weeks

Common Injuries in the Lower limb

Hip/groin and thigh

Groin pain

Groin pain is common in athletes especially in sports that involve twisting and kicking. Groin pain is also notoriously difficult to diagnose; symptoms are often recurrent and it is one of the major causes of lost playing time in sports like football and rugby. Many structures can be implicated and pathologies may co-exist, and there are no consistent patterns of presentation. Differential diagnosis includes hip joint pathology (labral pathology, chondral injury, osteoarthritis), inguinal hernia, adductor related pain (tendinopathy, enthesopathy, MT junction), nerve entrapment (ilioinguinal, obturator, genitofemoral), stress injury to the pubic bone, rectus abdominis strain, conjoint tendon tear, external oblique tear, iliopsoas syndrome, stress fracture neck of femur (NOF), referred lumbar pain (L1/2).

Subjective:

Pain:

Insidious or sudden onset

Localized or diffuse

Superficial or deep

Aggravated by activity ✓✓✓ NB: In many cases symptoms may have a latent response. Activity may not increase symptoms at the time, but an increased response is evident on objective testing

Objective:

Sensation – check

Hip range of motion (ROM) – can be reduced

Length and strength ± pain response (Table 2.2). Palpate where possible: resisted sit-up (rectus abdominis), adductor longus, iliopsoas, piriformis, trunk rotation (external oblique – opposite side)

| Muscle | Length | Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Rectus abdominis | N/A | Sit-up |

| External oblique | N/A | Trunk rotation |

| Adductor longus | Often tight | Squeeze test (Fig 2.16) Resisted adduction in Thomas test position |

| Iliopsoas | Thomas test: often tight (Fig 2.17) | Hip flexion in Thomas test position |

| Piriformis | Often tight |

Often poor lumbo-pelvic control – anterior tilt/increased hip flexion

Special tests:

Femoral slump test

Valsalva manoeuvre – inguinal hernia

Hop test – stress fracture inferior pubic ramus

If few positive signs are elicited during the physical examination you may want to repeat the examination after training or competition.

Associated injury:

See differential diagnosis above – most common cause of groin pain in athletes is hip joint, pubic (males), psoas or adductor related pathology

Management:

Rehabilitation programme should be sign-driven, based on response to objective testing, rather than on symptom response

Stretch/mobilize any tight structures; correction of any muscle imbalance/fatigue/weakness issues (often gluteals/hip abductor weakness) NB: Avoid stretching the adductor muscles. More effective to use soft tissue techniques to reduce tension in this muscle group

Graduated rehabilitation programme – with particular reference to progression from straight line to twisting activities

If no improvement after relative rest, correction of any dysfunction and graduated rehabilitation and return to play, investigations are warranted

Investigations:

MRI or LA injection, nerve conduction studies if indicated. Ultrasound is more sensitive for identifying tears to soft tissue structures in the abdominal wall

Labral tear

Increasingly more recognized as a cause of pain in athletes in sports requiring turning, twisting and kicking. With improvements in MR imaging of the hip joint, increasing identification of labral tears is occurring. An anterior tear is the most common type and may present acutely or chronically. The symptoms can present in many different ways.

Subjective:

Pain maybe felt in either the groin/trochanteric/deep hip or low back ✓✓✓

Dull positional pain unrelated to activity ✓

Only provoked by activity ✓

Sharp catching pain ✓

Objective:

Investigations:

MRI/MRA to confirm diagnosis – but can be missed on scanning

Associated injury:

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) whereby the femoral neck impinges against the acetabular labrum

These two conditions may co-exist or FAI may be a precursor to a labral tear

Differential diagnosis: femoral neck stress fracture if the athlete presents with an insidious onset of groin pain, with an increased index of suspicion with increased training loads or female endurance athletes with disordered eating and menstruation. Fulcrum test and bone scan to exclude this diagnosis

Management:

May resolve spontaneously. Unload the hip as necessary

In professional athletes the first line of treatment is arthroscopic debridement

Need to address biomechanical predisposing factors – anterior translation of femoral head – tight posterior hip capsule/overactive hip external rotators/poor gluteal function – tendency to perform hip external rotation rather than hip extension with gluteals/poor control of hip flexion by iliopsoas and overactive rectus femoris

Quads contusion (dead leg)

Common in contact sports such as rugby. Need to differentiate between a direct blow and a strain. Management for a strain is similar. In young athletes proximal anterior thigh pain may be an avulsion at the apophysis of rectus femoris.

Subjective:

Direct blow to the thigh ✓✓✓

Objective:

Localized anterior thigh pain ✓✓✓

Swelling ✓✓✓

Resisted quads: pain ✓✓✓

Prone passive quads stretch – painful and limited ✓✓✓ ).  (Fig 2.20 NB: Less than 90° knee flexion indicates that the player is likely to be out for several weeks

(Fig 2.20 NB: Less than 90° knee flexion indicates that the player is likely to be out for several weeks

Special tests:

Single leg hop – pain and reduced performance

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree