Partial-thickness Rotator Cuff Tears

Suspicion ain’t proof.

Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears are a common cause of pain and disability in the adult shoulder. Despite this, the indications for various types of nonoperative and operative treatment of partial-thickness tears (e.g., debridement vs. repair) remain controversial. Partial-thickness tears are approximately twice as common as full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff, and they may be associated with significant concomitant pathology including superior labral lesions, biceps pathology, chondromalacia/osteoarthritis, acromioclavicular joint derangement, and adhesive capsulitis. Furthermore, many partial tears may present as incidental magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings and therefore should be correlated to the patient’s history and physical findings.

Partial tears are generally classified by tendon location (e.g., supraspinatus, infraspinatus), anatomic location (e.g., bursal surface, articular surface, interstitial), and the percentage of tendon thickness torn. While no clear consensus exists, the indications for surgical repair of the tendon (following failure of nonoperative treatment) are generally based on the percentage of tendon thickness torn. In patients with a tear involving 50% or more of the tendon thickness, surgical reattachment of the tendon is usually indicated. However, other factors should also be strongly considered and may be more influential than the percentage of thickness torn. These factors include age, activity level, vocation, sports participation, chronicity of symptoms, and associated pathology.

Once surgical repair has been selected, several different surgical repair techniques and configurations may be chosen. The specific technique is largely based upon the pathology at hand.

COMPLETION OF THE TEAR

In a patient with a significant articular-sided partial-thickness rotator cuff tear, converting the partial-thickness into a full-thickness rotator cuff tear is an option. After that, standard arthroscopic rotator cuff repair techniques may be utilized for tendon fixation to bone. We use this technique only when >80% to 90% of the tendon thickness is torn and/or the residual intact rotator cuff tendon tissue is of poor quality with minimal structural integrity. However, in patients with good-quality residual tendon remaining, conversion to a full-thickness rotator cuff tear should be avoided. As will be discussed in the following sections, our strong preference is to preserve as much residual cuff as possible and perform transtendon anchor placement if tissue quality allows.

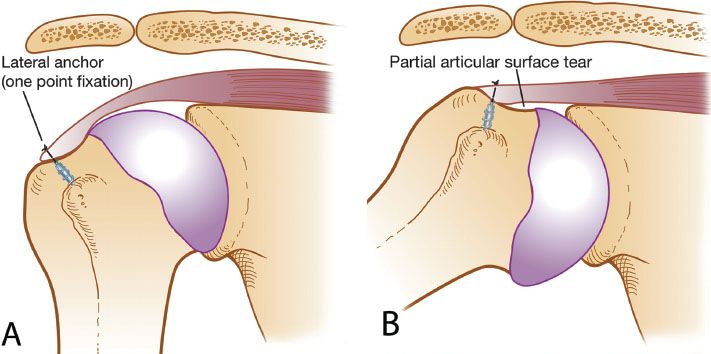

When performing the repair after completion of the tear, a double-row rotator cuff repair should be performed to restore full footprint coverage (1). Since single-row rotator cuff repair results in poor footprint coverage (particularly medially), single-row repair may merely recreate the preoperative partial-thickness tear anatomy (Fig. 5.1). For this reason, a double-row rotator cuff repair should be performed to restore the normal anatomy (Fig. 5.2).

Once the rotator cuff tear has been debrided, its location is marked using a suture. The arthroscope is redirected into the subacromial space and a lateral portal is created. A subacromial bursectomy and decompression are performed and the marking suture is identified in the subacromial space. The integrity of the residual rotator cuff is evaluated, and if it is estimated that >80% to 90% of the tendon thickness is torn, the tear may be completed.

Figure 5.1 Schematic drawing of a single-row suture anchor repair for a partial-thickness articular surface rotator cuff tear (PASTA). A: Point fixation is achieved with only a lateral row repair. B: When the shoulder is abducted, a similar PASTA lesion, with lifting of the medial footprint, is created, despite lateral repair.

A shaver, scissor, or #11 scalpel blade inserted tangential to the footprint may be used to accurately release the residual lateral tendon and potentially preserve as much tendon length as possible. A shaver is subsequently used to debride degenerative tissue that has little residual biomechanical integrity.

A full-thickness tear has now been created and standard rotator cuff repair techniques may be utilized. Bone bed preparation is followed by assessment of the tear mobility and pattern. In most cases, the tear pattern will be crescent and repair will proceed with direct suture anchor repair to bone.

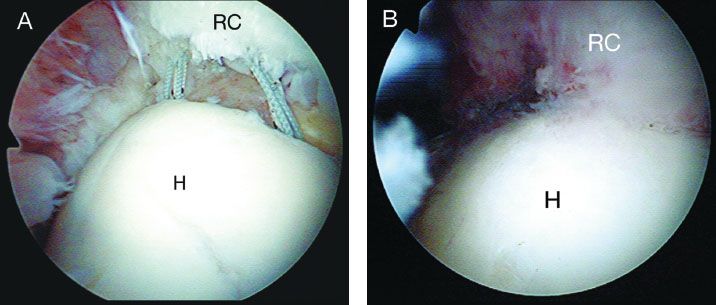

Figure 5.2 Arthroscopic views through a posterior glenohumeral viewing portal of a right shoulder demonstrating a double-row rotator cuff repair, following tying of the lateral row of sutures (A) and following tying of the lateral and medial row of sutures (B). Note: Tying only the lateral row of sutures leaves the rotator cuff elevated off the medial footprint. With tying of the medial sutures, the rotator cuff is compressed against the medial footprint. H, humeral head; RC, rotator cuff.

Figure 5.3 A: Right shoulder, posterior glenohumeral viewing portal, demonstrates use of a curette introduced from an anterior portal to prepare the bone bed for repair. B: Soft tissue has been removed and the bone bed is exposed to a bleeding base to encourage healing following repair. For anterior lesions such as this case, complete preparation can typically be achieved through an anterior portal H, humerus; RC, rotator cuff.

TRANSTENDON ROTATOR CUFF REPAIR OF PASTA LESIONS

In cases where a partial articular surface tendon avulsion (PASTA) lesion has been determined and where significant tendon substance remains, preservation of the intact rotator cuff has several theoretical advantages, including maintenance of the normal length–tendon relationship of the rotator cuff, preservation of the integrity of the glenohumeral joint, provision of an intrinsic source of native tendon cells, and improved biomechanics. In a cadaveric study of similar partial-thickness rotator cuff tears, transtendon rotator cuff repair with preservation of the intact lateral cuff was biomechanically superior to completion of the tear with double-row rotator cuff repair (2).

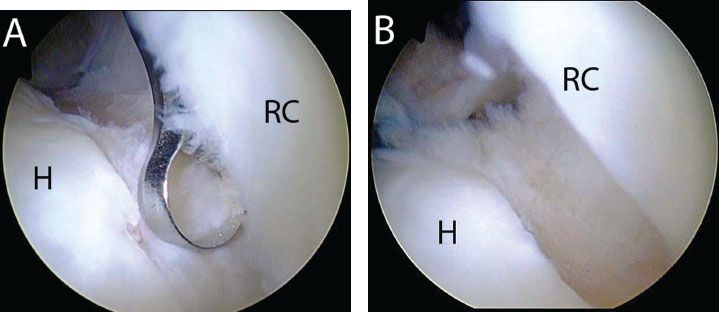

One challenge in transtendon repair is achieving adequate tendon debridement and bone bed preparation in the face of an intact lateral cuff. We typically begin debridement and bone bed preparation with the use of an instrument introduced through an anterior portal (Fig. 5.3). Variations in abduction/adduction and internal/external rotation help deliver the bone bed to the instrument. Posterior access, however, is often limited from an anterior portal because of the convexity of the humeral head. In the setting of a PASTA lesion involving the posterior rotator cuff (i.e., infraspinatus), we commonly work through the rotator cuff lesion. A spinal needle is used as a guide to pass through the lesion with an adequate angle of approach to reach the bone bed. Then, a shaver is walked down the spinal needle and pushed through the rotator cuff (Fig. 5.4). In this way, only a small 4 to 5 mm defect is created in the rotator cuff, allowing debridement and bone bed preparation without completing the rotator cuff tear.

Transtendon repair can be performed with anywhere from 1 to 4 anchors, depending upon the anterior-to-posterior and medical-to-lateral dimensions of the tear. Maybe not essential, but might help orient the ready to these two variables that we highlight later as when to increase the number of anchors.

Single-anchor Mattress

Once a partial-thickness articular surface tear has been debrided, the bone bed is debrided to a bleeding bone surface. The arthroscope is redirected into the subacromial space using the same posterior skin incision and a lateral subacromial portal is established. The subacromial space is then cleared of fibrofatty tissue and bursa and a subacromial decompression with acromioplasty may be performed if indicated. It is critical to completely clear the subacromial space prior to insertion of anchors to facilitate subsequent retrieval and tying of sutures in the subacromial space. Additionally, failure to clear the space first may lead to inadvertent damage to the sutures when a shaver is used to subsequently clear the subacromial space. Following subacromial bursectomy, the rotator cuff is evaluated on its bursal surface.

If significant tendon tissue and quality is present to warrant preservation, a transtendon approach may be utilized. A transtendon repair is generally indicated when 10% to 90% of the tendon thickness remains. In partial articular surface tears with only a small portion of the tendon involved from an anterior-to-posterior direction(i.e., <1.5 cm), a single-anchor mattress technique may be utilized (Fig. 5.5).

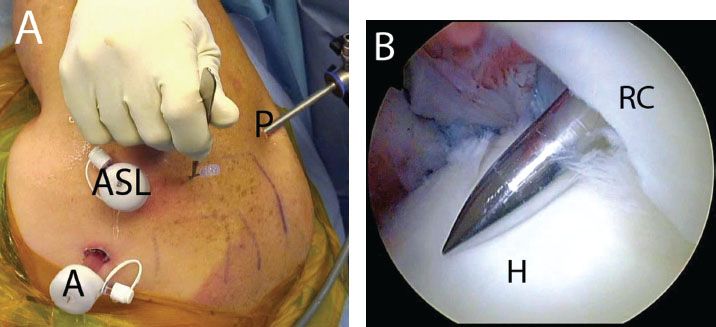

The arthroscope is reintroduced into the posterior glenohumeral portal and the anterior portal is reestablished if necessary. An anchor is then inserted transtendon while viewing through the posterior glenohumeral portal. In some cases, if an anterosuperolateral portal has been created superior and lateral in the rotator interval, the anchor may be placed through the anterosuperolateral portal. However, in many cases, this will not provide the correct angle of approach to the medial aspect of the footprint. To assist in anchor insertion, a spinal needle is used to determine the correct angle of approach (Fig. 5.6). It is important to maintain the position of the needle during the entire anchor insertion step to provide a guide for the correct angle of approach. A skin puncture is then made and a punch is inserted parallel to the spinal needle in a transtendon approach (Fig. 5.7A). To assist in visualization of the punch during impaction, passing the entire punch through the tendon beyond the laser marking prior to bone insertion will dilate the transtendon hole and prevent “sticking” of the rotator cuff against the punch (Fig. 5.7B). The punch is then tapped to its laser marking at the medial margin of the footprint (Fig. 5.7C)

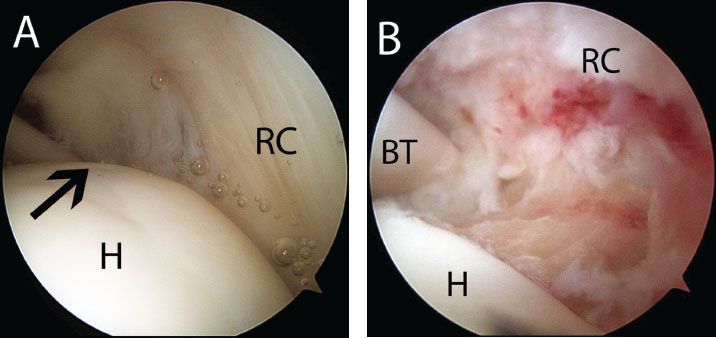

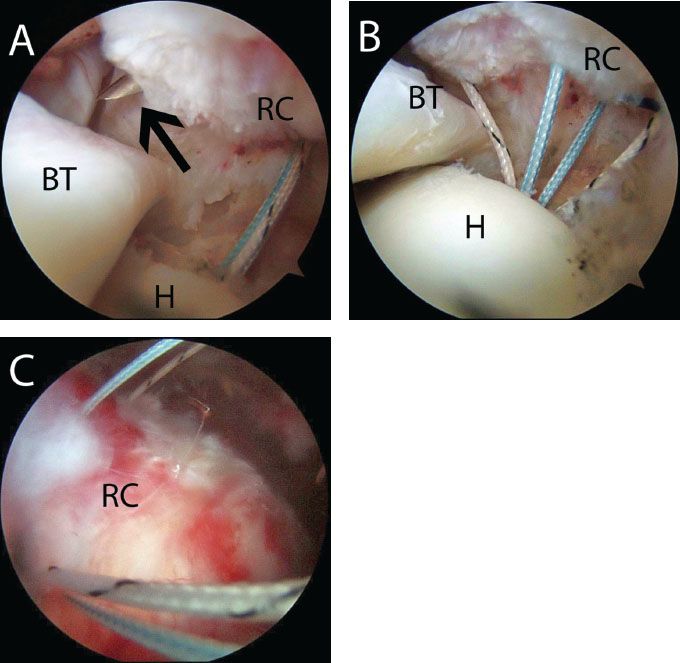

Figure 5.4 Right shoulder, posterior viewing portal demonstrates bone bed preparation of a PASTA lesion with posterior involvement. A: With an anterior working portal, the angle of approach prevents access to the posterior bone bed for preparation. Transtendon preparation is required. B: A spinal needle is used to penetrate the center of the lesion with an angle of approach that allows access to the entire bone bed. C: A shaver is walked down the spinal needle and is used to perform bone bed preparation. BT, biceps tendon; H, humerus; RC, rotator cuff.

Figure 5.5 A: Right shoulder, posterior glenohumeral viewing portal, demonstrates a small PASTA (blackarrow). Note: In this case, the tear is amenable to a single-anchor repair because it only involves a small portion of the footprint in the anterior-to-posterior dimension and the posterior supraspinatus is intact (right). B: Same shoulder demonstrating a prepared bone bed. BT, biceps tendon; H, humerus; RC, rotator cuff.

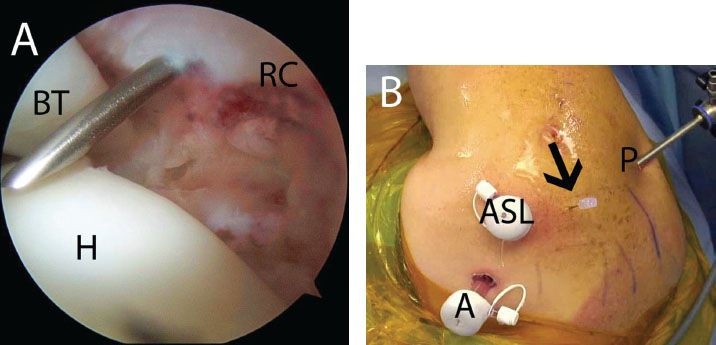

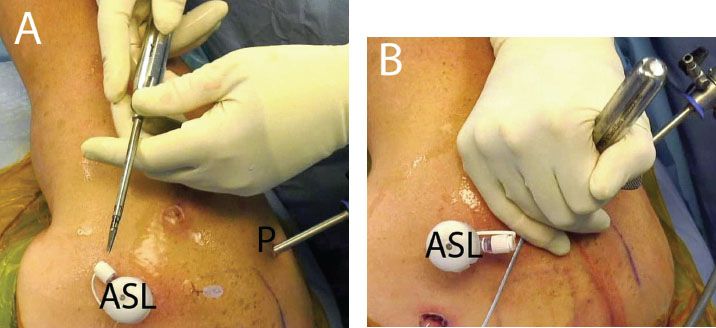

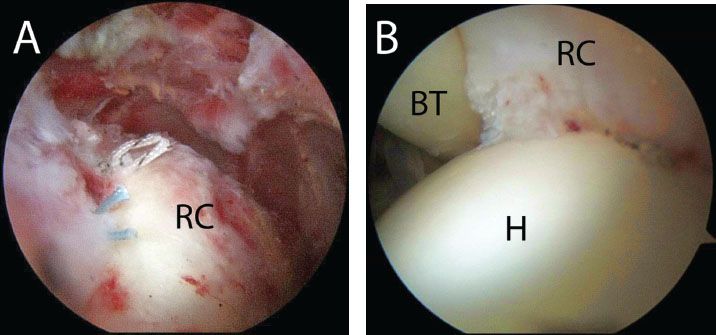

Figure 5.6 A: Right shoulder, posterior glenohumeral viewing portal, demonstrates use of a spinal needle to determine an adequate angle of approach for transtendon anchor placement for repair of a partial-thickness rotator cuff tear. B: External view shows the spinal needle location. A, anterior portal; ASL, anterosuperolateral portal; BT, biceps tendon; H, humerus; P, posterior portal; RC, rotator cuff.

A 4.5-mm BioComposite Corkscrew FT anchor (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) is then passed transtendon through the same hole and inserted into the bone socket (tapping of the bone bed is rarely required) (Fig. 5.7D). A 5.0-mm transtendon metal cannula (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) can simplify anchor insertion by preserving the same channel for insertion of the punch and the anchor (Fig. 5.8). In some cases, it may also be simpler to directly insert a metallic anchor (4.5-mm Corkscrew FT; Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) through the rotator cuff and bone since no punch is required. Once anchor insertion and stability have been confirmed, suture passage proceeds.

Figure 5.7 Punch insertion for transtendon anchor placement in a right shoulder. A: A stab incision is made adjacent to a previously placed spinal needle. B: Posterior glenohumeral viewing portal demonstrates insertion of a punch for bone socket preparation. The punch is inserted beyond the bone bed to dilate the hole in the tendon and prevent the rotator cuff from “sticking” to the punch. C: The punch is withdrawn slightly and positioned for creation of a bone socket. D: An anchor is then placed using the same path as the punch. Note: The spinal needle has been left in place to serve as a guide for insertion of the anchor. A, anterior portal; ASL, anterosuperolateral portal; BT, biceps tendon; H, humerus; P, posterior portal; RC, rotator cuff.

Sutures are passed through the rotator cuff in a mattress fashion. Suture passage may be accomplished in a retrograde manner with a Penetrator (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) (Fig. 5.9), or using a shuttling technique (Micro SutureLasso; Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) (Fig. 5.10). Shuttling is simple, accurate, and minimally traumatizes the rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is penetrated percutaneously through a lateral approach. The shuttle is then advanced through the Micro SutureLasso and one suture limb and the shuttle are retrieved through the anterior portal. The suture is then shuttled through the rotator cuff and out through the skin. The steps are repeated for the other suture limbs creating a spread of mattress sutures.

In either technique, it is important to penetrate the rotator cuff through robust tissue. However, penetrating the rotator cuff too far medially can lead to an oblique passage through the rotator cuff and potentially a bursal-articular surface tension mismatch. Perpendicular passage through the rotator cuff is preferable and may be accomplished by adducting the arm.

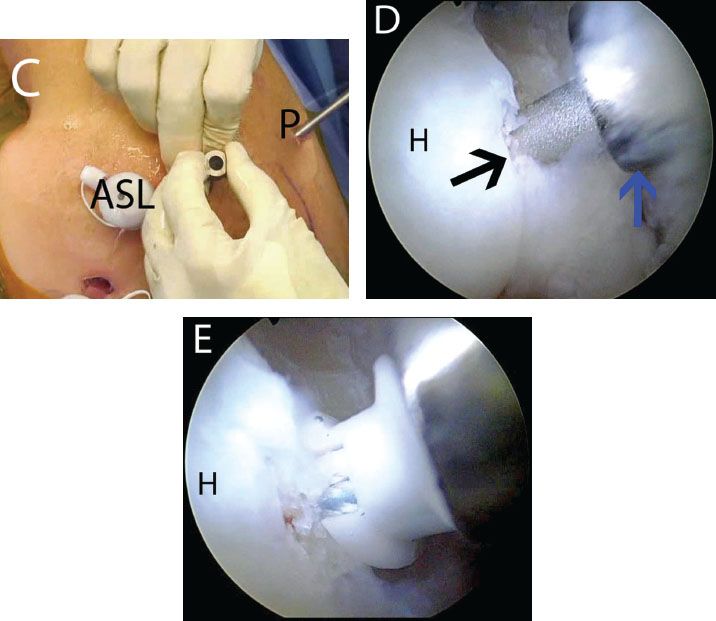

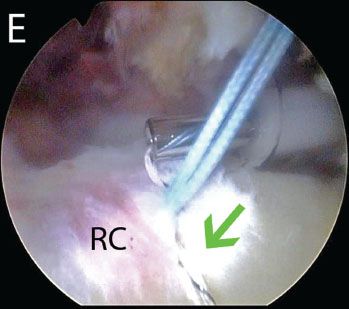

Figure 5.8 Using a metal cannula for transtendon anchor placement in a right shoulder. A: External view demonstrates a 5.0-mm metal cannula (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL). B: The cannula is inserted transtendon adjacent to a previously placed spinal needle. C: The inner trochar is removed for punch placement. D: Arthroscopic view from a posterior glenohumeral portal demonstrates punch placement (blackarrow) for creation of a bone socket. Note: The metal cannula (blue arrow) preserves the channel, simplifying bone socket creation and anchor placement. E: A 4.5-mm BioComposite Corkscrew FT anchor (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) is inserted. ASL, anterosuperolateral portal; H, humerus; P, posterior portal.

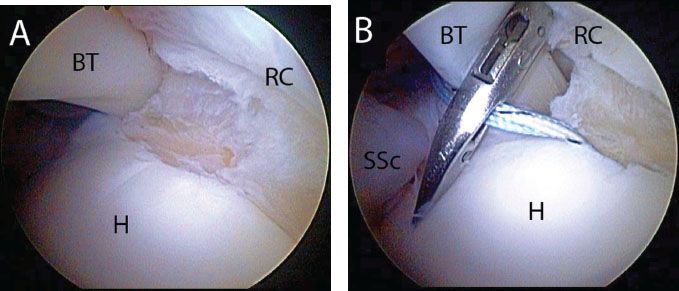

Figure 5.9 A: Right shoulder, posterior viewing portal, demonstrates a small articular-sided rotator cuff tear amenable to a single-anchor repair. B: After placement of a transtendon anchor, sutures can be passed retrograde with a Penetrator (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL). C: The sutures are passed to create a spread that will maximize footprint coverage. BT, biceps tendon; H, humerus; RC, rotator cuff; SSc, subscapularis tendon.

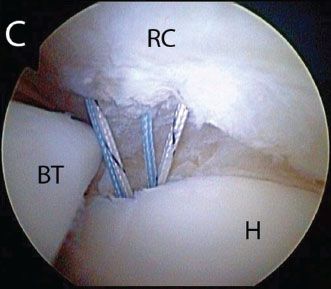

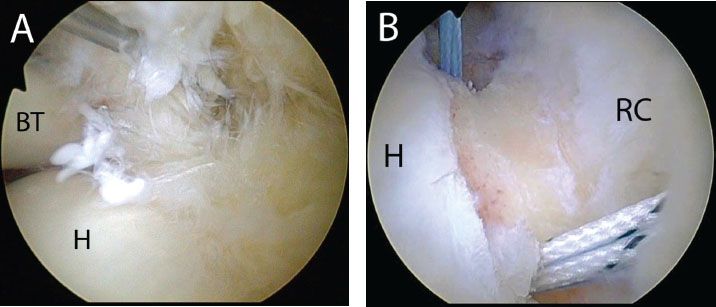

Figure 5.10 A: Right shoulder view from a posterior portal demonstrates a MicroLasso (blackarrow), which has been passed through the anterior rotator cuff to shuttle sutures for a PASTA.B: Sutures that have been individually passed to create a spread of sutures for a single-anchor repair of a PASTA. C: Subacromial view from a posterior portal in the same shoulder. BT, biceps tendon; H, humerus; RC, rotator cuff.

Figure 5.11 A: Right shoulder, posterior subacromial viewing portal, demonstrates final single-anchor repair of a PASTA. Note: The knots have been purposely tied to maximize the spread between contact points and thus maximize fixation. B: Intra-articular view from a posterior portal in the same shoulder demonstrates restoration of the medial footprint (Compare to Fig. 5.5B). BT, biceps tendon; H, humerus; RC, rotator cuff.

After passing sutures, the arthroscope is reintroduced into the subacromial space. The sutures are identified in the subacromial space and tied. To prevent “buckling” the tendon, the arm is brought into adduction and the sutures tied. The final construct should be viewed both on the bursal side and from the articular side to ensure tendon reduction to bone (Fig. 5.11).

Two Anchor Double-pulley Technique

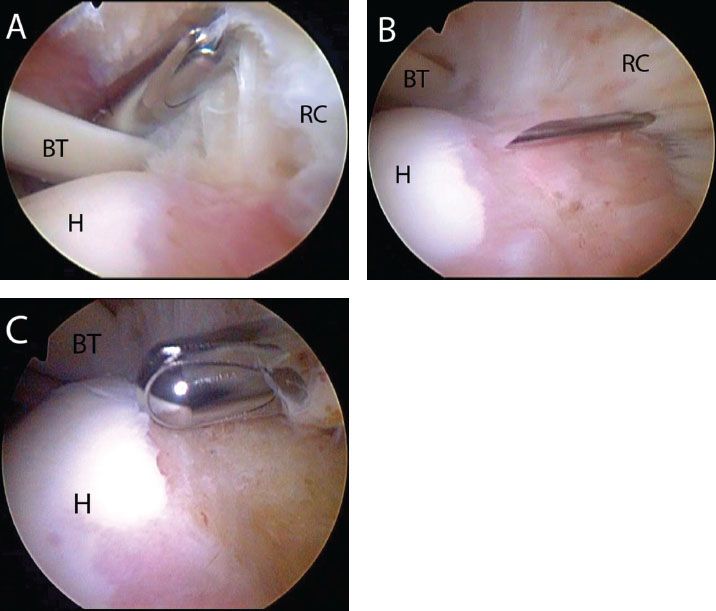

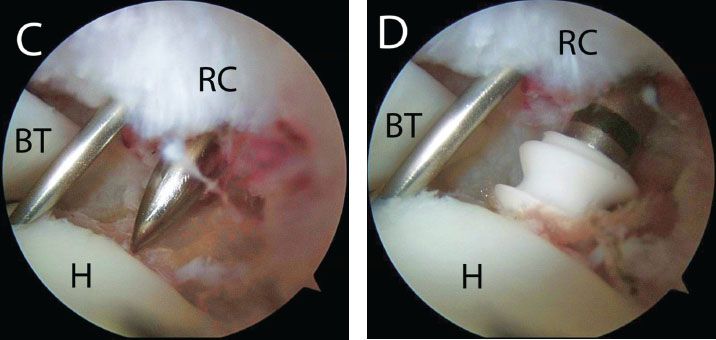

In patients with more extensive partial articular surface rotator cuff tears, two or more anchors may be required. Usually two anchors are required if >1.5 cm of the anterior-to-posterior footprint is involved. A subacromial bursectomy or decompression is performed prior to anchor insertion. In patients with extensive partial-thickness articular surface tears, two anchors are placed (e.g., BioComposite Corkscrew FT) transtendon as described previously, one anterior and one posterior in the medial aspect of the footprint (Fig. 5.12).

Figure 5.12 Right shoulder, posterior viewing portal. A: A partial-thickness rotator cuff tear is visualized. B: Anteromedial and posteromedial anchors have been placed in a transtendon fashion. BT, biceps tendon; H, humerus; RC, rotator cuff.

When using two or more anchors, the arthroscopist may choose to individually pass mattresses sutures as described previously. However, when two anchors are used, a “double-pulley” technique is possible. A suture from the anterior anchor may be tied to a suture from the posterior anchor to create a large mattress stitch between the anchors. One or both sutures pairs from each anchor may be used to create a mattress suture between the anchors.

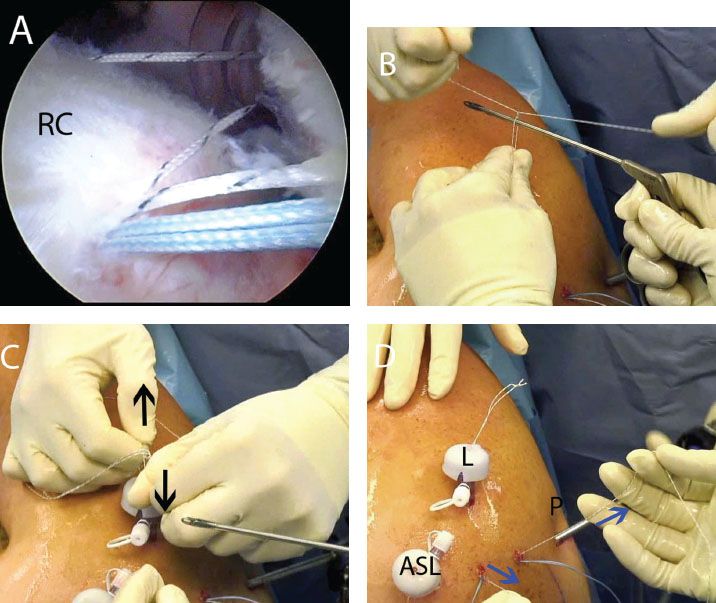

Following transtendon placement of two medial anchors, the arthroscope is reintroduced into the subacromial space and a cannula is established in the lateral portal. The suture limbs are then identified exiting the rotator cuff. To perform the double-pulley technique, one limb from each suture pair (i.e., one from the anterior anchor, one from the posterior anchor) is retrieved through the lateral cannula. A Surgeon’s knot is then tied extracorporeally and the tails cut. Using the anchor eyelets as pulleys, traction is applied to the opposite ends of the sutures, pulling the knot through the cannula, into the subacromial space and against the rotator cuff. The sutures are pulled until the knot lies taut against the rotator cuff. The opposite ends of the suture are then retrieved through the lateral portal and a static knot is tied using the Surgeon’s Sixth Finger (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL), closing the suture loop (Fig. 5.13). Because these latter sutures can no longer move between the anchor eyelets, a sliding knot is not possible and a static knot must be tied. This creates a double-mattress knot between anchors, the largest mattress loop possible, and compresses the rotator cuff along its entire anterior-to-posterior footprint. It also seals the medial margin of the footprint against synovial fluid (Fig. 5.14).

Figure 5.13 Double-pulley technique in a right shoulder. A: While viewing from a posterior subacromial portal, a suture from an anterior anchor and a suture from a posterior anchor are retrieved out a lateral portal. B: Extracorporeally, a surgeon’s knot is tied over an instrument. C: After the knot is tied, the surgeon pulls on the loop (blackarrows) to ensure that the knot does not slide. D: The suture tails at the knot are cut. Then, an assistant pulls on the opposite suture limbs (bluearrows) to deliver the knot into the subacromial space. E: The double-mattress knot is completed by tying the opposite suture limbs as a static knot with a Surgeon’s Sixth Finger Knot Pusher (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL). The first mattress knot is also seen (green arrow). ASL, anterosuperolateral portal; L, lateral subacromial portal; P, posterior portal; RC, rotator cuff.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree